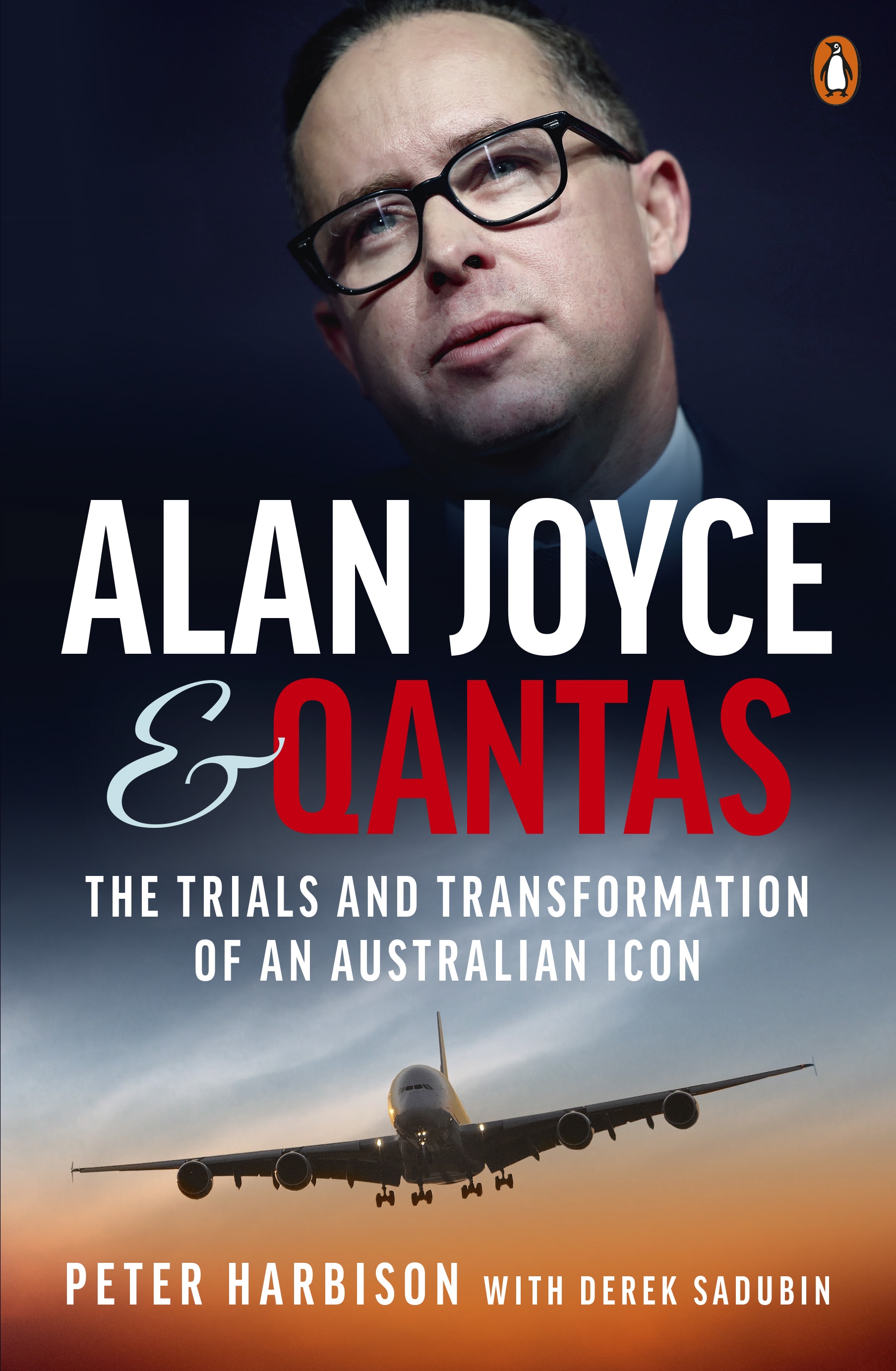

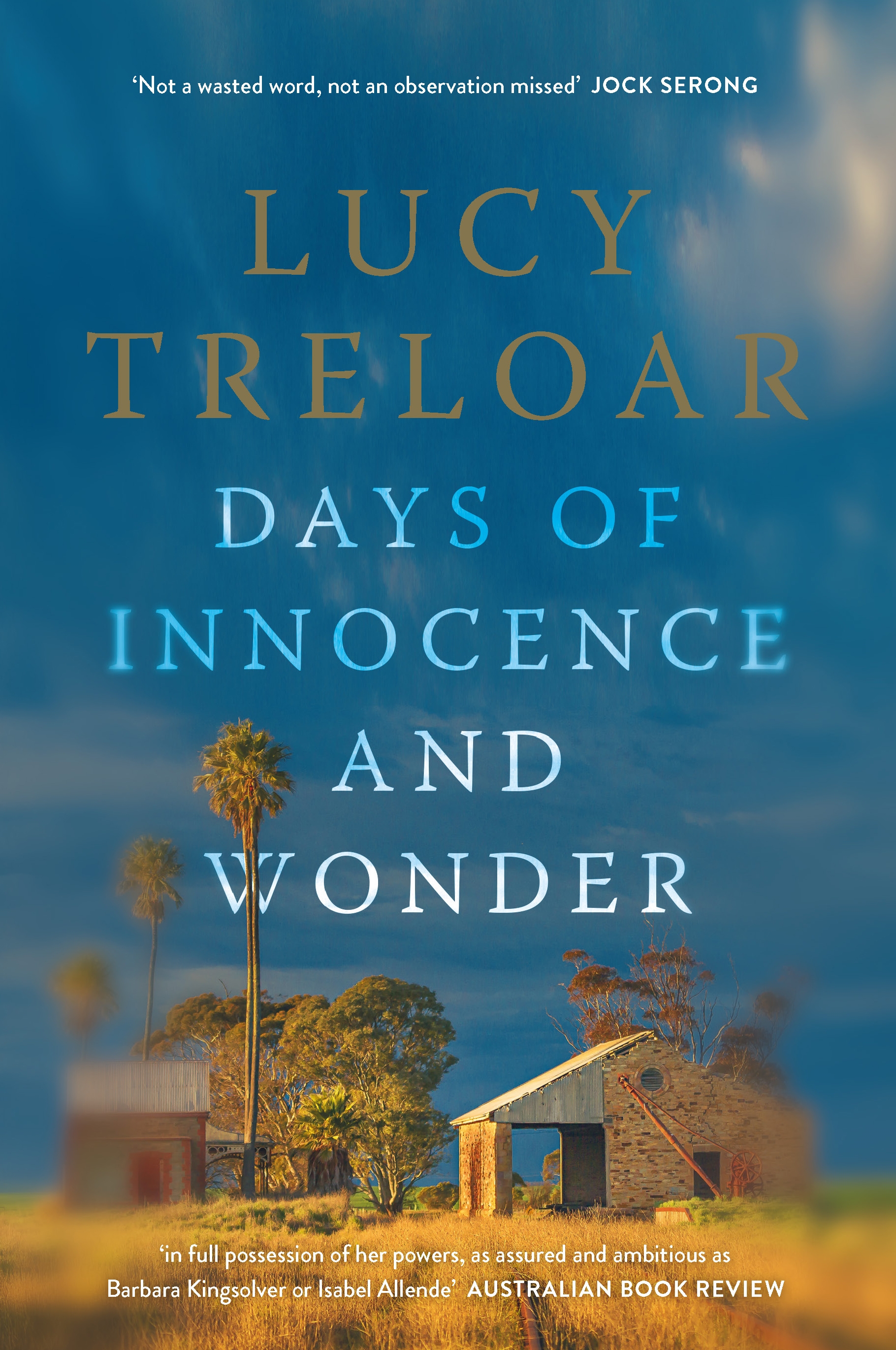

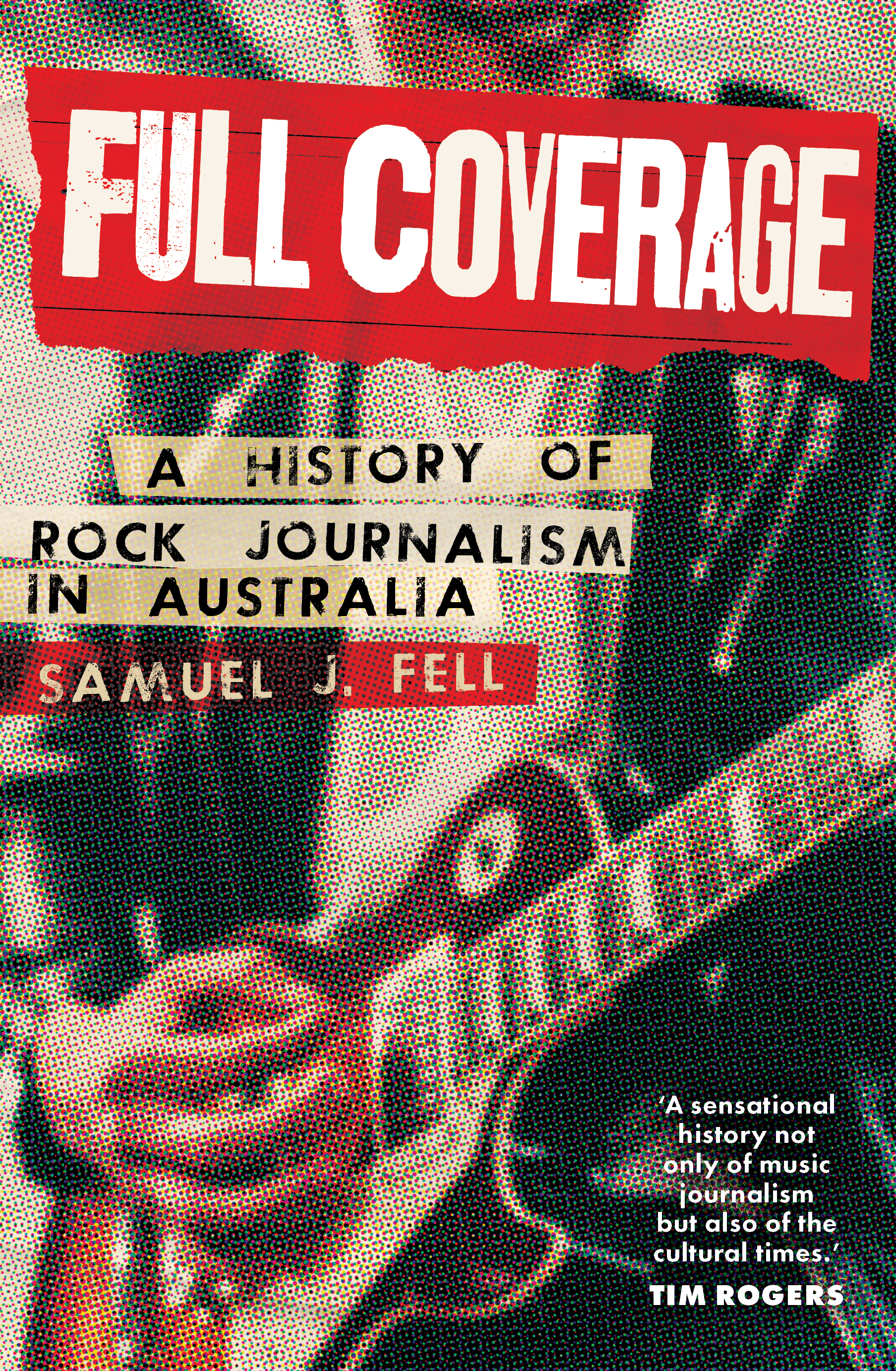

To celebrate the year’s memorable plays, films, television, music, operas, dance, and exhibitions, we invited a number of arts professionals and critics to nominate their favourites.

