- Free Article: Yes

- Contents Category: Calibre Prize

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Salt Blood

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

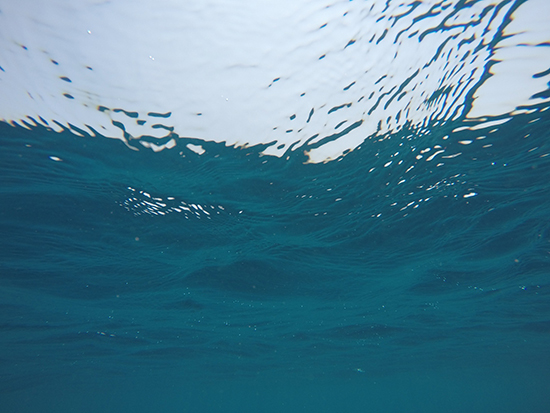

It is quiet and cool and dark blue. At this depth the pressure on my body is double what it is at the surface: my heartbeat has slowed, blood has started to withdraw from my extremities and move into the space my compressed lungs have created ...

Listen to this essay read by the author.

‘There are no words that fit tragedy. Nothing we can say. We do not want to be told everything is all right. It is not.’

Patrick Holland, ‘Silent Plains’ (2014)

‘Its constituents are – everything.’

Victor Hugo, Toilers of the Sea (1866)

It is quiet and cool and dark blue. At this depth the pressure on my body is double what it is at the surface: my heartbeat has slowed, blood has started to withdraw from my extremities and move into the space my compressed lungs have created. I am ten metres underwater on a breath-hold dive, suspended at the point of neutral buoyancy where the weight of the water above cancels my body’s natural flotation. I turn head down, straighten my body, kick gently, and begin to fall with the unimpeded gravitational pull to the heart of the Earth.

Freediving, or breath-hold diving, forms at once a commonplace and unique relationship between humans and oceans. Commonplace because we can do it from the moment we are born (having already floated in amniotic fluid for nine months), and because many native and local cultures in coastal areas around the world have long practised breath-hold diving. But also unique because ‘extreme sport’ competitive divers are now exceeding depths of two hundred metres on a single breath, and there are divers able to hold their breath underwater for more than eleven minutes. Freediving is both liminal and transgressive, taking place in a zone where few humans venture, and subverting norms about perceived natural boundaries. The practice of freediving mobilises what has been called the most powerful autonomic reflex known in the human body: the mammalian dive response.

While I have been a casual spearfisher for many years, I have only recently engaged with freediving in its contemporary expression. My first time freediving, I trained with divers from a centre in Bali. A small group of us spent the mornings alternating between dive theory and yoga practice, and the afternoons diving and talking. My instructors were Matt and Patrick, and my diving partner was Yvonne, young, German-born, with degrees in journalism and American Studies, and working locally as a scuba instructor. She had clearly spent a lot of time in the ocean, whereas for me it was never a profession or even an intense hobby.

On the north-east coast of Bali, Jemeluk Bay is wide and peaceful, sheltered from prevailing weather patterns, and lined with small fishing villages. The volcano Gunung Agung, the most sacred mountain in Bali, rises above the bay. The bathymetric chart highlights the continuity of the volcano’s slope deep into the ocean, depth falling away quickly from shore. We dive amongst the moored fishing boats, using a system of buoys and weights to establish guide lines into the depths. In the water, with one hand loosely on the line to keep myself oriented, I ‘breathe-up’, building the oxygen stores in my body. Visibility is about ten metres, then light disappears into milky blue darkness as I turn and dive. The white guide rope drifts past my mask until I reach the depth plate and pause, consciously relaxing my body, emptying my mind. I watch this world, bubbles float slowly upwards, jellyfish drift past, the sun is a diffuse white ball on the surface. It is distinctly different – thicker, darker, slower, heavier, more silent, and here I do not breathe.

