- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

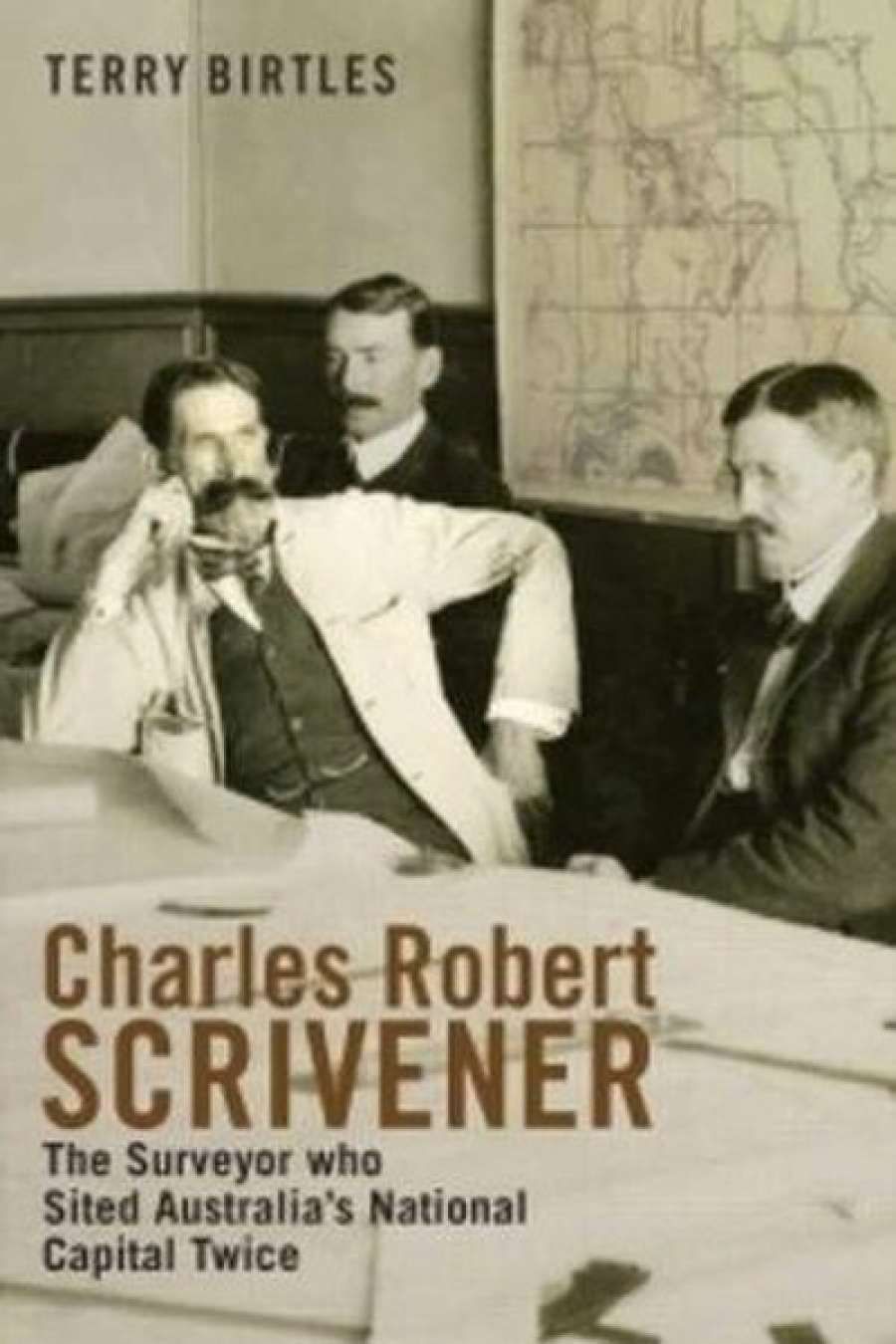

- Custom Article Title: Richard Broinowski reviews 'Charles Robert Scrivener'

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Compromise

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the 1890s the six Australian colonies were preoccupied not only with getting a fair deal over tariffs and customs – and maintaining the purity of the Anglo-Saxon race – but also with the location of the national capital. Denizens of Melbourne and Sydney felt that it should be one of them. The compromise was a capital in New South Wales, closer to Sydney than Melbourne, but with Melbourne as the seat of federal government until it was constructed.