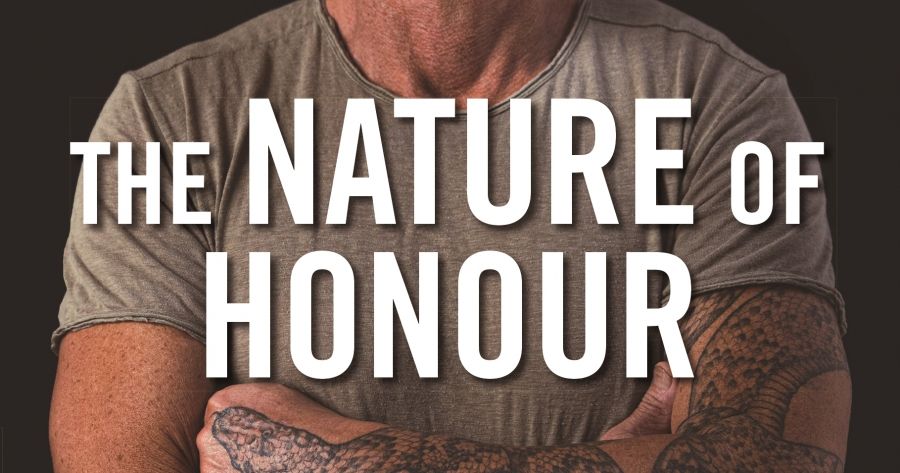

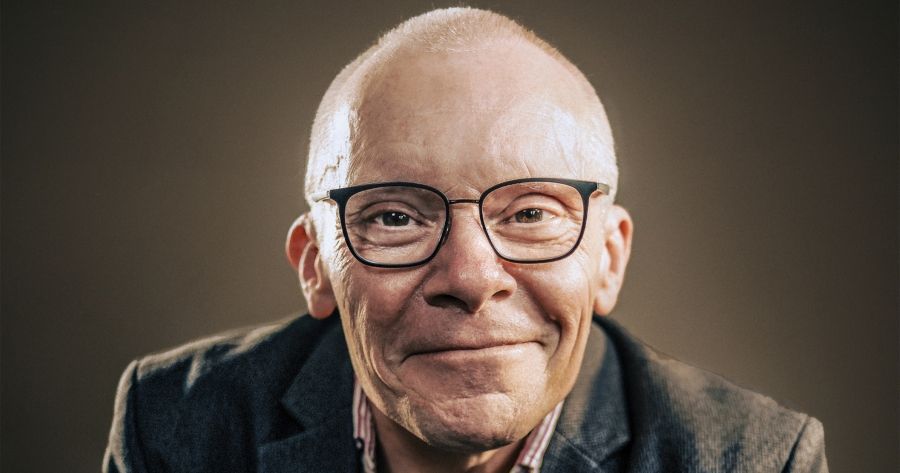

Ian Dickson

Belvoir is ending the year on a roll. In Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar & Grill, Zahra Newman – directed by Mitchell Butel and ably backed by Kym Purling, Victor Rounds, and Calvin Welch – gave us a disintegrating Billie Holiday and turned Lanie Robertson’s mediocre play into a poignant tragedy (Lady Day was reviewed in ABR Arts, September 2023). This was followed by Eamon Flack’s rollicking, genre-busting version of Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita (ABR Arts, 11/23). Flack cleverly juxtaposed the events in the novel with the terrifying background against which it was written. The Sydney Symphony Orchestra’s season also closed with a bang. Simone Young conducted an in-form band and a uniformly strong cast in a concert version of Wagner’s Das Rheingold, which had its audience avid for the next three operas in her Ring Cycle. Earlier in the year, Musica Viva’s Paul Kildea took John Cage’s Sonatas and Interludes for prepared piano, enlisted the composer and sound artist Matthias Schack-Arnott to create and light a sculpture that rotated as Cédric Tiberghien played, and provided an experience that had an extraordinary, almost spiritual effect on the audience.

Zahra Newman in Lady Day (photograph by Matt Byrne)

Zahra Newman in Lady Day (photograph by Matt Byrne)

Robyn Archer

In the wake of Ryuichi Sakamoto’s untimely death in March 2023, Shiro Takatani (member of the company Dumb Type, which has graced a number of Australian festivals) created a new version, async – immersion 2023, of his collaboration with Sakamoto. Specifically designed for the vast dark industrial basement of the Shinbun Kyoto building in this year’s Ambient Kyoto, and blending Sakamoto’s music in exquisite three-dimensional sound with Takatani’s seemingly endless sequence of images (including landscape, library, seascape, Sakamoto’s work tools and a piano wrecked by the 2011 tsunami, which reignited Sakamoto’s anti-nuclear activism) and their digital manipulation, this work exemplifies everything that a massive screen-based immersion can achieve: meditative, reflective, technically faultless. In the ninety minutes I spent there, only one image was repeated and then in different format: I could have stayed there all day.

Ryuichi Sakamoto (Flickr via Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license)

Ryuichi Sakamoto (Flickr via Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license)

Diane Stubbings

Trophy Boys (fortyfivedownstairs), a play about male toxicity in a high-school debating team, was independent theatre at its best. Written by Emmanuelle Mattana and directed by Marni Mount, the play’s sexual politics may have been simplistic, but it had a vitality that few of Melbourne’s mainstage productions could muster. Richard Mosse’s Broken Spectre, a video installation at the National Gallery of Victoria which juxtaposed the extraordinary beauty of the Amazon rainforest with its seemingly inexorable destruction, was transformative. So too Jonathan Glazer’s unflinching perspective on the enablers of the Holocaust in his film The Zone of Interest (ABR Arts, 11/23). For the duration of its four short minutes, The Beatles’ ‘Now and Then’ moves you through a kaleidoscope of long-lost emotions. The cadences of Lennon’s vocals, the supporting strains of McCartney, Harrison, and Starr, are both immediate and hauntingly remote. While some might question the song’s musical qualities, there are few who won’t remember it as a watershed moment in the synthesis of AI and the arts.

