- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Calibre Prize

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Because it’s your country

- Article Subtitle: Bringing back the bones to West Arnhem Land

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The morgue in Gunbalanya holds no more than half a dozen corpses – and, as usual, it was full. When the Old Man died in the wet season of 2012, they had to fly him to Darwin, only to discover that the morgue there was already overcrowded. So they moved him again, this time to Katherine, where they put him on ice until the funeral. The hot climate notwithstanding, things can move at glacial speed in the Northern Territory, where the wags tell you that NT stands for ‘Not today, not tomorrow’. The big departure had stalked and yet eluded the Old Man in recent years. Now he would wait six months for his burial. Only then would he be properly ‘finished up’, as they say in Gunbalanya, a place rich in many things: poverty, and euphemisms for death, among them.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

Listen to this essay read by the author.

The morgue in Gunbalanya holds no more than half a dozen corpses – and, as usual, it was full. When the Old Man died in the wet season of 2012, they had to fly him to Darwin, only to discover that the morgue there was already overcrowded. So they moved him again, this time to Katherine, where they put him on ice until the funeral. The hot climate notwithstanding, things can move at glacial speed in the Northern Territory, where the wags tell you that NT stands for ‘Not today, not tomorrow’. The big departure had stalked and yet eluded the Old Man in recent years. Now he would wait six months for his burial. Only then would he be properly ‘finished up’, as they say in Gunbalanya, a place rich in many things: poverty, and euphemisms for death, among them.

The Old Man’s name is indelibly associated with Gunbalanya, a settlement on the western border of the great Aboriginal reserve of Arnhem Land. But it is a name that cannot be used. In northern and central Australia it is customary, as a sign of respect for the dead and those who loved them, to avoid uttering the name of the deceased. The taboo on naming derives from a wider process of purging that traditionally occurred at the time of death. In earlier times – and sometimes even today – the possessions of the deceased were quickly burned or disposed of in other ways; the initial rites of grieving, involving preliminary treatment of the body, were rapidly performed; the site of death was abandoned. The transition to a more sedentary way of living means that it is no longer so simple to shift camp, while the high mortality rate, compounded by the financial impost and logistical complexities of assembling the necessary mourners, has resulted in an almost farcical backlog of funerals. All of this contributes to the interminable prolongation of ‘sorry business’. Nobody likes it, but no one knows how to change it.

When people die, their house and the other places they frequented are treated with the pungent smoke of green ironwood leaves. The persons close to them, and those who handled them after death, are also smoked. Smouldering boughs are brushed against the torsos of these mourners; alternatively, they stand near a fire and fumes are wafted about them. The purpose of these rites is to decontaminate the living from their contact with the dead and to protect them against the spirit who, at this transitional moment, might be confused, angry, mischievous, or worse. The great changes of the past century have done little to diminish the potency of the spiritual realm, from which a person emerges at the time of conception and to which they return when mortal life has ended.

The conventions require that I do not name directly the Old Man, whose last great work is the subject here. Formally, he is referred to by the ‘death name’ chosen by his relations: Nagodjok Nayinggul. But I will refer to him by the more familiar ‘Wamud’. This is the ‘Bininj way’ – the way we would speak of him if we were in Gunbalanya now. Bininj is the word for ‘man’ in the Kunwinjku dialect of the local language, Bininj Kunwok. The Aboriginal people of the west Arnhem region use it as a generic descriptor for themselves. Wamud was the Old Man’s skin name; I addressed him as such even when he was alive. This is customary among Bininj, who generally avoid using a person’s name in their presence, preferring instead terms of address that affirm the kin relationships that bind everyone together. Wamud often called me ‘Bulanj’. That is my skin name, given to me by another old man, Kodjok, when he made me his classificatory son. That was his skin name, and I must refer to him as such, for just a week before Wamud’s long-awaited funeral Kodjok himself ‘finished up’.

While anthropologists, when they first encountered these sorts of classifications, tended to emphasise their rigidity, the kinship system is in reality highly adaptive, as is evident in the practice of giving skin names to outsiders, who are thereby positioned in the local taxonomy and, it is hoped, integrated to some degree into the network of reciprocal obligations that are at the core of Bininj sociality.

Cahills Crossing, East Alligator River

Cahills Crossing, East Alligator River

(photograph by Adis Hondo at the request of Wamud)

The taboo on naming extends to representations of the deceased person, including photographs, films, and voice recordings. Contrary to popular belief, the taboo is temporary. As time passes and mourners become reconciled to their loss, the person’s name and image are permitted to resurface. How long this takes varies considerably. The age and status of the deceased have great bearing on the matter. In Wamud’s case, it will be some years until the people of Gunbalanya speak of him again by his ‘true’ name. He was a pre-eminent figure and an acknowledged leader, not only among Bininj but also among Balanda – as white people are known in Arnhem Land. When speaking (or writing) there is no restriction on telling stories about the man whom we call Wamud: it is the naming of him that is the problem. Even at his funeral (held in an overflowing Anglican Church in Gunbalanya in June 2012), extended eulogies were delivered and the memories encouraged to flow.

