- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Box

- Article Subtitle: A personal account of imprisonment

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Sean Turnell is an Australian economist who was detained by Myanmar’s military regime from February 2021 until November 2022. An Unlikely Prisoner, his account of the ordeal, has quite a personal tone as he relates his struggle with unjust imprisonment by a regime whose hallmark was ‘a mix of the needlessly brutal, the petty, and the incompetent’. This personal story is also mixed with politics, for Turnell has an insider’s view of Myanmar’s ongoing struggle for freedom, one of the great dramas of modern Asian history.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

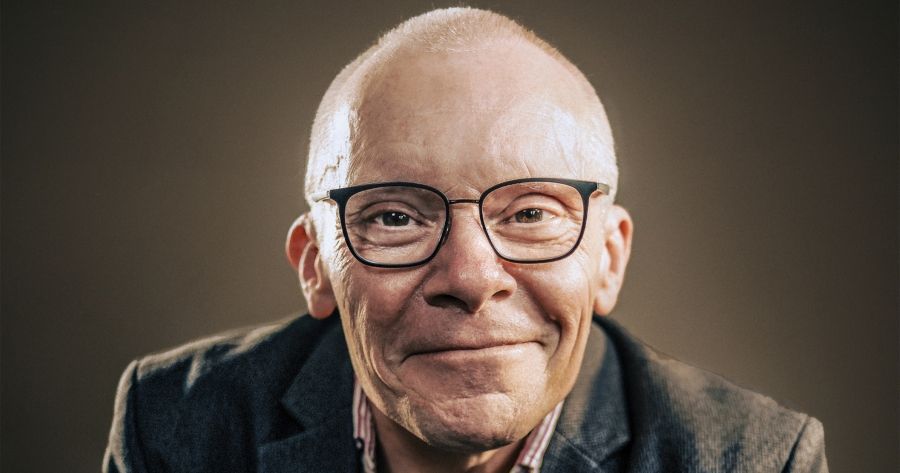

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Nick Hordern reviews ‘An Unlikely Prisoner’ by Sean Turnell

- Book 1 Title: An Unlikely Prisoner

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $35 pb, 300 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Turnell is circumspect in his assessment of the NLD’s time in government. He gives it credit for laying the groundwork for the reform of Myanmar’s economy, among other things. But he makes only the slightest allusion to the military’s genocidal campaign, which began in 2016, against the Rohingya people of northwestern Myanmar, and none at all to Daw Suu’s defence of that campaign, including before the International Court of Justice.

The prison conditions Turnell endured were extremely harsh. He himself was physically maltreated. He knew of other prisoners who had been tortured. One, a great friend who stood up to the guards on Turnell’s behalf, was later beaten to death. Initially held in Yangon, Turnell was kept in ‘The Box’: a room within a room where the lights stayed on round the clock (except when the power failed, invariably in daytime). Moved to another jail in the new capital of Naypyitaw to face trial, he discovered that his fellow prisoners there were friends and colleagues from the deposed NLD government, including Daw Suu. Among them were his co-accused in his trial, a process Turnell describes as ‘Kafkaesque’. For example, he was charged under Myanmar’s Official Secrets Act, even though, as a foreigner, he wasn’t actually subject to it.

Turnell is frank about the difficulty he had in coping with his sense of isolation and powerlessness. He had a tenuous line of communication to the outside world, to his family, and to Australian and other foreign diplomats, but even so he confesses to having occasionally ‘lost it’. There was, however, one thing which ‘more than anything kept me going’: books.

He read whatever he could get his hands on, and mentions more than thirty authors across a range of genres: biography (Alexander Hamilton, John Maynard Keynes), history (Robert Hughes’s The Fatal Shore, Noel Mostert’s The Line upon a Wind), modern fiction (Julian Barnes, Ian McEwan), children’s literature (Enid Blyton), and The Lord of the Rings. He and Daw Suu shared a particular enthusiasm for Tolkien.

Turnell didn’t just read to escape from his predicament, he read to engage with it as well. He steeped himself in the literature of imprisonment, including that ‘seminal work of freedom’, 1984 (George Orwell, he notes, has a particular following among the Myanmar opposition). He rekindled his enthusiasm for the prisoner of war stories, such as Paul Brickhill’s The Great Escape and Pierre Boulle’s The Bridge on the River Kwai, which were standard fare for young Australian men of his vintage. These raised the question for Turnell as to whether he should be trying to defy his captors – something he dismissed as impractical.

During his imprisonment, Turnell’s view of the political struggle in Myanmar was, by definition, limited to what he could see and hear from his jail cell: that is, the junta’s suppression of the NLD by brute force. One might infer from this that the generals will hang on to power indefinitely, but this is not necessarily the case. Both the junta and the NLD leadership belong to Myanmar’s majority Bamar ethnic group, but the conflict between them is only one element in the country’s unfolding political dynamic. The other is the relationship between the Bamar and Myanmar’s many other nationalities – including the Shan, Karen, Rakhine, and Mon – whose homelands lie along the country’s borders. Beginning in late October 2023, armies aligned with these ethnic groups inflicted a string of military reversals on the army, reversals which have substantially weakened the regime. As a result, there is a real prospect that the junta might, if not be overthrown, then at least have its authority largely restricted to the central part of the country.

At the recent Lowy Institute launch of An Unlikely Prisoner, Turnell described these developments as ‘hopeful’, while tempering his comment by pointing out that the struggle against the junta had been going on for decades. Even so, it’s not beyond the bounds of possibility that Turnell may one day again be asked to put his expertise at the service of Myanmar’s people.

Comments powered by CComment