Gunung Agung, Bali, Indonesia (photograph by Michael Adams)

Gunung Agung, Bali, Indonesia (photograph by Michael Adams)

As I fin back up, there is a burst of flickering light as a shoal of tiny blue fish hurtle through sunbeams at the surface. Head above water, there are distant sounds of the ubiquitous Balinese cocks, faint sounds from motor scooters. Diving again, my hearing transitions from airborne sound to waterborne sound. There is an intense crackle of snapping shrimp, fading as I go deeper. Faint sounds of women singing and the thrum of an outboard motor indicate a fishing boat passing nearby. After a few dives I start to close my eyes, removing the usual visual dominance to instead just listen and feel.

Two key aspects in freediving are equalisation, adjusting the pressure inside your ears to compensate for the increased pressure outside the eardrum that the water exerts with increasing depth; and responding to the ‘urge to breathe’, your body telling you insistently that you should breathe again, very soon, followed by involuntary spasms of your diaphragm, trying to make you breathe. Yvonne and I were both good at dealing with the urge to breathe, but we were not successfully equalising, and repeatedly had to turn back at ten metres, unable to eliminate the pain in our ears. I found this incredibly frustrating, and my diving ability declined as I became more tired and tense. Equalising is psychological as well as physical – taking down the walls of protection is difficult.

After the second day, I am completely spaced out, floating, serene. I sleep lightly through the tropical nights, dreaming of the dives, the patterns of light, the flicker of fish, the still blue. And I don’t really understand it: why does the mortal uncertainty of deep immersion feel nurturing, reassuring? When you are deep underwater on a breath-hold dive, the margin of safety can be very small, there is very little space between living and not: you are, both metaphorically and actually, quite close to death. I am old enough now that death is not an abstract proposition, I go to more funerals, and my near-adult children remind me of the place of death in my own childhood.

What presents itself to navigate this mortal, radical, uncertainty is grace. Physical grace means ease or suppleness of movement or bearing. It is a by-product of good freediving: the equalising of pressure across your eardrums and between your lungs and the crushing ocean weight, the streamlining of the external position and shape of your body. It is achieved by aligning yourself to the enveloping, immersive environment, the context and emotion of the place and time. Grace is important. We intuitively respond positively to seeing it in others (dancers, gymnasts, athletes) because it is good for us – to gracefully align ourselves to our environment. Physical grace is coupled with spiritual grace – it regenerates and sanctifies, and gives strength to endure trials. When you stop breathing, it’s good to stop thinking too.

Uncontrolled fear when deep underwater will spike adrenalin, trigger the flight or fight responses, and potentially kill you. You can’t fight and you can’t flee, you have to accept and relinquish all control, you have to trust: the crushing pressure of multiple atmospheres cocoons you in an embrace.

In practice, freediving is just holding your breath and diving underwater. It is as old as humans, and humans have long understood various aspects of how it is possible, but the knowledge is uneven. Bajau divers from the Philippines and Malaysia routinely suffer hearing loss through burst eardrums, and Greek sponge divers in the past often had significant hearing loss as well as symptoms of decompression illness. The women-only diving communities of Ama in Japan and Haenyno in Korea appear to dive deep long into old age with no ill effects, and have done so for thousands of years. Western spearfishers tend to know about equalising, but not so much about oxygen and carbon dioxide processes in the body.

Contemporary research interprets the physiology of freediving through the concept of the ‘mammalian diving response’. This is a combination of three independent reflexes that counter the normal bodily regulation of breathing, heart rate, and blood pressure, and it is described as the strongest unconscious reflex in the body. The diving response occurs in all mammals, and possibly in all vertebrates – it has been observed in every air-breathing vertebrate ever tested. It is obvious and prominent in human infants. Up to about six months an infant immersed in water will open her eyes, hold her breath, slow her heartbeat, and begin to swim breaststroke.

It is currently assumed that there are three triggers for the diving response: facial immersion, rising carbon dioxide levels, and increasing pressure at depth. These triggers result in reduced heart rate, redistribution of blood from bodily extremities to central organs, and contraction of the spleen. All these reflexes increase access to oxygen, either by reducing the rate it is consumed, or by changing its availability in the body. Learning to understand and recruit these processes enables freedivers to routinely reach depths of twenty to fifty metres, and to set records at depths of one hundred to two hundred metres.

