- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text: It is commonly accepted that the modern European novel begins with Don Quixote. Lionel Trilling went so far as to claim that the entire history of the modern novel could be interpreted as variations on themes set out in Cervantes’s great originating work. And the quality that is usually taken to mark Don Quixote as ...

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): The Death of Jesus

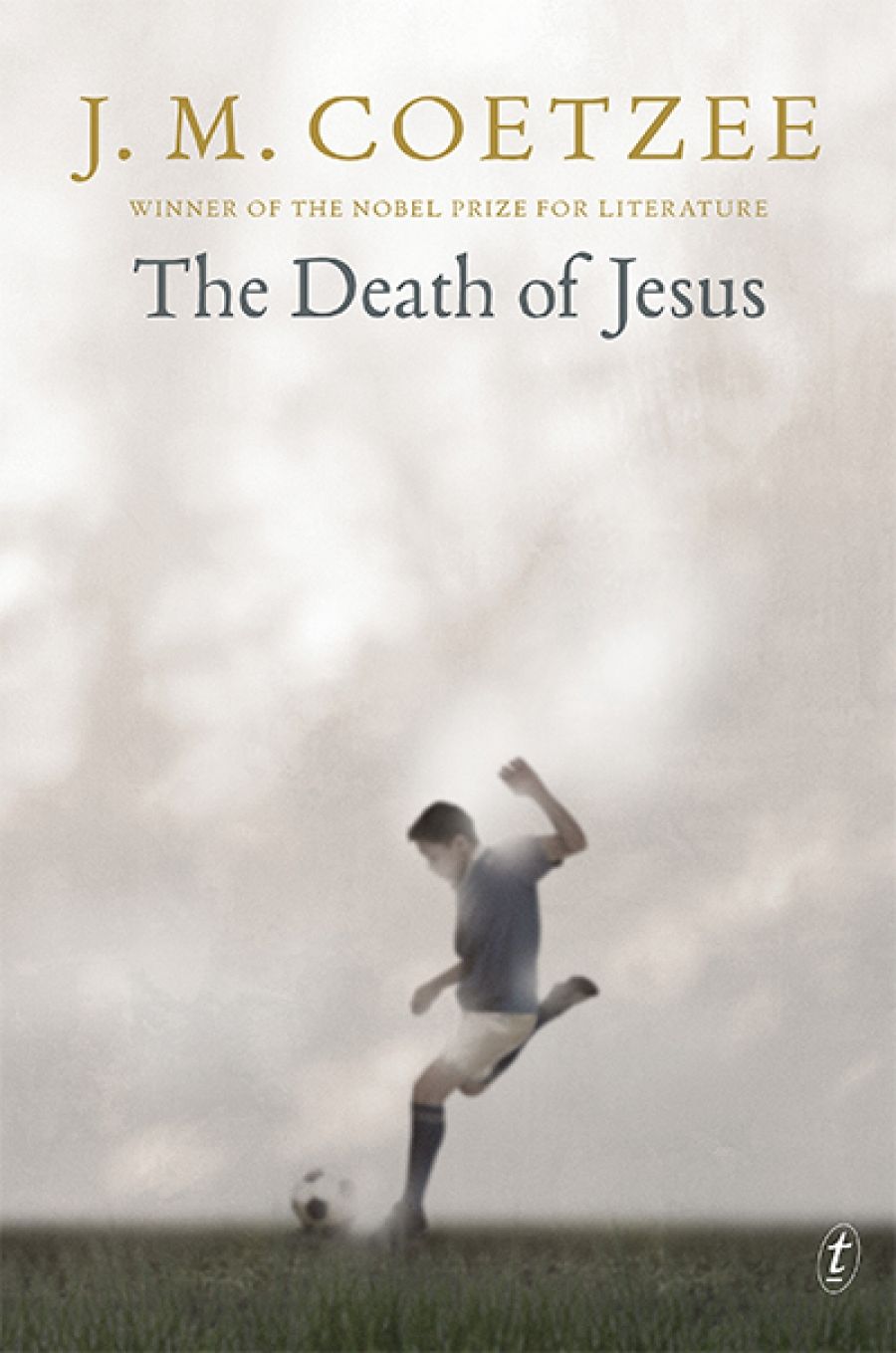

- Book 1 Title: The Death of Jesus

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $29.99 hb, 197 pp, 9781922268280

Simón’s reading is questionable at best and subject to its own contextual ironies, not the least of which is that he is himself a character in a made-up story set in an unreal world. As Coetzee has noted elsewhere (echoing, inadvertently it would seem, another observation by Trilling), the proposition that there is a sharp line to be drawn between reality and fantasy is one of the things Don Quixote calls into question. Its ‘message’ is more or less antithetical to that suggested by Simón. What Quixote’s delusions eventually demonstrate is that the distinction between the real and the ideal is not absolute, that reality is not necessarily fixed and unyielding. His decision to live according to his ideals does indeed alter the world for the better. The satirical implications of the novel are thus reversed: Quixote’s madness becomes a comment on the wretchedness of reality. This was the interpretation favoured by Dostoevsky, who maintained that Don Quixote was the pre-eminent example of a genuinely virtuous character, but the corruption of the world meant that his essential goodness appeared to be simultaneously absurd. It is his misfortune, Quixote informs Sancho, to have been born into an ‘age of iron’ – which is also to say, an age of irony that regards an allegiance to any kind of higher principle as something deserving of ridicule and scorn, an age that treats idealism as a form of insanity.