The Zone of Interest (courtesy of the Jewish International Film Festival)

The Zone of Interest (courtesy of the Jewish International Film Festival)

Peter Rose

For consistency of singing, for dramatic cohesion, for no-nonsense directorial vision, and for sheer chutzpah, Melbourne Opera’s production of Wagner’s Ring Cycle (ABR Arts, 3/23), performed in Bendigo (without state government support, shamingly), was a clear highlight – pound for pound the finest Ring I have seen in Australia. Meanwhile, the national company remained on mute in Melbourne. In Sydney, Opera Australia presented La Gioconda in concert, a welcome reminder of the riches in Ponchielli’s often-maligned opera (ABR Arts, 8/23). Ludovic Tézier stole the show – a masterclass for baritones. October took us to Europe for ABR’s Vienna tour, the highlight of which was Strauss’s magnificent, preposterous opera Die Frau ohne Schatten at the Vienna State Opera, superbly conducted by Christian Thielemann (ABR Arts, 10/23). Simone Lamsma was an inspired soloist in Britten’s Violin Concerto with the Wiener Symphoniker, under Jaap van Zweden (ABR Arts, 10/23). Earlier, the great Maxim Vengerov tore down the Concertgebuow with a mighty rendition of Brahms’s Violin Concerto (ABR Arts, 10/23).

The cast of La Gioconda with the Opera Australia Orchestra (photograph by Keith Saunders)

Julie Ewington

Notes from a year when Australia’s increasingly complex social and cultural dialogues were manifested in generous projects exploring difference and community. Among the best: Between Waves, the third Yalingwa exhibition of First Nations artists at ACCA, Melbourne, ‘shining a light on our times’: beautiful, limpid, intelligent. Wonderful solo outings include the (overdue) institutional exhibition for Newell Harry, subtitled Esperanto, at MAMA, Albury; Iranian-Australian Hoda Afshar’s exceptional photographs and videos at AGNSW (until 21 January 2024); and Camille Laddawan, at Sydney’s Australian Design Centre, currently showing exquisite small weavings with glass beads that chart the diverse inheritances of her unborn child. Further afield, a first visit to M+, Hong Kong’s brilliant global museum of contemporary art, film, design, and popular culture. M+ is engaging, expansive, a conduit between peoples and cultures; half the visitors are from mainland China, and clearly they are captivated. Finally, a lifetime wish fulfilled: Matisse’s luminous Chapel of the Rosary in Vence, near Nice. Wonderful in any year.

Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence, also known as the Matisse Chapel (photograph by Michel Baret and Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence, also known as the Matisse Chapel (photograph by Michel Baret and Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Malcolm Gillies

The Vision String Quartet, which toured in September–October for Musica Viva, was just fantastic. This young ensemble from Berlin directly fronted its audience. How? By playing its programs entirely from memory. Gone were rickety music stands, or even sleek iPads. Their Fourth Quartet of Bartók was technically brilliant, appropriately stylish, and gripping. Another showcase of youthful talent was the Sydney International Piano Competition’s romp, from opening gala to grand-final culmination (ABR Arts, 7/23). This was the first fully staged Competition in seven years; the reincarnation was broadcast online under the management of Piano-Plus. In fact, 2023 was the year of growing market penetration of digital concert halls, purveying specialist, regional, community, and youth arts like never before. No longer, it appears, does quality music need to be geared to high-paying ‘urban élites’. As university students have deserted draughty lecture halls, are our concert highlights also now best found in the cloud?

From the Opening Gala of the Sydney International Piano Competition (photograph by Jay Patel)

From the Opening Gala of the Sydney International Piano Competition (photograph by Jay Patel)

Clare Monagle

In January 2023, I saw the Red Line production of Amadeus at the Sydney Opera House and I’m still pinching myself that I experienced its sheer Sydney splendidness (ABR Arts, 12/22). Every element was exciting. Michael Sheen was the iconic star of the stage I had hoped for. The actor who had once played Mozart to David Suchet’s Salieri was now the older jealous composer, burning with resentment at the youngster’s genius. The costumes, by Romance Was Born, were garishly Sydney while still being quite eighteenth century. But the highlight was that the production contained musicians from the Metropolitan Orchestra. Most productions of Amadeus have relied on recorded music. It was a rare treat indeed to test the new acoustics of the renovated Concert Hall, with snippets of Mozart as part of a big and joyfully bombastic theatrical production.

Michael Sheen (courtesy of Red Line Productions)

Michael Sheen (courtesy of Red Line Productions)

Andrew Ford

I heard both the Alma Moody Quartet and the Australian Romantic and Classical Orchestra live for the first time (ABR Arts, 8/23). The former played Ligeti, the latter Mendelssohn, and both delivered revelations. Mendelssohn’s Scottish symphony seemed more a masterpiece than ever. Hoda Afshar’s photographs at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (A Curve is a Broken Line) took my breath away. I walked into the room of giant black-and-white photographs of hair-braiding and doves, and felt utterly elated. Turn Every Page, a film about biographer writer Robert Caro (The Power Broker, The Years of Lyndon Johnson) and editor Robert Gottlieb, ought to be impossibly dry, but, lovingly directed by Gottlieb’s daughter, it’s my film of the year. I watched it flying to England, then flying back, and twice more since. I have told everyone I know they should watch it, too; I’m not sure they always believe me.