From the land or the air, the ocean surface is opaque, mobile, vast, and dark. The World Ocean is animate, active, unstable, ungrounded, unfathomed. It covers seventy per cent of the planet’s surface and encompasses ninety-nine per cent of its inhabitable area. It is largely unknown. Ocean processes control the weather and continental climates. It defines the Blue Planet.

Once immersed, beneath that surface, the suck and swell of the tides feel like the planet breathing. We are surprised, sometimes anxious and then increasingly comfortable with the complexities of temperature and movement in the ocean. There are layers of warm and cold water; strong but invisible currents that can help or hinder us; be struggled against or relaxed into, rocking the body into peace. Our bodies begin to align with those rhythms: the cycle of the moon and the ebb and flow of tides, the fetch of the wind across the bay.

Mirroring our time in the tiny sea of the amniotic sac, freediving is the most profound engagement between humans and oceans: the unmediated body immersed and uncontrolled in saltwater. It is simultaneously planetary and intensely intimate – the ocean is both all around us and within us. That breadth of scale can be terrifying or reassuring. It is not about discovery, it is about recovery: we can freedive expertly from the minute we are born, but slowly forget. Our cultural preoccupation with growth and exploration washes away our embodied knowledge. Aboriginal people in Australia speak of how, if the Country is there, the knowledge is always there, and remind us to draw on the whole of the evidentiary base: the world, physical sensations, dreams, emotions – not just the ‘bedrock’ of Western reason. Sea Country keeps its knowledge too, waiting for us to find it again.

Ten metres, thirty feet, the point of neutral buoyancy, is five fathoms in the old marine depth measure, as in Ariel’s song:

Full fathom five thy father lies,

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes;

Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Fathom comes from the ancient word fæthm meaning an arm span, ‘something that embraces’. It also means ‘to understand’ – to get to the bottom of something. I didn’t start freediving to understand mortality, but that is the direction in which it has led me. Diving is the window that, for Simone Weil, ‘makes visible the possibility of death that lies locked up in each moment’. Herman Melville puts the same thought into the whaleboat, ‘it is only when caught in the swift, sudden turn of death, that mortals realize the silent, subtle, ever-present perils of life’.

Although he died when I was fourteen, I saw my father’s death certificate for the first time this year. Single word entries sketched the story: at age forty-five he was living in a caravan in north Queensland, working menial jobs. He sat down alone one evening on a beach with a handful of pills and a bottle of scotch to kill himself. He asphyxiated on his vomit and was found days later. Four brief entries on a faded government form, with a tsunami of hurt and loss behind them, and a flood of confusion and misunderstanding to come. I knew the basics of that story, but was not prepared for the shock of the typed words: ‘labourer’, ‘caravan park’, ‘suffocation’.

Reading a stranger’s words on my father’s death certificate reminds me how little I know about him. Because of some medical training before dropping out of university, he had good knowledge of pharmaceuticals. This helped him to find work with large pharmaceutical companies and gave him access to prescription drugs from the warehouse. I remember as a boy scavenging through boxes in those warehouses and using surgical tape to construct murderous crossbows with back-to-back scalpel blades as arrowheads. We moved around a lot as he and my mother held a number of jobs. My mother left when I was eleven, and I last saw my father when I was thirteen. My brother and I had lived in ten houses in five towns by the time I finished school.

My relationship with my own son through his mid-teens was fraught. My teenage years had been marked by binge drinking, drugs, and other risk-taking, but I rationalised that I was responding to a dysfunctional childhood, whereas he had two loving and supportive parents present, material security, and we lived in a beautiful place. I felt I had no road map and was just making it up as I went along. I had a stepfather in my own teens who took me into police cells and stood me in front of mangled cars with blood pooled beneath them to show me where I was going to wind up. I now wonder whether suggesting to my son that we go to a freedive school was pushing against, or mirroring, the patterns of my own past.

