- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: Beyond the mundane: Popular science writing in our literary landscape

- Review Article: No

- Article Title: Beyond the mundane

- Article Subtitle: Popular science writing in our literary landscape

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

After Netflix’s intriguing sci-fi thriller 3 Body Problem streamed into Australia earlier this year, readers rushed out in droves to buy the book on which the series is based: Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem (2008), which was first translated into English in 2014. Most reviews have focused on the philosophical, literary, and cultural aspects of the book – and they are, indeed, fascinating. But the thing that interests me here is the accurate scientific detail that Liu uses to drive the story. Of course, this is sci-fi, so ultimately he presses real concepts into unreal (but imaginative) service. Still, much more physics and maths appear in his book than in the Netflix series, which, according to Tara Kenny’s review in The Monthly (April 2024), ‘offers a welcome workaround’ the science through visual effects. In the book, by contrast, ‘Lengthy passages are spent dutifully explaining physics theories and technological functionality, which is likely to deter readers who haven’t thought about science since they dissected a rat in high-school biology.’

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

.png)

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): ‘Beyond the mundane: Popular science writing in our literary landscape’ by Robyn Arianrhod

For Liu, science fiction ‘is a literature that belongs to all humanity’, and for me this is even truer of popular science. The best popular science writing offers readers a deeper appreciation of the sublimity of the natural world – and of the human intellect, which has unveiled so many of nature’s mysteries, like a marvellous magic mirror. Such writing also engages readers in the long view of our forerunners’ painstaking quest to understand the universe we all share – a quest whose imperative stems from our species’ insatiable curiosity, our yearning to know ‘why’; an odyssey whose history offers insight into the nature and conceptual development of science as it happened, wrong turns and all. And finally, the best science writing today acknowledges the multicultural foundations of modern science, and the significance of First Nations knowledge and of women’s contributions, which were marginalised for so long.

The best literary fiction writers also aim to capture something relatable and universal in the diverse specificity of human experience. As the Norwegian novelist Karl Ove Knausgaard wrote in The New Yorker (6 November 2019), ‘Science and literature alike are readers of the world.’ Yet literary popular science writing does not seem to figure in our literary canon, the books we set as recommended texts in English classes or recognise in our literary festivals and awards.

It hardly rates in our world-first national literary database, AustLit, either. This is no doubt due largely to AustLit’s small team and to our relatively small number of literary science writers, but still, we have more science writing than the current database suggests.

It is partly a matter of perception, and indeed, in her recent ABR essay (May 2024) AustLit director Maggie Nolan noted, ‘The definitions of both Australian and literature shift over time.’ She also hoped that the database would help us ‘to ask new kinds of questions about the Australian literary field’. This is an excellent goal, and an invitation, too, which I have taken up here as I offer some thoughts on why we should include our literary science writing – including literary writing that explains core scientific ideas – in our notion of Australian literature.

Of course, we live in a market-driven economy, so that if easier books are bestsellers, ever more of them are published. But a country’s canonical literature – or the literature recognised as the country’s best at a given time – encourages readers (and writers) to extend themselves in a deeper engagement with their place in the world. We often think of literary fiction in this light, but non-fiction also plays its part. Science, in particular, can take us beyond the mundane as well as any fiction. It allows us to marvel at the near-miraculous chance of our own existence, and glimpse our fragile, awesome place in the universe itself. And it allows us to see ourselves as part of the delicate web of life, as First Nations naturalists have done for thousands of years.

In his New Yorker piece, Knausgaard went on to say, ‘And, sooner or later, both [science and literature] lead us to the unreadable, the boundary at which the unintelligible begins’ – what Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell described as the boundary where ‘thought weds fact’. But here physical science has the edge. This is because its laws are written in a unique language, an elegant, universal language that is sometimes astonishingly prescient. For example, in their modern vector form Maxwell’s equations of electromagnetism (1864) look like a four-line poem, the patterns and repetitions of their symbols – intertwined like the physical electric and magnetic fields they represent – expressing a kind of visual assonance; but the truly remarkable thing about these equations, which Maxwell built from the observed physical behaviour of these fields, is that their poetic, mathematical structure also revealed to him things about electromagnetism that were not known at the time: the electromagnetic nature of light, and the likely existence of radio waves.

Maxwell’s prophetic equations, and their significance for our wireless, electric age, is one of the many thrilling scientific stories that literary popular science writers aim to retell in more accessible language. This is a challenging creative task, just as the best novelists must work hard to find the right language to illuminate aspects of everyday life in new ways. Maxwell himself was a brilliant popular science writer: a wonderfully lucid expositor and a wickedly witty popular writer whose speeches and articles ranged over vast scientific, literary, and philosophical terrain.

