- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Photography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

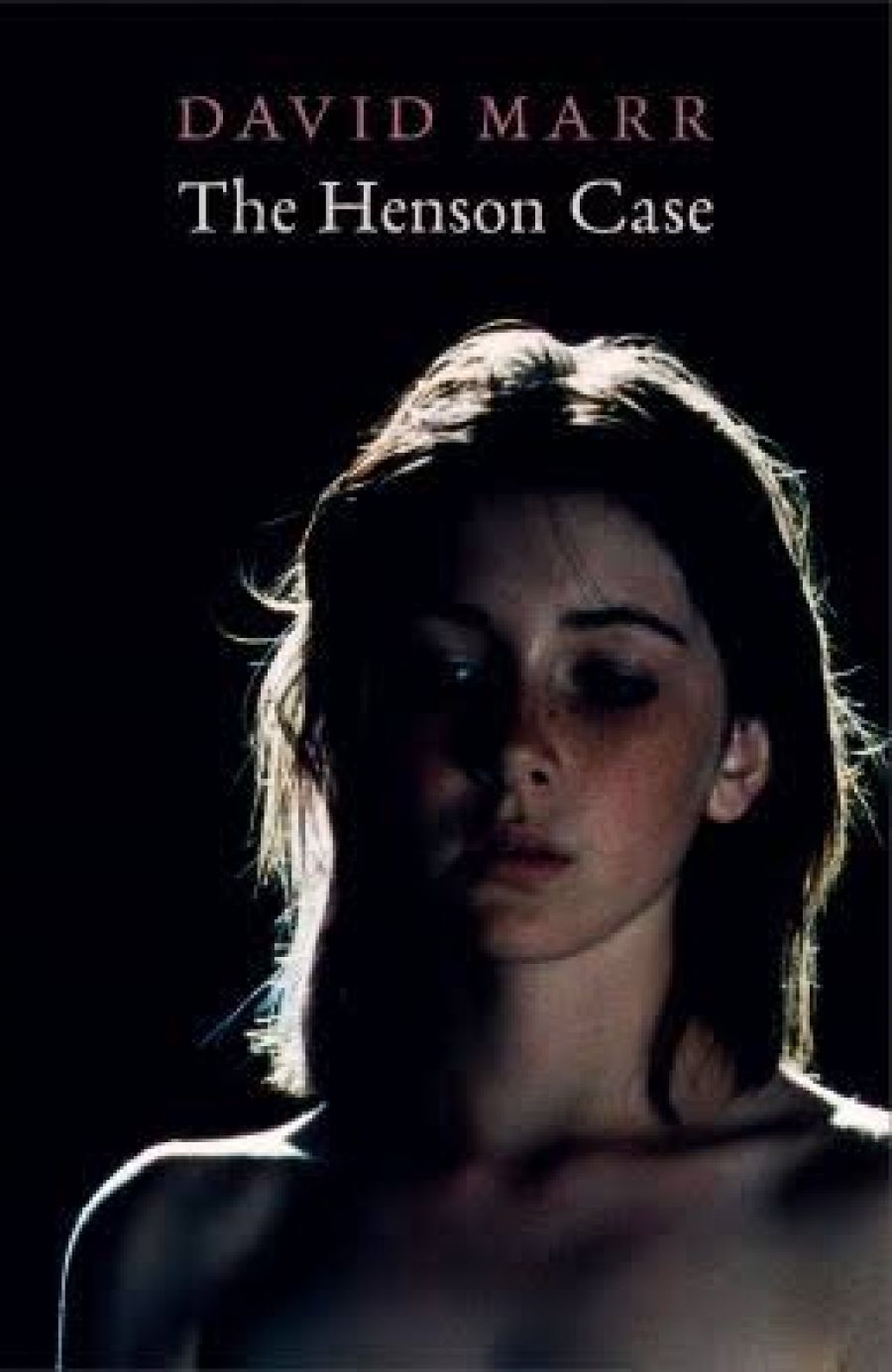

- Book 1 Title: The Henson Case

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $24.95 pb, 149 pp, 9781921520037

Panic, David Marr has stated since the publication of this book, is what he writes about: why people panic, what they panic about, and how they express it. Clearly, with his investigative skills and his access to different worlds, Marr was the ideal person to examine the so-called Henson affair.