- Book 1 Title: Charles Robert Scrivener

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Surveyor who Sited Australia's National Capital Twice

- Book 1 Biblio: Arcadia, $39.95 pb, 304 pp, 9781921875588

Ingrained with the European tradition of escaping the heat of summer, Sydney and Melbourne gentry wanted an alpine capital. In a tongue-in-cheek editorial, the Sydney Morning Herald stipulated that the site must be bearable in the dog days, have first-class sanitation and ample building material (marble), be close to a branch railway, possess a butcher, pasteurised milk vendor, and a Syrian peddler, and be close to a good racecourse, but as far as possible from deserted mining townships.

In 1904 a New South Wales surveyor, Charles Robert (Charley) Scrivener, was commissioned by the new federal department of home affairs to find a likely site. In this meticulously researched, richly illustrated, and entertaining book, Terry Birtles explains why Scrivener got the job. Born to immigrant parents in 1855 at Bexley Farm on the rural fringe of Sydney, Scrivener was a knockabout product of his time. He was physically strong, good with horses, could sail a boat, and had been hardened through manual labour in his father’s expanding merchant businesses. Surviving an Anglican school environment, where corporal punishment was commonplace, Scrivener excelled at mathematics and, on his twenty-first birthday, became a cadet geodetic computer in the New South Wales surveyor-general’s office.

Before being chosen to survey sites for the national capital, Scrivener surveyed many parts of country New South Wales and metropolitan Sydney. With his young wife, Lena, he was first sent to Hay. He was later transferred to Bathurst and thence to Sydney, where he surveyed market gardens, timberyards, workers’ cottages, and meatworks. In the next ten years he surveyed much of western Sydney, the south coast, and parts of the Blue Mountains, always with his physical toughness, prodigious energy, bushcraft, and mathematical skills to see him through.

Scrivener also needed mental toughness to survive the untimely deaths of Lena from typhoid fever in 1883, and his second wife Mary Beatrice from puerperal fever after giving birth to a son, Robert Massey, in 1886. His third wife, Annie Margaret, whom he married in 1889, survived to raise his children by the first two marriages as well as her own; she outlived Scrivener by twenty-three years.

An early favourite for the national capital was Dalgety on the Snowy River. It matched Scrivener’s insistence on adequate water for hydropower and a growing population, but the harsh site was rejected by parliament in 1909 in favour of a natural north-east facing pastoral amphitheatre near Lake George. This was centred on a sheep property, ‘Canberra’, where the Murrumbidgee, Cotter, and Molonglo Rivers converged.

In 1909, Scrivener became director of Commonwealth Lands and Survey, and went to Melbourne to receive instructions on surveying the new capital site. In April 1910, King O’Malley, an American converted to ‘Christian Socialism’, became minister of home affairs and thus Scrivener’s boss. Scrivener wanted to deal with essentials first, such as surveying a water supply and power station, but had to consider surveying an observatory (at Mt Stromlo), a university, rifle ranges, military barracks, and remount depots. He was also distracted by numerous visitors, including promoters of British military interests such as Field Marshall Viscount Kitchener and Admiral Sir Reginald Henderson RN, who were appraising the capacity of the new Federation to provide troops under British command for the great war they suspected would soon erupt in Europe.

Without consulting Scrivener, the federal government held an international competition for the design of Canberra. The winner, Walter Burley Griffin, an American from the Chicago Prairie School, was wedded to lakes and grand designs; in his Canberra plans he linked geometry and landscape, the city bestriding five ornamental lakes. The thirty-seven-year-old Griffin was invited to Melbourne to justify his plans on 17 July 1913 (his first trip to Australia), and was appointed Federal Capital Director of Design and Construction, and thus senior to Scrivener. It is clear from the beginning of their association that Griffin and Scrivener agreed on little, their initial mild enmity exacerbated by wounding (and untrue) accusations from Griffin that much of Scrivener’s survey work was inaccurate and sloppy. Birtles notes that supporters of Griffin tended to dismiss Scrivener and his Home Affairs colleagues as conservative, doctrinaire, or visionless. But Scrivener’s vision of a federal capital city took account of practical urban requirements such as water supply, physical setting, drainage, transport, and waste disposal.

Scrivener retired and died in 1923, three years before the new parliament house was opened by the duke of York on 9 May 1927. Birtles’s book encourages me to fantasise, as I did about my grandfather in A Witness to History: The Life and Times of Robert Broinowski (2001), how thrilled this taciturn but kindly surveyor would have been to see a city realised in which he had invested so much physical and mental effort; to take part, especially, in the inauguration of the Scrivener Dam; and to see Lake Burley Griffin gradually fill, lapping but never spilling over the stone banks Scrivener had so carefully surveyed around its broad perimeter.

Comments powered by CComment