- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Terrible Gifts

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Zoltan Torey’s Out of Darkness begins dramatically in Sydney. On a winter’s night in 1951, Torey, a refugee from Hungary studying dentistry, is on night shift at the battery factory in which he works to support his studies. When he moves a drum of acid, the plug blows off, ‘sending a massive jet of corrosive liquid at my face’. The acid eats into Torey’s eyes, blinding him for life. In addition, he swallows some acid, damaging his vocal cords. Torey describes this event twice: the second time, he emphasises how the event was experienced. ‘The last thing I saw with complete clarity was a glint of light in the flood of acid that was to engulf my face … It was a nano-second of sparkle, framed by the black circle of the drumface, less than a foot away.’ As this suggests, Torey’s prose has moments of extraordinary power.

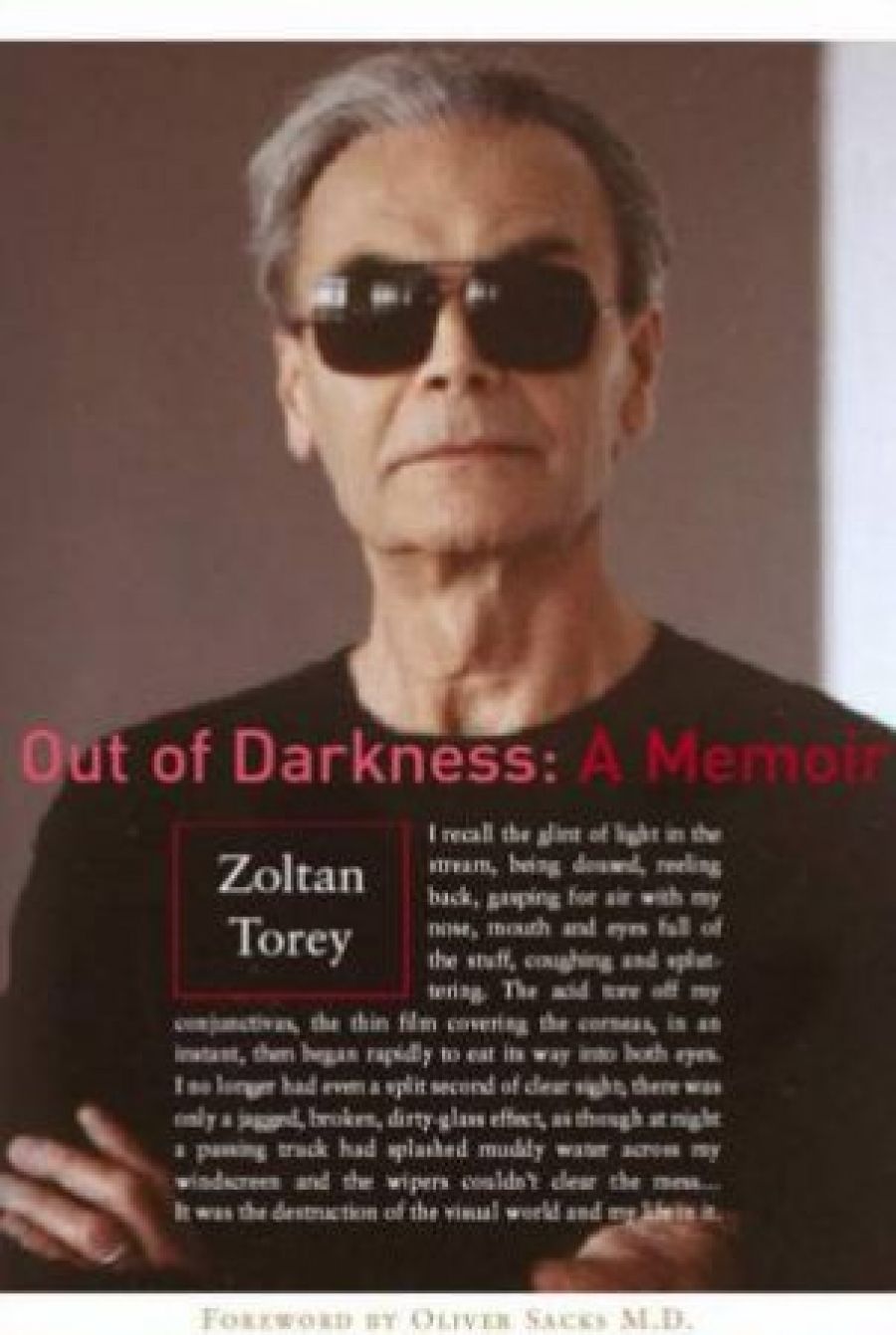

- Book 1 Title: Out of Darkness

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $30pb, 287pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

This glint of light framed by darkness is the beginning of a remarkable gift. Rejecting advice to the contrary, Torey begins to develop an intense mode of mental visualisation, to the point where he can write: ‘It is therefore hard for me to say that I am blind, if that means “not seeing things”.’ Oliver Sacks, in his enthusiastic and sensitively contextualising preface, quotes the French writer Jacques Lusseyran – ‘We are the visual blind’ – to give a sense of Torey’s condition. This condition, which uses, but does not succumb to, the brain’s ability to produce visual imagery when there is no sensory input, is perhaps the hardest thing for a sighted person to comprehend when reading Out of Darkness.

