- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Young Adult Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Speak louder

- Article Subtitle: Three Young Adult novels by Indigenous writers

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

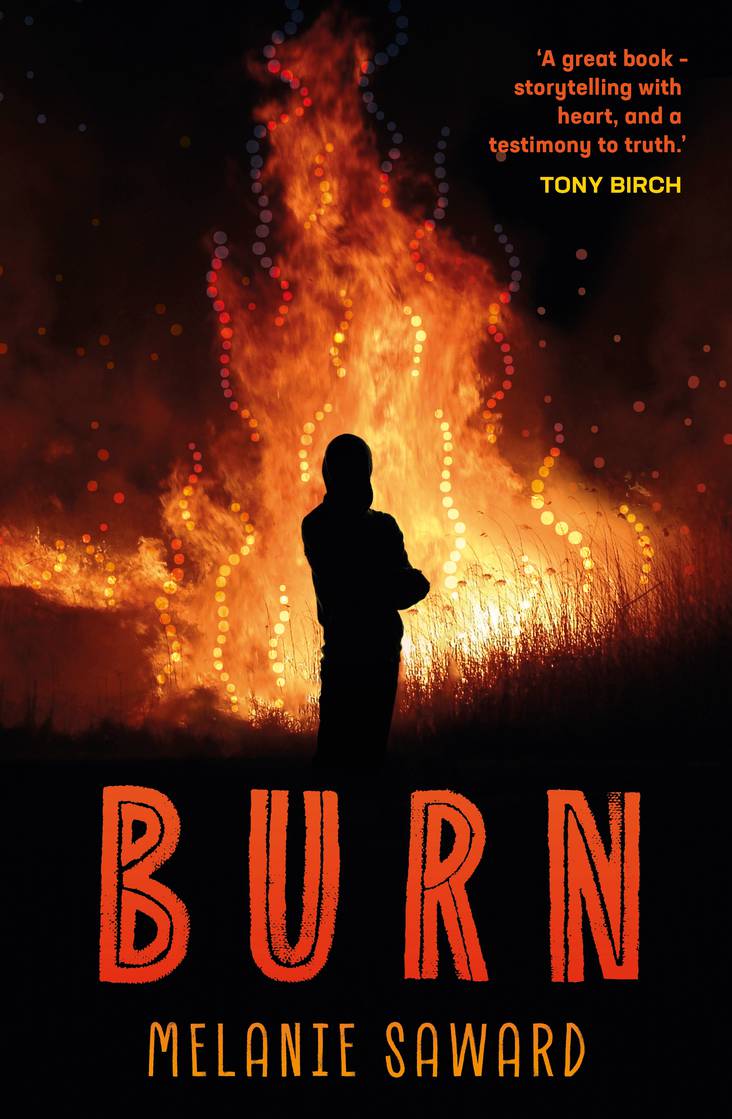

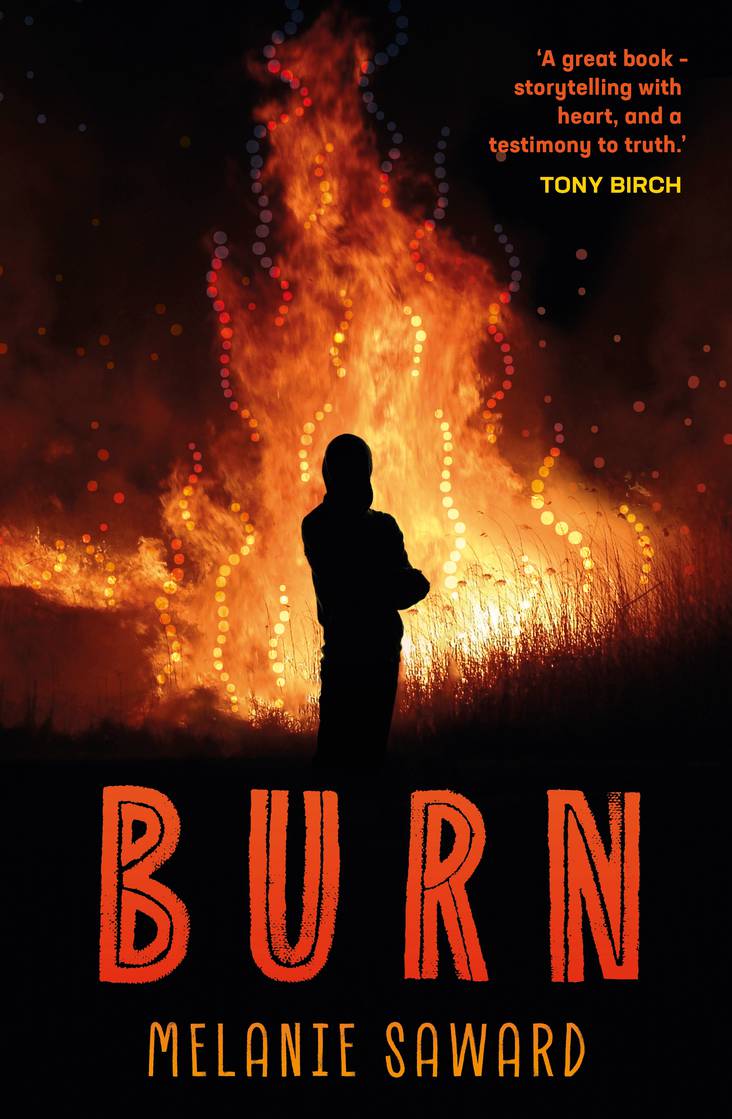

Melanie Saward, a Bigambul and Wakka Wakka writer living in Tulmur (Ipswich), is a fresh and insightful storyteller. Her first Young Adult novel, Burn (Affirm Press, $34.99 pb, 296 pp), is a tumultuous narrative about an Aboriginal youth, Andrew, and his obsession with lighting fires. It has a touch of Trent Dalton’s Brisbane struggle street, but the story draws us into psychological observation in Goori Andy’s cries for help and his longing for his parent’s attention. The novel begins with a bushfire lit by an unknown arsonist, in which a boy dies. This tragedy frames the narrative as we go on the journey with Andy and his mates Trent and Doug, wild teenagers who like to smoke dope and eat at McDonald’s. They are innocents in a world that ignores them as the author interrogates relationships between the lads and several irresistible young females.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Julie Janson reviews three Young Adult novels by Indigenous writers

- Book 1 Title: Burn

