- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: New horizons

- Article Subtitle: Narratives of identity and experience

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The slogan the ‘personal is political’ is now so well-worn that it has congealed into cliché, though the notion itself can still produce a backlash if we take regular diatribes against ‘identity politics’ as a measure. In such rants, it is as though only some of us possess an identity that we mobilise around politically, whether under the LGBTQI+ umbrella, as First Nations peoples, as part of ethnic communities, or as ‘women’, the world’s largest special interest group. Given that critics of ‘identity politics’ tend to be socially conservative, the targets of their reductive invectives are presumed to lean to the left politically.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Zora Simic reviews ‘Personal Politics: Sexuality, gender and the remaking of citizenship in Australia’ by Leigh Boucher et al.

- Book 1 Title: Personal Politics

- Book 1 Subtitle: Sexuality, gender and the remaking of citizenship in Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $36.99 pb, 313 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

As Leigh Boucher, Michelle Arrow, Barbara Baird, and Robert Reynolds, the authors of the vibrant new history Personal Politics: Sexuality, gender and the remaking of citizenship in Australia, compellingly demonstrate, ‘the deployment of gender and sexual identities as the central vehicle of citizenship claims’ has not been a feature exclusive to ‘feminist and gay and lesbian politics’. Nor did men’s interest groups suddenly appear on the scene with the advent of Women’s Liberation in the 1970s. Chronologically, they begin in the mid-1960s, when ‘a set of masculinist dissatisfactions’ with amendments to the Matrimonial Causes Act 1959 inspired the formation of the Divorce Law Reform Association (DLRA). Their targets were not feminists, but what they saw as ‘swindling and interfering lawyers and conniving and dishonest wives’.

As the authors narrate in their erudite introduction, Personal Politics traverses the shift from the ‘social liberalism’ of the 1970s and 1980s through to our current moment of ‘late modernity’ or ‘advanced liberalism’, via the ascent of neo-liberalism in the 1990s. To put it in less academic terms, we follow ‘unpaid activists’ in the 1970s campaigning for abortion and homosexual law reform, some of whom became ‘employees in government-funded community services’ and ‘femocrats’ and ‘poofycrats’ devising policy in the 1980s and into the 1990s, on to the ‘campaign professionals’ who were key players in the marriage equality campaign in 2017. Pitched as a ‘cultural history’ and a ‘new political history’, Personal Politics succeeds as both, with the authors consistently pulling off the admirable feat of engagingly narrating the necessary though sometimes inevitably dry details of policy development and political campaigning in tandem with the wider social and cultural changes and aspirations that motivated those involved.

With four authors on board (and with Boucher at the helm), Personal Politics is a remarkably coherent history yoked together by their reframing throughout of ‘personal politics’ as a notion, and an inspired approach to organising the material. The research team are all experts on the topics and themes covered and have individually published books and articles in recent years that overlap with, or are pertinent to, Personal Politics, including Arrow’s The Seventies: The personal, the political and the making of modern Australia (2019) and Abortion Care is Health Care (2023) by Baird. While their previous research clearly informs and strengthens the new book, they also keep things fresh by swapping areas of expertise, sharing research, showcasing recent scholarship, and merging histories they have individually covered elsewhere to yield new insights. For instance, HIV-AIDS activism (earlier historicised by Reynolds) and ongoing campaigns for abortion law reform (Baird’s terrain) are skilfully brought together as emblematic of a shift to ‘health centred activism’ from the late 1980s. Theirs is a convincing authorial ‘we’, particularly in those moments where they critique what forms of ‘personal politics’ have been most successful in mainstream terms, and at whose expense.

