Ten years after the first ABR FAN Poll, the second one was limited to Australian novels published since 2000 (though we received votes for recent classics such as 1984, Voss, and Monkey Grip). When voting closed in mid-September, Richard Flanagan’s Booker Prize-winning novel The Narrow Road to the Deep North emerged as a clear winner. Ironically, Tim Winton’s Breath came fourth for the second time, ten years after it did so in the original FAN Poll for the best Australian novel of all time (which was won by Tim Winton's Cloudstreet). Alexis Wright’s Carpentaria and The Slap by Christos Tsiolkas were the only other crossover entries between the two lists.

After our Top Twenty feature we list all the individual novels as nominated by voters in alphabetical order. (Many more publications were nominated but these included short story collections, memoirs, non-fiction and international titles, as well as novels published before 2000, all of which were ineligible.)

Have your favourites made the list?

The Top Twenty

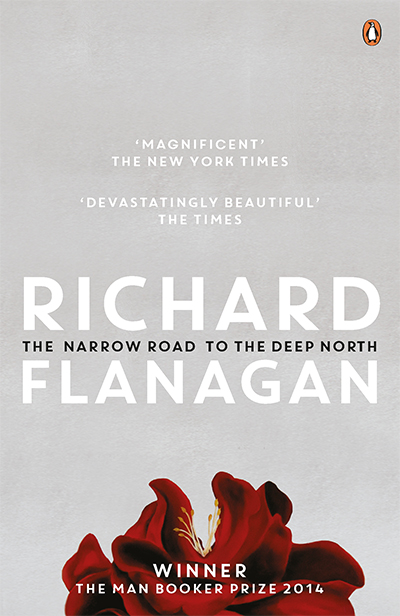

1. The Narrow Road to the Deep North

by Richard Flanagan (2013)

The Narrow Road to the Deep North, winner of the 2014 Man Booker Prize, is a dramatic wartime saga. With a deadly day on the Burma Railway at its heart, the tale begins in August 1943 with Dorrigo Evans, an Australian surgeon despairing in a Japanese POW camp. Evans, struggling to save himself and his fellow men from violence, disease, and death, can’t shake the memories of his love affair with his uncle’s young wife. The Narrow Road to the Deep North is a narrative reflecting the depravity of war but also the tentative nature of love.

Read Kerryn Goldsworthy's Reading Australia essay and James Ley's review.

2. Boy Swallows Universe

by Trent Dalton (2018)

Boy Swallows Universe, by Walkley Award-winning journalist and author Trent Dalton, has become a literary sensation. The first book ever to win four prizes at the Australian Book Industry awards, the novel is a funny, sensitive, and gripping coming-of-age tale set in 1980s Australia. Eli Bell and his mute brother, August, live in a housing estate on the fringes of Brisbane, and together they navigate the unpredictable world around them. ‘All of me is in here,’ Trent Dalton writes of his first novel. ‘Everything I’ve ever seen. Everything I’ve ever done.’

Read Trent Dalton's Open Page interview.

3. Carpentaria

by Alexis Wright (2006)

Carpentaria, by Waanyi writer Alexis Wright, is a sprawling narrative set in the small town of Desperance in the Gulf country of north-western Queensland. The tale, admired for its hybridised mix of myth, politics, and social commentary via an array of unforgettably unique characters, is a masterly piece of storytelling. It won the Australian Premier’s Literary Prize and the Miles Franklin Award in 2006, and has captured our imaginations ever since.

Read Kate McFadyen's review.

4. Breath

by Tim Winton (2008)

Breath by Tim Winton, winner of the 2009 Miles Franklin Award, follows paramedic Bruce Pike as he reflects on his youth. The story is set in Sawyer, a small Western Australian logging village near the fictional coastal town of Angelus, a place recurring in several of Winton's works. This deeply moving book of risk and friendship strikes a balance between the everyday and the extraordinary.

Read Tim Winton's Open Page interview and James Ley's review.