My contact with Wamud, which began in 2006, was all to do with memories and their preservation. Historic films and sound recordings, made in Gunbalanya in 1948, were the impetus for my visiting the area. Equipped with digital copies of these films and records, which were originally intended for anthropological study, I hoped to interpret them with the true experts: their traditional owners. Produced during a postwar extravaganza known as the American–Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land, the films and recordings had been archived in collections in Sydney and Canberra. While study of them marked the beginning of our acquaintance, Wamud and I became friends more recently when we were entangled in some film-making of our own. That footage I can revisit privately, but it cannot be made public until the mourning period has ended. Inevitably, the footage shapes my impressions of him, even as I try to separate the diminished, although still marvellously lucid, figure recorded by the camera from the charismatic and physically robust individual whose eyes sparkled with astonishment when, on that first meeting, he was asked if he would like to see some film of the initiation ceremony known as the Wubarr.

‘The great changes of the past century have done little to diminish the potency of the spiritual realm’

Back in 2006, as a new chum to northern Australia, I was fortunate in having as a guide and tutor the linguist Murray Garde, a fluent Kunwinjku speaker, who is intimately versed in cultural protocols. Ceremonial knowledge in Arnhem Land is deeply gendered, and the Wubarr is exclusive to men. To escape the gaze of unauthorised eyes, we retreated to the edge of town and set up my laptop in the hut of another old man, a distinguished painter, who is now also finished up. He and Wamud were close to tears by the end of the film. Much of the emotional impact of the material is due to the breakdown of localised ceremonial traditions, of which the Wubarr was a key example. For reasons not easily explained, performances of Wubarr became ever more occasional from the 1950s. By the 1970s it was defunct. This was not because male initiation had died out, as it has elsewhere in Australia; in west Arnhem Land it continues to this day. Instead, Wubarr was displaced by the pan-regional Kunapipi ceremony, a very different rite, dedicated to the Rainbow Serpent, which would emerge as the dominant mode of initiation. For Wamud, watching the old footage rekindled memories of the exquisite dance and music at the heart of the ceremony, and of his old teachers, finished up long ago, who had inducted him into the rite.

After Wamud had seen the footage, he dictated a statement in Kunwinjku that Garde has since translated, asking that he be given access to this and kindred documentation:

Today I have been shown the movie of the Wubarr ceremony taken a very long time ago, and so I wanted very much to see this. I was a young boy at the time and so I would like you very much to be able to make it [an edited copy] for me, so that in quiet times when I am not working, I’ll go back to my camp and watch the images. It will make me reflect on all I know about that Wubarr ceremony and how at that time it was close to disappearing. Today that ceremony is gone, it lies buried forever. And so seeing that movie brought it back to mind again. Who can we find today who knows about that ceremony? A few of us know, but those old people are all gone now … I would like to hold on to it. Myself and the other senior men here, we would share it together and gather together to watch it. We will watch to see how all those years ago, we were initiated by those old people into that Wubarr ceremony. If we don’t see this film again, we won’t be able to remember. Maybe all we would have is a name. The Wubarr ceremony has come alive again in those images they made. That is all.

Four years passed, and my excavation of the archives generated by the 1948 expedition continued. A trip to Washington yielded a significant cache of films and photographs – of Wubarr and many other aspects of the Bininj world. In 2010, when Wamud expressed interest in making a film, it was clear that he had little hope of seeing it in its finished state. He had cancer, diabetes, and more. As he admitted, beer, cigarettes, and rough living had taken their toll.

We all spoke of him as the Old Man, this being respectful in a society where advancement in age confers prestige rather than irrelevance. But Wamud was hardly old by most people’s standards; I doubt that he was seventy. It is hard to be certain, for he was born in the bush, where births went unrecorded. He was a baby when his family came in to Gunbalanya, then known to the wider world as Oenpelli Mission. Of course, by the standards of his own community Wamud was an old man. Indigenous life expectancy in the Northern Territory is even bleaker than it is in the rest of Australia. Territorian males who are Aboriginal can expect to live 61.5 years, compared to 75.7 for their non-Aboriginal contemporaries.

With his raft of health problems, Wamud was heavily medicated and suffering excruciating pain. Cruel indignities had been inflicted on his once towering form, perennially crowned by a black cowboy hat. The hat remained while its wearer shrank. His attenuated physique, skeletal in its wheelchair, formed a surreal contrast to his face, lightly whiskered, devilishly handsome, and still exuding the playful quizzicality of earlier years. Infirmities notwithstanding, Wamud inhabited his body with the same ease that he must have borne as a mature, initiated man in his physical prime. An operation had reduced his right foot to an ugly stump, but he made no attempt to hide it.

Old Wamud knew that he was racing against time when he poured what he could of his precious energy into making the film. His motives for doing so were in a way obvious. He wanted to leave a record for future generations. I guess he knew that the footage would be suppressed during the mourning period and that eventually it would resurface. Characteristically, he was never a passive subject during our filming sessions, and I now realise that he was thinking very laterally about the type of personal record that he was leaving. This is apparent in the hours of interview material that are presently embargoed, although it is more overt in other footage, filmed at his instruction, in which he doesn’t appear.

