In 2008, when Patrick White’s unfinished novella The Hanging Garden was liberated from obscurity, his biographer David Marr suggested that White might have returned to this ‘masterpiece in the making’ in 1982 had he not been beguiled by the ‘siren song’ of the theatre. This is the conventional narrative: flirtation and distraction, with Patrick White, Australia’s unambiguously great novelist, being lured from his writerly fortress on Castle Hill by the soft looks of capering youths, the glamour of footlights, and the thrill of first nights.

Of this moment of discovery Marr writes: ‘sitting with the papers all around me in the National Library, I sent a message to Armfield: “I have made a great PW discovery: 50,000 words of a fine novel set on the North Shore, abandoned to write Signal Driver. I blame you.” He replied: “O fuck.”’

Is theatre White’s coast of Anthemoessa? Is it ‘a damn shame for Australian writing’, in Marr’s words, that White abandoned ‘a masterpiece in the making’ in order to write Signal Driver, the play Jim Sharman commissioned for the 1982 Adelaide Festival? Is this the great ‘O fuck’ moment of Australian letters? Perhaps. As literature, the best of White’s plays – let alone Signal Driver – struggle to hold their own against even the least of his novels. Taken as literature, the plays, all of them, though manifestly the work of a brilliant writer – that vivid poetry of desire and desperation – seem in almost every other respect unsettled, rough, and incomplete – in a word, problematic.

But the comparison is invidious. Our lust for hierarchies tends to obscure just how original White’s plays are. Whether or not they bear comparison with the novels, they are unprecedented works in Australian theatre history. It’s not just that they are the work of a twentieth-century prose master. To start with, there is the wonder of his dramatic verse. Open any of the plays and some line will catch your eye, whether blunt or beautiful, profound or appalling. Even where there are failings – and White knew there were failings – they tend to be those of the intrepid. This is not to deny that his construction and exposition can be strained or that his dialogue can stutter; it is simply to give him credit for the originality of his dramatic conceptions, and the sweat it cost him.

Besides, it is their restless, unresolved quality, beyond their basic dynamism and viability as drama and their accompanying verbal brilliance, that has made them so influential. They present staging problems that are interesting to solve. And those solutions have gone a long way to shaping a new kind of theatre in Australia, a broadly expressionistic, image-driven theatre, one that is now a potent force, even a dominant influence, in companies once considered bastions of naturalism. And it is no mere coincidence that a line of significant theatre directors and designers have drawn inspiration from them and worked to establish them in the national repertoire.

The 2012 centenary celebrations made much of White’s lifelong passion for theatre. There were many fond and forgiving tributes from directors, producers, and performers – recollections of his generosity and animosity, his enthusiasm and enmities, his disappointments and his eventual vindication. The Adelaide Festival episode was told and retold – the rejection of The Ham Funeral by the board of governors – as was its sequel twenty-eight years later: Neil Armfield’s triumphant revival of the play in 1989.

But what does it mean when we say that White had a lifelong passion for theatre? It means that he had an essentially theatrical imagination. From the first, when his mother introduced him to those ‘dark little crypts’, the amateur theatres of Sydney, White recognised his problems – romantic, existential, spiritual – as being fit problems for the stage. It’s there in the childish picaresques and melodramas he wrote as a nine-year-old, in his adolescent career as a stage-door Johnny, in his midlife ambition to be a West End dramatist, and in the flamboyant caricatures and scenic drama of even his densest and most formally complex novels.

Eight plays in all have been published. The first, The Ham Funeral, stands somewhat separate from the rest. A transitional work, it was written in 1948, at Ebury Street, London, while White was preparing to return to Sydney after twenty years living abroad. It’s a Gothic farce about a dead landlord and his lusty widow, puffed up with the high-flown yearnings of a young poet lodger. Not only a farewell to London, it is also a farewell to his old ambitions. White had received faint praise for his earnest attempts at writing commercial comedy; now he had written The Aunt’s Story, knew it was good, and could see his that future lay in Australia. The Ham Funeral is a crude thing, not without some surreal attraction, but stiff and rattling. In it we can hear the sound of one trying, as Thomas Bernhard might say, to breathe out what’s been left behind, though not yet able to breathe in something new. The play went unperformed for fourteen years, and it was fourteen years before he wrote another.

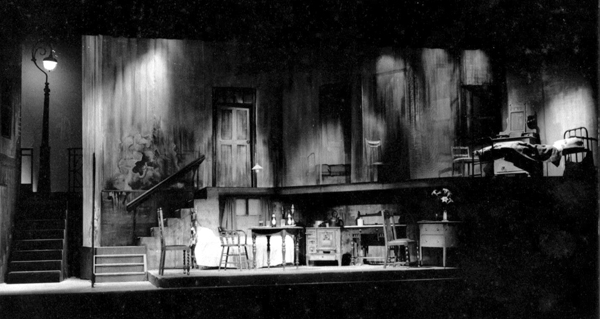

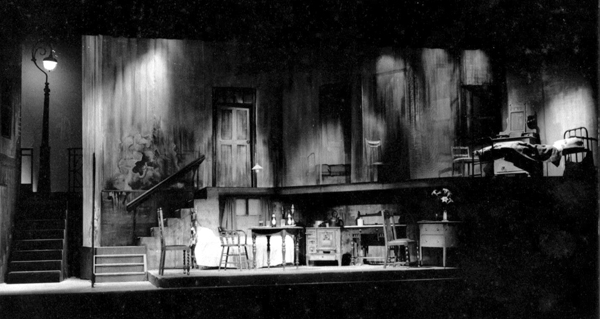

S. Ostoja-Kotkowski’s set for the world première of The Ham Funeral by Patrick White, directed by John Tasker, November 1961. (photograph by Hedley Cullen, courtesy of the University of Adelaide Archive Collection)

S. Ostoja-Kotkowski’s set for the world première of The Ham Funeral by Patrick White, directed by John Tasker, November 1961. (photograph by Hedley Cullen, courtesy of the University of Adelaide Archive Collection)

White’s satire on suburbia’s nice conformism, The Season at Sarsaparilla, written in response to the Adelaide Festival controversy, appeared in 1962, and was followed the next year by the exhibition of that elderly monster of goodness, Miss Docker in A Cheery Soul. Both plays overflow with wicked, caustic intentions but are raised up by the same spiritualist sensibility that had manifested itself in Riders in the Chariot (1961). Together they are probably White’s most ambitious and rewarding plays. In 1964, buoyed by critical success, he essayed a more classic mode with Night on Bald Mountain, which he described as ‘the first Australian tragedy’. The influence of Tennessee Williams and Eugene O’Neill hovers over the play, an addiction saga with a faintly comic twist, and there is much of Mary Tyrone from Long Day’s Journey into Night in the central figure of Mrs Sword. Bald Mountain was rejected by the Adelaide Festival, the third of his plays to be spurned, and it was also a critical disappointment. White’s frustration at having to fight for his work to be staged, and the bitter falling-out with his former darling, director John Tasker, led to his abandoning playwriting, again. Having sold up at Castle Hill, in 1963, White and Manoly Lascaris settled at Centennial Park, where White returned to fiction.

