Drone

Someone says drone and I see the cell phone it tracks, see the hand holding the cell phone

Being tracked by the drone, see the arm connected to the hand holding the cell phone

Being tracked by the drone, see the shoulder manoeuvring the arm connected to the hand

Holding the cell phone being tracked by the drone, see the person attached to the shoulder

Manoeuvring the arm connected to the hand holding the cell phone being tracked by the drone,

See the people attached to the person holding the cell phone, attached by proximity,

By love, perhaps, respect, maybe duty, and the person I see is unseen to the drone and unseen

By the drone, is not seen even by the cell phone held by the unseen, who does not see himself

As the unseen while being tracked by the drone, seeing only the length of his arm and the hand

attached to the arm holding the cell phone being tracked by the unseen drone.

Someone says drone and I see the hand that pushes the button – or flips the switch, maybe –

See the arm connected to the hand that pushes the button – or flips the switch, maybe –

See the shoulder manoeuvring the arm connected to the hand that pushes the button –

Or flips the switch, maybe – see the person attached to the shoulder manoeuvring the arm

Connected to the hand that pushes the button – or flips the switch, maybe – of the drone.

And the person I see is unseen to the drone and unseen by the drone, is not seen

Even by the button or the switch held by the unseen, who does not see himself as unseen.

Someone says drone and I see two hands gripping their devices in the grip of each other

Each hand convinced that it’s the hand that holds the truth.

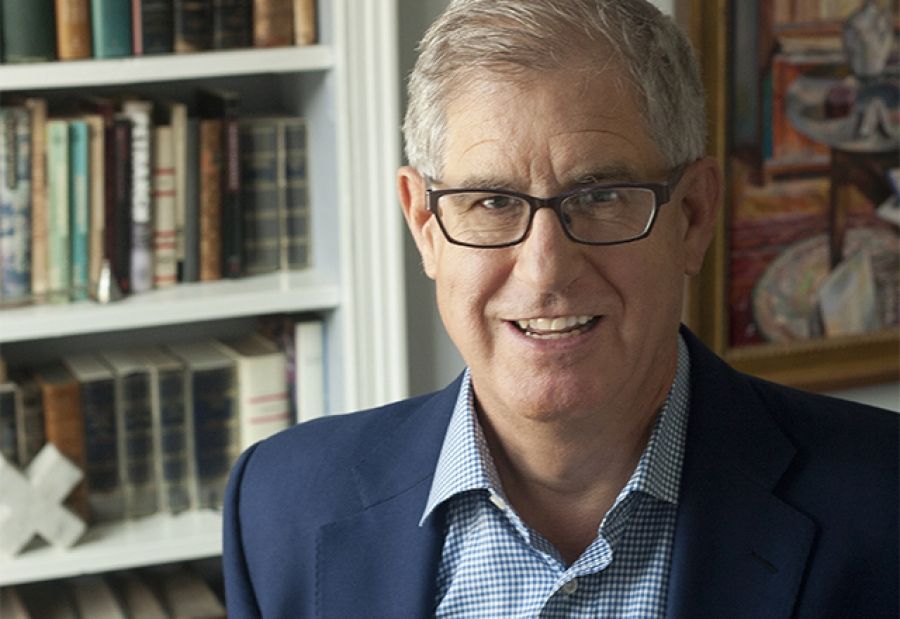

Michael Lee Phillips

Four Egrets

Four white egrets perch on four baby citrus trees

at the four corners of the world and you wouldn’t

see this if you were not told to look. Their black

eyes stare at the drying canal and stave hunger

for snail and frog and minnow because those remains

are not more than sinew or bone in cracking mud.

The two llamas and two horses in the chain-linked

front yard, the one tree in that yard that has been

stripped of bark and leaves, the four of them eating

hay that has been spread across cement – you would

not share their thirst at the moment you hope

for rain to fall on your dusty truck because you see

them everyday and their backs are not your dusty

truck. You wouldn’t see the barn buried under piles

of hardwood vine stakes or wonder what is inside

the barn in the no-light – you would not, before

it’s gone. And what about the distribution of bee

corpses from your windshield into fine dust under

the few wilted melons near goathead thorns? The hard

and tiny horns may stick to your boot and you must

shake them loose after stepping back into the truck

after taking a picture of the patch of weeds near sun-

bleached powder that streams across the upward face

of the asphaltic chipseal – and further out, you may

see the glint of shimmering mylar balloons that

have released their helium and have set themselves

softly down, like dropped testicles, displaying bright

round words that announce happy birthday or over

the hill and you would not remember what day

it was when you decided to try to be someone else

between shifts, between each appearance of your-

self embedded in the structures of everything but you.