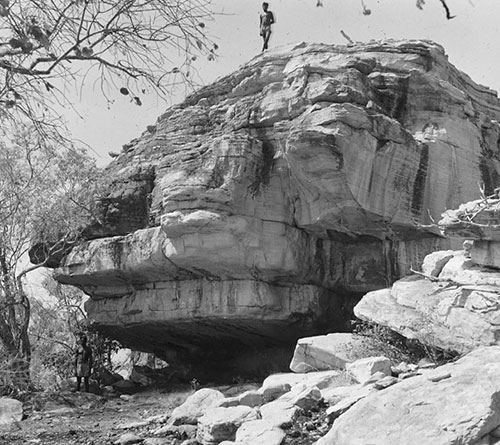

On the first day of what would be our last shoot with him, in July 2011, Wamud asked to be taken through his ancestral country, west of Gunbalanya, to the East Alligator River. I was driving with him in the passenger seat. Adis Hondo, the cinema-photographer with whom I collaborate, and SuzeHoughton, our sound recordist, sat in the back. At the causeway known as Cahills Crossing, Wamud asked Adis to get out and film the water. The river is the border between Kakadu National Park (which Wamud had helped establish) and the vast patchwork of Aboriginal homelands that is Arnhem Land. You can make what you like of Wamud’s directive that we film the river. Paying homage to ‘this beautiful country’, as he often called it – picturing, singing, honouring it – was always paramount. Clearly, filming the country was a way of marking his territory. But the more I look at the footage – the vegetation moving subtly with the breeze; the rush of water through the frame – it acquires a portent that I never perceived when I stood with Adis by the tripod, and not only because the river, almost too obviously, is a symbol of life.

Although located some fifty kilometres from the coast, the East Alligator is tidally affected at Cahills Crossing. With the assault of an incoming tide, the river promptly changes direction and within minutes the formerly innocuous causeway becomes impassable. A channel that flows in both directions, a saltwater phenomenon in freshwater country, it recalls the belief, common to various Aboriginal cultures of the northern coastline, that the recurrent transition between life and death, between mortal and spiritual existence, is manifest in the ebb and flow of the tides. It is not, I think, so very far-fetched to find a portrait as well as a landscape in that footage of the ever-moving river, a site in which death as much as life is a creative force. As I look at that footage, which during Wamud’s lifetime I would have been inclined to use for nothing more than the odd cutaway in our planned documentary, I find it suffused with his presence, although he sits outside the frame.

One year earlier he had pointed out a shallow sandstone overhang where human bones lay piled in the dirt. He wanted us to film them and later spoke of them not as bones, but as a ‘man in his country’. This is relevant, for it was the restoration to their country of just such men and women that constituted Wamud’s last great work.

Wamud’s country near the East Alligator River

Wamud’s country near the East Alligator River

Outwardly dishevelled and chaotic, the larger Aboriginal settlements like Gunbalanya are usually composed of a network of smaller communities, referred to as ‘camps’. Kodjok lived in Argaluk Camp, so called for its proximity to a boulder-strewn rise called Argaluk, a site of ceremonies. Wamud lived in Banyan Camp, named after a banyan tree of special significance. The designation ‘camp’ suggests that even now, more than a century after the pioneer buffalo shooter Paddy Cahill began farming and developing the site that would later fall into the hands of missionaries, the town has a transitory or provisional status, though for many occupants this mobility is more a dream than a reality. Few Bininj own vehicles, so it is difficult to travel to Darwin, to distant ceremonies, or to the small camps or clusters of huts that constitute the outstations (tiny settlements on often isolated homelands).

Numbering 1171 inhabitants according to the 2011 census, Gunbalanya is a large settlement by Arnhem Land standards. It offers some employment and other attractions: two shops, a meatworks, an art centre, clinic, school and, controversially, a ‘sports and social’ club, licensed to sell alcohol. Wamud was a regular at this institution, and took pride in having played a role in its establishment.

Wamud shared his house with his wife (who has passed away and cannot be named) and an indeterminate number of younger relatives. It was a metal construction, green in colour, no more or less dilapidated than those around it. The carcass of a four-wheel drive had made of the yard its final resting place. When Wamud’s energy allowed, I worked with him on the verandah. It was there that he and I watched a movie, copied from the National Geographic Society film archive, that shows the bones being stolen. That Aboriginal human remains were fetishised and collected in the name of science, and often taken to institutions in distant lands, is hardly breaking news. But the idea of bone-taking being captured in a National Geographic film production – in colour no less – shocks me even now. As with other inconvenient realities, ranging from land theft to massacre, there is a tendency to compartmentalise bone-taking as a predilection of the nineteenth century, when, as the film shows, it was nothing of the sort.

We first see the bone taker reaching into the hollow of a crevice; his rear end, protruding towards the camera, is stained with channels of sweat. Then, turning to face us, he unwraps a jawbone from a blackened shred of rag – evidence, one would think, that it is hardly of great antiquity. Bespectacled, and with lips pursed beneath a trim moustache, his officer’s deportment is upset by a slash of blue headband that gives him an air of piratical craziness. He adds the jaw to a wooden crate already full of arm and leg bones, butted up against a skull.

