- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Custom Article Title: Gig Ryan reviews 'The Green Bell' by Paula Keogh

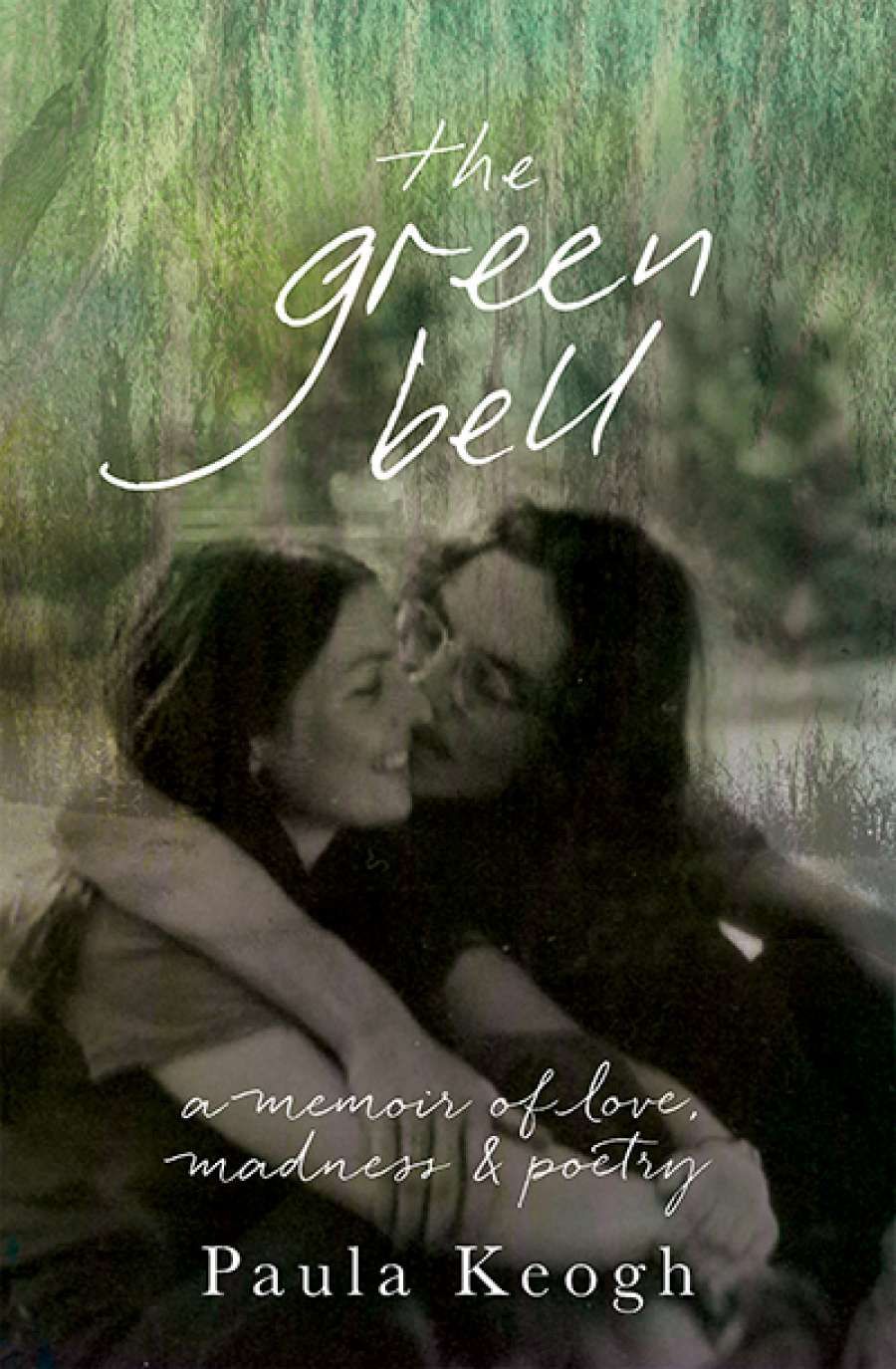

- Book 1 Title: The Green Bell

- Book 1 Biblio: Affirm Press $29.99 pb, 288 pp, 9781925475524

Keogh depicts the poet as tenderly in love, but soon after also as the cause of more pain for her because of his casual infidelities. Here, Dransfield is a young madcap befriending the inmates, not just the intellectual puzzle of earlier studies or the ‘heightened’ modernist kindling postmodernist poetry that Kinsella posits. Keogh captures well the intensity of love, ‘a glow worm in a cave of bats’, that colours all the young couple sees and fills them with audacious plans, but she has a queasily naïve concept of ‘the poet’, and by the book’s end her view is only slightly more coolly assessed. Dransfield was both the charming personality she sees through a lover’s eyes as well as an exploitative careerist and real-estate speculator.

Keogh’s search for authenticity and her desire to quieten the noises in her head (first manifested when she was a bereaved teenager) takes her to asylums of various kinds, then in turn to ‘recreational’ drug use, communal living, marriage and a child, an ashram, psychotherapy, and finally to further university studies. These quests are clichés of the 1960s generation, but each generation quests for authenticity of its own, and for Keogh these are not only sincere but necessary to anchor her to reality, and to understand, and thus avoid, the traumas of instability: agonisingly, she receives news of Dransfield’s death only after his funeral. Yet much of her life post-Dransfield is perfunctorily noted. At times her insights are profound, but much of her trajectory through life is summarised in simple statements that can seem drably unexamined.

Paula KeoghBy book’s end, Keogh has reached a truce with her past selves, but there is little perception of Dransfield that could not also be imagined from his work. The glamorised view she has of her first love, ‘the golden-winged god, hovering close’, can never be entirely discarded. There is cursory understanding that much of his behaviour, as well as being sexist, was drug-affected or