I have spearfished with him since he was less than ten years old, but in relatively shallow waters. One of the first times, as he stood next to me on the rocks above rolling swells, I asked him if he was ready, to which he said, ‘If being totally terrified is ready, then yes I am’ – and we stepped off into the sea. He is a long way past that now and far outstrips me in his ability and comfort in the water. During our first session in Bali, I watch his grace and skill as he fins down the line and disappears into blue depth past the limit of visibility. Then a long wait until he reappears, relaxed and unhurried. He interned at the freedive school, and has now repeatedly dived thirty and forty metres. On his first attempt at that depth, he paused at the depth marker and looked back to the surface. Freedive teachers tell you to not look up or down, to keep your spine straight, and five atmospheres of pressure ruptured blood vessels in his extended trachea so by the time he was back at the surface he was coughing blood.

Divers like to underplay these injuries, so it is called a ‘throat squeeze’. You can also have an eye or mask squeeze or lung squeeze. The medical literature defines these as barotraumas, pressure-induced injuries; they can be very common in freediving. You can also ‘samba’ at the surface (a loss of motor control so your body does a little involuntary dance) and finally ‘SWB’, shallow water blackout: both of these are a result of hypoxia or oxygen deficiency in the brain. It is increasingly assumed that shallow water blackout is the explanation for many diving deaths generally attributed to drowning. Shallow water blackout is achieved by either consciously enduring the contractions of your diaphragm (caused by increasing carbon dioxide levels) that are trying to force you to breathe; or artificially lowering those carbon dioxide levels with particular breathing practices, so you don’t get the contractions.

After my first freedive trip, I went back to riding a big motorbike and started yoga. The freediving, yoga, and motorbike are related practices. Yoga is not intrinsically dangerous, but yoga philosophy says ‘when you hold your breath you hold your soul’. Breathing out, expiration, is a little reflection of that last gasp of death; to expire means both to breathe out and also to die. The physical movements and breathing practices of yoga take me to a place of emptiness and peace: when the breath is still, the mind is still. The BMW demands presence: it is really not good to daydream on a motorbike. I ride nearly every day, in all weather, and statistically that will likely eventually lead to an incident. But when that happens, adrenalin and reflexes come to the rescue. Diving and yoga remove adrenalin and bring quiet and stillness; the motorbike and diving bring presence in danger.

Bruny coast (photograph by Michael Adams)

Bruny coast (photograph by Michael Adams)

One winter I dived off South Bruny Island, Tasmania. Bruny was home to Tasmanian Aboriginal woman Truganini. During my school years we were told Truganini was the ‘last of the Tasmanian Aboriginal people’, effectively erasing the lives of the many descendants of Aboriginal people and various settler–colonist communities. I harvested from the ancestral waters of Truganini’s Neunone people: cold, deep water, rich and beautiful: abalone, oysters, mussels, edible seaweeds, wild spinach. The abalone industry is worth $100 million a year but excludes many Aboriginal people because of the exorbitant cost of licences, despite a 40,000-year history of sustainable harvest demonstrated by numerous shell middens. Current active divers are arguing that the stock is on the verge of collapse after only four decades of over-intensive harvest.

Walking the tidal edge on Bruny, I kept thinking about Joseph Conrad’s words at the end of Heart of Darkness (1899): ‘the tranquil waterway leading to the uttermost ends of the earth flowed sombre under an overcast sky – seemed to lead into the heart of an immense darkness’. Tasmania is not so far from the uttermost ends of the earth, and it has a dark history, palpable in the landscape. The idea of ‘Tasmanian Gothic’ is not new, with writers Richard Flanagan, Rohan Wilson, and others exploring the psyche of the Van Diemonians. Rohan Wilson’s The Roving Party (2011) is perhaps the most successful book I have read in presenting how Aboriginal people, in all their diversity, were totally compromised by the violent colonial process: there were no right decisions to be made, especially in Tasmania: all decisions had terrible consequences. (After leaving Bruny I discover, astonishingly, that the rusting hulk of the Otago, the only ship that Joseph Conrad commanded, lies near the shore of the Derwent River in Hobart.)