The bone taker’s diary, which I have read closely, makes it plain that the presence of the photographer was prearranged. Built into the act of seizure was the attempt to transcend its fleetingness. Perhaps in an attempt to give it scientific import, the archaeologist and the cameraman made of the theft a pedagogical performance. We can see the archaeologist lifting and handling the skull he has taken, pointing out distinctive features, and then slotting the jaw in place and presenting to the camera its largely toothless grin. The final seconds of the sequence show a glimpse of scenery from the top of Injalak hill, which, for any local, is immediately identifiable as the site of the theft. There is a body of water, a yellowed strip of land, a few scant dwellings. We are looking, of course, at an earlier incarnation of Gunbalanya where, some sixty years later, Wamud and I sat on his verandah, grimly watching the spectacle on my laptop. The footage ends when the archaeologist and an assistant (a white man not seen until now) cross the frame and clamber downhill. Manhandling the now lidded crate, they disappear from the picture.

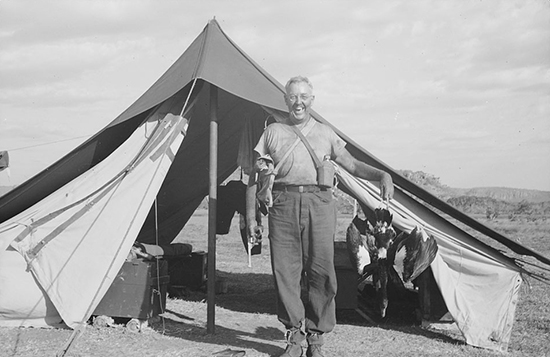

The diary records that the film was taken on 28 October 1948. The cameraman was National Geographic Magazine photographer Howell Walker and the archaeologist was Frank M. Setzler, head curator of anthropology in the United States National Museum (now the National Museum of Natural History), a division of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. They were visiting the region as members of the American–Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land. Just five days before Setzler took the bones, he and his fellow researchers had enjoyed the considerable honour of being admitted to the Wubarr ceremony, thereby producing the film and sound recordings that so enthralled Wamud and the other old men.

The expedition was a large-scale research venture involving fifteen men and two women that roved through Arnhem Land for much of 1948. Somewhat propagandist in intent, its chief supporter within the Chifley government was the America-friendly Arthur Calwell, who, before he acquired the immigration portfolio, served as minister of information. He was a great supporter of the Adelaide photographer cum ethnologist Charles P. Mountford, who led the expedition. Mountford had been lecturing in the United States in the last year of the war when he came to the attention of the National Geographic Society and the Smithsonian. He persuaded them to sign up with the Commonwealth of Australia as official partners in the expedition, a seven-month anthropological, natural-history, photographic, and film-making adventure, intended as an overt display of bilateral friendliness. Needless to say, the inhabitants of Arnhem Land were never consulted about its visitation to their country.

Jimmy Bungaroo asleep, 1948. Photograph by Frank M. Setzler. Photo Lot 36 (oenpelli_142), National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Jimmy Bungaroo asleep, 1948. Photograph by Frank M. Setzler. Photo Lot 36 (oenpelli_142), National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Setzler’s excavation of mortuary sites, conducted in various parts of Arnhem Land, is thoroughly documented in the official records of the Arnhem Land Expedition and in his private papers. The latter are particularly incriminating, in that they candidly record the ruses to which he resorted in order to avoid the scrutiny of locals when he took the bones. Two young men, Jimmy Bungaroo and another identified only by his mission name, Mickey, had been assigned to Setzler as archaeological assistants. His diary records that on 9 October 1948, accompanied by one of these men, he entered a large cave on Injalak where a skull and numerous long bones, all coated with red pigment, were visible. Setzler wrote: ‘I paid no attention to these bones as long as the native was with me.’ On 28 October (the same day he filmed with Walker, although this appears to have been a separate incident), he writes of Bungaroo and Mickey:

[d]uring the lunch period, while the two native boys were asleep, I gathered the two skeletons which had been placed in crevices outside the caves. These were disarticulated … and only skull and long bones. One had been painted with red ochre. These I carried down to the camp in burlap sacks and later packed in ammunition boxes.

Setzler’s surreptitiousness leaves little doubt of his awareness that, even by his own standards, this was theft. Yet he took something else when he stole the bones: a photograph of Bungaroo, soundly sleeping on his bed of rock. He is dressed only in a naga (loin cloth) and near the lower margin of the photograph are his pipe and tobacco tin, a reminder that those who laboured for the expedition were mostly paid in tobacco. Why Setzler photographed the sleeping youth is not explained. He did caption it minimally: ‘Jimmy (Bungaroo), my native assistant from Goulburn Island asleep on a rock.’ Perhaps he took it to illustrate the tale of how he outwitted the natives when the bones were won. Or perhaps this furtive gesture was a mere extension of the trophy-hunting exhibited in his broader quest. Because the sleeper could not authorise or in any way control his portrayal, the photograph displays with rare lucidity the power relations that existed between him and the photographer. Yet as much as it objectifies the youth, the eroticism of the image is unavoidable. Bungaroo is beautiful in his tranquillity. The sense of desire that saturates this image can (and perhaps should) be read sexually. Yet it also speaks of the likelihood that a hoarder of the dead will see in the living the dead of the future. That is why this photograph is such a powerful expression of the bone taker’s gaze.

