- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

However much we may locate the joy of travel in the sudden revelations of a new experience, one of its most enduring pleasures lies in collecting for later. For the collector–traveller, journeys abroad offer an escape from the familiar and, as importantly, a chance to assemble a different kind of education from the one we receive at home, a living textbook shaped by first-hand encounters and the possibility and urgency of adventure.

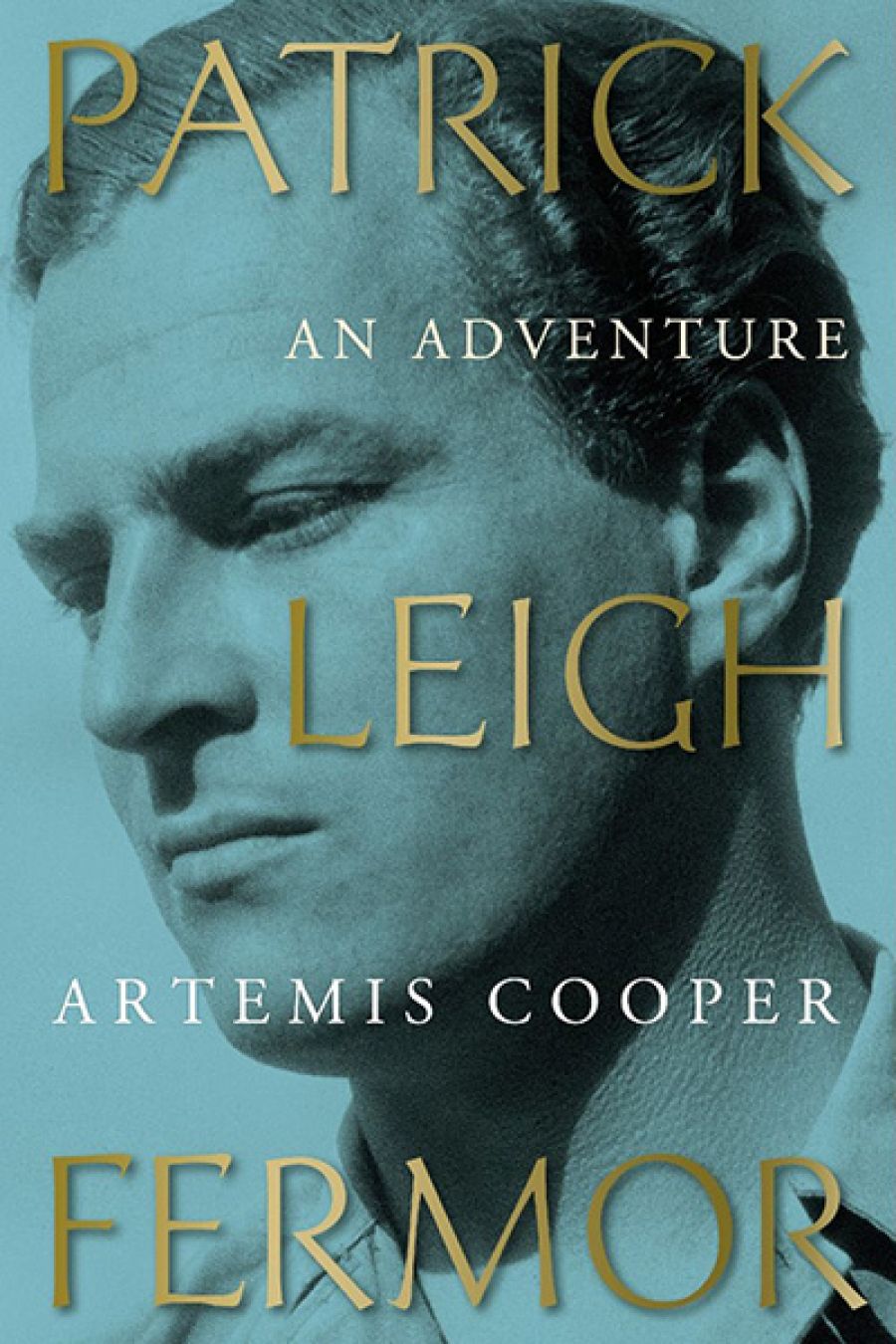

- Book 1 Title: Patrick Leigh Fermor: An Adventure

- Book 1 Biblio: John Murray (Hachette Australia), $49.99 hb, 464 pp, 9780719554490

There is no doubt that Patrick Leigh Fermor (1915–2011) made the most of a crowded life of travel and a dazzling collection of friends and chance encounters. He combined reading, writing, and constant engagement with the world in a way that expressed how a man of action could also see himself as a servant of language. Early in his writing life, he retreated to monasteries in order to find respite from the excesses of his social life, but, as with warrior–poets of earlier times, the call of language was never altogether separable from the call to adventure. This was a writer who needed to be in the world in order to find a reason to retreat from it.