My first attempt diving at Bruny was short. It was morning, mid-winter, calm, and I had just seen a trio of dolphins cruising slowly along the shore of the D’Entrecasteaux Channel. I slipped into deep water from a boat jetty and was immediately shocked by the intense cold, less than ten degrees by my dive watch. I submerged and finned west across the channel towards Satellite Island, but with visibility only two to three metres, an instant cold headache and paranoia about hypothermia, I opted out.

The second try was at Cloudy Bay, also very cold but I dived for forty-five minutes. Visibility was still limited, and big swells rolling unimpeded from Antarctica meant I could not get near to the underwater bull kelp forests, which seem to like high-energy coasts. Black cockatoos and a pair of sea eagles watched while I dressed, shaking with cold, on the rain-soaked beach.

Before Tasmania, I dived at Honaunau Bay on the Big Island of Hawai‘i. Like Jemeluk Bay, this coast is dominated by the volcano Mauna Kea – to Native Hawaiians the most sacred mountain in Hawai‘i, and the tallest mountain in the world if measured from the sea floor. The first day I am just testing my gear. This is my first time diving since I scuba-dived with students on a field course. I have heard someone compare scuba diving to driving though a forest in a four wheel drive with the windows up and the air conditioning on – and that was definitely my experience – I kept wanting to stop breathing to cut out all that noise, all those bubbles, to reject the cyborg and hybrid paraphernalia. Diving at Honaunau Bay was the opposite – serenely quiet except for the crackle of shrimp and the slap of waves.

I am diving with Daniel, an instructor from southern California who has relocated to the Big Island. Daniel is very experienced and very, very relaxed in the water. Again like Jemeluk, Honaunau Bay is unique in having great depth close to shore: the bathymetric chart here shows that within a hundred metres of shore you can be in a hundred metres depth of water. I have never been in water that deep; on the first day I have trouble relaxing with all that blue falling away below my fins. Being relaxed is really important in free diving – I wind up with continuous cramps in both legs.

On my third day diving we are joined by Shell, a quietly-spoken instructor and international competitor. A month after we dived together, Shell became the US women’s champion in the pool discipline of ‘dynamic no-fins’, swimming 125 metres underwater without breathing in less than three minutes. Diving with Daniel and Shell was calm but rigorous, with detailed safety processes and checks. Shell was quietly experimenting with a nose clip and no mask, and Daniel was safety diver for us both as we alternated dives.

A year later, I dive in a very different way at Honaunau Bay, this time with legendary diver Carlos Eyles. All my diving so far had been within the established structures of modern freediving, with guide ropes, floats, marker plates, and lots of focus on metres of depth, minutes of breath-hold, Boyle’s law, and the physics and physiology of pressure. Of all the people I have dived with, two gave me stark lessons about my own attachment to this linear thinking. Rayanna, a young Brazilian woman I dived with in Indonesia, and an excellent freediver, never used a dive watch, did not measure her depth or breath-hold, and helped me throw away the numbers. In Hawai‘i, Carlos, who is seventy-five, did not talk about technique at all: we sat at the edge of the water and talked about philosophy for an hour before our dives together, then he taught experientially – I copied his movements. He called it ‘catching the rock’, demonstrating the analogy that we cannot teach through linear thinking or communication how to catch a thrown object, our brains can’t compute the distances and movements and decisions, we learn it bodily. We dived for an hour or so, then swam together for about a mile, out to the northern point of Honaunau Bay and back. Next day I went back and repeated it all, but this time alone, breaking the cardinal rule of modern freediving.

