- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Arthur Augustus Calwell is hardly the most celebrated or mythologised politician in the history of the Australian Labor Party. His achievements as the first minister for immigration have been overshadowed by his very public advocacy of the White Australia policy ...

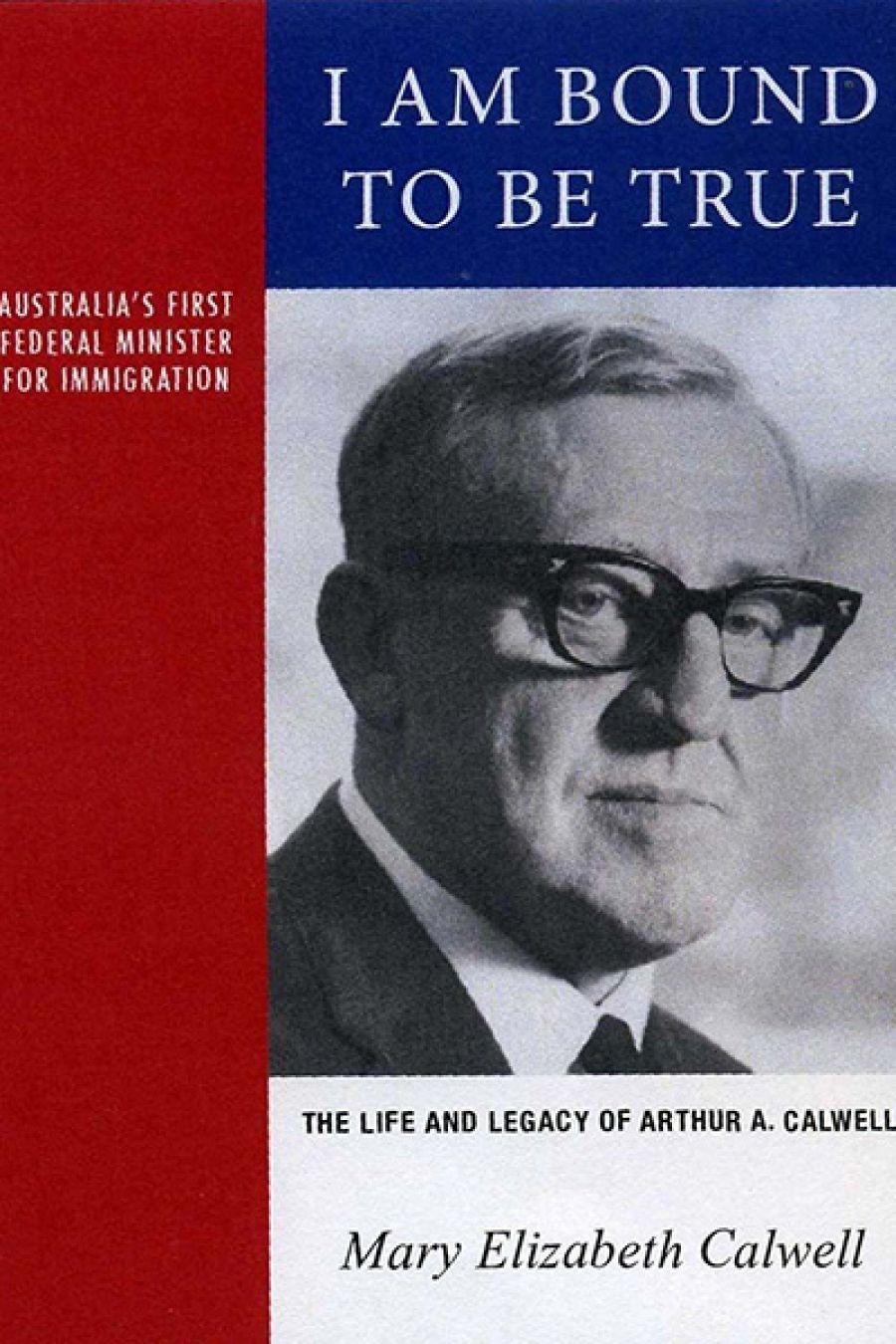

- Book 1 Title: I Am Bound to be True

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Life and Legacy of Arthur A. Calwell, 1896–1973

- Book 1 Biblio: Mosaic Press, $39.95 pb, 260 pp, 9781743241400

There are two probable reasons for Calwell’s failure to achieve greater recognition. First, Calwell was Opposition leader (1960–67) at a time when infighting and disunity within the ALP often attracted more media attention than its policy direction. Secondly, Calwell’s White Australia sentiments made him appear old-fashioned by 1972, when he insisted that ‘No red-blooded Australian wants to see a chocolate-coloured Australia in the 1980s’. His racial attitudes were more complex and broad-minded than this, but such outbursts helped to create the impression of a man on the wrong side of history.