Mickey and Bungaroo (photograph by Frank M. Setzler). Photo Lot 36 (arnhemland_94), National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

Mickey and Bungaroo (photograph by Frank M. Setzler). Photo Lot 36 (arnhemland_94), National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

The battle to get the bones back is too long a story to tell here in its entirety. It took about a decade from the late 1990s, involved lobbying at an intergovernmental level, and provoked enormous hostility from certain factions at the Smithsonian, particularly within the National Museum of Natural History, an institution deeply divided about the status of its large transnational collection of human remains. What concerns me here is the perspective of people, including Wamud, who had to grapple not only with the hurt caused by the theft of the bones but also with the considerable challenges posed by their return.

The repatriation of the Arnhem Land remains occurred in two instalments. Initially, the Smithsonian would only release two thirds of the bones collected in 1948, citing an original agreement, brokered by Mountford, that all the collections amassed by the expedition were to be split at the ratio of two thirds to one third, with Australia, as the host country, the major recipient. Since the entire stock of human bones had been exported to Washington at the end of the expedition, the Smithsonian felt justified in releasing the two thirds in 2009 – an outcome that was by no means acceptable to the traditional owners.

Later that year, the Arnhem Land Expedition was the subject of a symposium at the National Museum of Australia. The Smithsonian’s insistence that it would keep in perpetuity the final third of the human remains was the subject of heated debate, and Thomas Amagula, a delegate from Groote Eylandt, issued a feisty press release comparing the Smithsonian’s retention of his ancestors’ bones with the US government’s efforts to repatriate its own servicemen who had died abroad. Kim Beazley, then ambassador-designate to Washington and a speaker at the symposium, issued a statement that he would personally lobby for the return of the bones when he reached the United States. Negative press coverage resulting from the symposium seems to have shamed the Smithsonian into voluntarily releasing the remaining third of the bones. This second repatriation took place in mid-2010. With Adis Hondo and camera, I travelled to Washington to document the homeward journey. Representing the localities from which bones were stolen were Joe Gumbula, a senior Yolngu man who spent his early years on the island of Milingimbi, Thomas Amagula, and Victor Gumurdul from Gunbalanya. To the bones they had a double duty: to both bring and sing them home.

The National Museum of Natural History and other major galleries and museums that comprise the Smithsonian Institution are situated along the Mall: an almost sacred axis through the heart of DC, commencing at the foot of the Capitol and ending at the George Washington Monument. It was not the location offered to the visitors from Arnhem Land to ceremonially receive their ancestors’ remains. That happened in the town of Suitland, a drab little satellite of the capital where the real estate is cheap and where the Smithsonian, when it outgrew its storage space in the downtown area, built climate-controlled facilities to warehouse collections. The premises are heavily guarded and encircled by an unscaleable fence. Suitland is ‘A CARING COMMUNITY’, according to the road sign, but when, a few years ago, I was going there daily to research the Arnhem Land collections, colleagues warned me that as a white visitor to a neighbourhood that is desperately poor and ninety-three per cent African American, I should watch my step.

Setzler holding a magpie goose (photographer unknown). Photo Lot 36 (oenpelli_127), National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

Setzler holding a magpie goose (photographer unknown). Photo Lot 36 (oenpelli_127), National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

The gated world of the Smithsonian compound, barricaded against the racial-political reality of its own doorstep, was an apposite locale for the ceremony that heralded the dispatch of the bones, which curators had packed in cartons that I came to think of as the ‘cardboard coffins’. Ceremonies in the museum world are generally to do with openings, bequests, or major acquisitions. But here we had come to celebrate, if that’s quite the word, a less publicised aspect of the museum business: the departure of objects from collections – known as ‘de-accessioning’ in curatorial jargon. I say ‘objects’ with a sense of reservation. Objects, after all, are things, whereas coffins – even if they are only cardboard boxes – are containers of people.

‘Setzler’s surreptitiousness leaves little doubt of his awareness that, even by his own standards, this was theft’

There were four cardboard coffins, each draped by an Aboriginal flag. Wheeled from the Smithsonian premises on a trolley, they led a stream of diplomats, officials, and hangers-on, gathered to honour their departure. Kim Beazley, now ambassador, and Native American employees of the Smithsonian, who warmly supported the Arnhem Land visitors, had spoken movingly. Now outside, as clapsticks pounded like a heartbeat, Joe Gumbula ignited a handful of leaves, harvested from a Washington gum tree, and the smoking phase of the ceremony began. There were fifty or so of us milling around in the sunshine. We were a mourning party, for this was, after all, the beginning of a very long funeral. Gumbula, as the elder figure among the three Arnhem Landers, had performed from a repertoire of mourning songs, traditional to north-east Arnhem Land. The light was exquisitely limpid on that northern summer day. A pair of armoured helicopters flew overhead, like hornets intent upon their destination. That was the president and his ubiquitous decoy, someone explained.

The bones travelled with us from Washington to Los Angeles, and from Sydney to Darwin. Adis and I flew on to Gunbalanya with Victor. It was at that point that our work with Wamud really began.