Australian Romantic & Classical Orchestra conducted by Rachael Beesley (photograph by Peter Hislop)

Australian Romantic & Classical Orchestra conducted by Rachael Beesley (photograph by Peter Hislop)

Felicity Chaplin

Watching Alice Rohrwacher’s mesmerising The Wonders under the stars on a balmy July night in Florence at the open-air Apriti Cinema in the Piazzale degli Uffizi. Greatly anticipating and then seeing her next film, La Chimera (ABR Arts, 9/23), which completed her trilogy including The Wonders and Lazzaro Felice, all set in her homeland of central Italy and all shot with poetic febrility and technical imperfection by Hélène Louvart. MIFF’s impressive program also included the following outstanding films by women: Marie Amachoukeli’s tender, delicate, and inventive Àma Gloria; Justine Triet’s suspenseful courtroom drama Anatomy of a Fall, an enthralling dissection of marital intimacy with the masterful Sandra Hüller in the lead role; and Alice Englert’s feature film début, the astutely observed black comedy Bad Behaviour, starring Ben Whishaw and the brilliant (and underrated) Jennifer Connelly, followed by an engrossing late-night Q&A with the director.

La Chimera (courtesy of Palace Films)

La Chimera (courtesy of Palace Films)

Des Cowley

Saxophonist Adam Simmons and Italian pianist Alessandra Garosi delivered an outstanding recital – brimming with masterful improvisation – at Tempo Rubato, freely interpreting Italian composer Damiano Santini’s extended suite Zodiac. The evening felt bittersweet, as Simmons announced his retirement from professional playing. Trumpeter Reuben Lewis’s solo performance at the Primrose Potter Salon proved thoroughly hypnotic, his ambient soundscapes elevated by the presence of dancer Tony Yap. And on a balmy Cup Eve, Nick Tsiavos entered the intimate confines of the La Mama Courthouse, in Carlton, to play his extended piece for solo bass Maps for Losing Oneself, at once austere, timeless, and searingly beautiful. Lastly, the Melbourne Jazz Co-operative’s fortieth-anniversary concert at the Melbourne Recital Centre in May – featuring performances by Mike Nock, Vanessa Perica, Sandy Evans, Paul Grabowsky, Andrea Keller, and dozens more – marked a genuine milestone, celebrating contemporary Australian jazz, along with the indefatigable efforts of its founder Martin Jackson (ABR Arts, 5/23).

Vanessa Perica at the Recital Centre for the Melbourne Jazz Co-operative 40th-anniversary concert (photograph by Will Hamilton-Coates)

Vanessa Perica at the Recital Centre for the Melbourne Jazz Co-operative 40th-anniversary concert (photograph by Will Hamilton-Coates)

Tim Byrne

Post-Covid, the performing arts are struggling to fully recover – with the greatest devastation wrought on the independent sector. Perhaps this is why the best shows this year came from our larger companies, and one small company that went large. Nikki Shiels brought the flinty, firebrand arts patron Sunday Reed to glimmering life in Anthony Weigh’s thoughtful, incisive three-hander, Sunday, for MTC. David Hallberg put his mark on the Australian Ballet with a glorious Swan Lake, sumptuous and deeply symbolic. His pairing of Benedicte Bemet with Joseph Caley is a triumphant one for the ages. And Melbourne Opera delivered Der Ring des Nibelungen in Bendigo, epic and intimate. Suzanne Chaundy’s direction was clarion and her singers, led by Warwick Fyfe and Antoinette Halloran, superb. It made the heart swell with pride.

Sunday (courtesy of MTC and photograph by Pia Johnson)

Sunday (courtesy of MTC and photograph by Pia Johnson)

Sophie Knezic

Bare bodies – animated by choreographic contortions or the more understated gestures of intimacy and repose – characterised several contemporary exhibitions this year. Paul Knight’s ongoing photographic series Chamber Music (exhibited in L’ombre de ton ombre at MUMA), documenting intimate life with his long-term partner, exuded a post-coital tenderness, while Lucy Guerin’s NEWRETRO – excerpts from her choreographic back-catalogue (‘21 works, 21 dancers, 21 years in the making’) – had dancers tumbling gracefully across ACCA’s cavernous interior. The most compelling bodies, however, were the brooding figures set in post-apocalyptic environments envisioned by Peter Booth. A spectacular survey at TarraWarra Museum of Art assembled paintings and drawings produced over four decades, collectively creating a mood of nightmarishness and angst. Icy landscapes set aflame against leaden nocturnal skies were the harsh backdrops for despondent, often grotesque, figures trudging through a sepulchral world.

Peter Booth, Painting Two 1984 (National Gallery of Victoria via TarraWarra)

Peter Booth, Painting Two 1984 (National Gallery of Victoria via TarraWarra)

Michael Shmith

For a few weeks in March and April, Bendigo became the Bayreuth of the Great Southern Land. To all those who made the pilgrimage to the Ulumbarra Theatre, Melbourne Opera’s first complete production of Der Ring des Nibelungen was a worthy and engrossing experience. Through Anthony Negus’s superbly controlled and paced conducting and Suzanne Chaundy’s straightforward and vividly telling production, Wagner’s tetralogy did not seem a second too long; rather, it emerged as a true festival piece in which the days between the operas were, like the silences in music, periods of reflection and anticipation. I was at the second of the three cycles. Especially distinguished performances were Warwick Fyfe’s lyrical and bellicose Wotan, and Bradley Daley’s untiring Siegfried, whose sweetness and strength of tone reminded me uncannily of the great Heldentenor Siegfried Jerusalem, who happened to be sitting next to me.

What next for Melbourne Opera and Bendigo? Maybe Die Meistersinger?

