- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Grid Image): Act of Grace

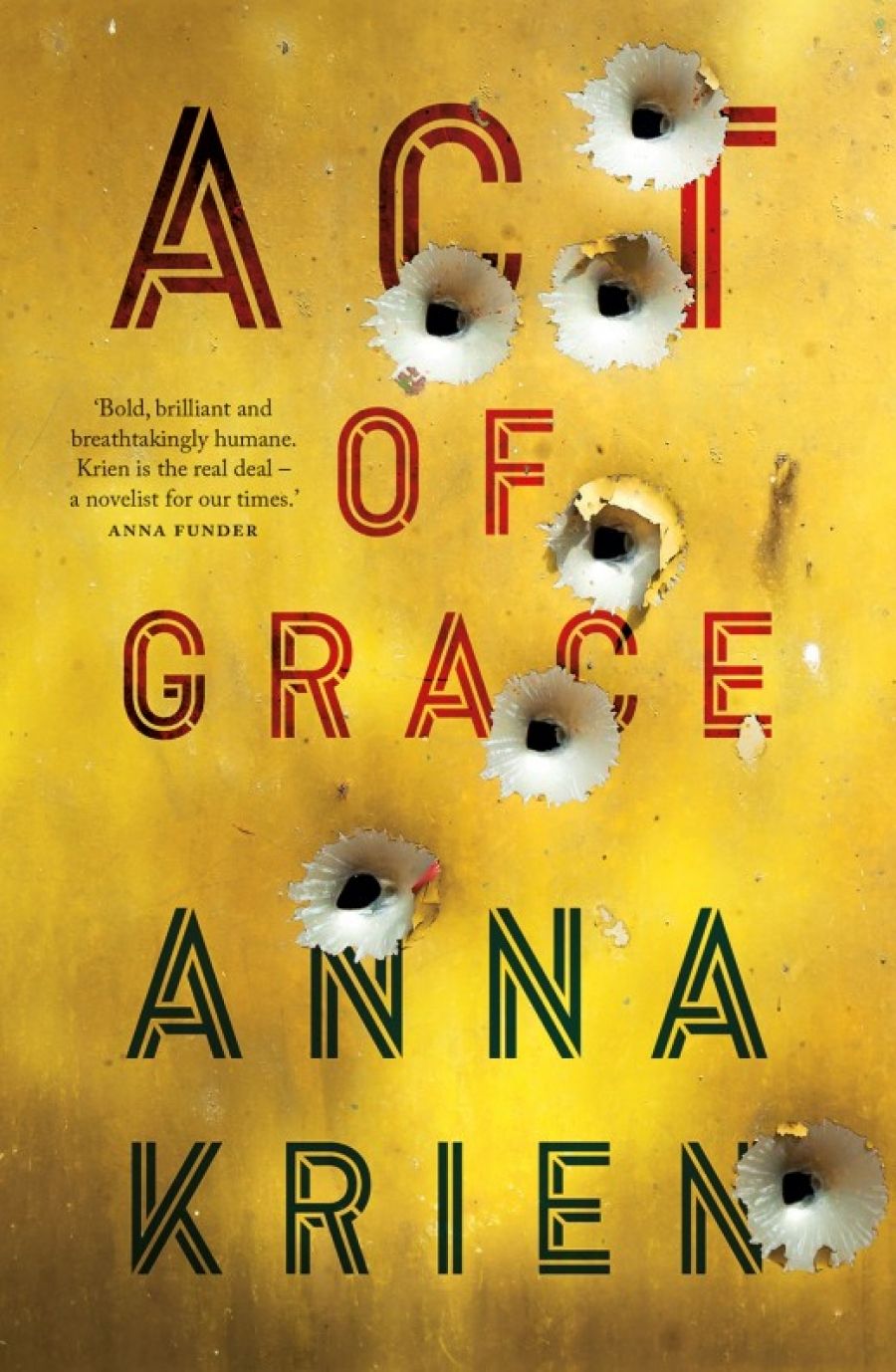

- Book 1 Title: Act of Grace

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $32.99 pb, 336 pp, 9781863959551