Beliefs about reincarnation and the origin of spirits among the Gagudju (Kakadu)-speaking people of Gunbalanya were described by the anthropologist Baldwin Spencer, based on his fieldwork of 1912. As he explained it, the people of the present are reincarnations of the first people who inhabited the country. The spirit, known as the Yalmaru, has a cyclical existence, treading back and forth between the worlds of the living and the dead. When a person dies and the mourning ceremonies take place, the Yalmaru watches over the bones in a role of guardianship. With the passage of time, the Yalmaru divides into two parts. One half remains the original Yalmaru; the other is a discrete though inextricably connected entity, named Iwaiyu. ‘The two are distinct and have somewhat the same relationship to one another as a man and his shadow, which, in the native mind, are very intimately associated,’ according to Spencer.After a long period of watching over the bones, the time comes to reincarnate. Iwaiyu assumes the form of a frog who, with Yalmaru’s aid, finds and enters a woman. Iwaiyu develops into a baby and in this way the spirit returns to the domain of the living while retaining a presence in the world of the dead.

Isaiah Nagurrgurrba gathers paperbark to wrap the bones

Isaiah Nagurrgurrba gathers paperbark to wrap the bones

Contemporary beliefs in Gunbalanya, as Wamud explained them, do not exactly equate with Spencer’s account. Much has changed in the past century and Wamud’s family is among the few that can claim lineage with the Gagudju, whose estates lie to the west of the town. Christian influence has had an effect here, but in the syncretic cultures of Arnhem Land, the Bible can be treated as a belief system that sits alongside, rather than overriding, the Aboriginal traditions. So, despite the many changes dating from the twentieth century, there are significant areas of continuity between the beliefs articulated by Spencer and those of today. Pre-eminent among them – and this applies to much of Aboriginal Australia – is the ongoing relationship between a person’s spirit and their physical remains.

When seated near the cave with the ‘man in his country’ whom he wanted us to film, Wamud explained to the camera the importance of being put to rest within one’s territory after death. He explained that, in earlier times, the body of the deceased went through various stages of processing. First, it was put on a platform constructed in a tree and covered in skins or, more recently, blankets. Later the bones were transferred to an elaborately painted hollow-log coffin, planted upright in the ground. This was part of the funeral rite known as Lorrkkon. Much later, the bones were removed and installed in caves or crevices. Wamud explained:

They would get all bones, they would paint them in either yellow or red ochre, and then they would take them up onto the hill and put them in cave and they would say to them … in language: ‘I’ll leave you here,’ and talk to them, and then they would tell them, ‘Look I’m following you, I’m coming too, so wait for me.’ And they would put them to sleep then in their own country, in their own territory. Doing all that first, putting someone in the cave, doing that, that was the main traditional owner in there, or elderly person, who was the last one, and then [the] next one took over, maybe his son, and then it went on ... [We do it] not because we love you and we leave you here but because it’s your country, we’ll come back to you and we’ll call out for help if you can help us…

Having the bones here it means that you’ve got the man still staying in his own territory … I can call to him any time because I know he’s here. No other questions … I know he’s here, I go to that cave and call out for help. Like somebody might be in danger. That’s when you really need someone. So the traditional owner would help and in spirit they would still help.

What I have come to realise, in talking about these issues, and in being taken to sites where remains were stolen, is that the dead never become objects or object-like. This is a fundamental contrast to the Judeo-Christian tradition, where death marks a rupture between flesh and spirit; where the soul goes elsewhere. In west Arnhem Land, the precise relationship between spirit and bones is never easily expressed, perhaps because of the limits of my questioning or understanding, because of the linguistic differences, or because there is a range of beliefs about such matters. Most likely, it is a combination of them all. One reason why the behaviour of spirits is not readily pinned down is because spirits have agency. Like living people, they can be kindly or malicious; friendly, dangerous, or merely indifferent; healers or spreaders of disease. Accidents or mishaps are often attributed to spirits wreaking mischief. Care is required, even in what you say about them.

As I understand it, spirits live in proximity to bones, though they are not embodied within them. Spirits and bones are intimately related. Although one is immaterial and the other material, neither will perish. The living and the dead coexist. In this place-based cosmology, it is only natural that a person’s bones should be laid to rest in their ancestral estate. For Bininj, the actions of Frank M. Setzler were a brazen theft, and it is not really surprising that, when the stolen bones were buried on the edge of Gunbalanya in 2011, Wamud, conscious of the television camera, lectured severely in English to all assembled: ‘Stealing people’s bones for study is no bloody good.’ But to confine the transgression to the act of theft is to understate the gravity and complexity of the problem. Theft is a crime against property, whereas this was a crime against people. The removal of bones is closer to kidnap from this point of view. Taking the bones presented Bininj and Aboriginal people from other parts of Arnhem Land with the terrifying possibility that spirits had been wrenched from their country and taken abroad on what Wamud called a ‘long walkabout’. Now the Bininj must deal with the bewilderment and possible anger of the spirits upon their return to Australia.

