- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Custom Article Title: Frank Bongiorno reviews 'Dancing with Empty Pockets'

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Push and shove

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

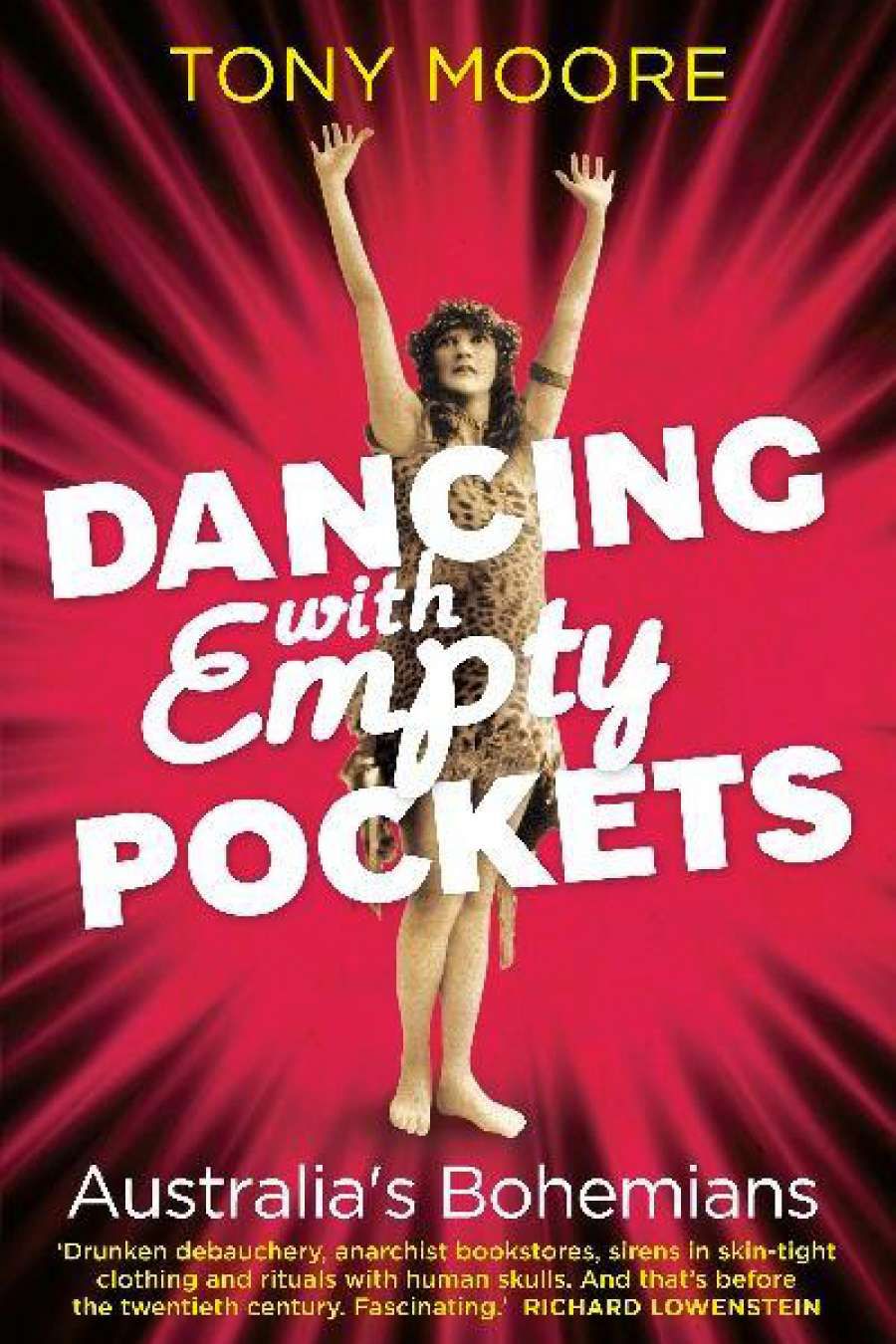

Tony Moore’s engaging account of Australian bohemians begins with Marcus Clarke and takes us through to Julian Assange. Along the way we encounter Australian bohemia in its diverse expressions, from the art of the Heidelberg School, writing of the Bulletin, high jinks of 1920s Sydney bohemia to the Sydney Push, Melbourne Drift, 1960s counterculture (in both its local and London expatriate manifestations), cultured larrikins of 1970s ‘new nationalism’, punk, post-punk, and much else. Here is the historian as impresario, assembling an extraordinary cast across 150 years of Australian cultural history. To bring them all together without producing an inedible stew is a major achievement in itself.

- Book 1 Title: Dancing with Empty Pockets

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australia's Bohemians since 1860

- Book 1 Biblio: Pier 9, $29.95 pb, 384 pp, 9781741961447

Moore begins by exploring the nineteenth-century European origins of the idea of bohemia in writing of French journalist Henri Murger. Bohemianism’s heroic image of the artist embodied a romantic revolt against bourgeois society and the market economy. Yet bohemia was itself a fragment of the middle class, and its writers and artists were participants in the culture market. Drawing on Pierre Bourdieu, Moore shows that the elevation of the bohemian artist to a status beyond ordinary mortals increased the value of what they had to offer in that marketplace. The supposed independence of artists from the market’s imperatives was intended to guarantee their work’s authenticity.