Ronald Dzerigian

The Snow Lies Deep

the low fish

the late violin

the dreaming wolf

the mistletoe

the firefly

the favoured child

the favourite child

the deepwater fish

the comet fly-by

the tuned violin

the missed toes

the dreaming wolf

a dream of wolves

afraid child

missing fingers & toes

poison blowfish

clown’s violin

swarming fireflies

warning fire lights

screaming wolves

lowly violinist

flailing child

dreaming deep fish

kissing mistletoe

kissing missed you

firefly alights

deep sea fish flight

howling wolf rites

dreaming low child

flighty violin bow

low note violin

falling mistletoe

sleeping snowchild

darkened firefly

woken old wolf

cloud of flying fish

fireflies light the child’s way through the town

benthic fish gulp mistletoe berries down

last known wolf tracks violin-playing clown

and the snow lies deep all around, all around.

Jen Saunders

Laika

I’d spent the morning on the coast

where I’d gone to be away from you

and by extension, myself, the tabula rasa

of the sky interrupted by ravens

that had made of themselves a raised

felt collage in the shade. A kite surfer

was belting through the swell, too far

from shore for me to read the maker’s

name on the sail, but close enough

to see the line she was leaving in dark

green shelving like a fast download bar.

I climbed a headland to see where

I’d been, yet all but one compass point

seemed defined by the decisions

we’d made together, and even that

was swinging between hard south,

where we’d met, and our last night –

a nor’wester blowing itself out

like a trial separation. I walked to lose

the sound of us having another shot,

giving it our best. Cutting through

littoral scrub, bearded dragons,

like offcuts of distressed leather,

stared from lantana and twisted trees

the wind had cut back and down.

I crossed a road where luminous cable

was being unspooled, rolled out,

the national broadband like a cannula,

force-fed to the collective interface.

I went off the track, unpicking myself

from honey locust thorns. In a clearing

I lay down to watch husks of old blood

vessels bubble-chain across the sky.

You were out of range and reach,

like the retreating tag-end on a length

of rope at the stern of a listing lifeboat

taking on water. When I said your name,

a treecreeper quipped that distance

and wistfulness are all we need,

when healing. Starting back, with dusk

on the make and bits of moon

like stopgap animation through leaves,

I found a tin crate, broken at the welds

by impact. Inside, surrounded by glass,

the skeleton of a dog. I thought

of our kelpie from Working Dog Rescue,

her love of balls, her going back

and around a gull flock she’d follow

down the beach. She was killed

when a jet ski doubled back on its wake

as she was closing in on a stick.

I knelt beside the crate. I considered

the flight of Laika, the astronaut dog,

shuttled into obituary. A scattering

of bones and glass in a beaten tin box

as if she’d been satellite-tagged

and released, already deceased, to burn out

on re-entry and go to ground in the bush.

It was raining as I reached the road,

the lights of houses being turned off

and on by windy trees. I found the beach

gone under foam to the tideline.

It was there we had talked about how

to read the ocean, to find the direction

of a rip in a gutter. You said panic kills

more people than limited swimming skills.

I stripped and stood in the shore break

between the over and the underworld,

the afterwards and the as it was, listening

to the slurred pillow talk of the tide.

Your face appeared, your features

like a steady fall in barometric pressure,

like memory loss where the hard drive

of the sea crashes in to be erased.

Anthony Lawrence

and it is what it is

Chapter 1

You are given fingers before a mouth. Your ears are the last to form.

What comes next becomes what I am most afraid of –

I wonder where that wilderness in you was born.

Yesterday, they called me on the landline,

asked for my date of birth and nationality;

fourteen, zero six, thirty nine, China.

Nobody tells you to keep your hands

tied behind your back and they need to stay behind your back

they need to stay, they really need to stay.

Chapter 2

I want to cut something, I need,

I need the certainty of a clear division.

A binary, a slip, a something to keep my hands behind my back.

You write long letters about the man in there

who springs overnight.

There is nothing I can do, I swear it, there is nothing I can do.

They told me to tell you not to fight it

when it comes because when it comes it will rupture your

vocal cords, you will bend your knees.

I keep photos of us to compensate for your memory loss

though now when I hold them, they feel like slices of seconds from

someone else’s life, a life I push outside of myself, a life I have no care for.

Chapter 3

I told you so, I said that none of this would matter,

the clocks on your face would lend itself to surrender

and in the end it will all feel like a dream, a deep sleep dream.

I wake to find markings on my forearms, markings

raised like welts and I wonder whether it came from the

thrashing in your sleep or if I had lived some other life, become some other person

when consciousness slipped away, ashamed by its own watchman.

They told me to tell you to close your eyes

turn the self-immured blindness into a sea

imagine the arms of her insidious pull weave its web of comforting tunes.

You will feel less if you let it run through you

let the synapses burn through your wild river, and I will

start to tell you, to

neglect the parsimonious man in you.