The third phase began a decade later with Jim Sharman’s 1976 revival of A Season at Sarsaparilla. The success of that production and the thrill of working with someone like Sharman, who not only shared his theatrical sensibility – grand illusions, non-representational – but also ‘got things done’, prompted White to write Big Toys in a great rush. Premièred in 1977, this comedy of manners set in a Sydney living room is formally the most conventional of White’s plays.

Set of The Season at Sarsaparilla (courtesy of the University of Adelaide Archive Collection)

Set of The Season at Sarsaparilla (courtesy of the University of Adelaide Archive Collection)

Big Toys was followed in 1978 by Sharman’s landmark revival of A Cheery Soul, with Robyn Nevin as Miss Docker. In 1981 Sharman became artistic director of the Adelaide Festival and commissioned White to write Signal Driver. It has a very personal and somewhat bleak depiction of marriage, dipped in Strindbergian melancholy and sprinkled with music-hall nostalgia via a couple of tramps who are also supernatural Beings standing outside the time scheme of the play’s action. This was followed by the sadly neglected Netherwood, directed by Sharman in 1983 for his Lighthouse company in Adelaide, and hardly seen again. It’s about an asylum for somewhat insane outsiders. Similarly forgotten, and deranged, Shepherd on the Rocks appeared in 1987, a morality play about a charismatic priest who works to convert the sleazier denizen of Kings Cross, directed by Neil Armfield at Belvoir.

If all this sounds like a nightmare to lovers of so-called traditionalist theatre, it is: Patrick White is the nightmare figure of Australian theatre, its dark mirror, all instability, flight, and endless opportunity. Why? Because as a playwright he offers that intriguing combination of profoundly felt obsession and frustration with the stage. ‘One can’t say all one wants to say,’ declared White in 1969, justifying his decision to walk away from the stage five years earlier: ‘one can’t convey it.’ This inadequacy is a recurring theme in the plays: in his young poetasters Roy Child in Sarsaparilla and the Young Man of The Ham Funeral; in Mr Wakeman, the ineffectual parson of A Cheery Soul, who ‘has trouble in finding words’; and, most tragically, in Hugo Sword, the English professor of Bald Mountain (‘We’ll never get through ... never ... never ... however long we live ... however many messages we send ...’).

‘Patrick White is the nightmare figure of Australian theatre, its dark mirror’

White as playwright strives for a theatre of sight and sensation, and struggles to overcome the futility of words. He was ahead of his time to begin with, anticipating though never quite achieving a break with that theatre where the sufficient presentation of words – polished, shimmering, ingenious words – is the first dramaturgical end. Instead, White confronts theatre-makers with the impossibility of complete harmony between text and stage, and the impossibility of a theatre adequate to what the play cost him as a writer. Instead, he offers the dream – or nightmare – as an intervention, a gift of collaboration between the playwright and the director, a gesture which, as we shall see, has been influential in the emergence of an alternative tradition in Australian theatre.

Despite the myth of White wasting his best talents in the theatre, he is a more influential presence there than he is in contemporary fiction. Certainly, there was a time when White represented a kind of Great Wall of China for any new Australian novelist with literary pretensions, but now there is little emulation of his elaborate, highly metaphorical prose style. Even the inner-urban novels of White’s later period, written less ornately, are often thought mannered.

Neil Armfield, interviewed for this article, said: ‘I think that in novel writing today there has been such a swing away from the formal experiments of modernism, White is not as influential, whereas in the theatre, the energy that comes from his work has always been somehow positive.’

It is sometimes claimed that White’s chief influence as a playwright is as an early vector for Continental modernism. This was first expressed in Kippax’s landmark summary of Australian theatre in Meanjin in September 1964: ‘[White] assumes that the Australian plays which he is writing belong to the Western European dramatic tradition and that he can command whatever suits his purpose from its range of styles, techniques and conventions.’

Nonetheless, it is worth remembering that there was already much European theatre – particularly modern French – on Sydney and Melbourne campuses during the 1950s. Wal Cherry’s famous production of The Threepenny Opera predates the première of The Ham Funeral by several years. It is also worth asking what precisely the Western European influences on White’s plays really are? Were they Strindberg, Ibsen, and the German expressionists, as he belatedly admitted in 1989? He had certainly read Wedekind, and he studied German and French, but he imbibed a lot more well-bred English comedy, and there is no doubting his taste for music hall and comedy skits. In trying to untangle the influences feeding into White’s work, and tracing them beyond, we should remember that he talked often about his ‘magpie mind’. Does The Ham Funeral echo the washing of the miner’s body in The Widowing of Mrs Holroyd by D.H. Lawrence, a writer much admired by White? Does the spirituality and ponderous three-act structure of the plays reflect the triptychs of Manoly’s Byzantine icons, as suggested by the critic James Waites? What did White make of the Goons, or the brassy travesties of 1950s Australian radio comedy – or the Phillip Street reviews and Gordon Chater?

Rather than consciously synthesising his artistic influences, White was more interested in solving – or failing to solve – problems of instinct. His view was that ‘our books are poured into us from some other source, and that a supernatural one’. If hedid introduce a modernist sensibility into Australian playwriting, itis secondary to the impact he has had on directors and designers. We don’t feel his presence – not strongly, anyway – in many Australian playwrights. It’s certainly there in Dorothy Hewett, and perhaps in the early plays of Louis Nowra, but few others. In contemporary playwrights like Declan Greene or Lally Katz or Jenny Kemp, you sense a kinship, more because of shared ancestral relations than because of any direct descent.

‘I think with White his influence is much stronger among directors than it is among writers,’ says Daniel Keene, one of the few contemporary playwrights to admit to having read White’s plays. ‘I think it’s almost non-existent among writers.’ For playwrights White is more of a martyred saint: a symbol of perseverance against institutional hostility. ‘It’s hard to take the blows in the theatre business without becoming really paranoid, without worrying about your worthlessness,’ says playwright Patricia Cornelius. ‘Certainly, when you have someone like Patrick being treated so shabbily, you sort of think, well, they’re just arseholes – to everyone.’

‘The history of Australian theatre is almost a history of missed opportunities.’

The history of Australian theatre is almost a history of missed opportunities. Harry Kippax lauded White’s plays as offering Australian drama ‘a leadership which, if other playwrights will attend to what he is demonstrating, may liberate it from the shallows of naturalism and reportage’. That was in 1964. The next decade and a half was a famous time for new writers in Australia – for the Pram Factory and La Mama and Nimrod; for David Williamson and Jack Hibberd and John Romeril. But White was ignored. Australia was not, it seemed, ready for magic, black or otherwise. It was only when White collided with Jim Sharman, and the line of directors and designers who followed, that there were new sparks.

John Tasker is a fascinating character whose seminal contribution to the Australian stage (and to White’s career as a playwright) has been much neglected. His contemporaries – John Sumner, for example, White’s other interpreter from the early 1960s, and Wal Cherry, Melbourne’s champion of Brecht – have found their place in history, as much for their administrative and intellectual accomplishments as for their artistic innovations. Tasker’s name tends to live as something of a footnote in Patrick White’s biography. But it may be time to rehabilitate Tasker and see him as the first in a line of brilliant stage stylists, inaugurating with White a tradition of energetic, creative interrogation between director and playwright.

