- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

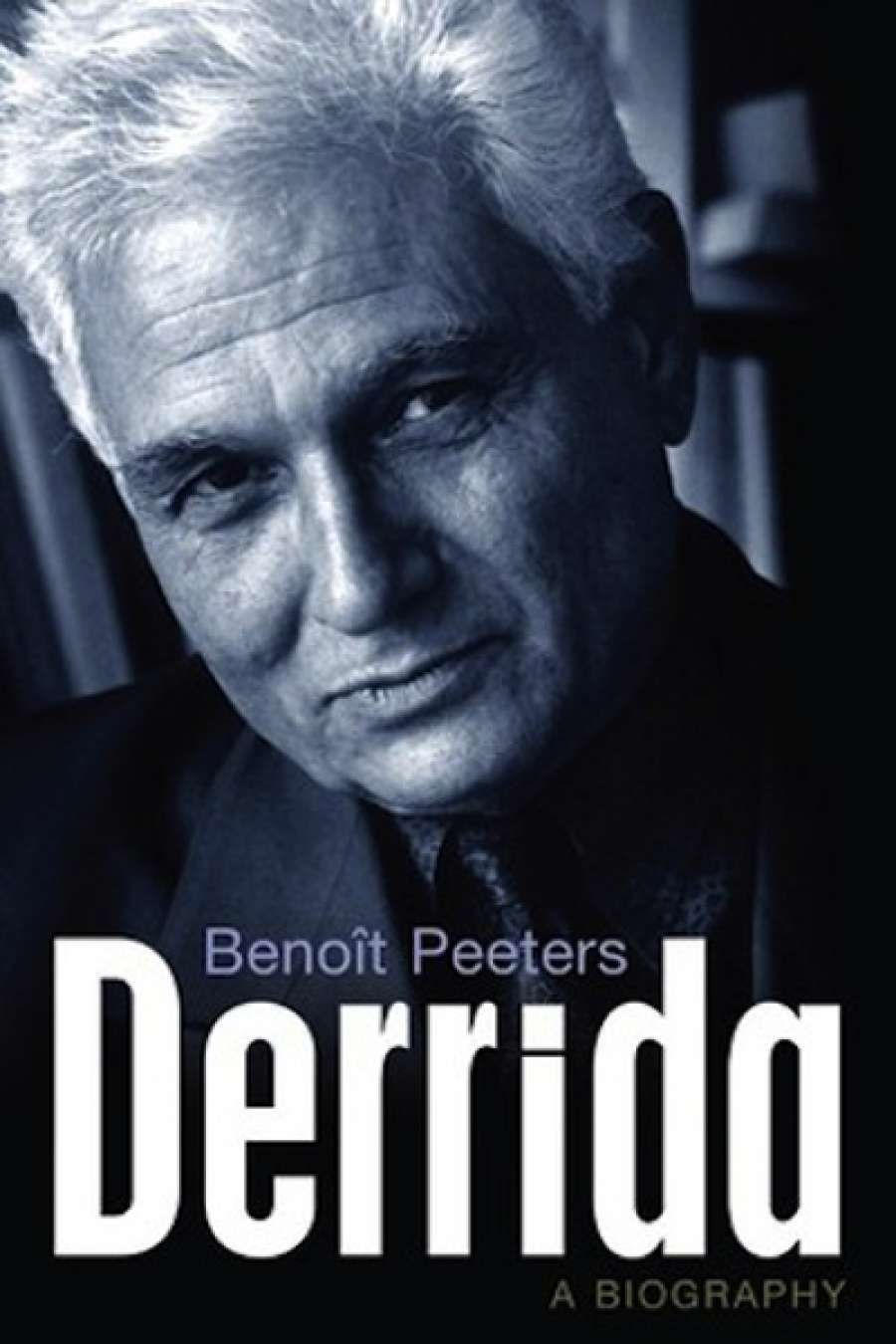

- Custom Article Title: Shannon Burns reviews a new biography of Derrida

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Derrida

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Biography

- Book 1 Biblio: Polity (Blackwell), $47.95 hb, 637pp, 9780745656151

So might a ‘Derridean’ biography of the controversial philosopher, academic, memoirist, literary/art critic, poet, and guru of Deconstruction commence. Fortunately, in this timely, even-handed biography, Benoît Peeters – novelist, comic book scholar, film-maker – avoids Derrida’s rigour (or conceit). Instead of exploring the foundations of biographical discourse via a genealogical survey, or interrogating the conditions of writing an ‘authorised’ biography before addressing its subject, Peeters takes the direct route. ‘Without denying the interests of such an approach,’ Peeters writes, ‘I have sought, in the final analysis, to write not so much a Derridean biography as a biography of Derrida. Mimicry, in this respect as in many others, does not seem the best way of serving him today.’ Indeed, the ‘mimicry’ of Derrida that constitutes much of ‘deconstruction’ as a critical mode is given short shrift throughout.

Derrida, translated from the French by Andrew Brown, is the first comprehensive biography of its subject. Born in 1930, Jackie Derrida was the youngest child in a fairly typical Jewish-Algerian family living in the suburbs of El Biar. According to Peeters, Derrida was nicknamed ‘the Negus’ in his youth due to his strikingly dark skin; this and other early signs of difference made a deep impact. The most significant of these would influence Jackie’s fraught relationship with institutional education for many years to come: when the Vichy régime’s colonial front zealously enforced anti-Semitic policies in Algeria, Derrida – a good student – was expelled from hislycée until the end of the war. To make matters worse, he was forced during this period to attend a Jewish school, which he loathed. Derrida later attributed these two, linked experiences – forced exclusion and forced inclusion – to his subsequent ‘incapacity to enjoy membership in any kind of group’.

After deciding on a career in philosophy in his teens, Derrida went to boarding school in Paris, and there endured the many excitements and bouts of melancholy typical of a displaced provincial student. Letters to a friend from this period suggest a near-suicidal depression, and excessive doses of amphetamines and sleeping pills failed to neutralise academic anxieties.