5. The Book Thief

by Markus Zusak (2005)

The Book Thief, set in Nazi Germany, follows Liesel, a young girl who finds a forgotten book, The Gravedigger’s Handbook, partially hidden in the snow.The theft of this abandoned book will alter the course of Liesel's life dramatically. Made into a major motion picture in 2013, The Book Thief was a bestseller from the start.

Read Lorien Kaye's review.

6. True History of the Kelly Gang

by Peter Carey (2000)

True History of the Kelly Gang, a virtuosic achievement, is Peter Carey’s vernacular riff on the Ned Kelly legend that won the 2001 Man Booker Prize. Ned Kelly, that renowned ‘black square with the ominous slit’, is indelibly ingrained into Australian lore. Depicted in innumerable books, films, and documentaries – and perhaps most vividly immortalised by Australian painter Sidney Nolan – Ned Kelly is a figure synonymous with Australian history. In True History of the Kelly Gang, novelist Peter Carey captures the man and myth in a classic outlaw tale: his own ode to the bushranger.

Read Peter Carey's Open Page interview and Morag Fraser's review.

7. The Museum of Modern Love

by Heather Rose (2016)

The Museum of Modern Love, Heather Rose’s mesmerising novel, follows Arky Levin, a film composer in New York separated from his wife. Arky one day finds himself at MOMA and sees Marina Abramovic in The Artist is Present, in which she had silent interactions with members of the public at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. As Arky watches the artwork unravel, so too does he.

Read Duncan Fardon's review.

8. The Natural Way of Things

by Charlotte Wood (2015)

The Natural Way of Things is a dark fable about misogyny and corporate control. It follows what happens after two women wake from a drugged sleep and find themselves imprisoned on a remote desert property, held prisoner with other women somewhere in the Australian bush by two male guards and a woman who claims to be a nurse.

Read Charlotte Wood's Open Page interview and Susan Lever's review.

9. The Slap

by Christos Tsiolkas (2008)

The Slap is a popular and provocative novel exploring societal and familial tensions through the fallout that follows a man slapping a child not his own at a suburban barbecue in Melbourne. Hugo, the slapped child, had been misbehaving while his parents failed to intervene. The slap sends everyone into a spiral, with some believing in physical discipline, while others think the police should be called.

Read Kerryn Goldsworthy's Reading Australia essay and James Ley's review.

10. Burial Rites

by Hannah Kent (2013)

Burial Rites, Hannah Kent's richly imagined début novel, explores the life of the last woman to be executed in Iceland, Agnes Magnúsdóttir. Iceland has no prisons, so Magnúsdóttir was held for the winter before her execution at a farm she'd lived at as a young girl. For this winter, she is guarded by the farmer's wife and daughters.

Read Bronwyn Lea's review.

The remaining titles in the top twenty:

11. Jasper Jones by Craig Silvey (2009)

Read Andrew Nette's review of the film adaptation

12. Questions of Travel by Michelle de Kretser (2012)

Read Michelle de Kretser's Open Page interview and Melinda Harvey's review

13. The Dry by Jane Harper (2016)

Read Chris Flynn's review

14. The Secret River by Kate Grenville (2005)

Read Kate Grenville's Open Page interview and Kerryn Goldsworthy's review

15. Ransom by David Malouf (2009)

Read Peter Rose's review

16. Truth by Peter Temple (2008)

Read Chris Womersley's review

17. A Fraction of the Whole by Steve Toltz (2008)

Read Louise Swinn's review

18. Foal’s Bread by Gillian Mears (2011)

Read Gillian Mears's Open Page interview and Gillian Dooley's review

19. That Deadman Dance by Kim Scott (2010)

Read Patrick Allington's Reading Australia essay and review

20. The Great Fire by Shirley Hazzard (2003)

Read Brenda Niall's review

2019 ABR FAN Poll results

Below is a listing of all the eligible novels nominated for the ABR FAN Poll by ABR readers. Are your favourites among them?