Chapter 4

You take years to settle onto the ocean floor,

spread your skin like particles of dust,

entering the chain of subsistence they call

evolution, though I knew for one moment.

They cannot hide you behind their panoply

crust, gammon, imperviousness,

all at once it seemed impossible

But again the seismic undergrowth of something

I cannot see, something like a light I cannot extinguish.

You put words into my mouth now.

Stop.

You need to stop putting words into my mouth.

Jessie Tu

Sentence to Lilacs

‘And that great black hole where a moon ago I wanted to drown

It is there I will now fish.’

- Aimé Césaire

Europe, stolen schoolgirl, she

radishes on the fresh

water creek

snow on wheat ... I mean

no, don’t help me ... no, don’t help ...

I have that lisp.

So I pitched my tent in the hotel lobby

chiselling pegs into tiles until they burst

like chalk under a hammer, wanting to sleep

though no one taught me how

Her stutter

Her personal pronoun we

Her stutter

And she leaves me

To the imagination

Stuttering a way of stressing

Her point

We’re not history’s country.

I was driving among the mangroves

in the photo. I was zipped-up, galoshes

on pushing through swamp to watch

the bird-watchers in the photo. I was

watching them watch the distant marsh

terns and dusky-moor hens. In the photo

cockatoos scream as if the sky itself has split

from joy, though it’s hard to tell from the

When I wake on tiles the sky

I remember taking interest in

like a tourist

the sky

being gone soon anyway

When I wake on tiles and clouds

in long procession

like battles

no one cares

When I wake on tiles reading War and

War is, you might say, unknown to us

our humanity never

questioned

To us the sky’s the question

that can beg all it wants

and Peace, that bit when

I’m not racist but the sky

and Prince Andrey

Waking on tiles

on a killingfield

seeing only the sky.

Its infinite

I can’t believe you’ve never heard of

I was driving through country-towns photos

of closed-down milk-bar convenience stores

hung on the bare walls of a private gallery

driving, slowing, at the boomgates a dog

tethered to a stump, unbegrudging

another day I’d sleep at the wheel

though no one taught me how another day

I’d drive through country towns just

to watch the cowpats basking in the sun

knowing I still own the word

deciduous.

Others might use it but they

don’t know how to pronounce

the silence.

Louis Klee

pH

14 Sodium Hydroxide Washed out:

the unbalanced washing machine

jitters and grinds across the laundry

choking on business shirts.

13 Bleach Someone has poured bleach

over the evening.

We can’t stand ourselves.

We raw and rub

and exsanguinate into silence.

12 Ammonia A rainbowed slip of chemicals

wrinkles and cakes in an onshore breeze

against the east side of the island.

They will trace it to a container ship

bound for Singapore.

11 Charcoal She left the church early this morning,

blinking and red-eyed.

It’s too soon for Amazing Grace.

That song rolled into the furnace with a coffin.

10 Soap Only losers are prosecuted for war crimes.

The foreign correspondent footnotes

chemicals blistering in a child’s eyes, and

barrel bombs germinating in Syria.

Skin doesn’t remain neutral.

9 Baking Soda Breathing through the balloon of their skin,

the Corroboree Frog

stops calling in Kosciuszko.

Stained by a fungus dust,

their skin skews and barks and peels.

8 Sea Water Human interest story: scientists weep

a solution of sodium and potassium

but can’t save them.

There is something out of balance.

7 Blood Water should be neutral,

but all day we ferried test tubes

and paper tapers bearing tell-tale colour.

The tank smears with algae.

Even the hardy, brutal goldfish

would gulp and bloat in it.

6 Milk The suncream doesn’t last.

15 Overs under the pinched membrane

of ozone that pales the sky

and we are painting ourselves again.

Itching all weekend,

the boys blister in missed lozenges of skin.

5 Black Coffee She has lost all her friends,

strained off by marriage,

tired out by children

and the local café is precious to her.

We perch studiously on the stools

sip our coffees and talk to the owner.

4 Orange Juice This is a good year for mosquitos,

burned out by the government’s careful

carpet bombing of estuaries.

We can sit on the deck into the evening

and drink a haze of bitter wine.

Something in the strafing chemicals attacks bees.

Next year will be bad for crops.

3 Coke In the machinery of God

100 billion people have lived and died.

The experiment must be nearly done.

2 Vinegar Most days the river runs white

downstream from the mine.

The bunds have leaked for years,

the seepage pits are full.

It’s a fragile balance when

the island’s economy depends upon that silver.

The earth eats itself.

1 Battery Acid We rarely kiss

and even less on the lips.

My lips are an acid etch.

She leaves at different hours

and numbs her way to work.

There is something out of balance.

Damen O'Brien

More

More