Darren Jeffrey, Warwick Fyfe, Steven Gallop, James Egglestone, Chris Tonkin, Sarah Sweeting, Jason Wasley and Lee Abrahmsen in Das Rheingold (photograph by Robin Halls)

Darren Jeffrey, Warwick Fyfe, Steven Gallop, James Egglestone, Chris Tonkin, Sarah Sweeting, Jason Wasley and Lee Abrahmsen in Das Rheingold (photograph by Robin Halls)

Jordan Prosser

In a year beset by grim omens for the entertainment industry, including not one but two Hollywood strikes, the Melbourne International Film Festival once again proved an oasis in a desert of shifting release schedules and lacklustre streaming content. Two films stood out. In Anatomy of a Fall, the Palme d’Or-winning French courtroom drama from director Justine Triet, a steely Sandra Hüller plays an author accused of murdering her husband, leading to a gruelling forensic examination of her marriage. And in May December, Todd Haynes’s gleefully murky melodrama, Natalie Portman plays a ruthless actress studying every move and mannerism of Julianne Moore’s soft-spoken matriarch, who became infamous twenty years earlier for her tabloid romance with a thirteen-year-old boy. Portman and Moore are in career-best form, but the real revelation here is Riverdale’s Charles Melton as the now-grown husband, sending his own children off to college when he himself was robbed of a normal adolescence.

From May December (courtesy of Transmissions Films)

From May December (courtesy of Transmissions Films)