Act of Grace opens with an embittered Iraqi veteran returned to his uneasy family in Australia, shards of shrapnel from a suicide-bombing attack embedded in his neck. This ‘scattering of lumps that seemed to shape-shift every few days’ is a visible marker of damage, but the internal disfiguring that Toohey Colpitt has experienced is far more sinister and pervasive. In Iraq, the triumphant idealism of the Australian soldiers, who view themselves as saviours and bask in ‘the glow of aid’ as they dispense candies and footballs emblazoned with the Australian flag, is soon shattered by the mounting resentment of the Iraqis. Children, malnourished due to punitive sanctions, begin to shout insults at the soldiers on their missions of mercy, and eventually throw rocks at the men. Any symbolic freight the stones tossed by tiny Davids at conquering Goliaths might have is subverted when the soldiers respond in kind, holding competitions to see who can inflict the most damage, the Iraqi children ‘targets more real than the shadowy enemy’.

From here we are catapulted into the lives of the O’Farrell family in Melbourne. Danny who describes himself as ‘Half-Aborigine’, has a complicated and uneasy relationship with his heritage. He rails against the naïve romanticisation of his Aboriginality and hides his secret terror that his children will be taken from him in the way he was from his mother. Danny delights in the fact that his son is fair-skinned and blue-eyed, that ‘his kin would get through the system unimpeded’, while he instructs his daughter Robbie, with her dark features, to tell people that she is Italian and views her with ‘a sinking feeling, an unshakeable sadness, a miserly sense of history repeating’.

The novel’s sweep gradually expands to include a vast circle of characters and experiences. Disparate and seemingly disconnected sets of public and private narratives circle around each other, with unexpected moments of cross-pollination. At first Act of Grace seems to be a set of discrete stories, albeit with intersecting themes and repeated motifs, but soon the different narratives weave together in sometimes startling ways. The connections never feel contrived or clumsy; they are entirely believable in a novel preoccupied with the coincidences and contingencies of history, with the echoes and repetitions of the past.

Anna Krien (photograph via Black Inc.)

Anna Krien (photograph via Black Inc.)

The danger of such a complex and multi-peopled canvas is that the experiences of any one individual risk being submerged in the flow of time and the calamitous course of global history. In Krien’s assured hands, the narratives take on a powerful parallactic effect and the accretion of experiences serves to enlarge rather than diminish the story she is trying to tell. Uncannily at home in all of the lives she inhabits, Krien’s exploration of moral complications is exactingly realistic, her narrative command astounding, and her prose precise and lyrical.

In the novel’s final paragraphs, Melbourne comes to a standstill as three Aboriginal flags are raised from the West Gate Bridge. The tattered Australian flags are taken down and the colours of the Aboriginal flags unfurl against the skyline as television crews record the occasion and police flank the highway. For Robbie, this is a triumphant act, a personal and national moment of reckoning, of reclamation. Iraqi exile Nasim, irretrievably unmoored from her own land and history, cannot understand what she sees as an inexplicable preoccupation with ownership: ‘It was beyond her, this obsession of Robbie’s about whose country this was. Small-minded, too, for surely it was a mere cigarette paper of sediment in the history of the earth. “All countries are the inheritance of murderers,” she had said once to Robbie.’

The storehouse of history may be a ruinous depository and victories may be contingent and complicated, but for all the novel’s bleak intelligence, it never plunges the reader into permanent despair. The purpose of art, Auden wrote, in the context of historical cataclysm, ‘is to show an affirming flame’. Krien does not offer any easy redemption and the novel’s register is frequently melancholic, but there are enlivening moments of relief and restitution. A burial, a homecoming, the birth of a child, lives reassembled and calamities endured: there are acts of grace large and small threaded throughout the sweep of the novel. The affirming flame may leap and flicker, may burn so low as to barely be seen, but it is never extinguished.

Comments powered by CComment