- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

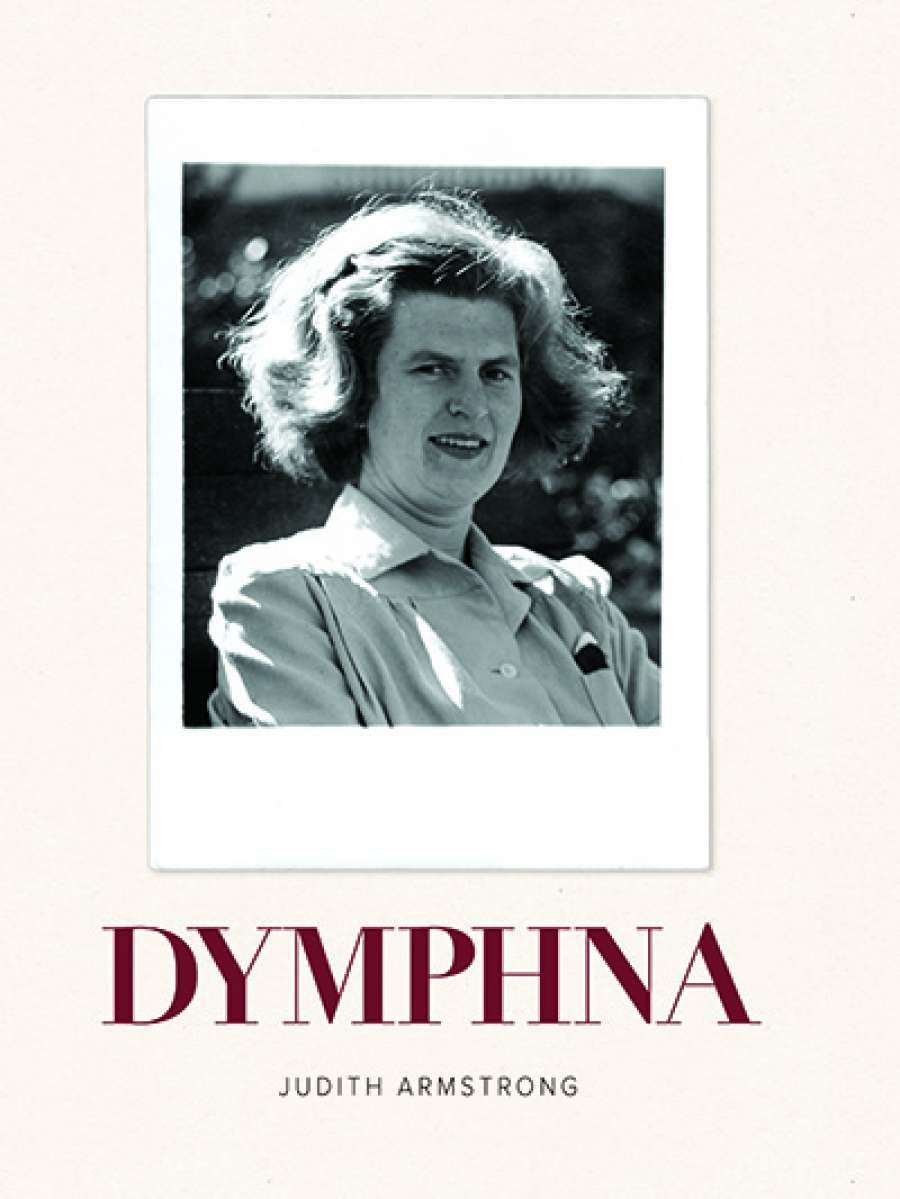

- Custom Article Title: Brian Matthews reviews 'Dymphna' by Judith Armstrong

- Book 1 Title: Dymphna

- Book 1 Biblio: Australian Scholarly Publishing, $39.95 hb, 202 pp, 9781925333657

In ensuing years, however, both Glendinning and Motion also began to doubt, Glendinning rejecting what she came to see as the ‘kind of authoritative tone that reckons to give you the whole picture of somebody’s life’, the tone, that is, of conventional biography; and Motion joining the ranks of the apostates to suggest that ‘if [biography is] only pursued by orthodox means, it will endlessly go round the same small wheels of people who left papers behind that we can re-read and re-interpret’.

Motion’s doubts and worries about biography were brought to a head when he began to write Wainewright the Poisoner (2000). Confronted by the impossibility of constructing a ‘complete linear life’, Motion came to a conclusion that would have been anathema to him and his compatriot in Adelaide in 1988. ‘Well,’ he resolved, ‘I’m going to have to make it up.’