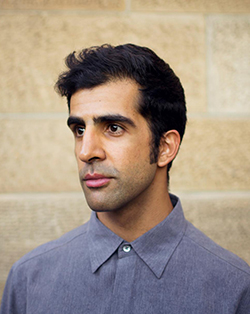

Michael Adams, Honaunau Bay, Hawai'i (Photograph by Daniel Koval)

Michael Adams, Honaunau Bay, Hawai'i (Photograph by Daniel Koval)

The core and obvious lesson for me from Carlos was ‘the ocean is not a linear system’. Non-linear systems are typically described as counter-intuitive, unpredictable, or chaotic. We can think of the ocean like this, as vast, turbulent, shifting, untamed, unknowable – the dark abyss. Floating above one hundred metres of blue depth, that abyss felt very real. As Carlos says, soon sharks will start circling in your pre-frontal lobes: they are just out of sight, but you are sure they are there. Carlos talked about this fear, and how you had to throw away these acculturated imaginings, these death anxieties, and focus on your body’s ancient knowledge. When the fear is there, those monsters of the deep, you lose grace. Finding grace opens you to transformation. Feeling the ocean all the way through your body, seeing it in every direction you can look, experiencing sound and silence and light transformed by the depth and thickness of water – these embodied experiences unground our linear, rational, bounded structures of thought. We can let go of the anchor of imagined and irrational fears, and swim free with humility and attention. Swimming and diving alone on a quiet hot morning in Honaunau Bay, feeling strong and comfortable in my body, I am slowly unmoored, slowly floating away from risk assessments and calculations and into the warm embrace of the peaceful bay.

This ocean, these waters, are full of life and agency. Most of life lives in the sea – fifty to eighty per cent of all species live there. Their agency is palpable – their intention, attention, awareness, and presence in the rock, coral, sand, and saltwater. So while I was alone, I was also not alone, I was surrounded by innumerable other beings, all going on with their lives and deaths in the sea about me.

In the tidal wave of current discussions about extinctions, biodiversity loss, and planetary crisis, a less visible current of knowledge pulls at our attention. Everywhere, there is both abundance and loss, thriving and declining. What we term weeds, or feral species, or invasive species, or common and abundant species, are plants and animals thriving in place, and it happens everywhere. In all the world’s oceans, while many apex predators are depleted, populations of cephalopods (squid, cuttlefish, and octopus) are increasing, despite continuous and heavy fishing. Cephalopods are particularly interesting, with complex intelligences described by Peter Godfrey-Smith in 2016 as ‘an independent experiment in the evolution of a large nervous system, the only such experiment outside the vertebrates’. In my local seas, octopus and giant cuttlefish are quite common, often curiously investigating us as we examine them. My local rocky shores are also home to the only cephalopod that can kill a human, the tiny and potently venomous blue-ringed octopus. Hundreds of human families play in that habitat daily with no fatal encounters; we peacefully share the space. Because we have forgotten this truth, that we can share, that we are all connected, planet and landscape and seascape and human and innumerable other species, we have lost perspective on change, and these become liminal experiences: looking into the large, thinking eyes of octopuses and giant cuttlefish; sinking into depth, eyes-closed, past the buoyancy zone; embodying the visceral sense of release and lightness of diving on empty lungs.

Liminality is a threshold state, the border between one condition and another. It is not either of them, it is ambiguous and disorienting. In many cultures, there are three stages in the liminal transition: a metaphorical death, a test, and rebirth. The liminality of freediving has multiple dimensions. It connects us to ancient stories in many cultures of mermen and mermaids: beings between human and water creature. Western cultures know them as sea-nymphs, nixies, silkies, etc. Miskito Indian divers in Central America call these beings liwa mairin, and in modern times attribute decompression sickness and other diving illnesses to the inimical moods of these water spirits. Diving is also in the boundary zone between earth and water, with air the defining element. It moves from light to increasing darkness with depth and back again. It moves from swimming down against the natural buoyancy of the human body, to free-falling with gravity as increasing water pressure overcomes that buoyancy.