Jackie’s temperament often got in the way of success at university. Asked to analyse a mundane passage from Diderot, he invented his own version of the text, one with ‘a range of meanings fanning out from each sentence’ instead of simply highlighting the obvious, as expected. After one examiner chided Derrida for ignoring the text’s explicit content, Jackie declared: ‘Explicitly, this text doesn’t exist; in my view it has no literary interest.’ His analysis supplemented the lack; the ‘birth of the reader’ had already been accomplished.

His close (mis)readings of seemingly incidental passages, word or phrase repetitions in major philosophical works, combined with extensive (and often digressive) analyses of occasional texts, soon forged a daunting reputation. Compelling but highly specialised and idiosyncratic critiques of Foucault, Levinas, Rousseau, and Lévi-Strauss made Derrida’s name in philosophy in the mid- to late-1960s. Even Bernard-Henri Lévy, with whom Derrida once famously came to blows, granted that, ‘Derrida’s solitary and obstinate labour is already part and parcel of the great tradition of philosophies of the hammer.’ Lévy added: ‘In the fairground of ideologies, the Derridean hammer is perhaps one of our criteria of rigour.’ This philosophical rigour coincided with a series of interventions in the sphere of literary criticism. As Roland Barthes notes:

Derrida was one of those who helped me to understand what was at issue (philosophically, ideologically) in my own work: he knocked the structure off balance, he opened up the sign: for us he is the one who unpicked the end of the chain. His literary interventions … have been decisive, and by that I mean: irreversible.

After graduating from university, Derrida became a secondary school teacher for a short, miserable period before accepting his first academic position at the école normale supérieure. A generously attentive and available lecturer, he was much admired by students, although they had good reason to be wary, since sympathy for Derrida’s brand of philosophy could damage a graduate’s prospects within the university.

Over the years, Derrida was involved in several institutional scuffles in France and abroad. Cambridge’s decision to award him an honorary degree was met with outrage among those who found his work obscurantist, and major publications like the Times Literary Supplement and The New York Review of Books were, says Peeters, generally hostile.

