- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Custom Article Title: Paul Hetherington reviews 'Some Things to Place in a Coffin' by Bill Manhire

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

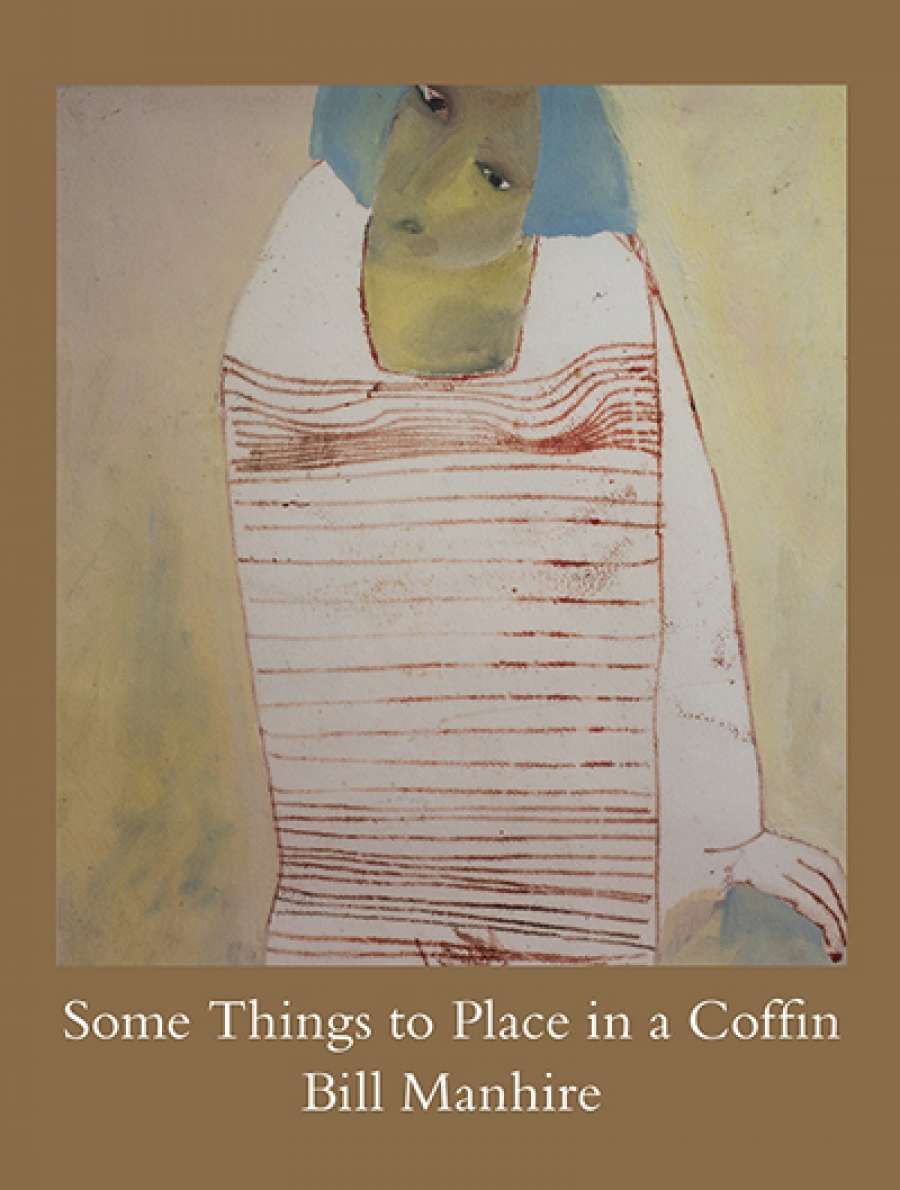

- Book 1 Title: Some Things to Place in a Coffin

- Book 1 Biblio: Victoria University Press, $25 pb, 95 pp, 9781776561056

Further poems explore a wide range of topics: a Mao impersonator who stares ‘at invisible things’; an idea of an unspecified ‘enemy’ that will take away ‘this world that you once woke into’; and a ‘survivor’ who reflects that ‘We will never sit in such places again’. Manhire conjures childhood and allies it to preoccupations with entropy and change. For example, a school bus becomes emblematic not only of the past, but of what is troubling, irretrievable, and incompletely understood: ‘The heart can hardly stay. The heart implodes / The body gets down and walks across a field.’ This is a verbal dance around the impossibility of making secure meaning out of shifting and friable memory. This theme of being alienated from crucial aspects of past experience is given a different emphasis in one sequence, where the speaker fails to ‘reach’ the ‘beautiful world’, a place of childhood, imagination, and literature rather than the real: ‘It was not the trees. / It was somewhere beyond the trees. / It was not the window or the lake.’ The sister of this poem’s speaker seems to be missing and ‘So much cold came out of the earth, / we could not talk about it.’

Other poems are wry or ironic. For instance, ‘Coastal Farewell’, comments on its depiction of parting lovers as ‘like some ancient Chinese poem / from the something-or-other Dynasty’. A number of poems are not fully explained, as if language is unable to reveal the meanings that attend to certain ideas and events. An example is ‘Learning’, where the ‘other language’ is ‘all zigzags and bad decisions’ and where ‘For a moment the raft / is reachable, then it isn’t.’

A sequence of poems, ‘Known Unto God’, commissioned for the centenary of the Battle of the Somme, memorialises unknown New Zealand soldiers killed in World War I, along with more recent refugees. There is a sheet of black paper before this section of the book, and war’s carnage is evoked by small, pointed evocations: ‘Once I was small bones / in my mother’s body / just taking a nap. / Now my feet can’t find the sap.’ This writing emphasises the way individuals are trapped within warfare’s larger movements, unable to escape or control it, their destinies sometimes made by hideous happenstance. Manhire, exhibiting great tonal control, refuses to be maudlin. The poems suggest that while language may memorialise, it can only gesture glancingly at war’s horror.

A contrasting group of poems makes use of various song-like gestures, conjuring a poetic world where serious themes – such as ‘The end of empire is a special emptiness’ – are framed by more popular tropes. Later poems take up a wider variety of references, one beginning with a line by W.B. Yeats, another satirising the idea of a politician’s election address, and a further example playing teasingly with the notion of autobiography. A poignant group of prose poems probes memory failure, questioning ‘what will last?’ in our lives and culture.

Bill Manhire (photograph by Grant Maiden)

Bill Manhire (photograph by Grant Maiden)

The volume’s title poem remembers the painter Ralph Hotere, a reproduction of whose painting Untitled (c.1971) is on the book’s cover. This one-page work conveys a sense of a whole life by listing the kinds of things the poet imagines placing in his friend’s coffin. The diversity of suggestions is beguiling, sometimes surprising, even quixotic: ‘Some Lorca, some lacquer. / A fishing rod. A hammer. / The dog Matiu. / Timber & bricks. A Tiger Moth. / Some rope, some sky, some ocean.’

The volume concludes with a sequence entitled ‘Falseweed’, which is simultaneously about the environment and the struggle to make poems – and thus, ‘to take flight’. There is also a kind of poetic coda, in which the speaker states, ‘I was defeated, done with speaking’, again negotiating the space of the ineffable.

Many of this volume’s poems are constructed as spare statements that are sometimes tenuously connected. The emphasis is on missed connections as much as on a coherent whole – which is an appropriate way to approach what is lost or hardly known. For Manhire, the beautiful world is an ungraspable place, but his gestures at naming it – however incomplete – are finely conceived and salutary.

Comments powered by CComment