It took twelve months for the Bininj to decide how to deal with the repatriated bones. During that period they were locked in a shed attached to premises occupied by Bill Ivory, Gunbalanya’s government business manager. In addition to the two repatriations from Washington, remains returned by other institutions, among them the Museum of Victoria, had been added to the pile of boxes. A few weeks earlier, Steve Webb, a physical anthropologist at Bond University, visited the town to sort the bones. The Bininj avoided handling or even looking at them for as long as possible. They seemed happy to delegate the technical work to Balanda, and Webb’s contribution signalled a significant transition in their recognition as human subjects. The bones had been stolen in the service of physical anthropology, so perhaps it was appropriate that the specialised knowledge of that discipline should be brought to the service of the bones themselves, now that their long walkabout was ending. At the request of Wamud and others, Webb was asked to identify the sex of the remains and, insofar as he could, to bundle together the bones of individual people. Wrapped in paper, no longer specimens but now individual men, women, or children, a coloured arrow pointed in the direction of the head (though in some cases the skull was missing). Webb then returned the bundles to their cardboard boxes. They were in this state on 19 July 2011 when, with a plentiful supply of paperbark sheets torn from trees the day before, preparations for burial began.

‘Theft is a crime against property, whereas this was a crime against people. The removal of bones is closer to kidnap’

Reuben Brown, a PhD student who is studying sound recordings made on the Arnhem Land Expedition, fetched Wamud from his house, pushing him through town in his wheelchair. Wamud’s son Alfred Nayinggul and other senior men and women were waiting, as were Suze and Adis with microphone and camera, and Glenn Campbell, a photographer representing the Fairfax media group, whose work that day would win him a Walkley Award. A fair amount of discussion had occurred about where the wrapping should take place. Assuming that privacy would be required for proceedings so sensitive, we had used sheets and tarps to screen off a section of enclosed verandah that was part of Bill’s living quarters. As with many things that were apparently pre-decided, Wamud reversed his position as events unfolded. The boxes, he declared, would be opened outside in the shelter of a carport. Nothing would be hidden.

The charred remnants of the cardboard coffins

The charred remnants of the cardboard coffins

Only the previous day I had asked Wamud what, if any, of the preparations could be photographed. He said that we should start filming just before the bones were about to be wrapped. Overnight, however, Wamud decided that the proceedings should be documented more thoroughly. I heard later that Glenn Campbell’s photographs in The Age, in which the bone handling was depicted in all its stark intimacy,were considered culturally inappropriate by gatekeepers in the metropole. In fact all of this was intentionally made open to the public gaze. A blue tarpaulin, laid down on the ground, formed the photographic backdrop. The large pieces of paperbark were brought forth and pulled apart into thinner layers, establishing the foundation for the work that followed.

When the shed was finally unlocked, we gazed at the stack of boxes. As documenter of the repatriation, I don’t know that I’d ever been much of an omniscient observer, but from this time I became ever more a participant in the proceedings. Alfred, Reuben, and I began to remove the boxes. As tends to happen in Bininj way, if you hang around long enough, you become part of the action – at least to some degree. We carried the boxes, although significantly, as Balanda, we did not handle the bones. I am sure Alfred would have preferred us to do so. He had said to Bill the previous week how nervous he was lest he should be asked to touch them; he was fearful of falling ill or being otherwise molested by the spirits. As Alfred dithered before a box of bones in the carport, Wamud barked at him from the security of his wheelchair and told him in effect to get his act together: to get those bones out of the boxes and prepare them for burial.

‘As tends to happen in the Bininj way, if you hang around long enough, you become part of the action – at least to some degree’

At a recent conference I showed some of this film. Of course I had to edit it severely, removing from sight the figure who was, and who in time again will be, centre stage. In the doctored footage, even without his visible presence, his power over the scene is palpable. Or perhaps it is made more obvious because of his invisibility. For what is a taboo if not a form of emphasis? In editing the sequence, Adis and I manipulated not only the visual but also the audible record, for Wamud’s chief role in these proceedings was not only to command the living as they went about their labour of tending to the dead – this he did with authoritarian severity – but to talk to the spirits, to calm them, assuage them, to tell them where they were.

I believe that the necessity of doing this had long preoccupied him, and it explains why he alone, among the few veteran old people of the community, was qualified to perform the role he did. Lorrkkon, the hollow log ceremony, is now defunct, but aspects of it survive, as is evident in the way the bones were ochred and wrapped. But most of all it was Wamud’s linguistic heritage that made him uniquely qualified to perform the work required on that day. Gagadju, Urningangk, Erre, and Mengerrdji were the languages native to Wamud’s ancestral estates around the East Alligator River, and the ones in his estimation likely to be most familiar to the spirits. Competency in those languages has fairly much died with him, although I suspect that even his was little more than a remnant knowledge. Kunwinjku, which arrived in Gunbalanya with migration from the east, has for the most part replaced these tongues, as has Kriol and, to some extent, English.

After the burial he did what he could to translate what it was he said to the spirits, but pain and failing strength prevented much progress. So I must add this failure to my unhappy list of uncompleted tasks. But the gist of it he paraphrased. As each box was opened, he began his incantations. He told the spirits his name. He told them of the major landmarks: Argaluk (towards which their head would lie) and Injalak (to which their feet would be pointed). He told them that they had come home and would be laid to rest, not in the caves from which they were stolen, but deep in the ground where no one could take them again.

The preparation of the bones lasted the greater part of the day, Wamud maintained his dialogue with the spirits. The men worked on men’s remains; women worked on women and children. Red ochre was ground and mixed with water, and not merely applied to the bones, but massaged into them. Wamud said to me, as he presided over this scene of industry, immeasurably satisfied, that they were ‘dressing’ them. Painted with the pigment of the earth, as in life they had been painted for dance, it was a final kindness from living hand. Fibulas and tibias were quickly coated with a hand plunged into the red solution, rich as blood. The smooth domes of crania were coated, quickly drying to a powdery rust; eye-sockets were daubed with dripping fingers. The discovery of a stray tooth had Donna Nadjammerek, one of the embalmers, testing socket after socket until at last she restored it to its owner.