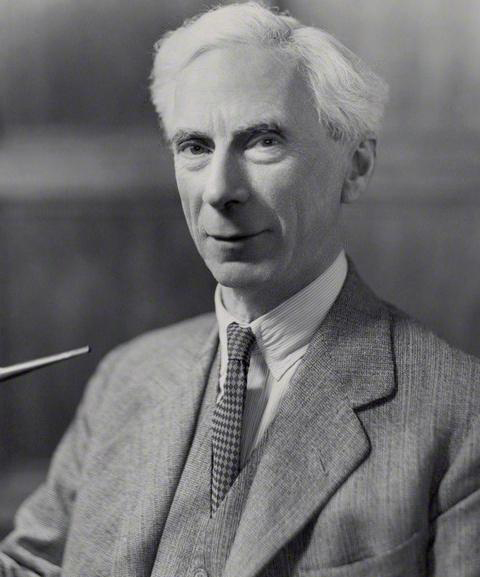

The mathematician Bertrand Russell is another legendary ‘insider’ who wrote popular science and philosophy with erudition and wit, deservedly winning the 1950 Nobel Prize for Literature. In presenting the award, Anders Österling, the Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy, noted Russell’s academic achievements – he was the co-founder of mathematical logic – but this was not what his prize was for; rather, ‘What is important, from our point of view, is that Russell has so extensively addressed his books to [the] public … ’ His popular writing on science, philosophy, politics, and ethics promoted ‘humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought’, according to the Nobel Committee’s citation.

Bertrand Russell, 1936 (Bassano Ltd, via Wikimedia Commons)

Bertrand Russell, 1936 (Bassano Ltd, via Wikimedia Commons)

Promoting public understanding of science as a way of championing such ideals and freedoms has quite a long history, including the works of the radical French Enlightenment poet and playwright Voltaire, and his partner, mathematician Émilie du Châtelet. They are part of a centuries-old tradition of popular science writing, from both inside and outside the academy, which has long been recognised as a vital means of educating and entertaining the public. As Russell’s Nobel Prize attests, popular science has also been valued as literature. Indeed, the British novelist Ian McEwan has suggested the idea of a scientific literary canon (The Guardian, 2 April 2006). Acknowledging that any canon reflects prevailing assumptions and invites challenge, he ventured his own canonical list. It includes Voltaire’s Letters on England, which has some fine pieces about science, including, as McEwan pointed out, an article arguing for the then-new and controversial idea of immunisation. Voltaire’s wit and erudition in the cause of rationality is, like Russell’s, still relevant in these post-truth, anti-vax days.

As a novelist, McEwan really ‘gets’ the literary value of science writing. He says there ‘is a special pleasure to be shared, when a scientist or science writer leads us towards the light of a powerful idea which in turn opens avenues of exploration and discovery leading far into the future ... Some might call this truth. [But it also] has an aesthetic value …’ When I started writing literary popular science, I felt that it was valued this way in Australia, too, and I felt proud to be an acknowledged part of our literary community. Today I’m not so sure.

This is partly because of the chronic underfunding of all the arts, and of cuts to university humanities departments and the linking of STEM education funding to industry, devoid of philosophy and history. There is also the shrinking review space for books in general and popular science in particular, and changes to non-fiction book publishing, all largely in response to the digital financial model that favours headline-grabbing click-bait stories, and to the online world where information abounds, and everyone can be a writer. But it is more than that.

Our literary benchmarks seem to me to have become more parochial, while big, universal scientific stories are mostly relegated to news of the latest ‘breakthrough’, no matter how premature. When these big stories are recognised in literary forums – our festivals, magazines, and awards – the concepts underpinning them are rarely considered intrinsically worthy of attention; rather, the emphasis is increasingly tangential to the science: the political, cultural, and environmental ramifications of scientific technology; nature writing; and ‘self-help’ in the form of science-based tips to improve mental or physical health. Important topics, all. But we live in a scientifically sophisticated society, so we need to understand – and enjoy – the science itself, too. A recent report from the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority found that fewer than half the school students surveyed ‘reported having “in-depth discussions about science ideas” in their science lessons’, and that students have better attitudes to science if they can discuss it outside class, with friends and family. Good popular science writing can help here, both by explaining core ideas and by showing that science is a way of thinking. It is much more than the sum of its parts, the facts.

For McEwan, a literary tradition ‘implies an active historical sense of the past, living in and shaping the present’. Analogously, Ed Yong wrote in The Atlantic (2 October 2021), ‘When done properly, covering science trains a writer to bring clarity to complexity, to embrace nuance, to understand that everything new is built upon old foundations …’

Unfortunately, many gatekeepers, here and abroad, seem to be guilty of presentism; in the case of science, this includes favouring writing that focuses on the latest shiny new tech or interim discovery over intrinsically interesting historical or expository stories that explain and contextualise today’s developments. Still, we have some fine science writers, as NewSouth’s annual Best Australian Science Writing anthologies attest, although even here the emphasis now is on the present, and on description rather than exposition.

On the other hand, many literary novelists include references to science in their fiction, especially to tech and climate change. Yong believes that science and society are now so intertwined that what counts as science writing is up for grabs. He has a point, but it is too broad: emphasising the personal and sociopolitical aspects of science is important, but not a substitute for writing about science itself. I prefer McEwan’s view, that science and science writing themselves have literary value.

In fact, I would go further, as I have tried to show here: literary science writing is worthy not just of a literary science canon, but of a place in ‘the’ literary canon – whatever we define this to be.

This article is one of a series of ABR commentaries on cultural and political subjects being funded by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Comments powered by CComment