The precise nature of Derrida’s contribution to philosophy and culture remains unclear, despite the proliferation of deconstruction-inspired journal articles over decades, not to mention his sizeable influence on post-colonial studies, gender studies, queer studies, and minority politics via figures like Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Homi Babha.

Derrida was convinced that it was no longer possible to construct ‘a big philosophical machine’; he preferred to proceed, instead, by a series of ‘oblique little essays’, and a recognisable brand of obliquity may be Derrida’s most enduring legacy. Like Walter Benjamin before him, Derrida privileged the fragment and sought to bring marginal objects into fruitful, if uncomfortable, theoretical and poetic relations.

‘Like Walter Benjamin before him, Derrida privileged the fragment and sought to bring marginal objects into fruitful, if uncomfortable, theoretical and poetic relations.’

According to Peeters, Derrida saw deconstruction as ‘a way of thinking about philosophy’, instead of a distinct philosophical system or rigid method in itself. It was a genealogical means of revealing philosophy’s ‘concepts, its presuppositions, its axiomatics, and doing so not only theoretically but also by questioning its institutions, its social and political practices, in short the political culture of the West’. The fact that such a resolutely ‘untimely’ thinker – a critic of structuralism when it was at its zenith, a loyalist to philosophy in an age of cultural studies, and a Joycean – could have inspired anything resembling a faddish critical industry is worthy of intensive analysis; for his part, Peeters tends to blame this quirk of fate on the misunderstandings of Derrida’s followers, particularly in the United States.

Derrida is conventional biography at its serviceable best. Peeters fluently sketches his subject’s many sides: a Marxist sympathiser but not a communist; a philosopher with an unyielding passion for literature; a melancholic joker and sometimes-hypochondriac; a lover of mafia stories and mainstream cinema; an anxiously affectionate but distant parent; a faithful but emotionally volatile friend; a ‘radiant narcissist’ and erratic driver; and, in Derrida’s words, a ‘vegetarian who sometimes eats meat’.

Of his private life, we learn that Derrida was not at all domestic by nature. His wife, Marguerite, took care of all practical matters at home, attending to financial affairs and raising the children. It was little wonder, therefore, that despite Derrida’s reputation as a ‘compulsive seducer’ (a long affair with Sylviane Agacinski produced a son in 1984), he considered their marriage to be ‘unbreakable’.

Peeters also details the important phases of Derrida’s public life, including his explosive impact on American universities, his affiliation with the Tel Quel group and its rupture, as well as a farcical arrest for drug trafficking in Prague in 1981. The controversies linking deconstruction to Martin Heidegger’s Nazism and Paul de Man’s anti-Semitism are handled soberly, and the major books and essays are neatly contextualised. Derrida’s political radicalisation in later years, and an increasing interest in the humane treatment of animals is also, thankfully, given adequate consideration.

And there are cheap thrills aplenty. Gulping down the details of Derrida’s public and private relations with figures like Louis Althusser, Emmanuel Levinas, Hélène Cixous, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Michel Foucault, Paul Ricoeur, Pierre Bourdieu, Gilles Deleuze, Alain Badiou, Michel Tournier, Philippe Sollers, Julia Kristeva, Maurice Blanchot, Jean Genet, Roland Barthes, Paul de Man, Gayatri Spivak, Jean-François Lyotard, Jean-Luc Nancy is bound to prove exciting for those who have laboured over twentieth-century French theory and literature. Such readers will also delight in the image of a young Derrida posing with bow and arrow (for a photograph ‘dedicated to one of his girlfriends’) or, later, starring in a priceless tableau vivant of The Massacre of the Innocents.

This linear, ‘hierarchical’, and accessible biography owes much to Derrida’s extensive archives, as well as to interviews with family, colleagues, and friends. Given that Derrida’s handwriting is said to be unreadable, and even his polished work can seem encrypted, Peeters deserves high praise for interpreting and arranging a vast cache of letters, notes, drafts, and testimonies into a lucid and absorbing narrative.

Comments powered by CComment