The bundles of bones we had in a way been ready for, but the plastic bags defied all expectation. Inside them were the tailings from the archaeologist’s sieve: humanity reduced to splinters and fragments. Big bags bulged with larger pieces, like coarse gravel. Tiny bags, no bigger than drug deals, held quotas of grit. No hope of painting this stuff. After what seemed interminable emptying onto their cushiony layer of paperbark, they were quickly bundled and tied, and the bags, like all the boxes and wrappings tainted by their contact with the dead, were put aside to be taken to the grave site next day. Ashes to ashes. Dust to dust.

The ceremony that ended the long walkabout began with a procession through the town. To my great honour Wamud asked that I push him in his wheelchair. As we set off with Bill, Alfred, Donna, Wamud’s daughter Connie, politicians, dignitaries, and others, he barked at me constantly to walk slowly, more slowly, slower still. With singers and didgeridoo beside us, guiding the spirits in a current of song that would eventually coax them into the confined space of the grave, we maintained a funereal pace. The boxes of bones were following in a cortège of four-wheel drives. People watching from their houses fell in behind the vehicles as the march proceeded. All were invited: Bininj, Balanda, visiting workers, and tourists shopping at the art centre. At the grave site Wamud spoke at length, in various languages, to the assembled audience and the spirits. To the latter he explained that they had been divided into men and women, Bininj and Daluk, just the same as if they were camping.

The bundles were buried in deep trenches and filled with earth. As the crowd dispersed, and headed off for a barbecue laid on in celebration, the boxes and wrappings that had held the bones were torched. A flash of orange, and the cardboard coffins were no more. Their destruction, as much the burial itself, confirmed that the status of the bones as mere objects in a museum had irrevocably ended.

I was there a month later, without the film crew. It was the last time I saw Wamud, who was by then largely confined to the horrific squalor of his bed. I recorded an interview in which he said that he was immensely satisfied with the job we had done. By this he meant the film, of which I had shown him rushes, as well as the greater project of restoring the spirits to their country. I asked whether the film was intended as a guide to those who might be dealing with repatriations in the future. He said that was one of the reasons. But foremost, I think, was the desire to say something about his life and memories, and to perpetuate his lifelong interest, dating from his childhood on the mission, in communicating across cultures. Arnhem Land is rich in many things, poverty among them. He wanted to open something of his world to you and me.

He is buried now in his cherished homeland, Mikkinj Valley, south-east of Cahills Crossing. He often spoke of this place; had it been possible, he would have died there. When, in July 2012, they found room for him in the Gunbalanya morgue, he was brought back to town and laid to rest at last. There was the big church service in Gunbalanya. And then – to use your words, Wamud – they took you to Mikkinj because it’s your country.

Hundreds made the journey to camp with him as his body lay resting in a shelter made of boughs. They sang for him night and day, and each and every mourner, black and white, went to sit with him, and in their own way, in their own time, in their own language, each said goodbye. As they buried him, small whirlwinds were seen dancing through the campground and were immediately identified as his spirit.

At night, young men patrolled the border of the camp and periodically called out to him in Kunwinjku, telling him to go back. ‘Go back! Go back!’ they cried. ‘Go back!’ Why go back? Wasn’t he already back? All finished up and back in his country? Yes, indeed. But they meant back to the spirit world, back to the place from which he started, and to which, we might suppose, he has now returned. For the moment we must leave him, at home in his country, and avoid for a time the temptation to recall him. This beautiful country. Because it’s your country. Troubled and majestic, battered and beloved; this is his country, the greatest teacher of them all.

The Calibre Prize for an Outstanding Essay was first presented in 2007 and has become Australia’s premier essay prize. Originally sponsored by Copyright Agency (through its Cultural Fund), Calibre is now funded by Australian Book Review. Here we gratefully acknowledge the generous support of ABR Patron Mr Colin Golvan SC.

Remarkably, his winning entry, ‘Four Sonnets’, is his first new poem in a quarter of a century. Not that Mr Scott has been idle during this time. He is the author of sixteen books to date. His novel What I Have Written won a Victorian Premier’s Prize in 1994, and his novels Before I Wake (1996) and The Architect (2002) were shortlisted for several awards, including the Miles Franklin Award. He has a new book coming out this year with Brandl & Schlesinger, the experimental novel N.

Remarkably, his winning entry, ‘Four Sonnets’, is his first new poem in a quarter of a century. Not that Mr Scott has been idle during this time. He is the author of sixteen books to date. His novel What I Have Written won a Victorian Premier’s Prize in 1994, and his novels Before I Wake (1996) and The Architect (2002) were shortlisted for several awards, including the Miles Franklin Award. He has a new book coming out this year with Brandl & Schlesinger, the experimental novel N. well. Meanwhile, we hope to announce details of a fourth paid editorial internship in coming months.

well. Meanwhile, we hope to announce details of a fourth paid editorial internship in coming months.