The story itself is by now depressingly familiar, but few if any saw it coming. Bill Henson, a Melbourne photographer, had been practising his art since the mid-1970s. A few years ago, in Sydney and Melbourne, more than one hundred thousand people saw a major exhibition that featured studies of nude models, some of them quite young. There were no complaints, no public outrage. Henson’s work has been exhibited abroad, several handsome catalogues have appeared, and he has cultivated a number of influential supporters, David Malouf and Edmund Capon among them.

Everything changed with Henson’s latest exhibition at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, in Sydney. The invitation featured a portrait of a naked girl who is now referred to as ‘N’. Roslyn Oxley had reservations about the choice of image (‘I was always a bit worried about it. I thought, “Bill aren’t you going a bit far?”’), but the artist prevailed. The choice, in hindsight, seems almost Wildean in its daring, its provocation, however unconscious.

Some people found the image perturbing. ‘The Henson invitation has few friends,’ Marr writes; many copies, according to legend, went straight into the bin. The first person to raise the alarm was the arts editor of the Sydney Morning Herald, who thought it was ‘a bit off’. In her SMH column on May 22, the day of the opening, Miranda Devine cited the invitation and decried the sexualisation of children. Within hours, the thunderers of 2GB became involved, and with this any civility, any balance, any nuance, any respect for a renowned artist, went out the window. Chris Smith (‘one of Sydney’s most aggressive broadcasters’, according to Marr) led the charge: ‘It is disgraceful. It is disgusting. It is pornographic. It is woeful.’ His colleague Philip Clark was equally adamant later that afternoon: ‘I was appalled when I saw these photographs, I really was … Look, people go to jail for possession of images such as these … Don’t tell me they’re not pornographic because they are … And wankers walk around with glasses of champagne and call it art.’

Inevitably, given 2GB’s grim sway with politicians, one of them quickly obliged. Barry O’Farrell, Leader of the Opposition in New South Wales, became the first politician to denounce Henson (though he had been through the retrospective in 2005 without being troubled by any of the works). Morris Iemma, the serving premier, followed suit: ‘As a father, there is no way in the world I’d want my daughter to be in that position.’ Before long, Hetty Johnston, executive director of the child protection lobby group Bravehearts and scourge of Archbishop Hollingworth as governor-general, became involved, offering a brisk new definition of art: ‘Pictures portraying sexualised imagery of young girls can never be called art. It is child pornography, child exploitation and it is a crime.’ When the police were alerted, an inspector asked a guard at the Art Gallery of New South Wales if they had any ‘nude underage art works’. The best line in the book goes to Ben the guard: ‘I’ve only just started here … but it is an art gallery so there have to be some nudes.’

So inflamed was the situation that the opening was quickly postponed. ‘The jocks at 2GB had done well,’ Marr observes; closing down an exhibition none of them had seen. The cognoscenti repaired to the Oxleys’ house on the tip of Darling Point. Here, Marr’s trademark dryness is to the fore. While local silks ‘were delivering Opinions gratis on the lawn’, the Melburnians consoled themselves that such things could never happen down south.

Worse followed in the morning, with the prime minister’s intervention. Shown the images on national television (thick bars covering N’s nipples and heavily shaded genitals), Kevin Rudd said, ‘That’s the first time I’ve seen them. I think they’re revolting … Whatever the artistic view of the merits of that sort of stuff – frankly I don’t think there are any – just allow kids to be kids, you know’ (my emphasis). Marr notes: ‘Rudd was the only [politician] to declare after a cursory examination on a television monitor that they were without any artistic merit at all.’ A different kind of leader might have found subtler ways of expressing concern without belittling a serious artist. Marr expresses many people’s disappointment with Rudd, though the analogy with John F. Kennedy (‘… with these remarks on Today, Rudd killed Camelot’) is not entirely persuasive. ‘My name is Kevin, I’m from Camelot, and I’m here to help’ doesn’t have the right ring.

Among the politicians, only Malcolm Turnbull, not yet the federal Leader of the Opposition, emerged creditably, reminding journalists that we live in a free society and that freedom of artistic expression is rather important.

