- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

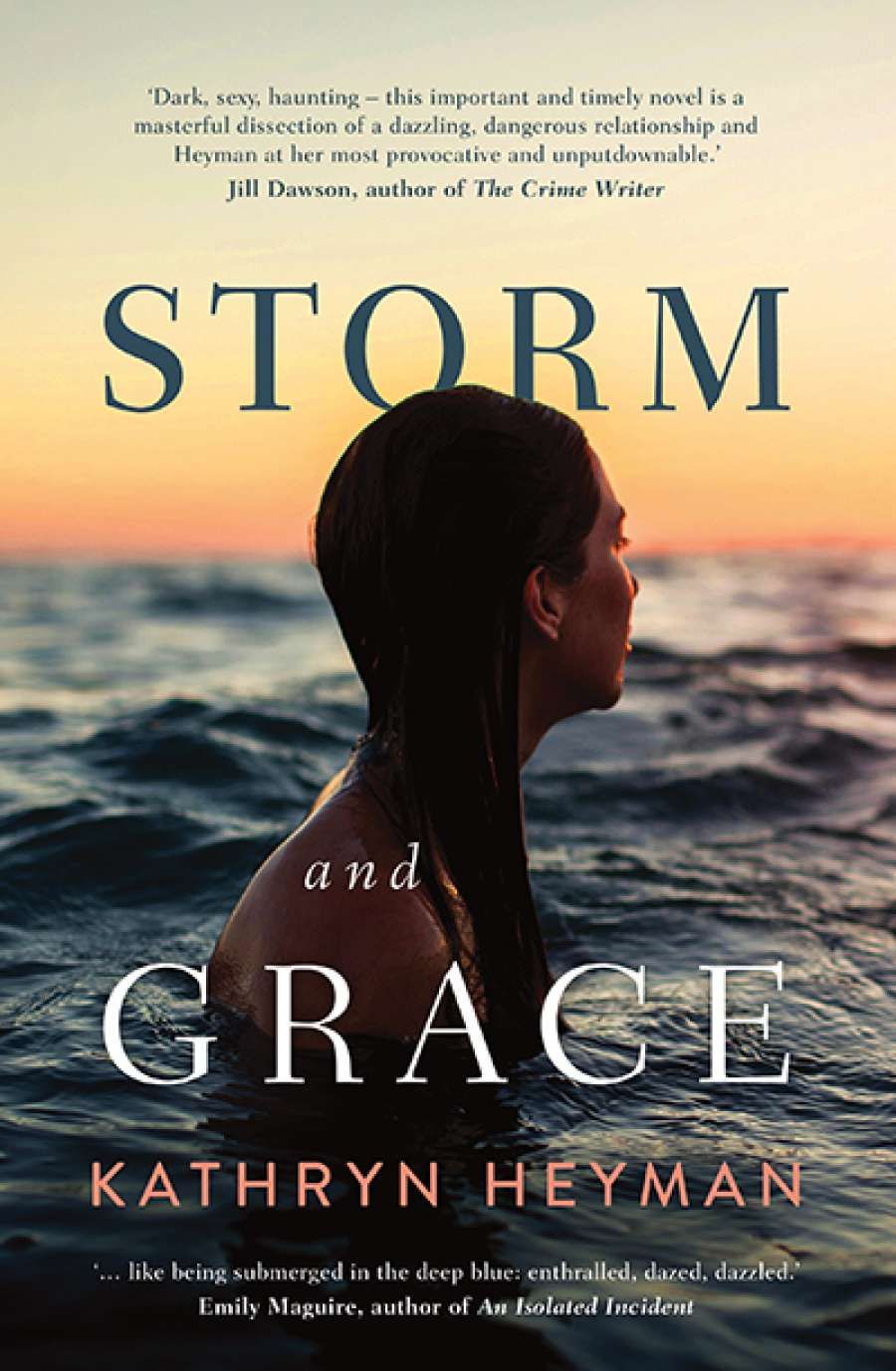

- Custom Article Title: Anna MacDonald reviews 'Storm and Grace' by Kathryn Heyman

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Kathryn Heyman’s novel, Storm and Grace, joins the recent proliferation of fiction by Australian women that deals with intimate partner violence. Like Zoë Morrison’s ...