A

Michael Mohammed Ahmad: The Lebs (2018)

Belinda Alexandra: Tuscan Rose (2010)

Louise Allan: The Sisters’ Song (2018)

Steven Amsterdam: The Easy Way Out (2016)

Steven Amsterdam: Things We Didn’t See Coming (2009)

Charlie Archbold: Mallee Boys (2017)

Robbie Arnott: Flames (2018)

Melissa Ashley: The Birdman’s Wife (2016)

B

Murray Bail: The Voyage (2012)

Peter Barry: I Hate Martin Amis Et Al (2011)

Tony Birch: Blood (2011)

Tony Birch: The White Girl (2019)

Tony Birch: Ghost River (2015)

Stephanie Bishop: The Other Side of the World (2015)

Emily Bitto: The Strays (2014)

Georgia Blain: Between a Wolf and a Dog (2016)

James Bradley: Clade (2015)

Mark Brandi: Wimmera (2017)

Mark Brandi: The Rip (2017)

Geraldine Brooks: Year of Wonders (2001)

Geraldine Brooks: March (2005)

Geraldine Brooks: People of the Book (2008)

C

Peter Carey: True History of the Kelly Gang (2000)

Peter Carey: A Long Way From Home (2017)

Peter Carey: Theft: A Love Story (2006)

Steven Carroll: The Art of the Engine Driver (2001)

Steven Carroll: The Time We Have Taken (2007)

Brian Castro: Shanghai Dancing (2003)

Melanie Cheng: Room For a Stranger (2019)

Rebekah Clarkson: Barking Dogs (2017)

J.M. Coetzee: Elizabeth Costello (2003)

J.M. Coetzee: Summertime (2009)

Claire G. Coleman: Terra Nullius (2017)

Matthew Condon: The Trout Opera (2018)

Peter Corris: Salt and Blood (2002)

Moya Costello: Harriet Chandler (2014)

Jack Cox: Dodge Rose (2016)

Amanda Curtin: Elemental (2013)

D

John Dale: Detective Work (2015)

Trent Dalton: Boy Swallows Universe (2018)

Lea Davey: Silkworm Secrets (2016)

Luke Davies: Isabelle the Navigator (2000)

Michelle de Kretser: Questions of Travel (2012)

Michelle de Kretser: The Hamilton Case (2003)

Michelle de Kretser: The Life to Come (2017)

Garry Disher: Her (2017)

Garry Disher: Bitter Wash Road (2013)

Ceridwen Dovey: In the Garden of the Fugitives (2018)

Jennifer Down: Our Magic Hour (2016)

Sara Dowse: As the Lonely Fly (2017)

Robert Drewe: Whipbird (2017)

Robert Drewe: Grace (2005)

F

Richard Flanagan: The Narrow Road to the Deep North (2013)

Richard Flanagan: Gould’s Book of Fish (2001)

Richard Flanagan: Wanting (2008)

Penny Flanagan: Surviving Hal (2018)

Kate Forsyth: The Wild Girl (2013)

Kate Forsyth: Bitter Greens (2012)

David Foster: Sons of the Rumour (2009)

Karen Foxlee: Lenny’s Book of Everything (2018)

Jackie French: Pennies for Hitler (2012)

Peggy Frew: Hope Farm (2015)

Anna Funder: All That I Am (2011)

G

Enza Gandolfo: The Bridge (2018)

Helen Garner: The Spare Room (2009)

Sulari Gentill: Crossing the Lines (2017)

Scott G. Gibson: Making Tracks (2016)

Alicia Gilmore: Path to the Night Sea (2018)

Dennis Glover: The Last Man in Europe (2017)

Andrea Goldsmith: Invented Lives (2019)

Andrea Goldsmith: The Memory Trap (2013)

Peter Goldsworthy: Three Dog Night (2003)

Kate Grenville: The Secret River (2005)

Kate Grenville: Sarah Thornhill (2011)

H

Eleni Hale: Stone Girl (2018)

Leanne Hall: This Is Shyness (2010)