Not wanting to be remembered as a footnote in Labor history, Calwell himself wrote an entertaining and informative memoir of his life in politics (Be Just and Fear Not, 1972). This was followed in 1978 by historian Colm Kiernan’s sympathetic but not uncritical biographical study. With the benefit of hindsight, the theme that comes through these early publications is that Calwell was the last of the old-style Labor leaders, representing a traditional working class whose identity by the 1960s was becoming fragmented. The Irish Catholic vote could no longer be taken for granted, and class divisions were blurring as increased education and prosperity helped develop a greater number of young, upwardly mobile professionals to whom Calwell was less appealing than was Gough Whitlam.

In recent years, historians such as Gwenda Tavan and Sean Brawley have closely explored aspects of Calwell’s period as immigration minister (1945–49). Now, after several decades, a new biographical portrait of Calwell has been published. The late politician’s daughter, Mary Elizabeth Calwell, has produced an affectionate and at times moving account of her father’s life and times. She emphasises Calwell’s lifelong attachment to his church and his party.

The author takes a largely chronological approach to the Calwell life story, which centres on his home town of Melbourne. Although his father was a Protestant, Calwell was brought up in his mother’s Catholic faith and identified strongly with his Irish Catholic heritage. Like many bright, ambitious Catholics of his era, after finishing school he entered the state public service, which, for many years, provided him with an income while he built up his profile within the Victorian branch of the ALP.

His political rise was slow but sure. By 1926 he had decided that he wished to become the federal Labor member for the seat of Melbourne after the sitting member, Dr William Maloney, had retired. Unwilling to challenge Maloney for preselection or try for another seat, Calwell helped Maloney (aka the ‘Little Doctor’) with his electoral duties. Only when Maloney died in 1940 aged eighty-five was the younger man able to succeed him. As an ALP flyer reproduced in Mary Calwell’s set of illustrations indicates, this unabashed loyalty and service was used as a selling point in Arthur’s 1940 election campaign: ‘“Little Doc.” Still Lives: Successor was Man he Selected.’

Calwell was MP for Melbourne from 1940 to 1972. He subsequently became a minister in the Curtin and Chifley Labor governments (1941–49). Motivated partly by fears of invasion and the potential decline of White Australia, Calwell was an energetic and effective immigration minister. Whatever his motivations, his promotional and administrative skills were crucial to the acceptance of an unprecedented level of European migration from countries beyond the British Isles. The work of Calwell and numerous officials helped many families from war-torn Europe to build new lives in Australia and to make great contributions to the economic and social life of this country.

While Calwell encouraged Australians to accept ‘New Australians’ from unfamiliar nationalities and cultures, he remained a determined defender of the White Australia policy. Calwell’s pugnacious insistence on deporting Asian refugees who had arrived in Australia during World War II made him a highly controversial figure both in Australia and overseas. One of the criticisms I would make of this biography is that the more contentious aspects of her father’s career, such as immigration, are not analysed or considered with sufficient depth. The author is at times overly reliant on highlighting her father’s own response to criticism of his work as immigration minister, and leaves some issues unresolved.

More positively, the author counterbalances the public image of Calwell as an uncompromising White Australia advocate with his more generous and kind persona beyond the media gaze: his empathy and support for Chinese Australians were especially notable. Calwell does not seem to have had much trouble relating personally to Asians or other racial groups. However, his fear of interracial divisions and strife governed his belief in a (mostly) racially exclusive society, a view which was shared by many people of his generation.

The author also emphasises Calwell’s passionate belief in separation of church and state, which seemed under threat in the 1950s because of Catholic activist Bob Santamaria’s attempts to influence the agenda of the ALP. The outcome of this sectarian tension was the Labor split, and the formation of the Catholic-dominated Democratic Labor Party. Calwell was hurt personally and politically by these developments. Remaining loyal to the ALP, he was subject to abuse and condemnation by elements of his church, who, to paraphrase a contemporary Labor MP, were praying for him but not voting for him. The author also shows the extent to which Calwell turned to church literature to help him articulate his belief in church–state separation, both to himself and to others.

As the daughter of Arthur Calwell, Mary Calwell is too close to her biographical subject to be objective. Some material will be of more interest to family and friends than to the general public, and much historical knowledge is assumed rather than explained to the uninitiated. However, the author’s work serves to remind the reader of the importance of Calwell as a public figure, and shows how political ambition and achievements, both then and now, can often come at an immense personal cost.

Comments powered by CComment