- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘None but the brave’

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

For Labor ‘true believers’, the night of 24 November 2007 was one to cherish. In the north, Brough the Rough was despatched and a host of lesser figures swept away, pork barrels and all; in the very heartland of the Howard battlers, the Wicked Witch of Penrith and her minions perished in a jihad of their own devising; above all, in his fortress of Bennelong, the Vampire King was slain by the Good Witch of the ABC. What a night! At the beginning of Peter Costello’s memoir is the challenge: ‘How did it come to this? How did a government that had created such an Age of Prosperity, such a proud and prosperous country, now find itself in the wilderness?’

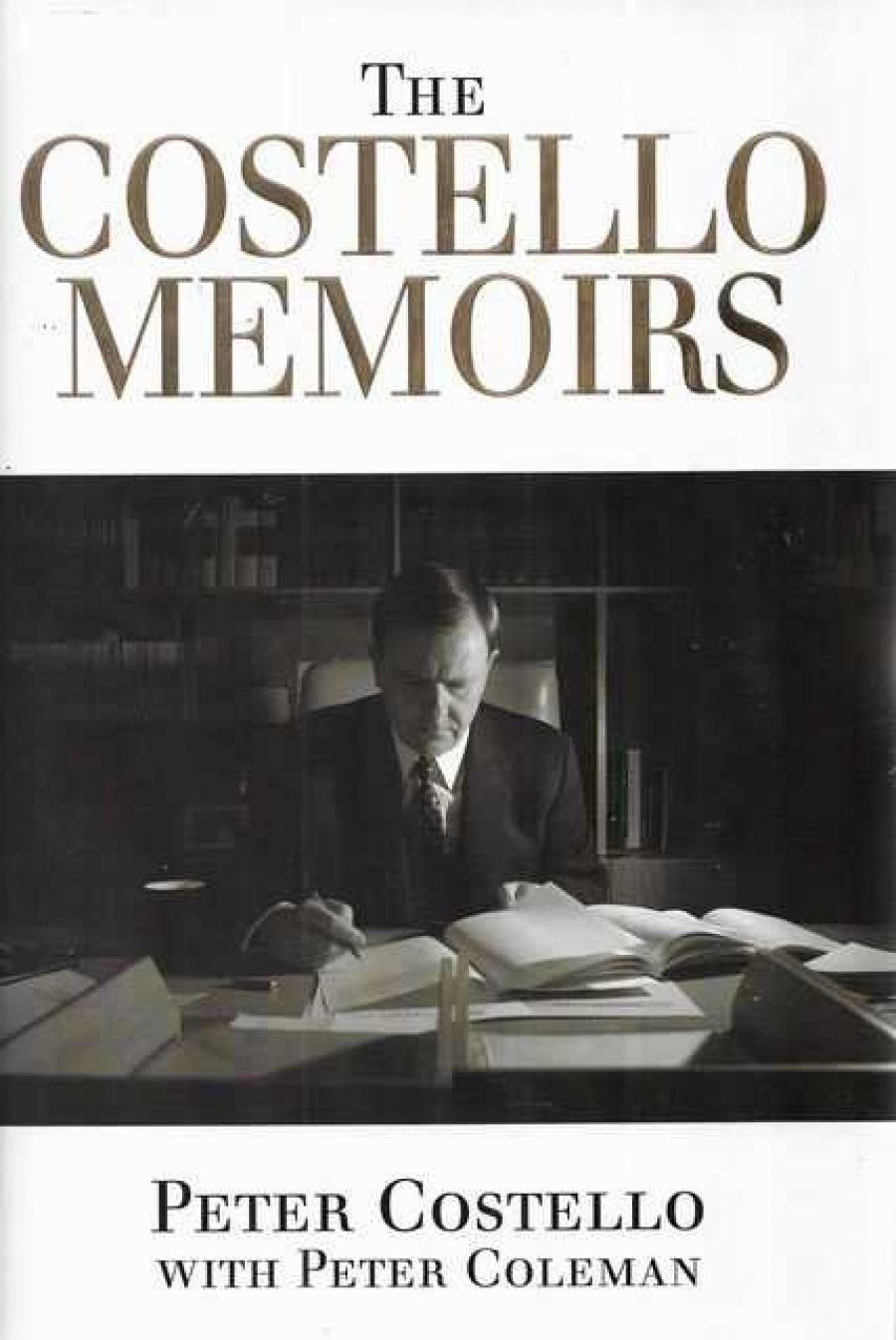

- Book 1 Title: The Costello Memoirs

- Book 1 Subtitle: The age of prosperity

- Book 1 Biblio: MUP, $55 hb, 386 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

