- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The biggest invisible thing

- Article Subtitle: Building on a trove of unknown history

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Increasingly, public understanding of issues vital to humanity’s well-being and future – climate change, health policy, international relations – is informed by debate that pits specious prejudice, masquerading as opinion, against expertise. Communicating with a lay audience, experts on complex yet politically charged subjects confront twin challenges: they must present evidence that is multifaceted and can provide no perfect or certain solution, while simultaneously dismantling arguments, founded in denialism, that endorse simple strategies and offer comforting but false hope. Experts and those who wish to construct evidence-based policy are struggling to meet these challenges.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Zoë Laidlaw reviews ‘The Truth About Empire: Real histories of British colonialism’ edited by Alan Lester

- Book 1 Title: The Truth About Empire

- Book 1 Subtitle: Real histories of British colonialism

- Book 1 Biblio: Hurst, £25 hb, 304 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

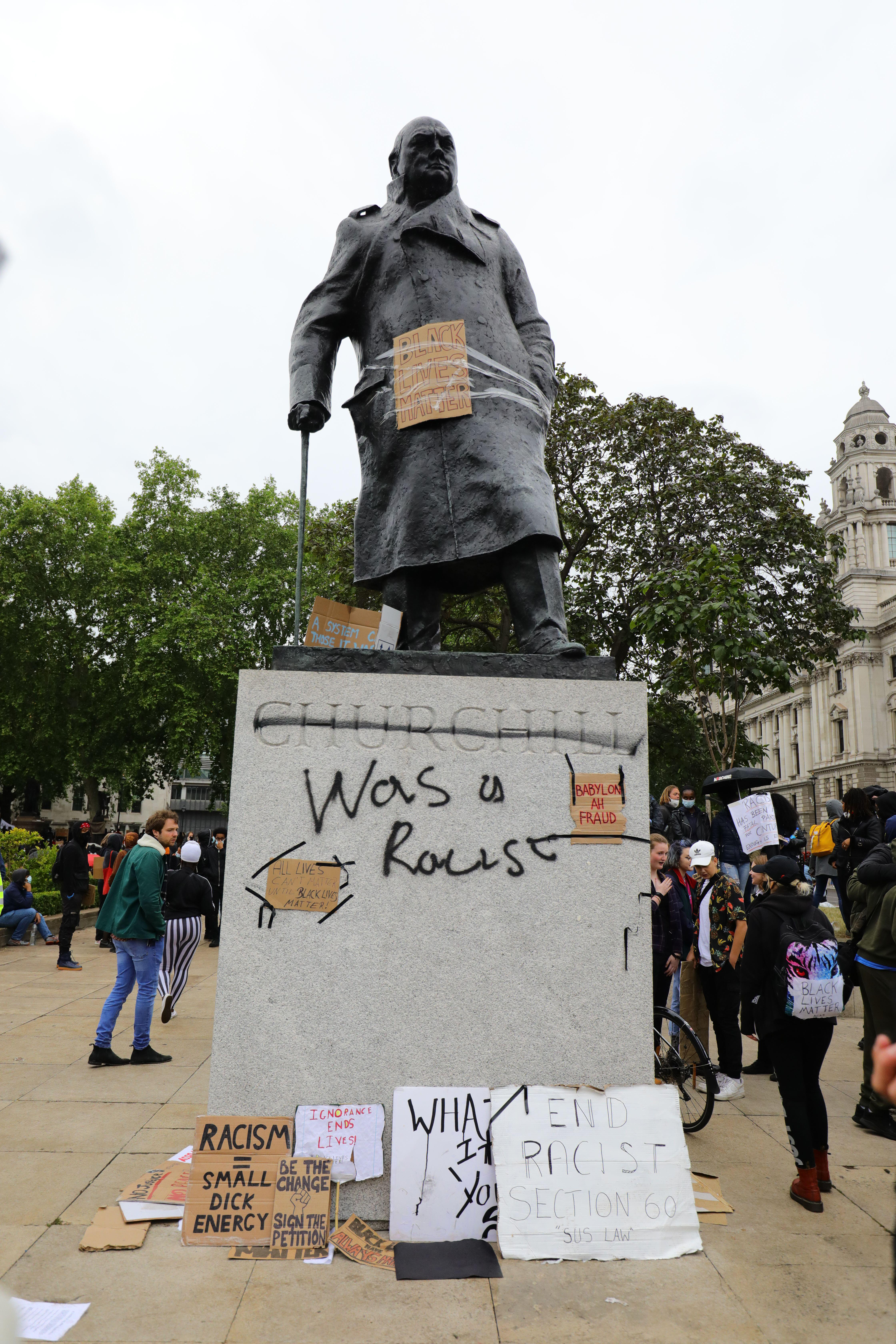

If with less apparent jeopardy, these dilemmas also confront historians. Although Australia’s ‘history wars’ of the early 2000s are now a historical episode to be picked over by academics and casually invoked by the media, the national past remains a publicly contested site. We continue, as a nation, to debate the present via the past, as was especially evident during the 2023 referendum campaign. In this, Australia is not alone. In 2020, British Black Lives Matter protesters toppled a statue of slave trader Edward Colston into Bristol Harbour and daubed ‘was a racist’ on Winston Churchill’s Westminster statue. Scholars researching the history and legacies of Britain’s empire are subject to vituperative attacks, especially if they are non-white or female. A 2019 report on colonial links to stately homes across the United Kingdom provoked a barrage of abuse for its author, Professor Corinne Fowler, and an attempted coup at the National Trust’s 2022 council elections. British Nigerian David Olusoga, a high-pro-file historian of Black Britain, has to employ a bodyguard at public events. Arguments ostensibly concerned with long-lost imperial power and its consequences are actually contests over the very nature of the not-so-United Kingdom and its less than glorious post-Brexit present.