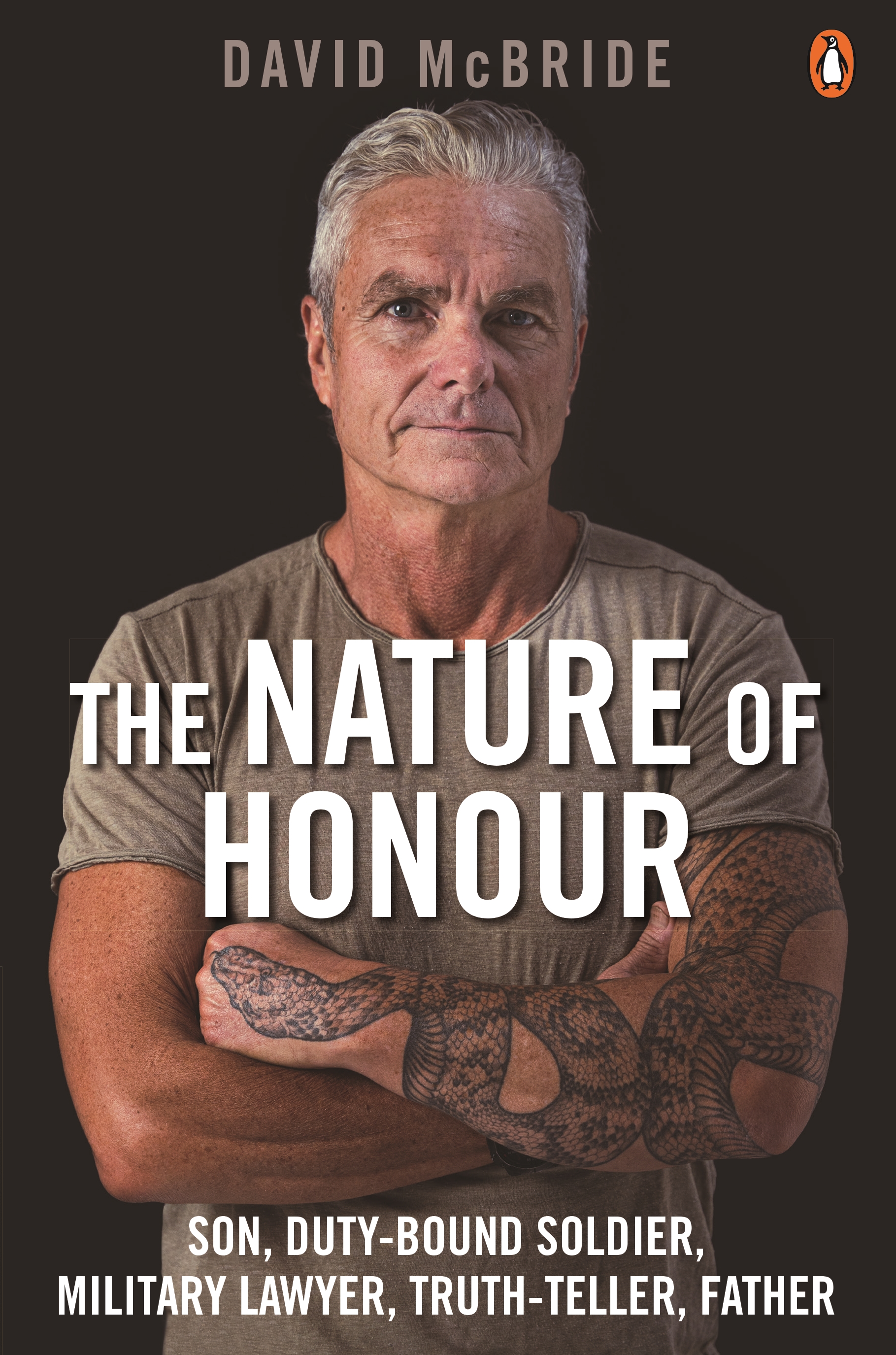

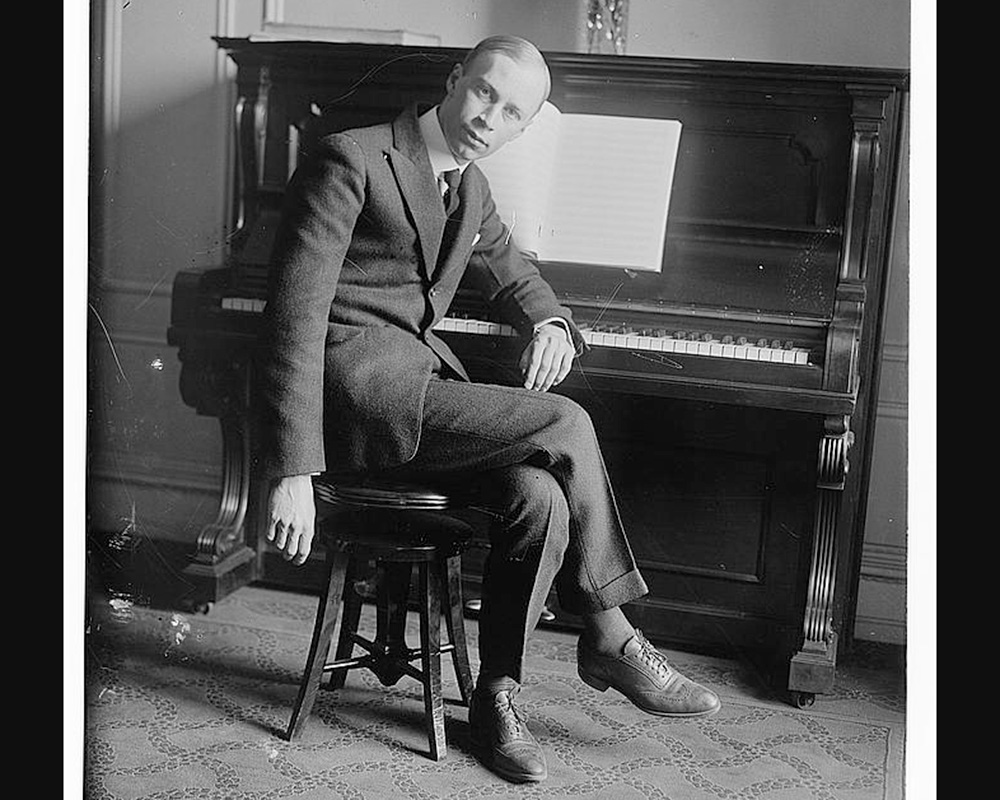

John Allison

Problematic at the best of times, Prokofiev’s War and Peace (ABR Arts, 7/23) is a powerful if ramshackle opera with roots in Stalin’s propaganda ministry. Now, in far from the best of times, the Bayerische Staatsoper must have wondered whether its long-standing plan to stage it was wise, but the company and the work itself were vindicated when the conductor Vladimir Jurowski and director Dmitri Tcherniakov – both Russians living abroad, both critics of Putin’s regime – teamed up and, with a large cast drawn across the states of the former USSR, delivered the most blazingly brilliant operatic performance of the year. Not far behind it in terms of epic power was Lydia Steier’s production of Verdi’s Don Carlos at the Grand Théâtre de Genève – set in a modern totalitarian state, sung in French (of course), and the fullest text I’ve encountered in the theatre. With an outstanding cast and conducted by Marc Minkowski, every minute blazed with musico-dramatic intensity.

Sergei Prokofiev (photograph from George Grantham Bain Collection in US Library of Congress)

Sergei Prokofiev (photograph from George Grantham Bain Collection in US Library of Congress)

Ben Brooker

Two extraordinary women, one young, one old, were behind the work which most uplifted my sprits in a year that too often confirmed the worst of humanity. On the one hand were three productions written by Caryl Churchill – Patalog Theatre’s Far Away at fortyfivedownstairs (ABR Arts, 7/23) and the double-bill of Escaped Alone and What If If Only at MTC (ABR Arts, 8/23). All three affirmed the now eighty-five-year-old British playwright as perhaps the most vital of her generation, an experimentalist but a humanist at heart, raking through darkness in search of light. On the other hand, the mixed bag that was this year’s Rising Festival at least delivered my musical highlight of 2023 in the form of a breathtaking show by American singer-songwriter Weyes Blood at the Forum. Touring her superb new album And in the Darkness, Hearts Aglow, Blood stunned the packed house with her sublime chamber pop and Linda Ronstadt-esque vocal prowess.

Alison Whyte and Darcy Sterling-Cox in Far Away (photograph by Cameron Grant)

Alison Whyte and Darcy Sterling-Cox in Far Away (photograph by Cameron Grant)

Michael Halliwell

My highlight was the outstanding production by the Bavarian State Opera of Sergei Prokofiev’s large-scale opera based on Tolstoy’s War and Peace. It is a troubling work, particularly with the war in Ukraine not far away, but the Russian team of conductor Vladimir Jurowski and director Dimitri Tcherniakov unflinchingly confronted the Zeitgeist with a setting comprising refugees who ‘play act’ the events of the opera, thus distancing the most offensive Stalinist elements in the opera. A brilliant young cast, led by a Ukrainian soprano and Russian baritone as Natasha and Andrei, did full justice to the work. Opera Australia’s co-production of Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffmann (ABR Arts, 7/23) was a brilliantly quirky staging by an Italian creative team, the vocal highlight being soprano Jessica Pratt. Rounding out the year was polymath William Kentridge’s heartwarming contemporary take on the Cumaean Sibyl myth with an energetic cast of South African singers and dancers: Waiting for the Sibyl (ABR Arts, 11/23).

Sibyl (photograph by David Boon)

Sibyl (photograph by David Boon)