Tasker was only eighteen when he left Australia for Europe. By the time he returned, in 1959, at the age of twenty-six, he had seen the Berliner Ensemble, heard Jean Cocteau narrate Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex in Vienna, studied modern dance with Sigurd Leeder of Kurt Jooss Ballet, and attended the 1957 Kurfürstendamm Drama Company production of A Dream Play at Sadler’s Wells. He combined a hunger for European culture with what his friends called an ‘expansive Australian enthusiasm’. He was barely off the plane from London when he took on Sartre’s Lucifer and the Lord for the Sydney University Dramatic Society, a severe, almost minimalist production starring a young Kevin Colson. Then came Oedipus Rex at the Cell Block in 1959, performed with robes and gold masks, probably inspired by Tyrone Guthrie’s Stratford, Ontario version of 1957. It was either one or both of these productions that caught Patrick’s speculative eye.

When Tasker premièred The Season at Sarsaparilla at the Adelaide University Theatre Guild in 1962, the partnership with White, less than two years old, was already unravelling. But Sarsaparilla was well received, and Harry Kippax praised Tasker ‘for the ingenuity with which the play’s staging problems have been solved and in tempi which match the restless flurry of incident’.

Tasker, adept at panoramic, horizontal effects, would have relished tackling the formal problem of the three houses side by side. The rapid shifts in mood and tone – from soaring desire to claustrophobic menace, music hall japes to hefty melodrama, the anthill swarm of human life and the twitch and flutter of butterfly courtship – demands sensitivity and flamboyance, for both of which Tasker was renowned. The production was criticised by Kippax for degrading tenderness and dignity and for flattening the wry comedy into a folkish farce. The criticism may have been fair, but we can understand what Tasker was trying to do; he wanted to emphasise the break with naturalism in order to make a harsher Verfremdungseffekt satire of this ‘set of variations on a theme of love’.

In comparison to this hard-edged Adelaide production, the Melbourne Sarsaparilla, directed later that year by John Sumner for the Union Theatre Repertory Company, was a softer, less frenetic and brilliant affair. Poet Chris Wallace-Crabbe described it as a ‘rawhide and stringy bark’ production. ‘Verbally very interesting, incipiently very exciting,’ he recalls, ‘but not the most successful of productions. Rather an attempt to make the theatre do something that the producers weren’t up to.’

Sumner, trying to impose a naturalistic solution on the text, made the most of White’s on-the-money caricatures but shied away from the formal challenges of the text. Thus Zoë Caldwell’s slatternly Nola Boyle (she created the role for Tasker’s production) is remembered for her sexual intensity, while Reg Livermore as the conceited Roy Child, a would-be novelist whose partial narration of the play is one of its great challenges, is hardly remembered at all. ‘I suppose, for some people, the mixture of White’s European modernism and Australian amateurism might have been interesting,’ says Wallace-Crabbe, ‘but it was awkward, all knees and elbows.’

At best, according to the reviewers, Sumner managed ‘admirable competence’. He was a good director, precise and sensitive, but, as Roy declares, ‘Out and in! In and out! Direction is the least of it.’ In a letter to his friend Frederick Glover, White wrote of the Melbourne experience:

The Melbourne production was not nearly so stylish or brilliant as John Tasker’s, but it had some very pleasing touches. Sumner is a sincere producer, with greater depth and mellowness than the Tasker [...] I enjoyed working with him – none of the hysterics of the Tasker; he is not protecting his own uncertainty from any encroachment on the part of the author, which is what I think is wrong with the Tasker.

White may have been right to point up Tasker’s nerviness. According to David Marr, Tasker thought White’s next play, A Cheery Soul, ‘unplayable’ and refused to take it on. The bitter experience of staging the fourth play, Night on Bald Mountain in 1964 irrevocably broke the partnership and poisoned White’s theatrical ambitions.

It is hard to be sure about White’s motives – he fell out with so many people over the years – but Tasker’s way of camouflaging his doubts and disquiet would not have encouraged the tit-for-tat of ideal collaboration. As Daniel Keene says, apropos of White and the interest he has for directors: ‘As a playwright, what I expect from a director is push back. I push the play across the table and I want questions coming back at me.’

Tasker may have launched this tradition of progressive, visually adventurous directors’ theatre, but he didn’t follow through. In Marr’s words, he was ‘always making a comeback’. He returned to Australia, like White, and like Jim Sharman nearly twenty years later, with the hope of leading a cultural golden age, and he did briefly show a flair for innovation, launching the South Australian Theatre Company with a production of Andorra, the Swiss playwright Max Frisch’s epic-theatre parable on the mechanics of bigotry, again starring Livermore. Although he seemed to lose his pioneering faith, his early work in Sydney and his collaboration with White remain influential. As a teenager, Jim Sharman saw Tasker’s productions of The Ham Funeral at the Palace and Sarsaparilla at the Theatre Royal. ‘The original productions of those plays,’ he recalls, ‘which Patrick was always very critical of, were actually very good, for their time. I felt they had a kind of mythic aspiration in them.’

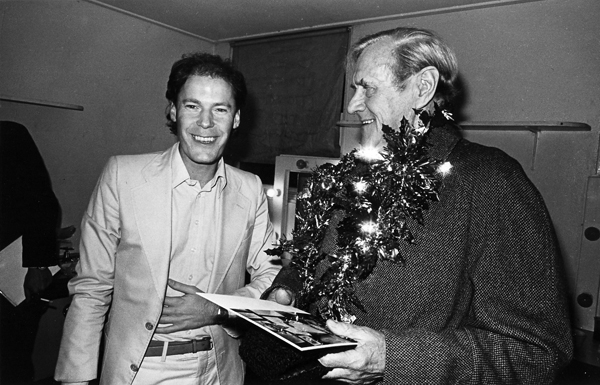

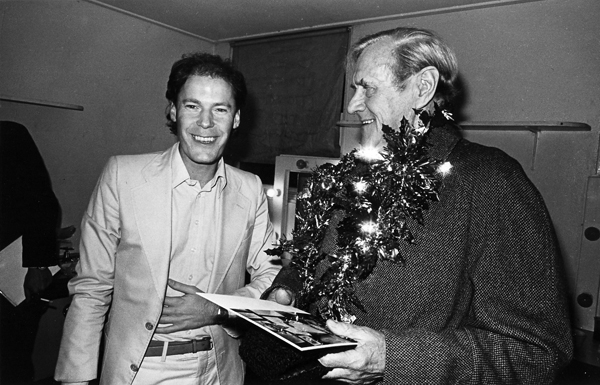

Jim Sharman and Patrick White backstage after the opening-night performance of Big Toys, Parade Theatre, Sydney, 1977 (photograph by William Yang)

Jim Sharman and Patrick White backstage after the opening-night performance of Big Toys, Parade Theatre, Sydney, 1977 (photograph by William Yang)It is 1975. Jim Sharman, aged thirty, has just agreed to direct a new production at the Old Tote Theatre in Sydney. From London to New York, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, which he co-wrote and directed, has embarked on what will become the world’s longest theatrical run. His production of Jesus Christ Superstar is still running in London and will do so for another five years. The phone won’t stop ringing: everyone wants him to direct Andrew Lloyd Webber’s new musical. He is not sure what he wants to do, but after almost a decade travelling the world and directing what he thinks of as upmarket sideshows, he knows it will be back in Australia – not in London, and not with Evita.