You have to read to the end of the book for an answer. This is no bad thing, for a little suspense helps a book that, although substantial, is bland and hardly a riveting read. One reason for this is that Costello is just too nice. While he can be dismissive of those outside the tent, there is scarcely a harsh word for any of his Coalition colleagues. Roger Shipton, whose seat he took, is ‘good-humoured, good-natured, hardworking’; John Fahey ‘a valued friend … a great raconteur’; Peter Reith ‘an able contributor’; Warwick Smith ‘intelligent, affable … able’; Joe Hockey ‘affable … good company’; John Anderson ‘a decent man’. Only occasionally do the character sketches rise above the banal: Tony Abbott ‘saw himself as something of a romantic figure, a Don Quixote ready to take on lost causes’; or Amanda Vanstone ‘a bon vivant [who] cut a colourful figure in Australian politics’. He is even restrained when writing about John Howard – much less frank and fearless than when he talked in 2006 to the authors of the latest Howard biography. One misses the elegant savageries of a Paul Hasluck or even the cruder caricatures of a Mark Latham.

Nonetheless, a few are treated with scant respect. John Hewson as leader is presented as an inexperienced, paranoid zealot, indeed characterised as ‘a maniac’ on one occasion. Jackie Kelly gets unfavourable attention, but essentially as a surrogate for Costello’s loathing of the class of 1996, for many of whom ‘the Liberal Party was the Howard Party’ and therefore a major obstacle to his own ambitions. He has little time for Barnaby Joyce who was ‘able to grandstand on practically every issue … felt no loyalty to the Coalition … [and] made the life of the National Party Leader a misery’. Malcolm Turnbull gets a couple of flicks for being too big for his boots. It should be noted that three of these have no vote in Costello’s political future, if he should have one, and the other is his rival in any battle for command of the Liberal Party.

On many of the great issues of the day, Costello is on the side of the angels. He opposed the blocking of supply in 1975, and experience has made him ‘less sympathetic than ever to the argument from a hostile Senate that it knew better how to allocate Budget spending’. Tell that to the present mob! He thought the ‘Joh for Canberra’ push in 1987 ‘bizarre and politically whacky’. He supported the republican referendum in 1999, though he favoured the most minimal of republican models. He wanted ‘to go all-out to expose [Pauline] Hanson and her policies’ early on, and led the way by putting Hanson last on his constituency ticket. In a thoughtful and deeply sympathetic chapter rather brashly entitled ‘From Mabo to Mal’, he indicates that he favoured an apology to the Stolen Generations and supported reconciliation, wishing to join the march across the Harbour Bridge.

Even more relevant to contemporary controversies, we learn that he favoured signing the Kyoto Protocol, had advanced an emissions trading scheme as early as 2003, and had been advocating that ‘the Commonwealth take responsibility for water regulation in the Murray-Darling basin for some time’. These examples illustrate perhaps how uninfluential the second most powerful figure in the Howard government was on matters outside economics, since on nearly all of them he was rebuffed. Such is his discretion we learn very little of the constellation of forces arrayed against him.

Costello’s niceness is revealed again in a dislike of discussing nasties. Though nearly a chapter is devoted to his first budget, in 1996, whereby he corrected the deficit bequeathed by his predecessors, not one single concrete example is given of any of the savage cuts or broken promises that were necessary to achieve that objective. Although he provides a lengthy and rather arid debater’s defence of the intervention in Iraq, there is but a passing reference to the ensuing quagmire. There is only a single paragraph touching upon WorkChoices. Amazingly, he manages to write a whole chapter on the 2007 election without once mentioning the term WorkChoices or whatever other nomenclature was then in place.

The real interest of The Costello Memoirs lies in his economic stewardship and his rivalry with Howard, matters which constitute the heart of the book and nearly half its pages. On page two we are told, ‘Over eleven and a half years we had delivered the most successful period of economic management in Australian history. We had lowered interest rates, brought unemployment to historic lows, eliminated Commonwealth net debt and managed the longest period of uninterrupted growth our country had ever known. We had turned Australia from the “sick man of Asia” into a respected regional leader. We had built an Age of Prosperity.’ In case we had forgotten, three hundred pages later he reminds us: ‘After nearly twelve years at the helm of economic policy I could see what a different country we had become. We had built an Age of Prosperity.’ He loves this last phrase, using it as the subtitle of his memoirs. Hubris is lurking in the economic sections, and one can sense the notorious smirk hovering here.

Costello has much to be proud about. His courageous budget of 1996 laid the foundations for the fiscal strength of the government over the coming decade. He formalised the independence of the Reserve Bank and the priority of inflation targeting, thus ushering in an exemplary period of monetary management. He carried through, at considerable political risk, the task that had defeated both Keating and Hewson – the implementation of the GST – thus securing the revenue basis of the state. During the Asian economic crisis, he played a major role in assuaging the economic pains of our neighbours through generous assistance and by working to moderate the often unrealistic structural reform programmes of the IMF. In the new century, he presided over unprecedented years of tax relief, though some might argue that this was squandering the gains of the Age of Prosperity.