And it is liminal between life and death – at great depth, you have to be exquisitely attuned to the totality of your body if you want to keep on living. You have to understand the symptoms of oxygen depletion in the particular way that it is expressed in your own body, and confidently know how much time you have to continue swimming deeper, as well as make the return journey to the surface before you black out. I keep in my journal a graph illustrating this relationship, with red and blue lines showing trajectories of living and dying. Free- divers I spoke with indicated there can be a wide range of physiological indications of oxygen depletion, and they had learnt quite specific cues to which they would respond. Despite this, many experienced freedivers assured me that death is seldom in their thoughts. The safety framing in recreational freedive training and diving is usually rigorous and very careful, with a number of key rules described as ‘safety through redundancy’, designed to keep divers well within the limits of what is safe for them individually. This is reinforced by the buddy system, so you never dive alone. Spearfishers, routinely self-taught, tend to be less particular in their approach, with hyperventilation often a common practice, and many spearfishers diving alone. Lifelong surfer and diver Tim Winton embodies this, with many lyrical passages in his writing reflecting the casual acceptance of these risks.

Moving away from the regulated structures of safety and risk control lead you onto the rocks of danger and uncertainty, and danger and uncertainty, normal in most of nature, are the complements of safety and fulfilment in life. To live amidst all of these you need to be present, attentive – you need to learn to fail better. Tibetan Buddhist Pema Chödrön argues that ‘all kinds of things happen that break your heart, but you can hold failure and loss as part of your human experience’. You need to find again your ancient bodily wisdom, your heart’s knowledge that while we are all alone, while there is always hurt and loss, your strength and beauty and intelligence and love are transmuted through your life’s relationships and work to be reborn in others.

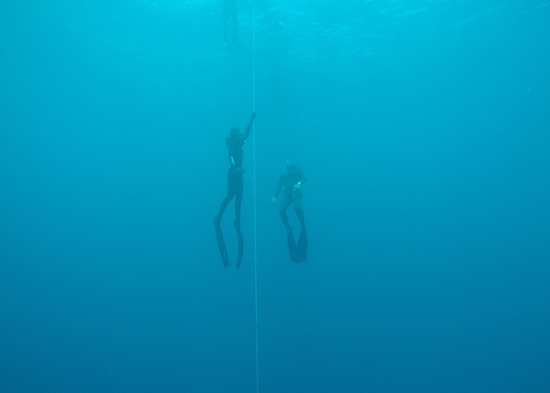

(Photograph courtesy of Michael Adams)

(Photograph courtesy of Michael Adams)

I have failed to understand my father’s suicide all my life. There was no note, no message, I had not seen him for a year. Freediving has shown me a new way to understand death. In the yoga traditions, breathing in engulfs you with life. Breathing out generously gives that life back out into the world. After deep practice of yoga breath control, pranayama, the need to breathe often falls away for long, relaxed minutes. As the water closes over my head each time I dive, I let go my earthly concerns to sink into the blue embrace of an alternate world. On that dune in the tropical night, my father took a different measure on his life and cast off his quotidian moorings. One of those moorings was me, and I have to fathom the place in my life of both harbour and open sea, port and storm.

In freediving I often think about death, but it is not always ‘death anxiety’ as the psychologists construct it. There is real danger, as well as the imaginary circling sharks. In physiological terms, breath-hold diving is progressive asphyxiation. It is possible because of a profound suppression of metabolism: it changes the way your body functions. Surfacing after a prolonged dive, you are not the same person: your body has moved through dramatic changes, you have been to a place where few venture. If much life is lived on the surface of things, freediving lets you plunge beneath that surface. Freediving has led me to an understanding of the paradoxical joy of being close to death: the compassion and peace.

I have lived much of my life feeling marginal, feeling like an imposter in my jobs: I expect rejection, a predictable outcome of two parents sequentially leaving when I was young. Only recently have I begun to understand that there might be strengths in those places on the margin. Freediving alone, freediving actually free of all that positivist framing and safety paraphernalia and other people, brought me back to my father’s death. He had become more and more marginal to what the world considers important, and eventually, alone, stepped off that edge, stepped free of all that judgement and demand. There is no possibility of answers once that boundary is crossed. Alone, immersed in the spaces of the silent water, I am maybe learning to let go of the questions.

