- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Custom Article Title: Delys Bird reviews 'Like Nothing on this Earth: A literary history of the wheatbelt' by Tony Hughes-d’Aeth

- Review Article: Yes

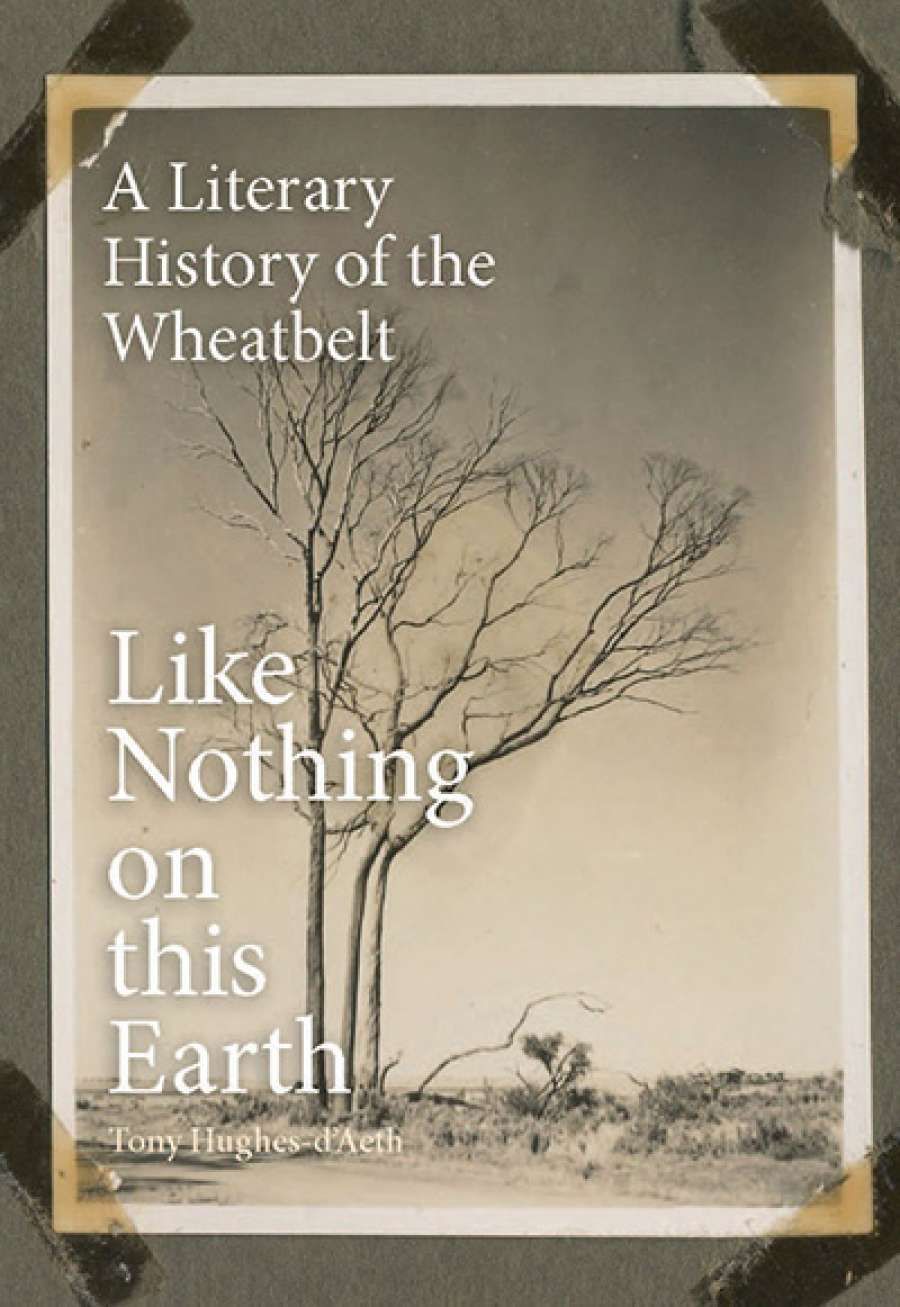

- Book 1 Title: Like Nothing on this Earth

- Book 1 Subtitle: A literary history of the wheatbelt

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $49.99 pb, 608 pp, 9781742589244