Sharman suggests a revival of Season at Sarsaparilla for the Old Tote in 1976. As he sees it, White offers him a chance to reconnect with Australia, as well as a new way of viewing the world. He hasn’t forgotten those early Tasker productions, that voice both familiar and imaginatively strange. ‘In Season at Sarsaparilla I heard a voice I recognised,’ he recalls, ‘and it stayed with me.’

Jim wasn’t simply born into showbiz royalty; he was also born into a family of extraordinary mythmakers. There are many stories about his grandfather and father and their famous travelling boxing show, but, as Peter Corris notes in his history of prize fighting in Australia, Lords of the Ring (1980), it can be hard to sort the truth from the legend. Sharmans, it seems, have an instinct for legend.

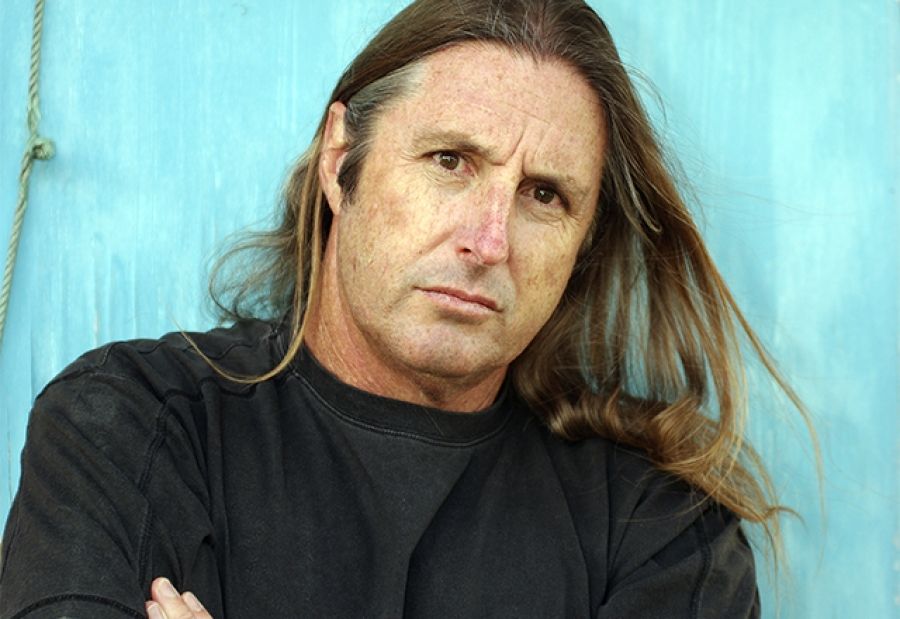

He remains an impressive personality – very sincere, very interested. Full of youthful energy, he is still a showman, though, as Kenneth Tynan said of Peter Brook, he radiates nothing more alarming than confidence. It’s a perfect Sydney day when we lunch on the roof of the Museum of Contemporary Art. As we discuss epic theatre and ancient rituals, we watch the boats on the harbour.

Sharman calls Patrick White the mentor he was always seeking. White made him believe that Australia was a place where he could put down roots. It was White after all who wrote to Manfred Mackenzie in 1964: ‘I was just fascinated by the idea of returning to one’s origins after exploring the “world” and finding in those origins the perfection for which one had been looking.’ Origins were what Sharman saw in Sarsaparilla, and what he wanted to explore: ‘Until Sarsaparilla, most Australian theatre had implied that life was something that happened elsewhere – usually London, Paris or New York.’ White’s play changed all that.

‘We understood that what we were seeing was something very ancient,’ he says. ‘We’re not just seeing something that happens in an Australian suburb, we’re actually seeing something that goes back centuries. And that’s what you have to stage, the hidden play.’

Sharman insists that his understanding of Australian theatre – and what Australian theatre is capable of – comes from a more ancient tradition than The Recruiting Officer.

‘Corroboree,’ he says, gesturing vaguely toward Kirribilli with an unlit cigarette. ‘That’s where Australian theatre comes from. And corroboree involves a sense of deep ritual.’ For Sharman, White was engaging with Australian suburbia as part of an ancient story. The solution to the problem of the three houses and the overlapping lives was the medieval morality play, where three carts were wheeled into a market square: heaven, hell, earth. Obviously, this is always likely to attract a dramatist who lusts for interpretation if the interpreter is a director who will embody the work powerfully. ‘Wendy Dickson’s design spread the three kitchens of heaven, earth and hell across the letterbox stage of the Sydney Opera House like three vivisection slabs,’ says Sharman. ‘The production was stark, bright and Brechtian.’

But it is Sharman’s 1977 production of A Cheery Soul, in terms of the state of contemporary Australian theatre, that was especially influential. It is one of those rare moments when an opportunity to do something profoundly different in Australian theatre, on a large scale, was actually seized.

‘A Cheery Soul is the one that I am mostly connected with, having mostly taken it from obscurity and loathing to what I now believe is a classic,’ says Sharman.

Brian Thomson, who had been coaxed into designing for the theatre by Sharman and had worked with him on a production of As You Like It many years before, was again enlisted. Thomson’s lateral, pop art-inspired designs helped Sharman to sweep away the last remnants of deference that had informed his Sarsaparilla revival.

‘Jim pretty much wanted the full shebang,’ recalls Thomson. ‘He wanted a revolve from the kitchen to the full mansion, I just said, “Jim, I think that’s wrong. It’s exactly what’s happened from the short story to the play: so much junk has been added to it. I think we should strip it back and try to get to the simplicity and strength of it.”’

They opened with the victims of Sarsaparilla lit like spirits on an empty stage, the ‘manic clockwork mouse’, Robyn Nevin’s Miss Docker, staring out with an ominous pantomime grin. As the scene moved into the kitchen at the Custances, a Brechtianhalf-curtain, low, billowing silk, swept across the stage as a background. Thomson cites the art of Christo as his major influence here, particularly his ‘Valley Curtain’ of 1972, a colossal fiery orange curtain drawn across Rifle Gap in Colorado. It was this minimalist, almost oriental aesthetic of veils and grandeur, combined with Jim’s interest in the cool expressionism of the Berliner Ensemble, that helped them to find a way through White’s elaborate, problematic stage directions.

When, with Sharman’s Cheery Soul, White at last found the kind of theatre he wanted, he was already old. His resources were finite, he was not going to master a new idiom of dramatic art, and, as a playwright, he could not, despite his evergreen iconoclasm, always articulate the revolution he felt was necessary. But he believed that Jim Sharman and Brian Thomson could. Perhaps there was an obscure prophetic sense that one day a Benedict Andrews and a Robert Cousins would. What White offered them was collaboration: a kind of destiny. Great novelist though he was, he knew that his theatrical interpreters, particularly the director, had to bring him to fulfilment. To an unusual degree, the old man knew that future shamans and tricksters would be the co-authors of his work for the stage.