Coetzee’s novels have always inhabited other fictions and displayed an element of self-consciousness about their status as fictions. Even Disgrace (1999), the most conventionally ‘realist’ of his novels, carries a weight of concentrated symbolism and allegorical implication that is constantly overwhelming the specificity of its narrative. This characteristic sense of doubleness assumes a striking form in Coetzee’s Jesus trilogy. Viewed as the culmination (if not necessarily the conclusion) of his long literary career, these distinctive late fictions achieve a remarkable synthesis of the influences, styles, and thematic preoccupations that have animated his work for the better part of half a century.

‘Late style,’ wrote Edward Said, ‘is what happens if art does not abdicate its rights in favour of reality.’ In Coetzee’s case, his enduring allegiance to his art has come to foreground the extent to which he regards its formal and moral dimensions as inextricable. The Jesus novels can be read as, among other things, reflections on the ontological status of fiction. They consider what it might mean to live one’s life in the service of the imagination. The moral dimension of this question is implied in their provocative conflation of Jesus and Quixote. Is it not the case that to believe in the former’s promise of redemption is to be as deluded as the latter?

J.M. Coetzee (photograph via the Nobel Prize)

J.M. Coetzee (photograph via the Nobel Prize)

The Death of Jesus brings the trilogy to a close, without going so far as to provide any definitive answers to the philosophical questions it raises. It begins several years after the conclusion of the second novel in the series, The Schooldays of Jesus (2016). David is now ten. His philosophical disagreements with Simón are becoming increasingly heated; there is a new note of existential angst in his questioning. He still loves Don Quixote, which he treats ‘not as a made-up story but as a veritable history’. He also loves playing soccer. When Señor Fabricante, who runs the local orphanage, invites David to come and live at the orphanage and play in an organised competition, David accepts the offer. Señor Arroyo, head of the unconventional Academy where David attends school, explains to the dismayed Simón that David ‘feels a certain duty toward Fabricante’s orphans, toward orphans in general, the world’s orphans’.

Soon after relocating, David is stricken with a mysterious ‘falling’ illness. There is a period of hospitalisation, during which he begins reciting tales from Don Quixote to gatherings of enraptured children. The disreputable Dmitri, convicted of a crime of passion in Schooldays, reappears on the scene, insisting that he is rehabilitated. He insinuates himself into David’s confidence and begins claiming that he has been entrusted with the true meaning of the boy’s unique vision. Then David’s condition deteriorates and he dies, after a series of anguished conversations with Simón about death, the ‘pain and contortion’ of his body ‘giving expression to the dilemma he confronted’. The latter stages of the novel are given over the grief and confusion of those who knew him, each of whom seems to have a different opinion about the meaning of his life. ‘Everyone is convinced that David had a message for us,’ observes Simón, ‘but no one knows what the message is.’

As this brief outline perhaps suggests, David is Jesus in much the same way that Leopold Bloom is Ulysses. The parallelism is loose and intrinsically ironic, but it is not intended as a form of mockery. Joyce wants us to recognise an element of genuine heroism in Bloom’s ordinariness and decency; Coetzee, similarly, wants us to give serious consideration to the idea that David is special – it is the one thing everyone seems to agree upon.

In presenting us with such an attenuated life, Coetzee grants David the cover of childhood innocence, thus protecting him from the charge of absurdity. He also strips his quasi-religious tale back to its essence. The Jesus novels propose a familiar quixotic inversion: David’s mysticism and suspicion of reason are presented as challenges to the stolid realism of Simón, who lives ‘in the present like an ox’. His peculiarity is used to suggest that when we seek to quantify and explain we are subjecting ourselves to constraining narratives, denying other realities. The trilogy offers no solution to this basic dilemma, though its sympathies with David’s rejection of instrumentalist reasoning are clear enough. Like all of Coetzee’s fiction, it stages a debate in which characters represent different views but can also be seen to contradict themselves and echo one another (the passionate Dmitri also likens himself to an ox in Schooldays, for example). The simplicity and directness with which the trilogy raises fundamental questions – and questions don’t come much more fundamental than ‘why are we here?’ – are matched by the intricacy with which they are dramatised. Coetzee’s scrupulous uncertainty, his remarkable ability to write fiction that seems to be at once confessional and self-effacing, has in the past been criticised for its evasiveness, but the Jesus novels leave little doubt that this tendency is better interpreted as expressive.

There is a small example of Coetzee’s mastery of a certain kind of self-effacing irony late in The Death of Jesus when he has Dmitri, whose name is important, assert that names are unimportant. This is arguably true in reality (though who’s to say our lives are not influenced by what we are called), but it is certainly not true in a novel in which every detail must be counted as significant and even implied absences can be meaningful. When I reviewed The Schooldays of Jesus for another publication back in 2016, I noted that the characters Dmitri and Alyosha were clear allusions to Dostoevsky’s final masterpiece, The Brothers Karamazov. I also noted that there was no character named after Ivan, the middle Karamazov brother, who voices the novel’s most searching existential questions. I was wrong, of course. It was when I read Dmitri’s disavowal that the penny dropped. There is no character named Ivan, but he is everywhere in Coetzee’s Jesus novels. In a sense, he is their author. Ivan is, after all, the Russian equivalent of John.

Comments powered by CComment