- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

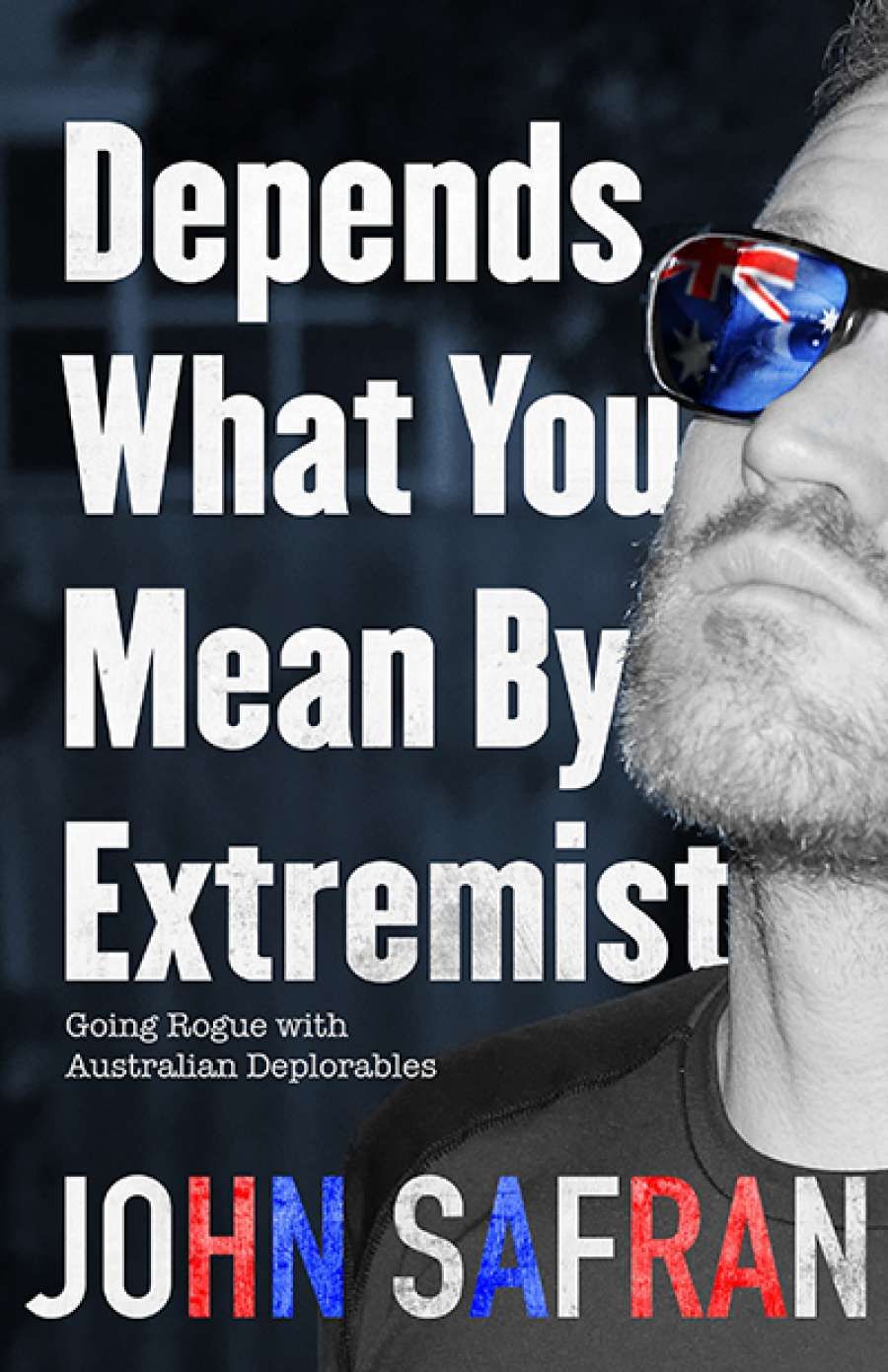

- Custom Article Title: Johanna Leggatt reviews 'Depends What You Mean By Extremist: Going rogue with Australian deplorables' by John Safran