This ‘White line’ of collaboration from Tasker to Sharman to Armfield to Andrews is a chain of elaborate interdependence between White and his directors, his directors and his designers. There is a deep sense (passing the usual symbiosis between director and playwright) in which they articulate dramatically what he cannot put into words.

If there is mythmaking involved in this argument, it’s the kind of legend that is necessary for a mature theatre culture. Our history should teem with such myths, because they provide a necessary archaeology and genealogy. They are in some sense the poetry of the business, its meaning, more able to elevate and inspire than uncollected gossip and partial histories. Jim Sharman cottoned on to the power of this particular myth from the start. It was Sharman who declared that in order to succeed as a director in Australia you had to first tackle Patrick White.

‘I was conscious of that from the moment I met Jim,’ says Benedict Andrews. ‘I wasn’t really aware of that tradition before I assisted him on Miss Julie, but he very much impressed it upon me. Jim loves these sort of myths.’

Even Sharman’s autobiography, Blood and Tinsel (2008)is dedicated to ‘those who come after’. Principally, he encourages his successors to wrestle with the plays written by the author of Voss. If that is the great latency of Australian theatre, if White’s plays are sketches towards a possible theatre, they have to complete the picture by enacting them.

One of White’s finest monologues comes from perhaps the least familiar of his plays, Shepherd on the Rocks, a morality play on a comic subject, full of technical problems and thematic paradoxes, which Neil Armfield describes as ‘Patrick’s Tempest’. It begins:

Are you for magic? I am. Inadmissible when we are taught to believe in science or nothing. Nothing is better. Science may explode in our faces. So I am for magic. For dream. For love.

This is what White wanted from his theatre, magic and dreams and, where the magic was potent enough, love, the kind of world-consuming love that exceeds the scope of the stage and justifies the theatre as a place of worship and enlightenment: a place to nurture faith and the inner life, and a place to renew our vision of the world.

So how is a Prospero set free in the theatre? How does the magician learn her craft? As the American poet John Hollander once said, magicians, like prophets and poets, learn their craft from their predecessors. Just as Sharman was informed by Tasker’s productions in the 1960s, Neil Armfield bore the indelible mark, the enduring memory (and concomitant know-how) of Sharman’s productions.

‘Those three White productions of Big Toys, Cheery Soul and Season at Sarsaparilla, and particularly his work with Brian Thomson,’ recalls Armfield, ‘it was just so clean and muscular and theatrical and stripped back of all of the prettified shit that more picture box and representational theatre was concerning itself with.’

‘As a man of the theatre, the greatest of Australia’s literary artists, the supreme auteur saw himself as one member of a team.’

Although Armfield got his start at Nimrod and had numerous mentors, collaborators, and inspirations, he was in a deep sense invented at Sharman’s Lighthouse theatre in the early 1980s. With Benedict Andrews, too, there are many influences and inspirations beyond anything that can be directly traced to White. But the importance of his apprenticeship with Sharman and Armfield early in his career cannot be underestimated.

‘I can’t think of anything worse than if a young director simply wants to be the generation before. You have to want to destroy them,’ says Andrews. ‘But I also felt a deep sense of belonging in their rehearsal rooms, because they were serious theatre artists.’

One of the ways in which White’s work exerts a deep influence and breaks with orthodoxy is in its rejection of the aesthetic mastery of the sovereign artist. White’s texts cry out for intervention; they need all the skills of their interpreters if they are to work. It is telling that after his experience on Sarsaparilla, White asked a bemused Brian Thomson to write all the stage directions for Big Toys. According to Thomson, ‘that’s what was published’. As a man of the theatre, the greatest of Australia’s literary artists, the supreme auteur saw himself as one member of a team.

Paradoxically, toward the end of his life, there was, in the words of Barry Oakley, an ‘atmosphere that increasingly resembled a prayer meeting’ around the text of Patrick White, a level of textual respect that may have got in the way of doing justice to the plays. But even then, Armfield was still wrestling with White’s text. He may even have inserted new lines into his production of The Ham Funeral, and rewritten the supposed master, setting the scene for his later drastic revisions of A Cheery Soul and Night on Bald Mountain in the 1990s.

The passage that crowns David Marr’s brilliant biography of Patrick White (1991) is his description of Neil Armfield’s 1989 production of The Ham Funeral:

There was applause as he came down the stairs into the foyer. The cast trickled in to join the audience. White had been planning his gift to the cast for months: a cake with Dobell’s dead landlord in icing sugar. The two Alma Lustys would cut it together. Joan Bruce and Kerry Walker each took a hand on the knife. Armfield spoke. White autographed programmes, talked, sipped a glass of white win, and said again, ‘This is the most exciting night of my life.’ Lascaris was beaming and his face was wet with tears.

This is Marr at his best, drawing us effortlessly us into the warm, familial glow of White’s final triumph. Almost half a century before, when a West End production of Return to Abyssinia was cancelled, White wrote to his then lover, Pepe Mamblas, ‘I shall never get over the disappointment of this.’ Here, though, we sense a lifetime of disappointment and frustration melting away as the old man finds peace at last.

It is a scene worthy of Armfield himself, the dramatic master among directors of humane feeling. ‘That was the first revival of Ham Funeral since its first production in the sixties,’ remembers Armfield. ‘Patrick was around from the beginning of rehearsals, and that was great. I did it for Patrick really. He was very anxious about the play. But it worked.’

It worked not only as a parting gift to White, who died less than a year later, as a crowning celebration of his contribution to Australian theatre, but as a way of reconciling White’s vision with the sensibilities of mainstream Australian theatre. No production before or since has done more to establish The Ham Funeral as a classic or to confirm White’s place in the canon, his centrality to the repertoire.

Although Sharman’s 1979 Cheery Soul was a breakthrough moment, shattering orthodox notions of how an Australian play on the big stage should look and sound, he was sometimes accused of a perceptible lack of human feeling in his productions. Katharine Brisbane remembers telling him at the time, ‘I’ll give you a good review when you begin to put human beings on the stage.’ It was Armfield, more than anyone, who would put the human being back into White’s plays and ensure that no thinking audience could doubt the compassion of this old black-hearted denouncer of the horrors of Australian life. What is remarkable is that he did it with The Ham Funeral, which is perhaps the most cracked and anti-humanistic of White’s plays – the bestial one, the ‘play about eels’ – where characters flicker between realms that seem either ethereally symbolic or sordidly real. Armfield contrives to make the awkwardness and clumsiness of the script its virtue, portraying the Young Man of the boarding house as the author of his own existence, and therefore making his obstructed realisation (which has its origin in White’s radically imperfect craft) part of the drama: the poet’s struggle with self-expression, his actuality wavering mesmerisingly with the imperfections of his talent.