To read the work of his wheatbelt writers, Hughes-d’Aeth uses an ‘event/witness’ model. The ‘creation of the wheatbelt is the event’, and the writers are its witnesses. All of them, with one exception, have lived in the wheatbelt; some were born there; several worked there intermittently; others farmed the land, and the chapters on each of these eleven writers begin with brief biographical details. The first three – Albert Facey (1894–1982), Cyril Goode (1907–82), and James Pollard (1900–71) – are roughly contemporaneous. Although their experiences, and their writings, differ widely, each is engaged in that early essential work of manual clearing of the land, together with attempts to establish viable wheatfields. Alternating moods of hope and despair, and the effects of extreme isolation and loneliness, all emerge in the work of these three. The advent of the Great Depression drove them off the wheatbelt, signalling the end of the first phase of its development. Nevertheless, Facey’s hugely successful autobiography, A Fortunate Life (1981) projects what Hughes-d’Aeth calls ‘a moral component to the wheatbelt project’, the widely held belief that the wheatbelt offered its settlers a fresh start, deeply imbued with the ideologies of ‘goodness’ and ‘improvement’.

After a stint at one-teacher schools in the wheatbelt, J. K. Ewers returned to Perth in the 1930s and began his major work, a wheatbelt trilogy, of which only the first two novels were published. Peter Cowan, not much younger than Ewers, is vastly different both in his experience of the area (it is now a ‘post-pioneer era’) and in his writing, which signals the beginnings of an environmental consciousness. Cowan apprehends the wheatbelt as a literary region; for him ‘regionalism is something the Australian novel needs’. In Cowan’s spare, modernist stories, the wheatbelt is an existential place, ‘characterised by silence and menace’.

In these ways, Cowan is seen as the ‘first modern writer of the wheatbelt’, followed by the very modern Dorothy Hewett, for whom it was her family home. Class and race are defining factors in Hewett’s wheatbelt writing, differentiating it from that of the earlier writers, as does the range and formal amplitude of her work. Hewett’s wheatbelt becomes, for the first time, a tragic, contested place, that history traced in her epic poem ‘Legend of the Green Country’ (1966) and the play The Man From Mukinupin (1979).

Jack Davis, poet, dramatist, and activist, is a ‘pivotal figure’ who ‘introduced Noongar language [and culture] into European theatre’. His writing depicts the appalling consequences of the creation of the wheatbelt for his people, who were forced off their land into depleted, marginal existences. In zoologist Barbara York Main’s two major works, she recognises not just the loss of a ‘natural’ world, a complex ecosystem which cultivation has destroyed, but also the difference in land use of the Noongar inhabitants and the settlers who transformed the area.

A steam locomotive hauling the first train of bulk wheat in Western Australia, 1931 (Rail Heritage WA, via Wikimedia Commons)

A steam locomotive hauling the first train of bulk wheat in Western Australia, 1931 (Rail Heritage WA, via Wikimedia Commons)

Elizabeth Jolley’s The Well (1986) is the best-known novel of the wheatbelt, which in her writing, becomes a symbolic place, known simply as ‘the wheat’, silent, endless, engendering both contemplation and fear, a place of primal fantasy. Oceana Fine (1989), Tom Flood’s single, early, neglected, prize-winning novel opens with Finn, a student holiday wheatbin worker. Travelling to the wheatfield, he is motivated by a desire ‘to see if I could find something in the country. In nature.’ Rex Cleaver, head of a wheatbelt dynasty, denies him that hope, one common to much wheatbelt literature, and voices the material, capitalist triumph of the wheatbelt: ‘There’s nothing natural out there, boy. It’s a city of wheat.’

As similar preoccupations in the work of these very different writers become apparent, apparent too are the effects of social and historical shifts, notably an increasing awareness of the costs of the creation of the wheatbelt. John Kinsella’s prolific output documents a place where ‘ancient ecosystems have been shattered’, one which was formerly a ‘marvellously intricate living world’, that included the ‘lifeways of the Noongar’. Kinsella’s development of his ‘counter-pastoral’ poetic mode, and his major reputation, make him an important witness of the degradation he writes about.

A brief review can only indicate the richness of this book and the reach of its ideas. As Tony Hughes-d’Aeth notes, the ‘event’ of the wheatbelt, understood in relation to deep time, is momentary. Yet the consequences of those brief one hundred years are vast. Hughes-d’Aeth acknowledges the importance of the wheatbelt for the economic life of its inhabitants and the country, yet mourns what has disappeared. He ends with a plea for the future, using York Main’s words: ‘Our goal now ... is to reshape such [wheatbelt] landscapes so that they both satisfy our physical needs (through ... agriculture) and reflect our spiritual visions (which must surely encompass nature conservation ...)’.

Comments powered by CComment