- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The power and the process

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Behind the Exclusive Brethren is the story of a religious group that goes to extraordinary lengths to remain ‘apart from the world’ but whose very ‘unworldliness’ is maintained by very worldly means. Journalist Michael Bachelard’s readable and balanced account of the Exclusive Brethren in Australia is informed by a broad understanding of the church in its international context.

- Book 1 Title: Behind the Exclusive Brethren

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $32.95 pb, 314 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

For those who enjoy a secular lifestyle, it is easy to understand why many people have left the Brethren. The sect’s obsession with shunning the sinfulness of the world has led to very restrictive rules: daily church attendance, no friendships with outsiders, no modern forms of entertainment (including novels, theatre or cinema), no questioning of church authority, no tertiary training. Such rules are not dissimilar to those practised in many fundamentalist churches that claim to ‘know’ the correct interpretation of the Bible. Yet, as Bachelard shows, the Exclusive Brethren are now very much part of the modern world. They run successful businesses (frequently using computers), receive government funding for Brethren schools, use the media to fend off attacks and have no problems with using the law to minimise the impact of outside scrutiny.

Bachelard demonstrates the extent to which some Brethrens have engaged with the political process while refusing, on religious grounds, to vote. Most controversially, serious lobbying has gained the sect access to substantial Commonwealth funds for its schools. If the author’s suspicions are correct, taxpayers’ money has been used to prop up a system that is deficient in public accountability and that discourages talented students from seeking a higher education.

The book clearly shows the willingness of some federal Coalition parliamentarians, including former Prime Minister John Howard, to be seen as supportive of the Brethren, but the reasons for this remain elusive. Bachelard’s evidence suggests two plausible explanations. Business-oriented Christian politicians may have had some natural affinity with the Brethren, or, alternatively, the desire of Liberals to appear ‘liberal’ in matters of religious freedom may also have been persuasive. At times, Bachelard’s political analysis could have benefited from a broader engagement with Australian political studies such as Marion Maddox’s God Under Howard: The Rise of the Religious Right in Australian Politics (2005). Reference to such works might have allowed him to construct bolder arguments about the Howard–Brethren connection.

There are a couple of instances where the author makes some minor overstatements about Australian politics. First, Howard is described as entering parliament ‘with an established reputation as an advocate for the “New Right”’. If Wayne Errington and Peter Van Onselen’s biography of the former prime minister is accurate, Howard’s early political career reflected more of a pro-business than a pro-free market attitude, although he was gradually forging links with the leading economic ‘dries’. Moreover, more research on Queensland political history would have prevented the author from implying that Ned Hanlon (premier from 1946–52) was ‘anti-union’. Hanlon was ‘anti-strike’, believing in the primacy of industrial arbitration courts in settling union–employer disputes.

On a more positive note, it should be mentioned that the author has gone to great pains to provide balance to his account. He is, to all intents and purposes, an advocate for the former members of the Exclusive Brethren whose families have been broken because of the sect, but has allowed spokesmen for the Brethren to have their say (although they choose not to say a great deal). The history of the Brethren, with all its twists and turns, is respectfully told, highlighting the whims of international leaders in influencing the ‘unworldly’ nature of the Exclusive Brethren. Bachelard also shows how the ‘worldly’ activities of the Brethren reflect the weaknesses of mainstream society and its infrastructure, especially the extent to which ‘cashed up’ organisations can gain special treatment and exemptions.

It is difficult for outsiders to come to terms with the ‘pull’ which a restrictive sect like the Exclusive Brethren has on its faithful membership. The evidence from Bachelard suggests that, for some members, the financial and organisational effort required to ‘keep the world at bay’ is a fascinating end in itself. Yet, one suspects, the reality for many members is more mundane: it is all they have ever known.

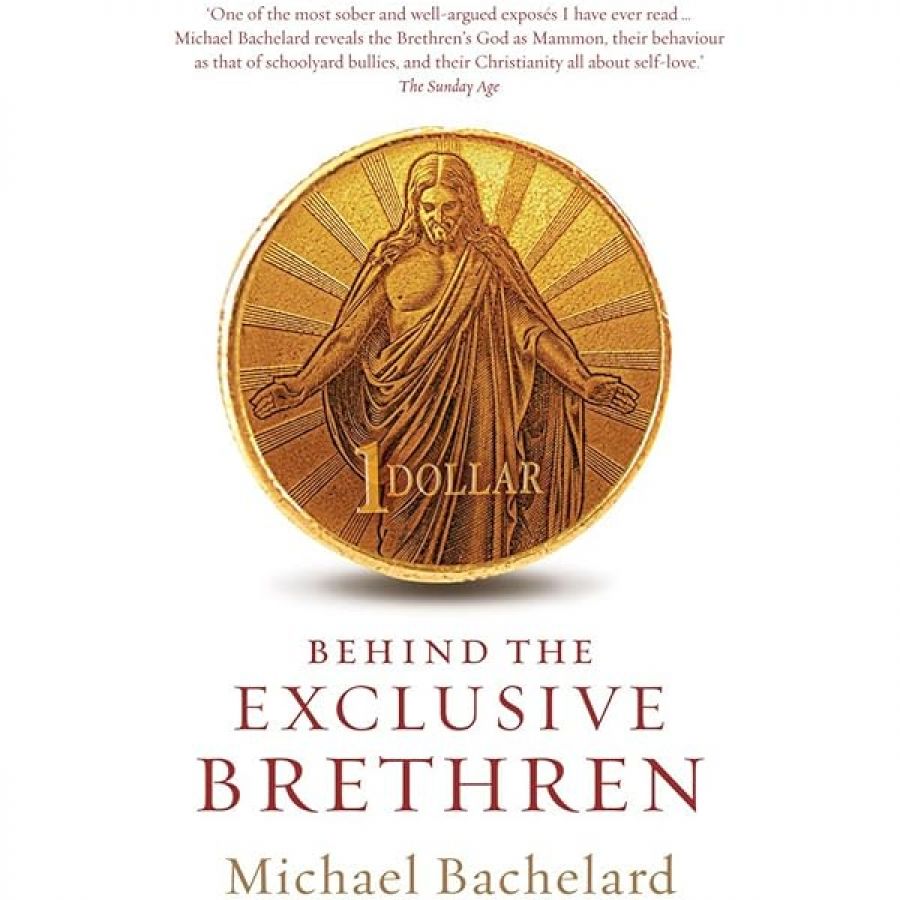

The book’s cover – a picture of a $1 coin dominated by an image of Jesus – is eye-catching but overly flippant. This is a pity, as the book is ultimately a serious, sensitively written account of a controversial and little-understood sect. Skilfully combining history, investigative reporting and impassioned advocacy, Behind the Exclusive Brethren is a great read.

Comments powered by CComment