- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Advances

- Review Article: No

- Article Title: Advances – August 2024

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

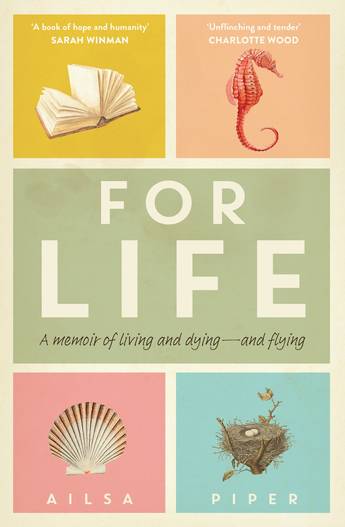

The Jolley Prize

This year’s ABR Elizabeth Jolley Short Story Prize attracted 1,310 entries. Of these, 413 came from overseas, attesting to the high regard in which the Jolley Prize – one of the world’s most lucrative prizes for an unpublished story in English –is held internationally.

Our three judges – Patrick Flanery (Adelaide), Melinda Harvey (Melbourne), and Susan Midalia (Perth) – longlisted thirteen stories from twelve different writers (John Kinsella doubled up). These are all listed on our website, and we congratulate the longlisted authors.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Advances – August 2024

The Jolley Prize

This year’s ABR Elizabeth Jolley Short Story Prize attracted 1,310 entries. Of these, 413 came from overseas, attesting to the high regard in which the Jolley Prize – one of the world’s most lucrative prizes for an unpublished story in English –is held internationally.

Our three judges – Patrick Flanery (Adelaide), Melinda Harvey (Melbourne), and Susan Midalia (Perth) – longlisted thirteen stories from twelve different writers (John Kinsella doubled up). These are all listed on our website, and we congratulate the longlisted authors.

The judges have now shortlisted three stories, and it’s our great pleasure to publish them in this issue:

‘First Snow’ by Kerry Greer (WA)

‘M.’ by Shelley Stenhouse (USA)

‘Pornwald’ by Jill Van Epps (USA)

In their report, the judges had this to say about the wider field:

We were pleased to encounter a range of forms and genres, from literary realism to satire, speculative and historical fiction, dystopia, autofiction, and more experimental work. The stories explored themes of love, sex, and the pain of being alive, while many took an overtly political stance, addressing anxieties about climate change, social justice, and the rise of Artificial Intelligence.

The judges gravitated towards stories marked by an inventiveness of form and a distinctiveness of voice, stories that had something surprising to tell us and found imaginative ways of expressing ideas. The shortlisted stories negotiate the challenges of the form by skilfully combining brevity and depth, economy and resonance, offering refreshing perspectives on the world.

The judges’ full report, which can be found online, contains remarks on the three shortlisted stories.

The Jolley Prize is worth a total of $12,500, and here, as ever, we thank Ian Dickson AM, who has generously supported this prize since its creation in 2011.

Now to find out who has won the overall prize and thus receives the first prize of $6,000. We don’t have long to wait. Join us at Gleebooks in Sydney on Thursday, 15 August (6 pm), when we will introduce the winner.

It’s been a while since we hosted a big event in Sydney, so this will also be an opportunity to thank our countless writers and supporters in New South Wales.

It’s essential to RSVP via Gleebooks’s event page on their website.