- Book 1 Biblio: Affirm Press, $34.99 pb, 296 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

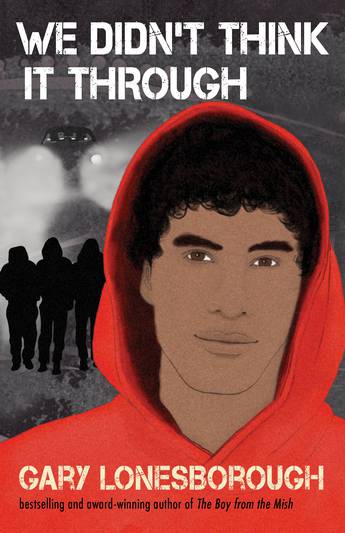

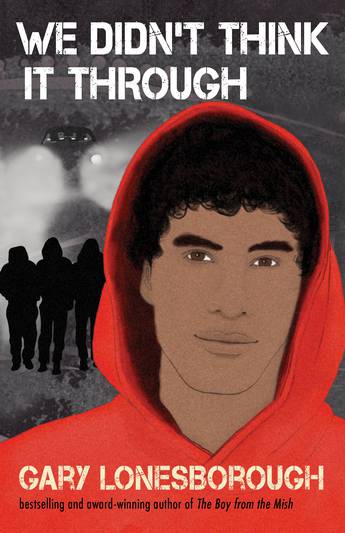

- Book 2 Title: We Didn’t Think It Through

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen and Unwin, $19.99 pb, 300 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 3 Title: Borderland

- Book 3 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $22.99 pb, 236 pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

A sense of despair runs through the daily account of Andy’s life at high school, with occasional glimpses of kindness from friends or teachers. He is not alone, but his inner world hides the truth of his desire to burn everything down, a terrible addiction to the smell of smoke and sound of hissing fire.

Saward is outstanding in evoking the young Aboriginal protagonist’s needs. She takes us inside his head and heart. The touch of the lighters has a palpable sensation. This is impressive writing, where our consciousness merges with the young Andy and his pathetic life with neglectful parents. ‘I’ll see my dad soon and that’s all I care about. I reach into my pocket and run my finger over the purple Bic lighter.’

Redemption comes with Andy’s extended family, and a clarifying essence of the pain of intergenerational trauma. Burn ends stunningly, leaving us certain of hope.