Through pure directorial wizardliness, this gives the work an affinity with some of the great modernist works about the limits of human expressiveness: with Joyce’s Ulysses, or Beckett. And Thomson tuned the audience into all this meta-theatrical possibility by wrapping the words with which White sets his play around the high walls of the Wharf Theatre (‘A great, damp, crumbling house, anywhere’).

The story – once described by White as ‘an act of indecent exposure’ which ‘should be discreetly forgotten’ – becomes that of a damaged young man finding wholeness in the breathing world through the recognition of love and affection in another, however crippled the confines of White’s original dramatic conception:

This pattern of theatrical repair characterises much of Armfield’s work. He is fascinated by the process through which a broken human scenario is reconciled, that final, warm light as the young man strides into the soft night where (‘I could put out my hand and touch it ... like a face’).

Armfield’s highly developed sense of human frailty, even his tendency towards sentimentality, lead him to achieve an unexpected tenderness beneath the young artist of Ebury Street’s odious self-awareness. He clarifies into drama the frustrated craving for recognition that infects the play at an almost elemental level, and makes it look unaided, like an extravagant bit of juvenilia.

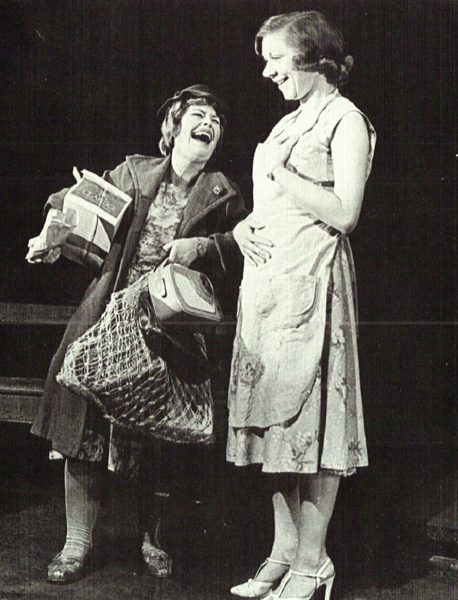

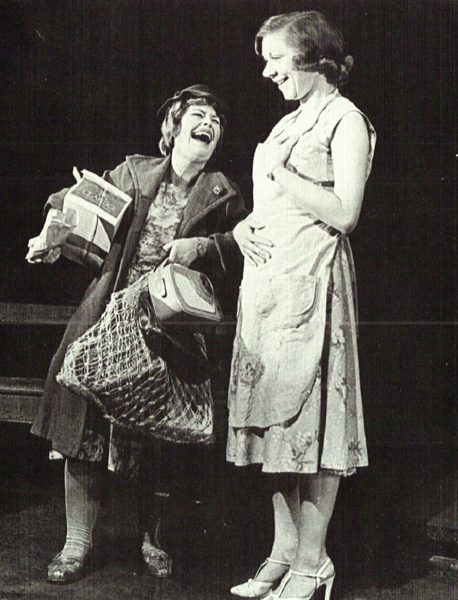

Robyn Nevin and Pat Bishop in Sydney Theatre Company and Paris Theatre Company’s 1979 production of A Cheery Soul (photograph by Branco Gaica, courtesy Branco Gaica and the STC)

Robyn Nevin and Pat Bishop in Sydney Theatre Company and Paris Theatre Company’s 1979 production of A Cheery Soul (photograph by Branco Gaica, courtesy Branco Gaica and the STC)

In Armfield’s 1996 production of A Cheery Soul, with Robyn Nevin reprising her role as Miss Docker, there was a similar emotional discovery, that of a gentle spirit at the heart of a character described by Nita Pannell – the first Miss Docker – as ‘completely unloved’. The audience that laughed at Nevin in 1996 did so more in affectionate recognition; it was not the horrified laughter which greeted the Genet-like monstrous female of Sharman’s 1979 production.

‘Having only really read Patrick White at university and having thought of him as an unemotional, harsh, literary personality,’ says director Michael Kantor, who was in the audience for Armfield’s 1996 MTC production, ‘suddenly his play became deeply humane.’

It is this ability to penetrate the heart of feeling in White’s often unlikeable-seeming characters and to make them connect with potentially hostile audiences that has made classics of White’s plays, and that has also led to the recovery of works like Night on Bald Mountain, reprised in 1996.

In September 1962, writing to Wendy Dickson, a designer for the Elizabethan Theatre Trust, Patrick White said, ‘I feel more than ever I must have my own theatre, and bring everybody together to do the things we ought to be doing.’

Those were the days of Patrick’s greatest enthusiasm for the stage. Season at Sarsaparilla had just opened to packed houses in Adelaide. He had already written A Cheery Soul, which he knew to be his best yet. Two months earlier, Kippax had declared the Sydney production of The Ham Funeral ‘an epoch making event’.

Though a bitter critic of Australia’s ‘reactionary Establishment’, with an assiduously cultivated reputation as an antisocial outsider, White never thought of institutions – especially in the arts – as inherently detestable. He regarded new theatrical endeavours with interest. When the Old Tote opened in Sydney with The Cherry Orchard, White claimed for the new venture an ‘aura of success’. Even after the personal disaster of Night on Bald Mountain in 1964 he continued to support Sydney theatre.

White could never have run his own theatre. He was no Brecht, but it is remarkable to see how often White was present at the birth of new theatrical ventures. In 1978, with the Old Tote floundering, White’s dream of his own theatre was revived by Sharman and Rex Cramphorn. When the Sydney Theatre Company was launched in 1979, it opened with Sharman’s innovative production of A Cheery Soul. When Sharman relaunched the State Theatre Company of South Australia as Lighthouse, it was with Armfield’s première of Signal Driver. When Nimrod’s old venue in Surry Hills was purchased by a syndicate of over 600 investors, White became the company’s biggest individual shareholder.