Not all blind people respond through visualisation. It is interesting to read Torey’s book in parallel with John M. Hull’s autobiography, Touching the Rock (1990), a book cited by both Torey and Sacks. Hull, unlike Torey, cannot visualise. Their different responses to travelling are indicative of the different conditions of their blindness. Hull’s work, based on taped diary entries, is more concerned than Torey’s with the immediacies of living with blindness, especially those to do with being a father. He stresses practical things, such as the difficulty when lost of getting helpful directions from sighted people, or his amused embarrassment on shaking the wrong man’s hand after a conference.

A blind man may mistake others, but, as Torey suggests, we are more likely to mistake him. I say ‘we’ with the arrogance of the sighted, assuming that, since I can see, then you, lecteur, can also see. Torey’s narrative is a minority report from a world the sighted share with the blind but cannot apprehend. This memoir reads as an account of blindness as much as a story of a Hungarian childhood, seeking refuge from the USSR, a career in psychology, his experience of fatherhood, and so on. But equally clear is Torey’s need not to make those other features of his life subsidiary to his blindness.

Other than his accident and its immediate aftermath, Torey is most vivid when describing his childhood, the war and his escape from Soviet Hungary. Indeed, this re-creation of a past world is one of the book’s greatest strengths, beginning with Torey’s first disconnected and lyrical memories: ‘A gateway to a shady garden, a large sandpit in the park, endless steps, windy paths to rocky heights.’ As this may suggest, things are comfortable: Torey’s father is the head of a large film studio. Such comfort, however, makes the family ‘class enemies’ under the Soviet régime.

Torey’s description of the siege of Buda and its aftermath is brief but memorable, bringing to mind other autobiographical descriptions of the war, such as Elena Jonaitis’s Elena’s Journey (1997), in which the simple rendering of events is powerful enough. In such contexts, even the simplest figure of speech can take on extraordinary resonance, as in Torey’s simile regarding the arrival of Soviet troops: ‘We civilians, like unwanted rats, lay low, trying to be inconspicuous and tolerated.’

Having survived the dangerous act of crossing the Iron Curtain, Torey begins to come to terms with Australia, studying, his injury and a precipitate marriage. The latter, which wasn’t a success, illustrates the ambiguity of Torey’s style. He is both open and reticent in his descriptions of relationships. This is a general feature of autobiography, but Torey makes it more apparent by explicitly raising problems that he cannot pursue. (A paragraph on his estranged son makes especially poignant reading).

The narrative impulse of Out of Darkness is to some extent disrupted by blindness, but Torey makes it clear that life went on. Gaining a university education and becoming a psychologist (not to mention fixing the guttering of his house) would seem achievements enough, but Torey’s autobiography has an endpoint, a ‘teleology’: the writing of his book on the problem of consciousness (published as The Crucible of Consciousness by OUP in 1999).

Out of Darkness has novelettish moments (‘this trim, grey-eyed brunette’), and descriptions of Torey’s youth are sometimes amusingly picaresque (assignations with older women; smuggling goods past Soviet authorities). Torey seems least convincing when describing his decision to ‘solve’ the problem of consciousness. At times, it can be a bit like Ripping Yarns: ‘My true interest, the investigation of the key to life and consciousness, seemed out of reach.’ While Torey has much to say about the pragmatic difficulties of writing such a book, his characterisation of the work itself comes down to one sentence. Perhaps we’re expected to read it for ourselves.

Torey is at his least self-effacing when discussing this book. Interestingly, his achievement here, while at the cutting edge of many disciplines, has a curiously classical cast. The ancients had much to say about blindness and the blind. Prophets, poets and visionaries were often characterised as blind. (‘Just Heav’n thee like Tiresias to requite / Rewards with Prophecy thy loss of sight’, as Andrew Marvell wrote about Milton). Such stuff must be hard to tolerate sometimes, but Torey strangely fits into this image. He is a seer, the one to discover the secret of consciousness, no less. And yet, Torey’s prophetic cast is grounded by a deep and enlightening pragmatism.

In a sense, Torey’s eyes were sacrificed. His injury could be read as another casualty of capitalism (a theme Torey shows no interest in pursuing). But, as with sacrifice in the religious sense, something is given back. Torey clearly doesn’t want to sentimentalise his injury, but he does argue that without it his life’s work would not have been accomplished or even conceived. What seemed to ruin Torey’s chances at work offered him new work, a secret work. Hull terms such an event a ‘terrible gift’.

The ‘secret’ world of the blind person is one that this autobiography goes to considerable efforts to make real to the sighted person. In this respect, an autobiography of a blind person is almost a paradigm for autobiography itself: a representation of a subjectivity that cannot be perceived, but must be narrated nevertheless. Torey’s book, then, is also a gift, and one that we should look at closely.

Comments powered by CComment