- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A jealous mistress

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

My mother, a fine mezzo soprano, had three all-time favourite singers: Kathleen Ferrier, Maria Callas and our own Joan Hammond. When I was a child, my parents took me to see the famous diva perform Tosca in Melbourne – standing room only at the back of the circle. I remember red velvet, a thrilling voice, my own tired legs and a sense that I was in the presence of greatness. Sara Hardy’s biography of Joan Hammond (1912–96) is a timely publication. The number of people who remember the Australian soprano is dwindling, her fame eclipsed by another Dame Joan (who once, early in her career at Covent Garden, understudied Hammond in Aida).

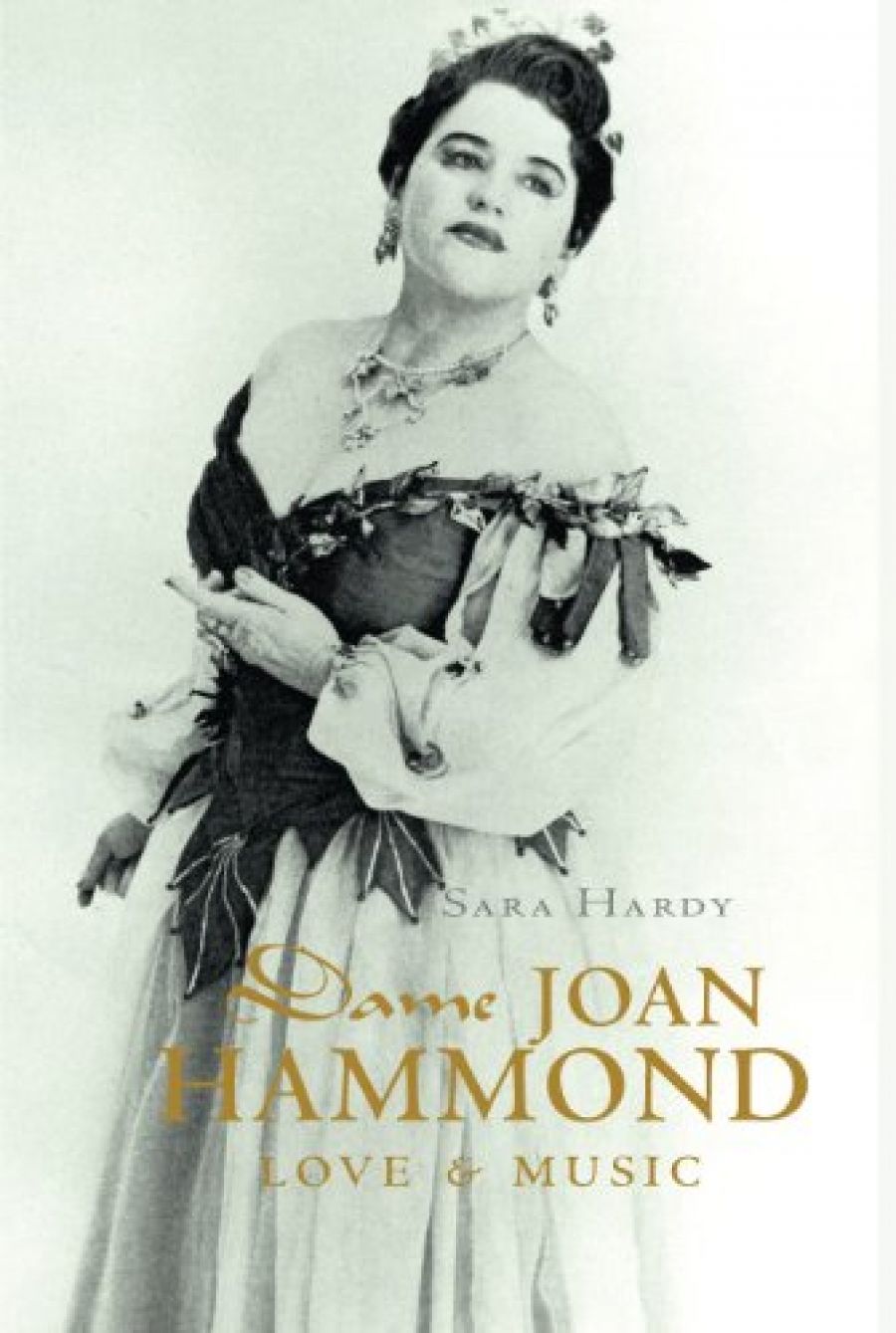

- Book 1 Title: Dame Joan Hammond

- Book 1 Subtitle: Love and Music

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $49.95 hb, 328 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Born in New Zealand to English parents, Hammond grew up in Sydney. She attended PLC Pymble – curiously as a boarder, though her parents lived only a few miles away. There she excelled at sport and music. Violin and voice vied with golf during those years, and her first taste of fame was as a championship golfer. When singing became her primary focus, it was through the patronage of Lady Gowrie, wife of the governor of New South Wales, that Hammond was given the opportunity of training in Europe, essential then (as it is now) for singers aspiring to an operatic career. Vienna was her destination in 1936. Over the next few years she moved between Austria, England and Italy, seemingly unaware of the escalating political tensions in Europe. Single-minded and focused on her singing to an extraordinary degree, the naïve young Australian was eventually forced by the declaration of war in September 1939 and the closure of theatres to cancel her return to the Vienna Volksoper.