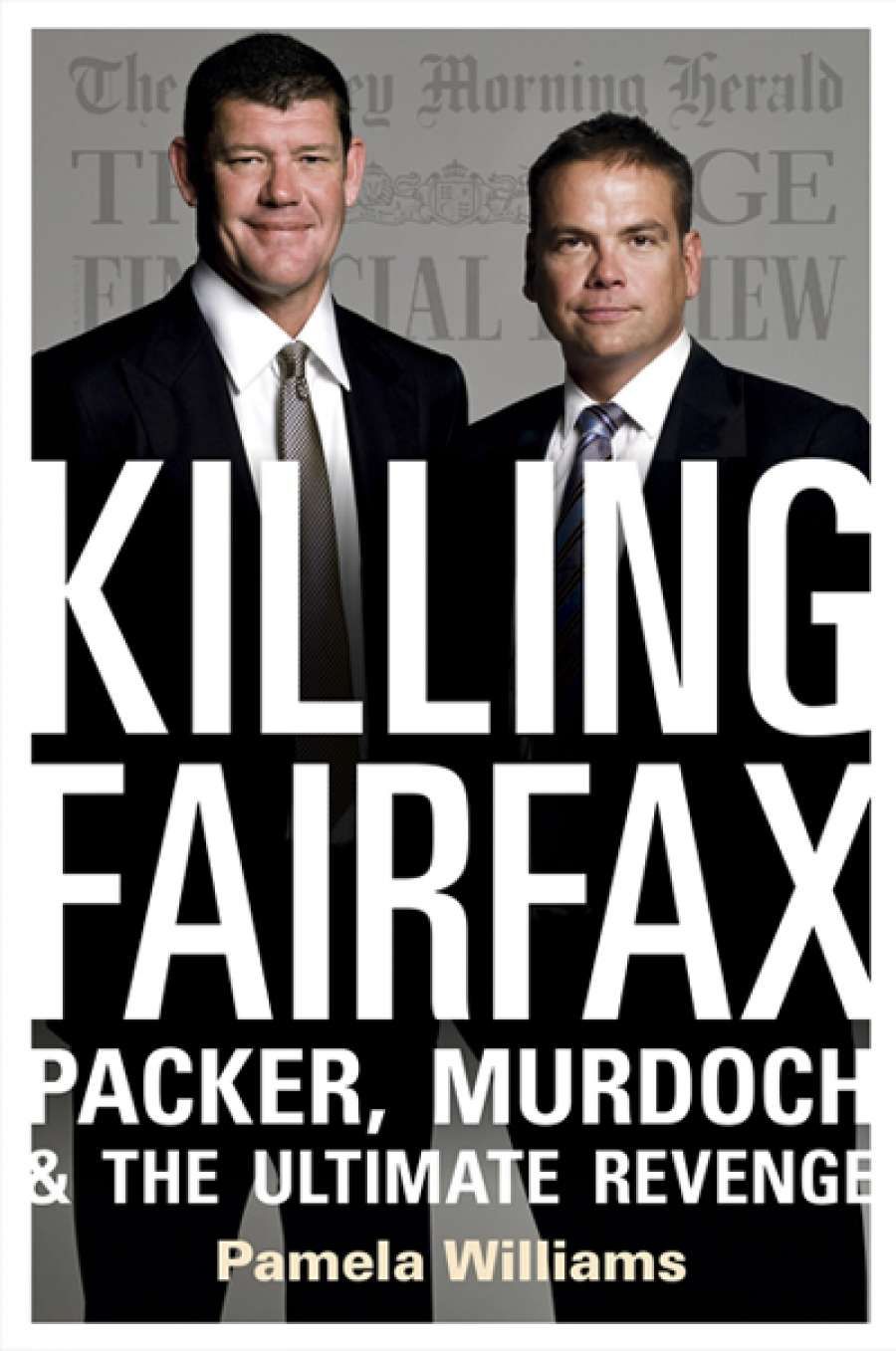

John Gaden and Kerry Walker in Signal Driver (photograph by Régis Lansac, courtesy of Belvoir)

John Gaden and Kerry Walker in Signal Driver (photograph by Régis Lansac, courtesy of Belvoir)

‘In 1985 we bought Belvoir,’ remembers Armfield, ‘and Patrick was involved in the purchase and bought eight shares. We were looking for something to be the first production and it seemed completely right that it should be Signal Driver.’

Belvoir is one of the great triumphs of that spirit of creative adventure championed by White. It has influenced Australian theatre as much, if not more, than any other company in the country. If, more than twenty years after his death, Patrick White remains a potent influence, a symbol of where a progressivist Australian theatre comes from and where it can go, his Belvoir is our nearest institutional expression of this.

When Michael Kantor became artistic director of Playbox in 2004, the board asked him to ‘refresh’ the brand. Young audiences had lost interest in the text-heavy naturalistic Australian dramas. So Kantor relaunched the company as ‘Malthouse Theatre’, dropping the word ‘play’, shifting the dramaturgical focus away from the script and the author, and promoting a more collaborative process between director, designers, and performers. The Malthouse opened with Kantor’s production of The Ham Funeral. It was Kantor’s second production of the play (his first was at Belvoir, in 2000). Kantor intended his production, in which the vaudeville was given a nightmare twist, as a critique of the state of Australian theatre: ‘I wanted to make a statement about what it [The Malthouse] was not going to be,’ he told me. ‘It was not going to be a whole lot of naturalistic plays.’

Exuberant, adventurous, and full of spectacular imagery, Kantor’s Malthouse became a beacon – sometimes flickering and uncertain – for a new generation of theatre-makers in Melbourne. Although he says he wasn’t aware at the time that Belvoir had also launched with Patrick White, he appreciates the coincidence. Kantor was championing White as an alternative to Australian realism and essentialism. ‘I think his theatre is about dreams and nightmares,’ he says. ‘I don’t think he thought of the stage as a place for realism.’

It speaks to something, to a kind of seminal, mythical potency, that White’s plays are always there at the start of new and sometimes radical shifts in Australian theatre culture. Whether we attribute this to inspiration or to the inevitable attraction of the newly ambitious, there is no doubting the glow of anticipation he arouses or the way his work functions as a banner under which new things are done.

For a susceptible young hopeful, looking for something – anything – that challenged received ways of seeing the world through dramatic art, Benedict Andrews’ production of The Season at Sarsaparilla was a revelation. All at once Australian theatre made sense. All at once it looked like a medium for serious artistic expression, for desires and the frustration of desires, a thing of involuted compositional complexity and intimate connections, not stick-figure pseudo-seriousness and jolly farce.

I saw it three weeks into the Melbourne season, and was transfixed by the scenic virtuosity, the brick veneer house hanging in wastes of darkness, the foundational cell of the Australian sprawl; the theatricality of the slowly falling tinsel, the razzle-dazzle filling for a moment the emptiness of the stage, the Hammond organ, stage left, rising like the morning sun; by the intimations of quiet desperation beneath those warm suburban portraits, the sense of alienation, the existential anxiety; and by the sharpness of the critique, White’s booming frustration at the materialist claustrophobia of the suburbs transformed into a premonitory warning against the absolute transparency and horrifying banality of what Paul Virilio calls the ‘pure war’ of twenty-first-century surveillance, where every basic experience – especially love – is filtered through the transmission of images. That was in 2008. The production had premièred the year before at the Sydney Theatre Company. Was this, I asked myself, the kind of theatre they do in Sydney?

‘Maybe there is something very populist and sexy in Sydney,’ muses Andrews. ‘I hate to use this word “sexy”, but when I think of how beautiful that city is, and the heat that’s in it, and where these two theatres sit on the shore there, well, there really is a lot of energy.’

Is Sydney the city of creators, Melbourne of operators? Which group does a theatre director belong to? Christina Stead said she could create in Sydney because it has ‘a rocky basis’, whereas Melbourne, like London, is built on mud. White knew Sydney as the source of his love and hatred, hence of his creative energy. It was also the place that had given him the two golden boy directors of his old age. Melbourne for White was the ‘city of sodden rectitude’.

It was 1997, and Barrie Kosky, that Melbourne agitator, had just driven a leopard-print stretch hummer called Tartuffe through the Sydney Theatre Company, crushing with it a program weighed down with Williamsons and Raysons. Tartuffe, with Jacek Koman and David Wenham, was artistically and financially successful. His next two productions at the STC, O’Neill’s Mourning Becomes Electra and Oedipus, didn’t pack houses, but they galvanised and inspired a generation of artists.