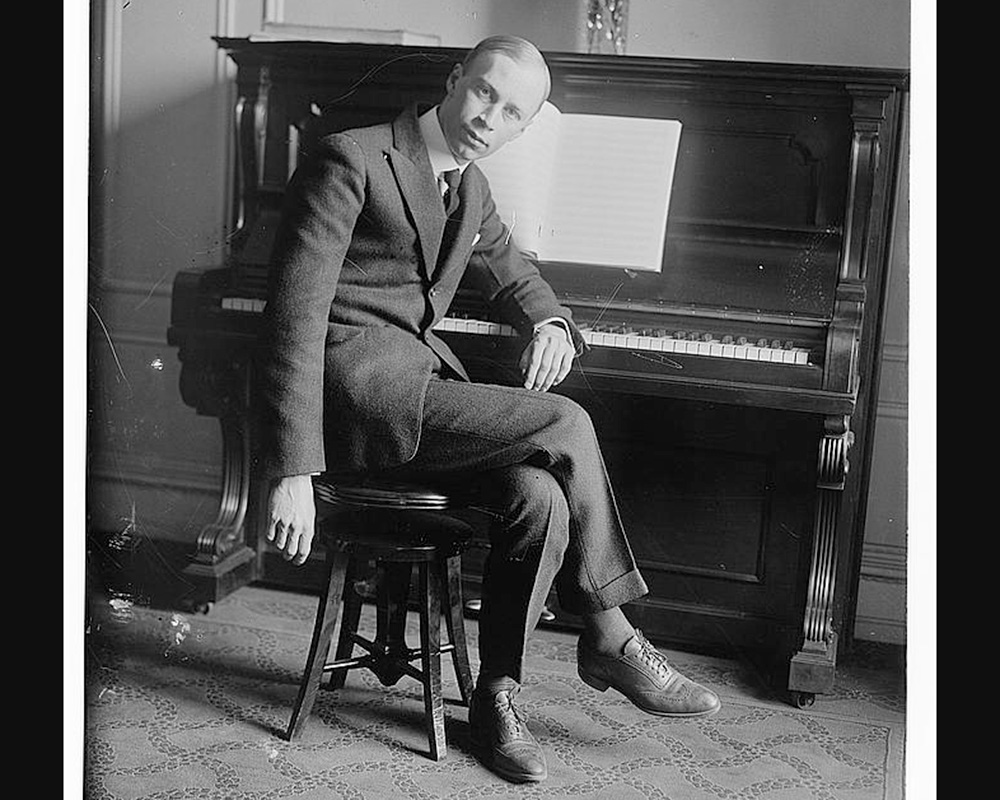

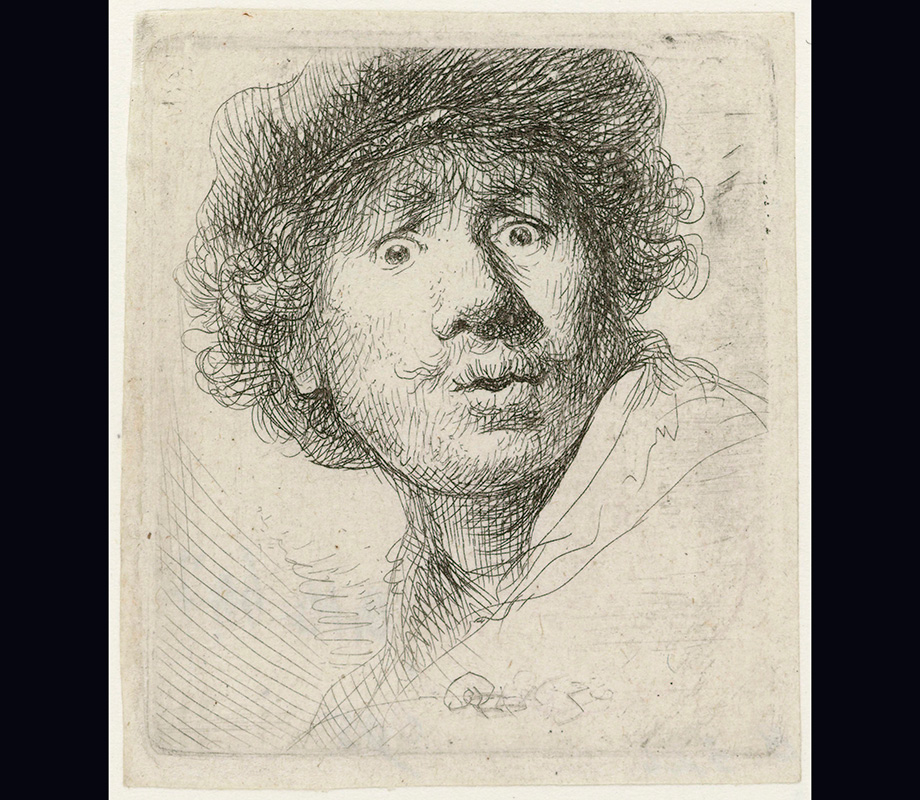

Peter Tregear

My two highlights were encounters with the very small and the very large. The latter was Melbourne Opera’s presentation of Wagner’s Ring Cycle in Bendigo, a mammoth logistical and artistic challenge admirably and successfully undertaken by a company that operates without government subsidy. An effective, narrative-driven staging from director Suzanne Chaundy and designer Andrew Bailey, was well supported by conductors Anthony Negus and David Kram, and by an excellent all-Australian cast. Bendigo’s Ulumbarra Theatre also proved to be a superb venue for this imposing festival of music drama. The former was the NGV’s Rembrandt: True to Life exhibition (ABR Arts, 7/23). Nothing immediately grandiose about the works on display here, many of which were also very small – but they packed a punch. Kudos to curator Petra Kayser for allowing them to bear witness to the artist’s technical and aesthetic brilliance, and his history and humanity.

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, Self-portrait in a cap, 1630, wide-eyed and open-mouthed (Rijksmuseum via National Gallery of Victoria)

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, Self-portrait in a cap, 1630, wide-eyed and open-mouthed (Rijksmuseum via National Gallery of Victoria)

Graham Strahle

Simon Trpčeski’s piano recital in November was for me the year’s most exhilarating concert in Adelaide. This Macedonian pianist played at the level of free-flowing inspiration and daring one felt lucky to witness. His Mozart was wickedly effervescent and cheeky, his Tchaikovsky almost unbearably passionate (the ‘Pas de Deux’ from Nutcracker brought tears to many an eye), and his Prokofiev frankly held one in disbelief by its stupendous roar of virtuosity. This makes it two in a row for Guy Barrett’s Harris International Piano Series, following Robyn Archer’s praise for Jean-Efflam Bavouzet last year, in the same series. Jordi Savall and Hespèrion XXI similarly exceeded themselves at Ukaria in February. Despite a string breaking on Jordi’s treble viol, this esteemed Spanish group turned in its most rapturous consort-playing one could remember, highlighted by gorgeous solo dancing from one of its players, Lixsania Fernández.

Simon Trpceski (photograph by Ealovega Kultur)

Simon Trpceski (photograph by Ealovega Kultur)