- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In one of Georgia Blain’s subtle, beautifully paced stories, a young girl is given an IQ test. Believing it to be a game, she is outraged when her older brother crows about his results and she realises she has been evaluated. Later, as an adult, she can put her childhood indignation into words: ‘I thought it was just a matter of random chance. I should have been told that there was a predetermined pattern for me to decipher, and rules to follow.’ But at eight she can only protest at the psychologist’s betrayal: ‘She never said it was a test.’

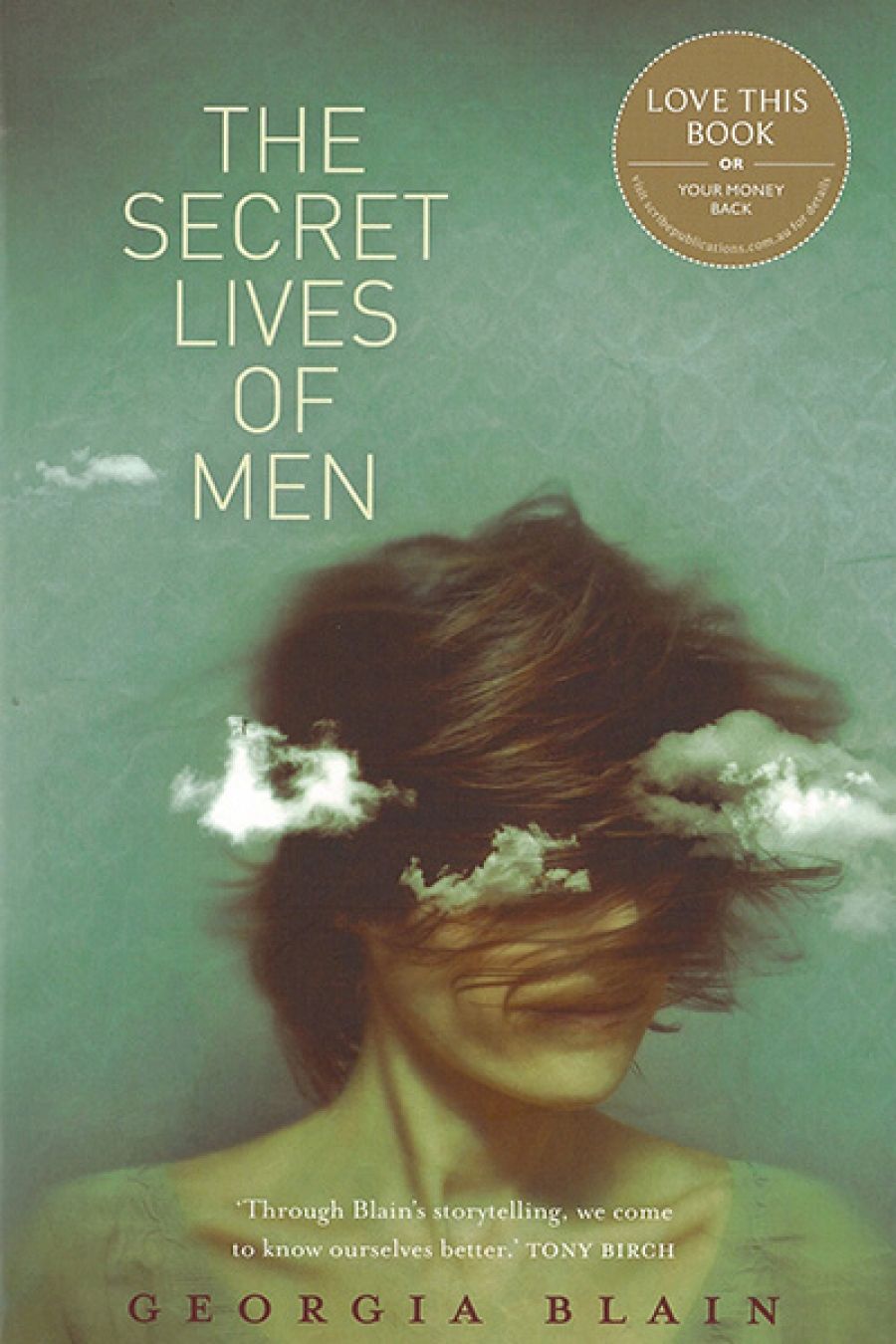

- Book 1 Title: The Secret Lives of Men

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $27.95 pb, 256 pp, 9781922070357

Throughout The Secret Lives of Men, we meet characters confronting a similar realisation – that the choices they have been making or avoiding, often with thoughtless repetition, have counted. Some respond with rising panic, others with resignation. Occasionally, as in the final story, they make a kind of peace with their past decisions, missteps and all. The cumulative effect is complex and moving; Blain is at once unflinching and compassionate in her portrayal of mid-life inertia and remorse.