Rosalie Ham: The Dressmaker (2000)

Chris Hammer: Scrublands (2018)

Jane Harper: The Dry (2016)

Jane Harper: The Lost Man (2018)

Elizabeth Harrower: In Certain Circles (2014)

Sonya Hartnett: Of A Boy (2002)

Ashley Hay: The Body in the Clouds (2010)

Shirley Hazzard: The Great Fire (2003)

Robert Hillman: The Bookshop of the Broken Hearted (2018)

Lia Hills: The Crying Place (2017)

Chloe Hooper: The Engagement (2012)

Eva Hornung: Dog Boy (2009)

Paul Howarth: Only Killers and Thieves (2018)

I

Lisa Ireland: The Shape of Us (2017)

Stephen M. Irwin: The Dead Path (2009)

J

Kate Jennings: Moral Hazard (2002)

Frances Johnson: Eugene’s Falls (2007)

Gail Jones: Five Bells (2011)

Gail Jones: Dreams of Speaking (2006)

Gail Jones: Sixty Lights (2004)

Gail Jones: Sorry (2007)

Toni Jordan: Nine Days (2012)

Toni Jordan: Our Tiny, Useless Hearts (2016)

Toni Jordan: The Fragments (2018)

Mireille Juchau: The World Without Us (2015)

K

Leah Kaminsky: The Hollow Bones (2019)

Cate Kennedy: The World Beneath (2009)

Hannah Kent: Burial Rites (2013)

Krissy Kneen: An Uncertain Grace (2017)

Jay Kristoff: Nevernight (2016)

Ambelin Kwaymullina and Ezekiel Kwaymullina: Catching Teller Crow (2018)

L

Sofie Laguna: The Eye of the Sheep (2014)

Sofie Laguna: The Choke (2017)

Margo Lanagan: Sea Hearts (2012)

Eleanor Limprecht: The Passengers (2018)

Joshua Lobb: The Flight of Birds (2019)

Joan London: The Golden Age (2018)

Joan London: The Good Parents (2008)

Melissa Lucashenko: Too Much Lip (2018)

Melissa Lucashenko: Mullumbimby (2013)

M

Emily Maguire: An Isolated Incident (2016)

David Malouf: Ransom (2009)

Melina Marchetta: The Piper’s Son (2010)

Melina Marchetta: On the Jellicoe Road (2006)

Melina Marchetta: Saving Francesca (2003)

Juliet Marillier: Den of Wolves (2017)

Fiona McFarlane: The Night Guest (2014)

Andrew McGahan: The White Earth (2004)

Andrew McGahan: Last Drinks (2000)

Fiona McGregor: Indelible Ink (2010)

Catherine McKinnon: Storyland (2017)

Dervla McTiernan: The Ruin (2018)

Dervla McTiernan: The Scholar (2019)

Gillian Mears: Foal’s Bread (2011)

Kate Mildenhall: Skylarking (2016)

Alex Miller: Journey to the Stone Country (2002)

Alex Miller: Coal Creek (2013)

Alex Miller: The Passage of Love (2016)

Alex Miller: Autumn Laing (2011)

Jennifer Mills: Dyschronia (2018)

Frank Moorhouse: Cold Light (2011)

Frank Moorhouse: Dark Palace (2000)

Liane Moriarty: Big Little Lies (2014)

Cass Moriarty: The Promise Seed (2015)

Jaclyn Moriarty: The Slightly Alarming Tale of the Whispering Wars (2018)

Zoe Morrison: Music and Freedom (2016)

Kate Morton: The Forgotten Garden (2008)

Gerald Murnane: Border Districts (2017)

Gerald Murnane: Barley Patch (2009)

Gerald Murnane: A Million Windows (2014)

Gerald Murnane: A Season on Earth (2019)

Lois Murphy: Soon (2017)

O

Ryan O’Neal: Their Brilliant Careers (2016)

Stephen Orr: The Hands (2016)

Stephen Orr: This Excellent Machine (2019)