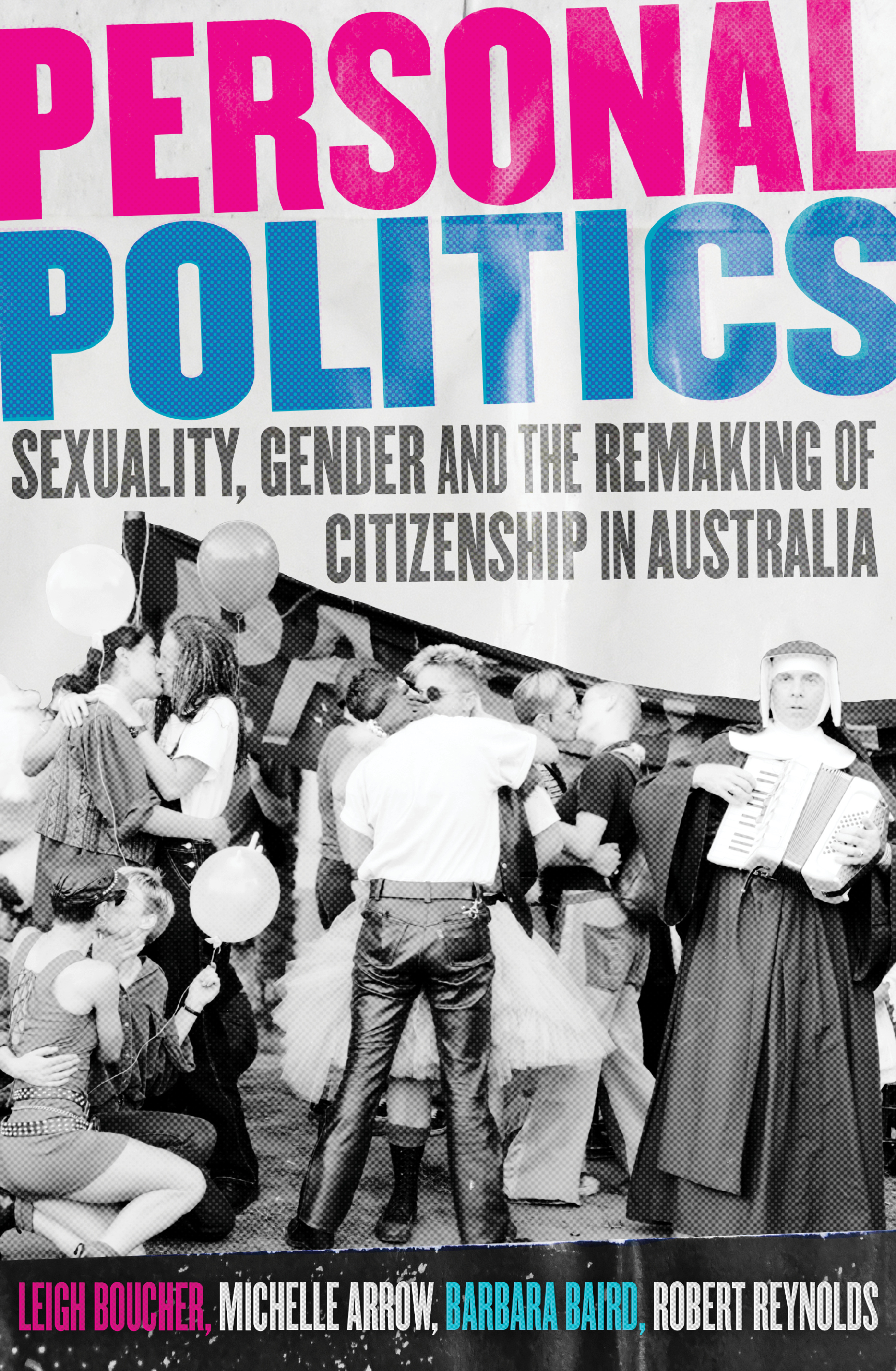

Melbourne rally for marriage equality, 2017, photograph by Paris Buttfield-Addison, (CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Melbourne rally for marriage equality, 2017, photograph by Paris Buttfield-Addison, (CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Most chapters feature an illuminating pair of case studies. Considered together, activist campaigns concerning abortion and male homosexuality in the 1970s ‘reveal a shared refusal of citizenship’s reproductive bargain’. In the same decade, ‘groups representing home-making mothers and working fathers’ mobilised against the new Family Court, sharing a ‘vision of a domestic order’, but ultimately with different ambitions. An especially sobering chapter compares the contrasting fates of the Women’s Refuge Movement, which, despite its early and ongoing efforts, has not managed to fend off the encroaching tides of neo-liberal reforms, and the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, as it was known in the early 1990s, when it successfully recast itself as a profit-making community organisation.

Elsewhere, the ultimately unsuccessful campaign to save the Safe Schools program, after it became the victim of a culture war launched by The Australian, is generatively paired with the less visible but more politically palatable men’s shed movement. If at first glance the comparison seems ‘incongruous, even controversial’, given that Safe Schools aimed to support and empower queer youth while the men’s sheds service (mostly) white, heterosexual men, the two political projects shared a strategy of making appeals based on ‘distress and vulnerability’. The benefits and limitations of such an approach are sensitively pondered. The Safe Schools campaign was one crucial element of the ‘emergence of Trans Youth as a political identity in Australia’, but at the same time the public visibility of queer pain and trauma did not stop the federal government withdrawing funding in 2017. That same year ushered in marriage equality, following an often bruising No campaign which targeted Safe Schools, and a Yes campaign that, while ultimately successful, also divided, or failed to adequately represent, the LGBTQI+ community. The final chapter of Personal Politics boldly takes on this very recent history by examining diverging accounts published in the immediate aftermath of the postal vote.

An afterword comparing the achievement of marriage equality with the failed Voice to Parliament referendum in 2023 is valuable on its own terms, while further emphasising some of the overarching themes and concerns of Personal Politics. These include the fact that the ‘remaking of citizenship’ in Australia is not a progress narrative; that sexuality and gender are fundamental features of Australian political life, in both explicit and implicit ways; and that Australian citizenship and nationalism continue to be racialised and shaped by settler colonialism. If, at times, the last point is made perfunctorily, particularly in relation to migrants and refugees, the effect is an impressively nuanced survey of political campaigns and strategies in which each chapter provides fresh analysis. Finally, beyond its value as history, Personal Politics provocatively and persuasively encourages its readers to contemplate new political horizons, less tethered to narratives of pain and grievance, and which extend beyond the parameters of one’s own identity and experience.

Comments powered by CComment