In the upshot, twenty police descended on the Oxley Gallery and seized several photographs. Shrewdly, the Oxleys employed a spin doctor, Sue Cato, whose tactic, as Marr notes, was ‘to starve the media into silence’. Henson, mystified by all the fuss and indifferent to public concerns about the internet (a creative and liberating medium, in his view), made no statements while he waited to see if he would be charged. Major art institutions, including the National Gallery of Australia, were raided by the police. Marr notes that the NGA’s director, Ron Radford, and AGNSW’s Edmund Capon himself – dependent on federal and state funding, respectively – chose to remain silent about Henson. The National Gallery of Victoria was more vocal in support of the photographer. Allan Myers QC, president of the trustees, remarked: ‘I don’t think Australia has been very tolerant of artistic expression – ever. I don’t think things have got worse, they are still bad.’

The resultant furore dragged on for weeks, rarely edifyingly or predictably. The chapter in the book about the ‘creative’ veterans of the 2020 conference and their efforts to reach consensus is not very riveting. Elsewhere, a number of minor artists became involved, drawing attention to their own work.

In the end, of course, no charges were laid against Henson or the Oxleys. Still, commentators queued up to have their say on the OpEd pages. None of the responses was more bizarre or sententious than that of the Melbourne philosopher John Armstrong, who, writing in the Australian on October 10, informed readers that the New South Wales police had asked him to help with ‘the central question: What is art?’ (really, the scene is worthy of Joe Orton). Armstrong then advanced the risible notion that, because Goethe, ‘recognising the common standard of the society in which he lived’, suppressed certain poems that might have given offence to ‘good people’, Bill Henson (despite the fact that ‘he has not done anything illegal’ and ‘has not harmed any of his subjects’) should ‘sacrifice his artistic project, in this area ... stop photographing children and concentrate on other valuable and beautiful work’. Warming to his woolly, antediluvian theme, Armstrong went on:

For a long time, art has lost its way, and this is a disaster for not only what is called the art world, but for the whole of society ... The true task of art is to show us ideals ... Its task is to civilise us, to make us sweeter, wiser and more noble, and to do so in ways that catch hold of the deep longings in ourselves to be like that. When art goes astray, when it gives itself lesser goals, all of society is vulgarised.

Sweeter and nobler, indeed. And who said art has ‘lost its way’ or has some kind of responsibility to ‘civilise’?

Marr, throughout, is clear-eyed – no ‘apologist’. Interestingly, he had never met Henson before writing this book. The portrait of Henson, with his immense self-assurance, is absorbing. The tape is rolling, and the artist has his head:

It never occurred to me that I’d ever be in this situation. You have got to bear in mind that, for better or worse, my work has been pretty much at the centre of the visual arts culture in this country for a long time … [When] your images are fluttering from one end of Macquarie Street and Martin Place to the other … you are pretty much as central to the debate on arts as can be. Next stop is footy.

Henson goes on to discuss his search for new models. ‘Look, just Google me, and I’d be very interested in photographing your daughter or son,’ he tells interested parents. But even Henson (‘not a man to volunteer mistakes’, according to Marr) must now regret his revelation that he has looked for models in primary schools, a further entrepreneurial use of public schools. This revived the affair on the publication of this book, generating obloquy that may prove even harder to staunch than was the case in May. But what of churches and sporting groups and talent scouts that ‘scour our schools’? And what of Kevin Rudd (freshly revolted all over again by this passage in The Henson Case)? Do his regular visits to schools distract pupils from their studies? Is parental permission always sought for the cloying footage on the evening news?

In this enthralling little book, David Marr is less spiky than usual. He is too worried to be mordant. He has reason to be. More was endangered after May 22 than a few contentious photographs. Wowserism, philistinism, censoriousness – never far below the surface in Australia – were given new life. Much became clear in the aftermath: politicians’ contempt for modern art; the readiness of the media to defame an artist without looking at his work; the refusal to distinguish between nudity and sexuality; the advent of a new puritanism; and the eagerness to jeopardise hard-won values and rights in a liberal society.

Something has gone awry here. It reminds us of one of Bill Henson’s moody, enigmatic photographs of a long curved road leading into menacing night, shadowily peopled.