typical of many young artists, though Dransfield’s self-mythologising and property ventures were probably exceptional. The few poets Keogh meets through Dransfield are mostly the older father figures and mentors he flattered and teased, rather than less gullible contemporaries such as Nigel Roberts, John Tranter, or Vicki Viidikas. Many contemporaries view him as an ‘arch-fabricator’ and ‘romantic bullshit-artist’, as Pam Brown has written, rather than a poet displaying the hint of ‘genius’ that some poets wished to indulge. In short he was, like everyone, full of contradictions. Ultimately, and thankfully, it is the poems that matter.

Paula KeoghBy book’s end, Keogh has reached a truce with her past selves, but there is little perception of Dransfield that could not also be imagined from his work. The glamorised view she has of her first love, ‘the golden-winged god, hovering close’, can never be entirely discarded. There is cursory understanding that much of his behaviour, as well as being sexist, was drug-affected or typical of many young artists, though Dransfield’s self-mythologising and property ventures were probably exceptional. The few poets Keogh meets through Dransfield are mostly the older father figures and mentors he flattered and teased, rather than less gullible contemporaries such as Nigel Roberts, John Tranter, or Vicki Viidikas. Many contemporaries view him as an ‘arch-fabricator’ and ‘romantic bullshit-artist’, as Pam Brown has written, rather than a poet displaying the hint of ‘genius’ that some poets wished to indulge. In short he was, like everyone, full of contradictions. Ultimately, and thankfully, it is the poems that matter.

Keogh’s post-Dransfield life may be equally worthy of interest, but because The Green Bell focuses on her short period of romance with Dransfield in his final debilitated months, one is left with the impression that the intense psychosis and turbulence of her early years, musing with Dransfield in the ‘green bell’ curtained by the willow tree’s leaves, remain the most significant parts of her life because they augur its adult awakening. ‘Moments expand into what the two of us call “round time” – the boundless space inside the green bell.’

Comments powered by CComment