In seeking to ‘rescue’ Dymphna Lodewyckx ‘from her reputation as a woman of talent sacrificed on the altar of matrimony’, Judith Armstrong faces some of the problems that bedevilled Andrew Motion. Although she doesn’t ‘make it up’ (neither, strictly, did Motion), she espouses a Hilary Mantel-style of ‘biographical fiction ... serious scholarship ... leavened by imaginative departures such as made-up conversations’. Conversations, however, exist in a context of personal encounters. Their timbre and tenor will influence how the speakers appear to a reader, so ‘making them up’ becomes a sensitive biographical manoeuvre. Likewise, the range, profundity, and power of the ‘imaginative departures’ will colour and influence the depiction of the ‘real life’ they have been invented to serve like one colour on a palette bleeding into and subtly transforming another.

Hilma Dymphna Lodewyckx, 1938 (National Library of Australia)Armstrong acknowledges some help from members of the Clark family and inspiration from An Eye for Eternity (2011) – Mark McKenna’s multi-award winning biography of Manning Clark (wrongly cited in the Preface as Ever Manning) – and she is in any case an experienced and accomplished research scholar. She is not writing in a vacuum, but she seems in some ways a lonely figure. There is no bibliography, there are no notes, no formal acknowledgments. Her frank and admirable detailing of her ‘Mantel approach’ tends to contribute to the sense that these are ‘untrodden ways’ (though there are several biographically innovative Australian precursors): ‘Many of the thoughts and conversations I have attributed to her cannot be traced directly to a letter or an interview but are guided by the understanding I formed of her in many ways ...’ Compare Motion in his Foreword at an equivalent moment: ‘... anyone wanting to write about Wainewright today ... would face formidable difficulties, if he or she were to use orthodox biographical methods’.

Hilma Dymphna Lodewyckx, 1938 (National Library of Australia)Armstrong acknowledges some help from members of the Clark family and inspiration from An Eye for Eternity (2011) – Mark McKenna’s multi-award winning biography of Manning Clark (wrongly cited in the Preface as Ever Manning) – and she is in any case an experienced and accomplished research scholar. She is not writing in a vacuum, but she seems in some ways a lonely figure. There is no bibliography, there are no notes, no formal acknowledgments. Her frank and admirable detailing of her ‘Mantel approach’ tends to contribute to the sense that these are ‘untrodden ways’ (though there are several biographically innovative Australian precursors): ‘Many of the thoughts and conversations I have attributed to her cannot be traced directly to a letter or an interview but are guided by the understanding I formed of her in many ways ...’ Compare Motion in his Foreword at an equivalent moment: ‘... anyone wanting to write about Wainewright today ... would face formidable difficulties, if he or she were to use orthodox biographical methods’.

Whatever Armstrong’s perceived or encountered problems, and whatever the liberties she has taken, or is seen to have taken, she has written a fine biography of a fascinating, immensely talented woman. Her ‘mission’ – to show that Dymphna was not ‘sacrificed on the altar of matrimony’ – means that the story of Dymphna’s marriage to Manning Clark must be one of her central concerns, and that story is threaded through the narrative, bringing with it some wonderful portraits and perceptions of the joys, intricacies, trials, and sacrifices involved in having and nurturing a large and growing family, as well as some sharply ironic glimpses of Manning’s self-absorption. Gradually and expertly, as things unravel, in all senses of the word, Armstrong shifts the emphasis from Dymphna as a possibly unappreciated helpmate – her own growing suspicion, as Armstrong portrays her – to Dymphna’s being recognised as a brilliant linguist, translator, public speaker, and, when required, a commanding keeper of the flame.

In a conversation which begins with Judith Wright but becomes Dymphna’s recollection of a talk with her daughter-in-law Elizabeth, Dymphna is asked if she acknowledges that she had had an interesting life. She replies, ‘Oh yes, that of course. I was quite often bored as a child, but never as a grown-up. Just miserable, frustrated, impotent. And angry ...’ It’s not clear whether this important revelation is ‘biographical fiction’, a ‘made-up’ conversation, or ‘traceable to a letter or an interview’. Which brings us tantalisingly back to Glendinning and Motion, to seemingly authoritative tones and the difficulty or impossibility of ‘orthodox biographical methods’.

Dymphna is a challenging, beautifully managed, and daring biographical adventure, and a judiciously affectionate celebration of a remarkable woman.

Comments powered by CComment