Moore’s treatment of Australian bohemianism in the context of the development of culture industries in a capitalist economy prevents this book from degenerating into a series of entertaining stories about colourful personalities or – a far worse prospect – a tedious account of intergenerational warfare. There is still plenty of colour; Moore has an eye for the telling anecdote and striking quotation. But it is bohemia’s relationship with the market in cultural goods – whether in the 1870s Melbourne of Clarke or Frank Moorhouse’s Sydney a century later – that ballasts the book. Many of its topics, after all, have been treated in their own right elsewhere, some on numerous occasions. Moore draws on this literature judiciously; to view each through the lens of bohemia illuminates them all in new ways.

Moore is alert to change, as well as to continuity and tradition. Clarke and his confrères saw themselves as exiles from Europe, and Clarke himself took on the persona of the flâneurin his writings on Melbourne. This bohemia emulated clubby English forms, whereas the next generation of bohemians associated with the Bulletin and the Heidelberg School combined cosmopolitanism with an interest in Australian distinctiveness. They emphasised – in a way Clarke and his friends did not – the romantic attraction of the bush as an escape from the modern city.

Some of these bohemians, such as Henry Lawson, were also closely associated with the labour movement; they forged a relationship with socialism and the working class that sat uneasily with bohemianism’s stress on the special status of the artist. What Moore calls the ‘larrikin carnivalesque’, while registering bohemia’s identification with the culture of the working-class male and its play with popular culture, was unpalatable to a large section of the respectable working class, a point that Moore doesn’t fully acknowledge. The Australian bohemian celebration of beer, gambling, and sex alienated a larger section of society than those ordinarily dismissed as wowsers.

Moore is sensitive to the changing place of women in bohemia. Absent from Clarke’s version of bohemia (except perhaps in a walk-on role as courtesans) and largely excluded from the pleasures of the fin-de-siècle artists and writers (except as artist models), the opening up of journalism to women from around the time of World War I helped secure some a place in bohemia. Dulcie Deamer, who graces the cover of this book in her famous leopard-skin costume, is the most famous example from this era, but she was not alone. Gender, moreover, continued to differentiate how men and women participated, whether in the context of the domestic bohemia of the Heide group of artists in 1940s Melbourne, the Push in 1950s Sydney, or the women of the 1960s counterculture. Even in the age of the contraceptive pill, sexual freedom had different implications for men than for women. The women of the Push might have been able to initiate sexual encounters in a way that was unconventional for the time, but they still had to endure abortions, even when they were funded by passing round the hat. Women’s status derived from their relationships with Push men: older Push men were able to acquire young Push girlfriends, while Push women, as they aged, were likely to move on, especially those with children. But the 1960s and 1970s unquestionably opened up new possibilities for bohemian women, with some – such as Germaine Greer and Lillian Roxon – establishing highly successful international careers in which they carried with them libertarian ideas associated with their Australian bohemia.

Dulcie Deamer, 1923. (photograph via State Library of New South Wales)

Dulcie Deamer, 1923. (photograph via State Library of New South Wales)

A book as ambitious in scope as this one will inevitably deal more satisfactorily with some topics than others, but Moore’s treatment of Roxon is a useful hook on which to hang one obvious weakness: his neglect of Brisbane. Brisbane does, inevitably, come into his story when he deals with popular music in the 1970s and beyond – with The Saints and the Go-Betweens, how could it not? – but that city’s role in Australian bohemia is otherwise handled uncertainly. Lillian Roxon is rightly associated with the Sydney Push, but she was from Brisbane and as a teenager had come into contact with the lively bohemian circles who frequented the Pink Elephant Café, figures such as Barrett Reid, Laurence Collinson, and Thea Astley, all associated with the magazine Barjai. It would be unfair and inaccurate to suggest that Moore’s account of Australian bohemia is a tale of two cities, but he is far less assured in dealing with the world beyond Sydney and Melbourne than he is in exploring their bohemian life. Did Perth and Hobart have bohemias? Is there more to bohemianism in Adelaide than Max Harris and Angry Penguins? (The history of male homosexuality in that city would suggest so.) And what of Canberra, with its unique concentration of diplomats, public servants, academics, students, and scientists in the 1950s and 1960s, including quite a few migrants from other Australian bohemias such as the Sydney Push?

Moore has had a diverse career in the media, publishing, and academia. There is probably no other Australian historian who can move across ‘high’, ‘popular’, and ‘middle-brow’ culture with such assuredness. His pleasure in the popular culture of his own times, from the Barry McKenzie films (on which he has written an earlier book) through Nick Cave to The Chaser team and Marieke Hardy, is obvious. But I also sensed that his bohemian lens began to move out of focus at this point. What, precisely, does the contribution of Steve Vizard to Australian comedy have to do with bohemianism?

This is a well-written book by an author who is not afraid to explain the past in terms that will help a contemporary audience get its bearings. Norman Lindsay is an ‘all-round multimedia libertine’. When Max Harris, as an eighteen year old, writes, ‘I am an Anarchist – So what?’, he has ‘all the venom of an antipodean Johnny Rotten’.

Moore has produced a major work of Australian cultural history, and, in view of its wide scope and lively style, one that deserves a wide readership.

Comments powered by CComment