Such hubris ignores the contribution of others, including Keating and Howard. You would never learn – apart from a hint on page 271 – that there had already been nineteen consecutive quarters of economic growth when Costello took over the Treasury in March 1996, or that this growth was already accompanied by low inflation. There is no acknowledgment that Keating’s ‘recession we had to have’ in 1990–91 and the recovery from it created, for the first time in a generation, stable growth without inflation. Nor is there any acknowledgment of the contribution made to contemporary prosperity by the Keating structural reforms: the floating of the dollar, tariff reform, deregulation, enterprise bargaining. Costello was the superior economic manager; Keating the more creative treasurer.

Howard is a rather shadowy figure in the economic chapters. Costello’s absorption in detail – he confesses his fascination with tax policy is ‘a sickness’ – tends to obscure the making of economic strategy. We learn that the consumption tax was very much a joint enterprise with Howard, and that the tax relief measures were worked out together, but otherwise the prime minister appears as a bit of a drag on his treasurer. He would panic in response to populist arguments: in 1997 he effectively ‘killed’ the tax rebate on savings by declaring he would not claim it; in 1998 he gave the treasurer ‘a seizure’ by suggesting, at the last minute, in response to the welfare lobby, that the GST rate should be only eight per cent. Howard, too, was always nervous that tax relief might look too skewed towards the better-off and gave the treasurer, with his purist objectives, much trouble. Howard’s minor role in the economic chapters is in sharp contrast to the formidable obstacle he presents to Costello’s ambitions over the leadership.

The longest chapter in the book is given to leadership, ‘From Memo to Madness’: that is, from the McLachlan memorandum of December 1994 to the goings-on around the APEC conference in September 2007. In the penultimate chapter, Costello poses more succinctly and colloquially the question he asked in the opening chapter: ‘Why did the Coalition go cactus in 2007?’ His explanation for the disaster – the Federal Liberal Party ‘mismanaged generational change. We did not arrange the leadership transition’ – is essentially self-serving. According to Costello, if Howard had honoured his December 1994 undertaking to retire in favour of Costello after a short period as prime minister, all might have been well. Indeed, if some time in the ensuing eleven years Howard had passed the baton to Costello – in mid-2000 (the original commitment), or in mid-2003 (Howard’s sixty-fourth birthday), or in mid 2006 (when the original undertaking leaked) – the Liberal Party might yet be in government. Indeed, even after the surreal events around the APEC conference (in Costello’s words, ‘the week of madness’), Costello was prepared to accept the leadership and ‘try to win the election’.

Only one of these dates – 2006 – has much going for it in terms of the Costello claim. On none of them, except possibly late 2007, did he have the numbers to depose Howard, and by September 2007 it was too late. Despite Costello’s bravado, even Howard’s abdication at that late date could hardly have saved the Coalition government. In 2000 Costello recognised that, ‘weighed down with the GST, I was in no position to force the issue’. In 2003, after Howard had become ‘Bush’s man of steel’, it was difficult to quarrel with the leadership group’s assessment that Howard represented the best chance of their winning the next election.

But 2006 was different. Howard would be sixty-eight if he won the 2007 election and could scarcely expect to complete the term as prime minister. Among the leading Liberals, a number believed the time for change had come. Even the Howard loyalist Tony Abbott had told Costello in 2003 that 2004 would be Howard’s last election. Moreover, Costello could now plausibly argue that a leadership transition at this stage would not simply be the fulfilment of some pledge but in the best interests of the Coalition government. He still did not have the numbers. ‘My assessment was that a little more than a third of the 110 members in the party room … maybe a few more … would vote for a change in the leadership.’ He decided he would not challenge and go to the backbench, thereby ‘weaken[ing] the Government eighteen months out from the election’.

But neither did Keating have the numbers when he first challenged Hawke in 1991. Like Costello he believed that only by changing the leadership could the party win a fifth election. Unlike Costello he acted on that belief: it was a courageous step. If Hawke had not floundered in the face of Hewson’s Fightback, Keating would have been history. It is conceivable that, if Costello had behaved in a similar way in 2006, then, as Howard was blind-sided by the rise of Kevin Rudd, the Liberals might have turned to Costello as Labor had eventually turned to Keating. In those circumstances the Coalition might not have ‘gone cactus’ in 2007. Instead, by not acting, Peter Costello was left to ponder John Dryden’s (paraphrased) wisdom: ‘None but the brave deserves the [ch]air.’

Comments powered by CComment