With a few exceptions, men are on the fringes of these stories, their inner lives concealed. Most of Blain’s narrators are intelligent, likeable, self-critical women, but their self-criticism does not always lead to self-awareness. Bored, lonely, or anxious, they feel compelled to take decisive, uncharacteristically feckless action; we often see them either poised to act rashly or dealing with the repercussions of having done so.

Such a pat summing-up is, of course, too simplistic, and Blain herself is never so heavy-handed. Her prose, precise and controlled, often evokes emotional intimacy and ironic distance in a single carefully turned sentence. In ‘Just a Wedding’, a young woman on her honeymoon wakes hungover in a Spanish hotel. Her half-awake senses pick out just the details we need to know her state of mind.

Next to her, Charles was still asleep, his eyelids waxy, his mouth slightly open … She could smell sangria, like rotten fruit, overripe in the room … a fly buzzed, and then settled on his shoulder. She shifted away from him carefully, not wanting to wake him, because then she could no longer be alone.

Many of these characters tread a dangerous line between self-effacement and self-loathing, and let bad things happen to themselves as a result. They walk knowingly into unhappy love affairs, or are silent when they know they should speak, almost as though inviting trouble.

Others assume that recklessness is symptomatic of love or courage, a mistake they often come to regret. When a brash young man makes a case for hasty courtship, there is a glib truth in what he says, and it is tempting to believe him: ‘You don’t want to wait until you know each other. Who’d get married then?’ But these stories are full of women who mistake carelessness for passionate abandon, or who try to. The young man’s bride knows that she has not really been swept up in an irresistible romance, even as she wills herself to believe it. She suffers from a ‘strange inclination to try on the clothes of another woman, someone more colourful than she had ever been’. Once the clothes were on and the initial thrill past, ‘she felt like a silly child again, this time in an outfit that was too large, and – quite frankly – embarrassing in its glary flamboyance’.

In ‘Big Dreams’, a lonely woman toys with telephoning an utterly unappealing man. ‘She puts her wineglass down and finds herself giggling … Without thinking, she begins to dial the numbers, one after the other, wanting only to act in a way that is completely unexpected.’ The feeling of freedom in these cavalier moments is short-lived and deceptive. The out-of-character deed done, she finds that she is still her awkward self: ‘She hovers, caught in a space that cannot last, mouth open ready to speak, hand poised, ready to hang up, floundering as he asks her who’s calling and she stumbles to say her name.’

Despite these recurring scenarios, there is none of the monotony that sometimes spoils short story collections, and the narrators are not all of a type. In ‘Escape’, a twelve-year-old boy, bored on summer vacation, is thrilled to learn that an armed robber is at large and to find himself on the sidelines of the action. His naïve narration, his nervous curiosity about strange adult behaviour, set the story up as a kind of ironical boy’s own adventure, gently satirical: ‘The excitement at speaking to a real criminal [was] almost too much for me. He could trust me, I added, if he had any message he wanted to pass on … I took down the details, repeating them to him as my mother had taught me, only to find that he had hung up before I got to the end.’ But behind this comically earnest child’s-eye view is something deeper, and Blain shows exquisite restraint in letting it peek through. She respects the limits of her narrator’s voice and understanding, but uses the boy’s own faltering observations to take the story somewhere unexpected and disarming.

This is a finely tuned collection, thoughtfully written and arranged, with profound and unsettling things to say about love, loneliness, and risk. It explores without condoning the compulsion to act for action’s sake. As one character puts it: ‘When total destruction knocks on your door, sometimes it’s very tempting to take a look.’

Comments powered by CComment