In blue water diving most life is not visible, for most large sea creatures live in shallower waters. In deep blue water the freediver is exposed in every direction, completely vulnerable. That vast continuous space, that absence, is an entry, an opening. Empty space is open to anyone, an invitation. Can I live without trying to fill the silences and empty spaces? Can I learn to live in these silences and spaces? In the extraordinary emptied bliss at the end of a yoga session, when my teachers cup their hands over my ears in the penultimate position of savasana (appropriately, the corpse pose), the muted roar of the ocean fills the silence: the tides of salt blood pulsing through my body. It feels like the hand of god.

One of my teachers in Bali urged us to swim on the shallow reef before the deep water, observing and learning local marine species and ecologies, as well as being in the sea generally: ‘you need to spend time in the ocean, make it your friend’.

Freedivers in Bali (photograph courtesy of Michael Adams)

Freedivers in Bali (photograph courtesy of Michael Adams)

We become familiar with one turtle that seems always to be found in the same patch of reef, we know the batfish are curious and often come to investigate us in the deep water, we begin to understand the diurnal patterns of changing activities and species across an undersea topography that becomes familiar. And fundamentally we engage with the saltwater itself: we taste it, swallow it, rinse it through our sinuses, feel it flow across our skin – it is both all around us and within us. The tears in our eyes, the sweat on our skin, the blood in our veins, arteries, organs, have the same salt concentration as ancient oceans, reflecting the time when the ocean water itself served as the fluid transport in the bodies of our biological ancestors.

Deep in the ocean’s embrace, on one breath, feeling your mind and body change, freediving is a transformational encounter. Like all of life, it is a journey between two breaths, the first breath of life and the last breath before death, the last breath before immersion and the first breath of surfacing again into air. In yoga and meditation, practitioners speak of ‘resting in the space between breaths’. In marine mammal physiology, researchers describe the way seals will drift underwater, not swimming, not breathing, not hunting – resting in the space between breaths. On this blue pathway, naked of technology, with just one breath, the freediver’s unshielded body is open to the silent sea. The transformative encounter connects the World Ocean to the ocean within, bringing us home to the cycles of how we are born and die alone and together on this planet.

Thanks to William Shakespeare, Herman Melville, Joseph Conrad, Simone Weil, Tim Winton, Nam Le, the octopus and seal researchers, my many teachers, my various first readers, my family, the Bundanon Trust, and all the humans and non-humans with whom we share the seas.

Michael Adams teaches and researches in Geography at the University of Wollongong, and before that worked for environment NGOs, the national parks service, and Aboriginal organisations. His focus is on human–nature relationships, especially with Indigenous and local communities, and he likes full-immersion methodologies. He writes in a variety of forms, including narrative non- fiction and peer-reviewed academic articles.

The Calibre Essay Prize, created in 2007, is Australia’s premier essay prize. Originally sponsored by Copyright Agency (through its Cultural Fund), Calibre is now funded by Australian Book Review. Here we gratefully acknowledge the generous support of ABR Patron and Chair, Mr Colin Golvan QC.

I had been a writer and editor at school and university, I’d worked in the Whitlam government, I’d been a freelance journalist, and I was interested in politics, history, books, and writing, so it was a natural progression – though I didn’t realise it at the time.

I had been a writer and editor at school and university, I’d worked in the Whitlam government, I’d been a freelance journalist, and I was interested in politics, history, books, and writing, so it was a natural progression – though I didn’t realise it at the time.

Ones who write memorably, whose language combines critical acuity with verve. I could name many, but Robert Hughes, Peter Porter, Kerryn Goldsworthy, and Brian Matthews are four Australians critics I read and reread, and from whom I have learned much, even when I’ve disagreed with, or been provoked by, them.

Ones who write memorably, whose language combines critical acuity with verve. I could name many, but Robert Hughes, Peter Porter, Kerryn Goldsworthy, and Brian Matthews are four Australians critics I read and reread, and from whom I have learned much, even when I’ve disagreed with, or been provoked by, them.