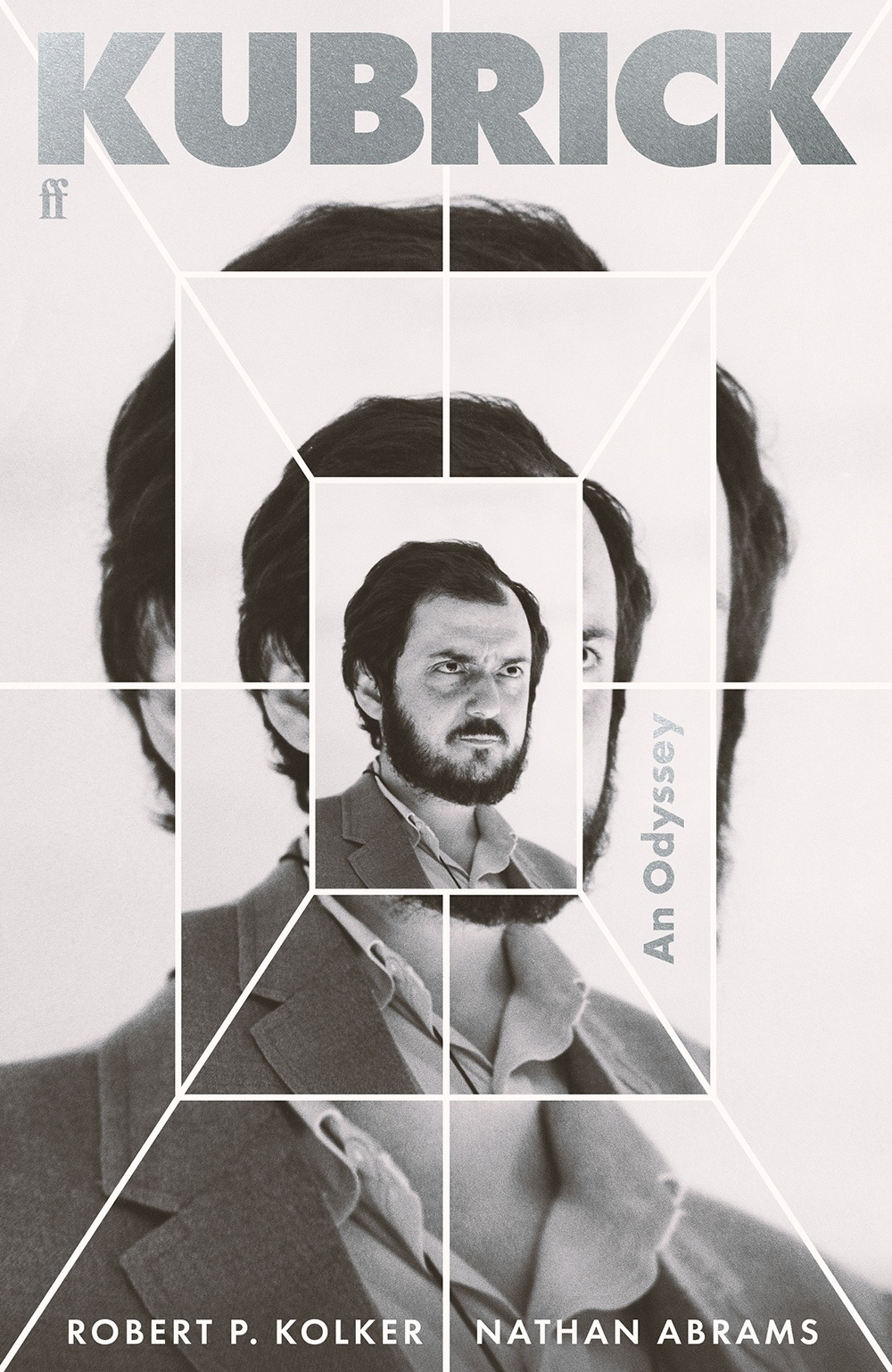

On the roof with James Baldwin

‘Inimitable’ is a trite word – a hairdresser’s word, as Pasternak said of ‘genius’ – but it seems uniquely applicable to James Baldwin – novelist, essayist, activist, incendiary polemicist – who died far too young, in 1987. The centenary of Baldwin’s birth falls on 2 August. To commemorate it, and to explore his matchless and fluctuating influence, Paul Kane writes about Baldwin’s life and work in this month’s cover feature.

This enables us to reproduce Juno Gemes’s portrait of Baldwin, which was taken (at Baldwin’s suggestion) on the roof of the Athenaeum Hotel, London in 1976. Juno, in 2020, wrote about that hour-long photographic session for the Rochford Street Review (still available online). ‘With respect and warmth, I said to [Baldwin] cheekily, “You are the prince of all your survey.” He looked out across the roof parapet. He smiled wryly … In that moment I had my portrait.’

In December, Upswell will publish Juno Gemes’s magnum opus: Until Justice Comes: Fifty years of the movement for Indigenous rights: Photographs 1970-2024.

On the verge

Advances always looks forward to the new iteration of Verge, the annual creative writing anthology from Monash University Publishing. This year’s edition is crisply titled Click. The editors – J. Taylor Bell, Julia Faragher, Isabella G. Mead, and Anna Pane – have included twenty-six writers from Monash University and beyond. Among them are Kayla Willson, Dominic Symes, and ABR’s very own Will Hunt, who has a work of autofiction – his first creative publication. Congratulations to all.

David Marr and LNL

After Phillip Adams’s epic reign at Late Night Live, everyone was looking forward to David Marr’s commencement in mid-July as the new host of this essential late-night radio program. Early on, he spoke at length to military historian Joan Beaumont – a fascinating elaboration of the ideas advanced in her article on Ambon and postmemory in our July issue.

Look out – or listen up – for Paul Kane’s appearance on the program, apropos of James Baldwin. Paul also features on the ABR Podcast this month.

.png)