The digestive task for Artemis Cooper, a biographer whom Fermor knew well, began with the untangling of legend from a rich body of work that in the postwar years came to form part of not only the English canon of travel writing but also the English imagining of World War II. Europe before the war had consisted of many wonders, which Cooper gathers around Fermor’s famous walk from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople, commenced in December 1933 and later written up in two volumes of travel memoir, A Time of Gifts (1977) and Between the Woods and the Water (1985). We witness codes of hospitality preserved since the Middle Ages; a common conception of classical education evidenced by one private library after another; belief in the infinite possibilities of the young mind, no matter how scraggy or indeed handsome its possessor; and commitment to charm and conversation as markers of civilisation, not merely civility. Adding poignancy to these travels is the fact that the brightness of these jewels was already being dulled by Hitler’s ascendancy and the sense of what it might bring for many of the people whom Fermor meets.

Most important among these is the Romanian Princess Balasha Cantacuzène, who offered the wanderer not only hospitality and love but also a chance to escape the influence of his rather difficult mother and to finally realise the ‘bookish attempt to coerce life into a closer resemblance to literature’. In Balasha, Fermor discovered a profound engagement with the ancient lineages of Europe. They had long captured his imagination, but now there was an emotional history at the base of his many other encounters with the aristocracy – not least the female aristocracy – and the communities that were to be found near the castles and mansions. Fermor, often praised for his egalitarianism, valorised folk traditions as well as those of the gentry, particularly in his writing about Greece. And if there were some purchase to Somerset Maugham’s description of him as a ‘middle-class gigolo for upper-class women’, his life as we find it in this study is more meaningfully cast in terms of two enduring if unconventional relationships, one with Balasha, which lasted until the beginning of the war, and the other with photographer Joan Rayner, whom he met at its close.

Fermor and Joan began a partnership that gave Fermor financial support and the emotional stability that had been missing during his childhood. It also came with freedoms for which that childhood had prepared him. They ‘agreed that their relationship would never be fettered by possessiveness’, a philosophy that over the years benefited Fermor much more than it did his life companion, and that inevitably reached its limit. Joan eventually told Fermor that she would no longer sleep with him, but at the same time continued to help fund their life together and even his ‘weakness for the sleazier pleasures of the night’.

Cooper makes no apology for this weakness; nor does she indulge in anything like pity for Joan. The approach, instead, is to document this aspect of Fermor’s treatment of others in the same objective voice that is used to describe more glamorous events and for those parts of the adventure that enabled Fermor to seduce not only rich women but the English public as a whole.

Chief among these events, and ‘the one he was most fond of recalling in interviews’, forms the centre of the biography. In April 1944, Fermor led an audacious mission to kidnap the German commander in Crete, General Heinrich Kreipe. During the kidnappers’ escape from the island, the general began to recite poetry. Recognising one of Horace’s Odes, Fermor completed the lines. There was an immediate understanding between captor and prisoner, framed by codes of honour and hospitality that Fermor had cherished during his walk across Europe.

One wonders whether this moment might not also have helped the general to understand why on earth he was being kidnapped. When he asked Fermor for the object of the mission, ‘Paddy had to admit that there was no easy answer to that question’. But perhaps, after all, the answer lay in literature, or in that process of bringing life to more closely resemble it. The hero must heed the call of adventure and travel to distant lands, and, if it does not altogether meet the demands of the war effort for the hero to be undertaking daring feats, it most certainly meets the demands of the genre. That there would be reprisals for those who remained behind was of course as much a part of British operations in Crete as it had been for earlier adventures.

There will always be the matter of Grendel’s mother. In Crete she arrived in the form of German attacks on villages, and, in Fermor’s life more generally, in the form of the damage often visited on the friends of those who embrace a fast life. Cooper notes that Fermor disliked analogies between him and Byron, but they remind the reader that heroes sometimes prefer to concentrate on the first parts of their stories: the setting out and the conquest. Fermor did not like the idea of a biography, and Cooper’s work helps us to see why. While her analysis is rather light, she documents criticisms when required, including those of the British efforts in Crete and the repercussions of those efforts for the local people. There is enough in this work to suggest that Joan’s side of the adventure was probably the more demanding. Yet Cooper also demonstrates in the same even tone that Fermor’s commitment to both Greece and Joan was lifelong and genuine. In the Greek seaside town of Kardamyli, the couple built a house where they could reflect on their remarkable travels, in what John Betjeman described as ‘one of the rooms in the world’. This great adventurer had, after all, charmed his way into many.

Comments powered by CComment