Another Young Adult novel by a gifted First Nations Yuin novelist is We Didn’t Think It Through by Gary Lonesborough (Allen and Unwin, $19.99 pb, 300 pp). What a revelation this young writer is. He is doing something no other male First Nations novelist has attempted: the YA Blak queer genre that is a glimpse into another world view, at once confronting yet heartwarming.

Lonesborough’s grasp of Koori vernacular and of the closeness of Koori families resonates through his story. We are thrust into the terrible reality of Aboriginal incarceration. ‘Don Dale’ echoes in our heads. We hear of the breakdown between fathers and sons, and of the never-ending love of Koori aunties. We hear terror and poetic skill:

‘I run into the blackness, the red and blue spilling over me. Hudson’s heavy boots pound away on the dirt behind me.’

‘I can’t stand the sight: Big men/ Beating the hell out of/ Small boys.’

‘In ‘ere, I can kick back with my mates, I get free food …’

Jamie Langton’s time in detention is poignant, with the recounting of how a poem by Oodgeroo Noonuccal saved him. The description of the Koori Christmas in juvie made me cry.

Homophobia, racism, decolonisation, poetry to save yourself: all are examined through the prism of the novel. There are references to identity, sexuality, emotional men, and a celebratory emergence of Black homonormality within Australia’s post referendum reality.

Psychological and Indigenous social nakedness is explored by the author’s extraordinary ability to tap into our national psyches at a primal level. All of us are touched by the everyday evil of our prison systems against children and by the hatred meted out to the race that suffered colonial slaughter.

Reading on, I cry again at the flashback of Jamie’s mum hugging him while Family Services officers supervise parental visits. There are cinematic scenes as the boys are taken from their parents by authorities. Yet one social worker says: ‘You’ve got a voice inside you, Jamie … I think poetry might be the way for you to let that voice speak louder.’

Jamie and his brother go to live with Aunty Dawn. I cry again when Jamie is home from ‘juvie’ and his schoolteacher reads aloud his poem ‘The Dark Place’. The class cheers. It is the moment when a writer is born. ‘They’re not making fun of me they’re cheering for me.’

We Didn’t Think It Through is further evidence of Lonesborough’s immense talent. We look forward to his future in adult fiction.

The third Young Adult novel is Borderland by Graham Akhurst (UWA Publishing, $22.99 pb, 236 pp). Akhurst, the first Indigenous Australian recipient of the prestigious Fulbright Scholarship, lives on Gadigal country and is from the Kokomini of Northern Queensland.

Borderland, an eco-horror-gothic speculative novel written in a visceral first-person voice, leads us into unfamiliar territory. It’s a crazy ride into the realm of Indigenous identity, the impact of colonisation, and mind-bending imagination.

Jono, a seventeen-year-old city-born Murri, lives with his loving Aboriginal mother and has had a private school education at St Lucia in Brisbane. Life is sometimes challenging – he is beaten up by some jealous young Blackfellas. As a college student, he accepts an acting job in the outback, but this becomes strange and complicated as he is driven to find out about a sacred land and its mining challenges. Jono is ashamed that he didn’t even ‘know who my mob or where my County was’. He arrives in the desert Queensland outback town of Gambari, accompanied by his best friend, Jenny. Jono is haunted by panic attacks not eased by medication. He experiences death omens and fearful apparitions.

Alongside the frightening encounters, we see the protagonist’s inner struggles, his sexual and romantic longings and disappointments. Jono and Jenny find employment with a mining gas fracking venture, and their role is to create a documentary to promote the benefits of the mine to Aboriginal landowners. This concept is fraught with disaster both spiritual and real. A malevolent Dreaming spirit attacks Jono as the mining venture tramples on sacred sites. The beast follows Jono with its ‘long teeth, pale skin. Long claws and black eyes.’ His magpie totem manifests as a warning, and he becomes the spirit, half-man, half-bird. Jono arms himself with a nulla nulla to confront the evil spirit Wudan and Jono incants: ‘from the earth, blood, portent of death’. This a gripping read, a horror story strongly resonant of speculative fictional First Nations stories. ‘The beast was howling at a large full moon and the light cast a bright sheen on its pale body. It focused its black eyes on me, raised its muzzle and sent a piercing howl towards the stars.’

The story is too brief in its coverage of the consequences of fracking; a tougher political edge would have enhanced the impact. Nonetheless, the novel sweeps the reader along with family secrets about heritage emerging from the interactions between the city characters and the older First Nations people on their traditional Queensland homelands. It is a terrific read.

Comments powered by CComment