This engaging biography takes the reader through the highs and lows of Hammond’s international operatic career, including her recordings of previously little-known arias – Puccini’s ‘O My Beloved Father’ and Dvorak’s ‘O Silver Moon’ – which she was to make her own. Hammond, with her Australian accent and down-to-earth ways, helped to democratise the high art of opera, performing some of her major roles in English, altering translations to suit the exigencies of the singing voice. She worked incessantly at her own interpretation of key roles such as Tosca, Butterfly and Mimi, and refused to study other performances of the roles. She also ventured into more experimental territory in Richard Strauss’s Salome, choosing to perform the Dance of the Seven Veils in a version especially choreographed for her, instead of using a stand-in ballerina.

One of the reasons why Hammond’s name is less well known than might be expected for someone who died only twelve years ago is that her singing career was curtailed by a heart condition, causing her retirement from the stage in 1965, at the age of fifty-three. Retiring to Australia from England, she soon embarked on a second career as Head of Vocal Studies at the Victorian College of the Arts, training and mentoring many young singers, including Peter Coleman-Wright and Cheryl Barker. Her influence was felt throughout the Australian opera world, and her professional experience as a practitioner was invaluable, not least on the question of curriculum. She insisted, for instance, that classes in language and movement were more useful to a singer than the study of advanced musical theory.

Hardy’s background in the theatre helps her bring to life the world of the singer: the smells of greasepaint and theatrical costumes waft from the page, and the trials of regional touring are evoked alongside the more glamorous aspects of operatic stardom. Hardy’s experience in writing about other women whose sexuality was ambiguous – such as Vita Sackville-West and Edna Walling – also makes her sensitive to the problems of interpreting Hammond’s domestic arrangements. Hardy prefaces her biography with an account of her disappointment at reading the phrase ‘Dame Joan never married’ in an otherwise glowing obituary of the singer. Obituaries, and biographies, tend to follow accepted signposts: career, marriage, children. These can be blunt markers, especially when writing ‘lives’ of those who cannot be boxed easily into conventional narratives.

When Hammond was asked by a journalist why she had never married, she replied, ‘Art is a jealous mistress’. And her art was paramount to her throughout her life. But Hardy’s subtitle ‘Love and Music’ (from Tosca) also alludes to the woman whom Joan first met at twenty and who became an integral part of the singer’s life for more than forty years. When Lolita Marriott died, Hammond wrote, ‘I am devastated’. Lolita’s name is on the Hammond headstone as her ‘loving companion’. Complicating matters is a third woman who was part of Joan’s entourage; Hardy builds a compassionate and sometimes hilarious picture of the eccentric trio who signed their names JoLoEss. Accounts by colleagues of champagne-fuelled parties at the house on the Victorian coast where large middle-aged women cavorted naked in the swimming pool might be lifted straight from the pages of an Elizabeth Jolley novel. (‘Jumbunna’ was Lolita’s project, funded by the Hecla heiress, although it was always referred to as Hammond’s house.) Hardy’s early observation that ‘[t]he private Joan was mischievous and teasing; the public Joan was gracious, and sometimes intimidating’, is amply borne out in the book’s subsequent pages.

Reminiscences by younger Australian opera luminaries enliven the portrayal of Hammond in the latter sections of the book. Lack of personal material is often a problem when writing about subjects who leave little in the way of personal archives and where few, if any, living contemporaries remain. In Hammond’s case, her memorabilia was lost in the Ash Wednesday fires that destroyed ‘Jumbunna’ in 1983. The earlier sections of the book are largely dependent upon a useful but ‘public’ autobiography written by Hammond after her retirement from the stage. (That said, a family skeleton definitely not referred to by Hammond is uncovered, and Hardy reflects on the odd relationship she seems to have had with her parents.) Perhaps the strictly chronological structure of the biography exposes the inevitable shift of tone that occurs as the source material changes from public to more personal, but this is a minor quibble. Dame Joan Hammond is a lively biography of a woman who was usually described as ‘handsome’, published in an attractive, well-illustrated volume. But behind the hooded eyes that gaze from her studio portraits, Joan Hammond’s inner life remains concealed from scrutiny.

Comments powered by CComment