- Book 1 Title: Depends What You Mean By Extremist

- Book 1 Subtitle: Going rogue with Australian deplorables

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $34.99 pb, 287 pp, 9781926428772

The far right, Safran discovers, is a motley bunch of crusaders and malcontents: Christian evangelicals, national socialists, and white blokes from the burbs. Safran spends time with a far-right preacher, Daniel Nalliah, from the Catch the Fire Ministries, who is also a Sri Lankan immigrant. Nalliah supports migrants, he says, as long as they assimilate and he preaches this message to his largely African, Asian, and Indian supporters. Safran is astounded by the ethnic diversity of the far-right movement, and notes wryly that left-leaning arts organisations in Melbourne would kill for such a pot-pourri of ethnicity. The bald contradictions, the gap between the banners, and the outer-suburban lives, shock and delight Safran. He meets the chairman of the anti-immigration Party for Freedom, Nicholas Folkes, and his Asian immigrant wife, and is surprised to discover that one of his interviewees, a far-right patriot called Ralph Cerminara, is the son of an Italian father and an Aboriginal mother. Cerminara’s wife, for the record, is a Vietnamese immigrant. Safran can’t believe his luck.

There is a quixotic absurdity to many of Safran’s characters, which he conveys to great comic effect. Safran spends time with preacher Musa Cerantonio before he is charged over an alleged plot to take a boat to Indonesia and join the Daesh terrorist group. When Safran visits Cerantonio at his home he is a somewhat diminished figure: he lives with his mother, is obsessed with the Monty Python movies, and delights his family by making prank calls. Cerantonio considers his mother’s surfeit of owl figurines to be graven images, but he picks his battles at home.

Safran notes that successful far-right groups must cloak their hard edges in a vanilla version of patriotism. Extremist activists usually struggle to swell their ranks beyond a small coterie of keyboard warriors, but Safran argues that the UPF was able to draw one thousand-plus people to some of their rallies because they put forward leaders who resembled tough-as-nails larrikins, not the socially maladroit hermits one may associate with internet trolling and hate crimes. It is the odd paradox of attracting large numbers to a niche cause: wider support depends on not appearing too unhinged because ‘Australia doesn’t do radical’.

John Safran (image courtesy of Penguin Random House)Safran feels no more solidarity with the extreme left, whose arguments about structural and non-structural violence confound him. The anarchists explain that there is a difference between the structural violence of the far right (the bad kind that is corporate and systemic) and the non-structural violence of the far left. Safran is unconvinced.

John Safran (image courtesy of Penguin Random House)Safran feels no more solidarity with the extreme left, whose arguments about structural and non-structural violence confound him. The anarchists explain that there is a difference between the structural violence of the far right (the bad kind that is corporate and systemic) and the non-structural violence of the far left. Safran is unconvinced.

Predictably, Safran’s Jewish identity, and the way it brushes up against the activists’ worldview, plays a large role in the book. He is called a Jewish parasite at one of his first rallies, and he is under-standably concerned by the potential for neo-Nazis to attach themselves to nativist movements. The UPF leader, Blair Cottrell, says he is not a neo-Nazi, while maintaining that every classroom should display a picture of Adolf Hitler and every child should receive a copy of Mein Kampf. Safran receives an abusive Facebook message warning him that he will feel the wrath of God. He is reading Flags over the Warsaw Ghetto: The untold story of the Warsaw ghetto uprising (2011) about the 1943 ghetto resistance, and he begins to carry a knife in his pocket. He, too, fears he is being radicalised.

Context and narrative exposition is the Achilles heel of this otherwise assured study. The reader learns of the fringe characters only as Safran messages and tweets them, and there is no sense of him pulling back to reflect, collate, and ruminate; no introductory discourse to set the scene. He moves between far-right rallies, anarchists meetings, and chats with rabbis, and we feel the loss of perspective keenly. On the other hand, investigating a movement’s underbelly and trailing his subjects is Safran’s patented style. The credibility of the book, its cultural heft, depends on how much the reader trusts Safran’s ability to draw an accurate rendering from his subjective account and, indeed, how much one enjoys his idiosyncratic company.

Comments powered by CComment