Andrews was brought in by Robyn Nevin, not only an actor of the old dispensation and one of White’s favourites, but also a capable naturalistic director. As artistic director of the STC, Nevin worked with both Stephen Armstrong (who later ran the Malthouse with Kantor) and later Tom Wright, as artistic associates. Both were committed Koskyites; between them they helped forge an alternative Sydney Theatre Company within the STC, as part of which Nevin brought in the dynamic Benedict Andrews as resident director from 2001 to 2003.

‘When Benedict came and did Faustus or those early Martin Crimps,’ remembers Tom Wright, ‘he was met with the kind of stupefied incomprehension that Sarah Kane was met with in the UK. He was banging his head against the door there for a long time, and in the end the only thing that opened it for him was the wonderfully inexplicable success of Season at Sarsaparilla.’

Andrews first encountered Patrick White in 1994, when Jules Hollege, an academic at Flinders University, suggested that he consider directing White’s Netherwood as his graduation piece. ‘I remember feeling immediately electrified by it,’ he recalls. He began working through the rest of the novels and plays. ‘At that time I was looking, particularly through the festivals, for a theatrical literature that went beyond the well-made play,’ he says. ‘And in a way I still am. I’ve always looked for plays with a difficulty or problem or radical proposition in them.’

He immediately saw in White a unique, never less than problematic vision of the world. Here was one of the few writers who had found the mythic large-scale grand narrative of the white Australian experience, but who had also torn the veil from suburbia and seen the mythic behind that.

‘I was thinking about this very, very particular voice and I think I was already very much falling in love with this feeling of familiarity, this world of my parents,’ says Andrews, ‘but also feeling the landscape that I knew so well suddenly taking on a mythic quality.’

For Andrews, each of White’s plays consciously or unconsciously sets up something like a formal proposition that is the dramaturgical motor of the play. He invents something that hasn’t been invented before – a new problem that demands its own technical solution. The difficulty in Sarsaparilla is that of the three houses side by side. Andrews’ solution – his very personal one – was to fling the play into the hypothetical space of the Schaubühne Theatre, the Berlin theatre where Andrews once trained and a place that stands as symbol of the internationalist avant-garde theatre about which Australia, including intellectual Australia, is highly ambivalent.

Soon the torch will be passed on again. Malthouse Theatre associate artist Matthew Lutton is to direct White’s Night on Bald Mountain for the company’s 2014 season, resurrecting a play which has – almost unbelievably – been seen only once before in Melbourne, and that in a small university production.

It will feature Julie Forsyth, that notable gargoyle–clown of the Australian stage, as Miss Quodling, the goatherd whose cosmic goat-wisdom bookends the play (‘Their yeller eyes know as much as they’re allowed ter know. Only I know everything ...’). Forsyth, who played Mrs Lusty in both of Kantor’s versions of The Ham Funeral, as well as Mrs Watmuff in Armfield’s 1996 A Cheery Soul, has a kind of rough-as-guts zaniness that is perfectly at home in White’s Sarsaparilla. Surely the time is ripe for her to play Miss Docker? It’s been more than a decade since we last saw that creature of monstrous optimism thrusting her pins of goodness into the feeble hearts of Sarsaparilla. We need to see her grotesqueness reincarnated again.

Night on Bald Mountain was first revived by Neil Armfield in 1996, despite White’s advice that it was ‘a dishonest play’ and not worth reviving. His production inspired David Marr to suggest that perhaps White should never have turned his back on the stage in 1964. ‘This is a verdict I never thought I would deliver,’ he declared. Who knows what his verdict would have been if in 1966 he’d written another Bald Mountain and The Solid Mandala had remained an unfinished draft in a library vault. Would that have been another ‘O fuck’ moment’?

Although Bald Mountain is Lutton’s first White production, he does have a strong connection with two recent interpreters, having worked with Armfield on Toy Symphony (Belvoir) and Kantor on Tartuffe (Malthouse). The prospect of a Lutton Bald Mountain is something to look forward to, but White offers a standing invitation to any director or designer who wants to show what can be done in the theatre. It would be marvellous to see that new darling of the STC, Kip Williams, find something unexpected and fresh in Big Toys, or Anne-Louise Sarks, director in residence at Belvoir, with her scalpel-like ability to reduce a play to its essence, mount a new radically stripped-back Signal Driver. How about letting Daniel Schlusser work his seething deconstructive realism on the manic cavalcade of Shepherd on the Rocks or the dream-like slaughter and chaos of Netherwood? No one would be better than the man who did Bernhard’s The Histrionic with Bille Brown to test Elizabeth Schaffer’s claim that meta-theatricality is the key to White’s dramaturgy or to exploit the violence lurking beneath these two final plays. White’s last four plays have not been seen for more than twenty years. Is it that they are simply no good? The first four plays seem ahead of their time; the second four a little too much of it, bound up in his exacerbated activism, or too wise, even complacent about the kind of theatre he was writing for, and not ambitious enough. Then again, are they ‘dotages’ akin to Memoirs of Many in One? (1986).

But we should be careful of the late work of geniuses. Now is surely the time to prove that. With the recent flood of radical adaptations of the classics, why aren’t we seeking a radical reinterpretation of the Australian repertoire? Why not extend the work of Armfield and Andrews and begin tearing into these late plays? Perhaps a feminist interpretation, something to test White’s misogyny, creatively, in the way that modern interpreters of Strindberg have been doing for decades. It was heartening to hear of Adam Cook’s punk-Gothic take on The Ham Funeral at last year’s Adelaide Festival, but why not push that Gothicism to its most spectacular extreme, as White may himself have imagined when he suggested that The Ham Funeral could now only work as an opera?

We don’t yet know what Patrick White can do. It’s time the dramaturgical potential of all his plays, not just the first four, was fully explored. As Neil Armfield says:

White’s theatre is a kind of time bomb and it has these explosions – usually connected with a particular director, or a particular director and designer – that really change the shape of what Australian theatre is like, and I think Australian theatre is its own thing because of that.

Plays should be challenging. They present opportunities that the theatre rubs up against in order to create new forms, like the ideal grain of sand in an oyster. They retain influence: problems return, and should return, and the solutions creates new problems. Who can now approach Patrick White without confronting Benedict Andrews’ hidden-camera Sarsaparilla? This is how an artistic culture develops and continues to speak meaningfully, through lines of recognition and inspiration from the past, as it gropes uncertainly towards the future.

My thanks to those who generously offered me their time and expertise. In particular I would like to acknowledge my interviewees: Benedict Andrews, Neil Armfield, Adam Cook, Robert Cousins, Peter Craven, Alison Croggon, Peter Cummins, Ian Donaldson, Michael Kantor, Daniel Keene, David Malouf, John McCallum, Jim Sharman, Sam Strong, Brian Thomson, Denise Varney, James Waites, Tom Wright, and Chris Wallace-Crabbe.

ABR Fellowships, funded by private patrons and philanthropic foundations, are intended to generate fine, incisive writing and to broaden the magazine’s content. This is the third ABR Ian Potter Foundation Fellowship we have offered. Each Fellowship is worth $5000. Click here for details.