Wendy Orr: Dragonfly Song (2016)

P

Favel Parrett: Past the Shallows (2011)

Favel Parrett: When the Night Comes (2014)

Elliot Perlman: Seven Types of Ambiguity (2005)

Elliot Perlman: The Street Sweeper (2011)

Marcella Polain: Driving into the Sun (2019)

John Purcell: The Girl on the Page (2018)

R

Christopher Raja: The Burning Elephant (2015)

Jane Rawson: From the Wreck (2017)

Jane Rawson: A Wrong Turn at the Office of Unmade Lists (2013)

Matthew Reilly: Seven Ancient Wonders (2005)

Kelly Rimmer: The Things We Cannot Say (2019)

Holly Ringland: The Lost Flowers of Alice Hart (2018)

Michael Robotham: Life or Death (2014)

Michael Robotham: Good Girl, Bad Girl (2019)

Heather Rose: The Museum of Modern Love (2016)

Peter Rose: Roddy Parr (2010)

Heather Rose: The Butterfly Man (2005)

Sarah Ross-Simon: The Woman of Maldon (2017)

Josephine Rowe: A Loving, Faithful Animal (2016)

S

Michael Sala: The Restorer (2017)

Eva Sallis: Fire Fire (2004)

Sarah Schmidt: See What I Have Done (2017)

Kim Scott: That Deadman Dance (2010)

John A. Scott: N (2014)

Kim Scott: Taboo (2017)

Jock Serong: On the Java Ridge (2017)

Jock Serong: Preservation (2018)

Jessica Shirvington: Empowered (2013)

Craig Silvey: Jasper Jones (2009)

Craig Silvey: Rhubarb (2004)

Inga Simpson: Mr Wigg (2013)

Graeme Simsion: The Rosie Project (2013)

Alex Skovron: The Poet (2005)

Tim Slee: Taking Tom Murray Home (2019)

Pip Smith: Half Wild (2017)

Tracey Sorensen: The Lucky Galah (2018)

Anna Spargo-Ryan: The Paper House (2016)

M.L. Stedman: The Light Between Oceans (2012)

Laurie Steed: You Belong Here (2018)

T

Cory Taylor: Me and Mr Booker (2011)

Peter Temple: Truth (2008)

Peter Temple: The Broken Shore (2005)

Carrie Tiffany: Mateship with Birds (2012)

Carrie Tiffany: Everyman’s Rules for Scientific Living (2005)

Carrie Tiffany: Exploded View (2019)

Steve Toltz: A Fraction of the Whole (2008)

Jessica Townsend: Nevermoor: The trials of Morrigan Crow (2017)

Lucy Treloar: Salt Creek (2017)

Christos Tsiolkas: Barracuda (2014)

Christos Tsiolkas: Dead Europe (2005)

Christos Tsiolkas: The Slap (2008)

V

Joanne van Os: Ronan’s Echo (2014)

Karen Viggers: The Orchardist’s Daughter (2019)

W

Josephine Wilson: Extinctions (2016)

Rohan Wilson: The Roving Party (2011)

Tara June Winch: Swallow the Air (2003)

Tim Winton: Breath (2008)

Tim Winton: Dirt Music (2001)

Tim Winton: The Shepherd’s Hut (2018)

Tim Winton: Eyrie (2013)

Chris Womersley: Bereft (2010)

Charlotte Wood: The Natural Way of Things (2015)

Charlotte Wood: Animal People (2011)

Charlotte Wood: The Submerged Cathedral (2004)

Laura Elizabeth Woollett: Beautiful Revolutionary (2018)

Alexis Wright: Carpentaria (2006)

Alexis Wright: The Swan Book (2013)

Evie Wyld: All the Birds, Singing (2013)

Z

Arnold Zable: Sea of Many Returns (2008)

Claire Zorn: The Sky So Heavy (2013)

Markus Zusak: The Book Thief (2005)

Markus Zusak: Bridge of Clay (2018)

Markus Zusak: The Messenger (2002)