Leading the rhetorical charge against both the statue-topplers and the historians of empire is a group calling itself ‘History Reclaimed’. It decries presentations of Britain’s past as ‘overwhelmingly and permanently shameful and guilt-laden’, hosts a slick website, and writes opinion pieces for Britain’s conservative press. Several members are historians, although their areas of expertise are not British colonialism. Their champion, Nigel Biggar, studied history long ago but made his career as an academic theologian before retiring in 2022. Last year, Biggar published Colonialism: A moral, which sought to present ‘a more historically accurate, fairer, more positive story’ about the British Empire.

As this suggests, those who promote a more positive reading of British imperialism make claims about the practice of history. Scholars whose work exposes the crimes, violence and graft associated with empire are charged not only with exaggerating, confecting, or wilfully misinterpreting the past but also with doing so to pursue contemporary ends, which might be characterised as ‘woke’. A new collection, The Truth About Empire: Real histories of British Colonialism, edited by Alan Lester, Professor of Historical Geography at the University of Sussex (with whom I have collaborated), robustly counters this charge. Lester, who critically reviewed Biggar’s Colonialism for the field-leading Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, now brings together sixteen experts on Britain’s empire to expose distortions of history and, crucially, to place History Reclaimed in its own historical context.

Grafitti on the Winston Churchill statue, photograph by Aaron Chown (PA Images / Alamy)

Grafitti on the Winston Churchill statue, photograph by Aaron Chown (PA Images / Alamy)

In a dozen pithy chapters, The Truth About Empire systematically reveals the questionable foundations of apologies for British colonialism. Each essay demonstrates how an aspect of Britain’s complex imperial past is understood by an academic expert. The arguments are compelling, the evidence transparent. Some respond directly to Biggar. Margot Finn’s final chapter is forensic in cataloguing the failures of Biggar’s historical method: his selective and skewed quotations and citations; his ignorance of ‘large and distinctive swathes of the historiographical landscape’; and his measurable bias against women and non-white people, whether historians or historical figures. Chapter after chapter – on Canada, China, India, South Africa, Singapore – reveals Biggar’s over-reliance on a small range of secondary works, his ignorance of crucial historical context, and his systemic bias against the perspective of the colonised in favour of the colonisers.

Few historians of empire will quibble with the book’s conclusions. It provides accessible, rigorously researched and clearly argued discussions of aspects of colonialism, including the end of empire, the opium wars, and why Britain opposed the slave trade. But it is unlikely to give pause to History Reclaimed or Biggar’s defenders: they are interested not in the ‘facts’ or ‘real histories’ of empire, but rather in a romanticised imperial past that serves a set of contemporary political myths.

Where The Truth About Empire will prove important is for those interested in the wider problem of the ideologically driven denial of expertise. It provides a meticulous historical examination of how and why questions about the morality of empire and responsibility for its consequences have proved such a political flashpoint in Britain. This scrutiny begins with a chapter on Tasmania by the late Lyndall Ryan. Ryan returns to the ‘history wars’, and one of the central provocateurs, Keith Windschuttle. In a self-published volume, Windschuttle sought to deny the scale of colonialism’s impact on Tasmania’s First Nations. In so doing, he used out-of-date population statistics, made unfounded claims about Tasmanian Aboriginal society, disputed contemporary accounts of massacres, and created a series of straw men by misrepresenting the arguments of scholars like Henry Reynolds and Ryan herself. Ryan shows how Biggar’s discussion of Tasmania ‘appears to take an even-handed approach’, but on each point privileges the long-discredited arguments of Windschuttle. Notably, Robert Manne’s collection Whitewash: On Keith Windschuttle’s fabrication of Aboriginal history (2003) foreshadowed what Lester seeks to do in The Truth About Empire, by bringing together expert historians to counter Windschuttle’s denial.

The Truth About Empire shows that an explicit but misleading emphasis on even-handedness has been a hallmark of British defence of empire for decades. There is, indeed, nothing new in seeking to present a positive view of Britain’s imperial record, nor in deploying an inherently flawed cost-benefit analysis to do so. Liam Liburd examines how interwar Black writers recognised the entanglements between fascism and imperialism. Yet to compare the two today is to provoke ‘hysterical opposition’. Erik Linstrum documents how swiftly Britons shed responsibility and evaded accountability for both empire and the violence of decolonisation. As Stuart Ward puts it, the genre of ‘empire retrospective’ is characterised by ‘the outward show of wrestling with the moral implications, while working subtly to wrest them from a weary conscience’. It is, it turns out, only ever apologists for empire who seek to deploy the colonial balance sheet.

To write about the past is not necessarily to write ‘history’. As a historical intervention, Biggar’s Colonialism does not deserve attention from academics. The Truth About Empire is both a masterclass in historical scholarship about facets of Britain’s empire ranging from slavery and statues to China and the South African War, and a reminder that history is about evidence and its provenance, that it involves rigorous and replicable analysis, and that the most robust findings are also nuanced. It will give ammunition to those who, like Richard Huzzey in his chapter on the abolition of slavery, question the idea that historical truth should be ‘subservient to patriotism’.

Comments powered by CComment