- Book 1 Title: Storm and Grace

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin $29.99 pb, 360 pp, 9781743313633

Grace is an experienced diver but until now has always dived with a tank. Under Storm’s tutelage she learns to free dive. When his own record is threatened by another diver (‘some ginger slut’, according to Storm), he pushes Grace to deeper and more dangerous depths. Grace is all ‘perfect obedience’. In an all-too-familiar vein, she confuses pleasing Storm with loving, and being loved by, him. But there is also something in Grace that seeks out the danger of these deep, breathless dives. She has a history of self-harm. Throughout the novel there are intimations of violent sex – bruising, soreness, pleasure found in the ‘sharp brutal tang’ of pain – and, while free diving, Grace looks forward to ‘the glorious choral edge of death’. Thus, Storm and Grace is a cautionary tale. The desire for danger, for the cliff edge between life and death, is central to the threat of impending violence that colours the novel from beginning to end.

The most inventive aspect of this book is its narration. The story is told by a chorus of vengeful, Fury-like sirens, women who have suffered violently at the hands of men, and who imbue the story of Grace and Storm’s relationship with a sense of foreboding. ‘You will be unsettled,’ they tell the reader, ‘unfooted, undone. We promise you this: that until you turn ... and hear us, we will not stop. Listen ... this is the true story’:

We have been here forever, watching ... We have been thrown from balconies; we have been pushed from boats ... we have been battered with metal bars ... we have been buried in piles of dirt ... We are legion. And we will not forget.

These women lend the novel its narrative depth. Their siren song is a warning of the threat of gendered violence, but also, and perhaps most importantly, of the potentially lethal consequences of the kind of romantic love represented in this book. Grace – like all women, if we are to believe the story’s narrators – has been primed by popular culture for the ‘terrible love’ of romantic fantasy: ‘All she knew was this: adventure had called her, love had called her, and she would not say no. Who among us would say no to love? To romance? ... We’ve read the books, we’ve seen the films, we know the songs.’

Grace succumbs to the idea of romantic love such cultural products propagate. But Storm is also a dangerous fantasist. By his own telling, he is of Inuit descent, has a Turkish grandfather, an ice-diving Austrian grandmother; he is named for a storm that raged as he was baptised in the ocean; his boat (the Sedna) is called after the mythical Inuit girl who married a god and became goddess of the sea and storms. It is Storm’s intimate association with the sea that attracts Grace, who has always felt at home there. Storm sees himself as the ‘god’ the girl (Grace) has fallen in love with, and, in keeping with the tropes of romantic fantasy deplored in this novel, they both see him as Grace’s saviour. Unsurprisingly, the reality is quite different. Storm’s mother claims a more prosaic genealogy: the family hails from New Jersey and Storm was baptised James. The siren chorus, too, offers an alternative version of the Sedna myth in which, rather than marrying willingly, the girl is sold by her father to a man she does not love. When Grace questions Storm’s various accounts of his personal history he upbraids her for being ‘so literal’.

Kathryn Heyman (photograph by Luke Stamboulah)

Kathryn Heyman (photograph by Luke Stamboulah)

Heyman’s novel borrows from romance literature in order to critique it. As a result, the dialogue between Storm and Grace can be excruciating: ‘“I’m supposed to be interviewing you.” Weakly, she tried to grasp the memory of her task ... “They shouldn’t send such charming mermaids to do the interviews if they don’t want their subjects to fall in love.”’ Likewise, Grace’s initial, virginal naïveté can be difficult to fathom. However, little is to be gained from an overly literal reading of Storm and Grace, which should be read as employing such tropes in order to expose them for what they are: dangerous harbingers of terrible love.

Comments powered by CComment