- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Grid Image): The Breeding Season

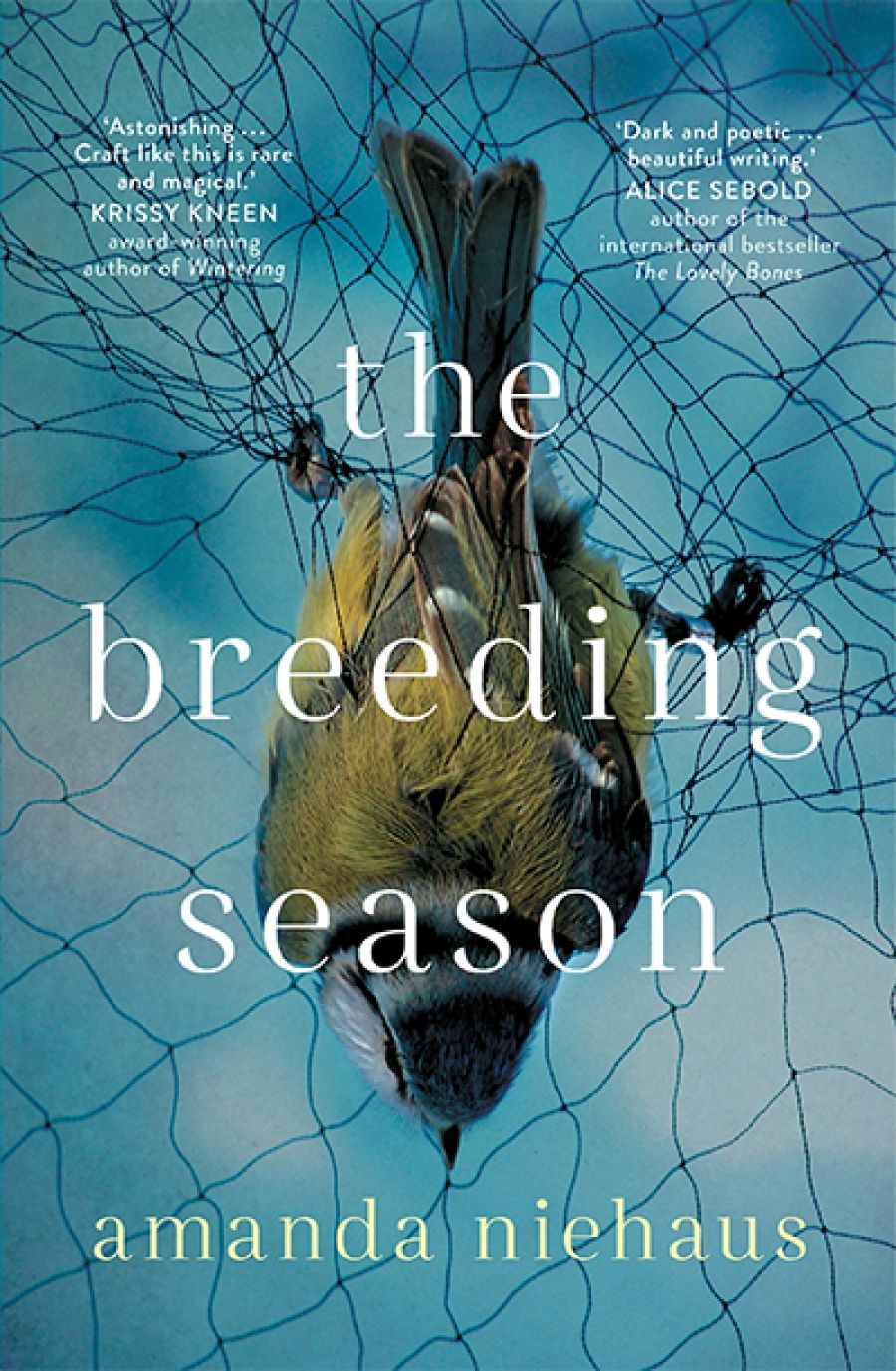

- Book 1 Title: The Breeding Season

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.99 pb, 272 pp, 9781760529536

Sex and death are constantly aligned thus in The Breeding Season. Much of Elise’s work focuses on the antechinus, a native marsupial mouse; antechinuses, Niehaus writes, ‘give so much to breeding that they die’ each generation, the males immediately after mating and the females after the young are weaned. Dan’s artist uncle, meanwhile, is best known for a work that depicts Hannah Wallace’s vulva, but also shows other projects featuring ‘skin that seems to crumble away into … dust or ash’ and ‘human-unhuman’ bodies. Accordingly, Elise and Dan are also positioned as both opposite and intertwined. As well as being a scientist and a writer, respectively, and approaching similar subjects with their different mindsets and practices, they are taken at one point to ‘the opposite poles of Australia’ by their work: Elise to Groote Eylandt in the Gulf of Carpentaria, and Dan to Hobart and the Museum of Old and New Art. This positioning is, of course, useful to the development of the ideas at the heart of the novel, but it also feels heavy-handed at times: the characters have a tendency to act more like metaphors than people.

Niehaus is also interested in what she terms ‘writing through [the] body’, and this accounts for the distinctive style of the book. At moments of great emotion or crisis, or of sudden bodily response to the external world, Niehaus breaks up the prose into short lines, in order to register a particular kind of physical shock or the sense of slowed time that is often experienced in these moments. When Dan first speaks to Hannah on the phone, for example, her laugh is described as:

a deep, throaty sound that reverberates through his phone

jaw

tongue

Elsewhere, usually at moments of gentleness or wonder, Niehaus runs words together. When Elise remembers her early fieldwork, for example, she describes the sandpiper hatchlings she worked with as ‘dappledowned and cottonball soft’, their fledging as ‘dash[ing] onetwothreefour out of their nests’.

These are, of course, techniques borrowed from poetry. Used adeptly, they add an element of lyricism to the writing, and the way in which they intensify narrative time is interesting and visceral. But they aren’t used sparingly enough to be consistently effective, and they begin to grate as the novel progresses. This kind of bodily writing also has a tendency to feel excessive in some of Niehaus’s depictions of sex and sexuality – early on, for example, Dan returns home from a furious, grief-fuelled jog, and imagines a woman (it’s unclear whether this is his wife or Hannah) while he is in the shower:

Pulse beats beats beats … He lets a body-not-body enter his mind, settle onto him, lavender-scented, and he pushes against her, warmwet and pressing … She wraps her strong legs around him, clampsuck vagina, and then she is off …

Niehaus is aiming for a directness and immediacy that bypasses language, that is experiential, rather than intellectual. It is especially gratifying to see this kind of risk-taking in a début work, even if it sometimes feels belaboured or pulls the reader away from the text.

This emphasis on writing through the body is also an attempt to circumvent writing about the body as an object, a thing that is looked at and observed rather than lived. This concern with gaze is also a part of both Dan’s and Elise’s work. Dan describes his uncle’s work to a creative writing workshop as ‘art made of bodies and on them, shapes of the body’, and proceeds to be undone by the students – all women – who question both the ethics of this work and the fact that Dan has only brought along, as stimulus material, pictures of women. Elise, for her part, is working on a research project about female agency in reproduction. The exchange between Dan and his students is particularly interesting, because it is nuanced and resists easy answers, and posits the body as a site of empathy and imagination, as much as of power. This is, of course, the same drive that animates the book as a whole – it is bodies, human and animal alike, that take centre stage here, and that govern the narrative decisions. The Breeding Season isn’t always successful, but it has a verve and scope that are exciting to read nonetheless.

Comments powered by CComment