- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Something like jasmine

- Article Subtitle: A sweeping tale of thwarted love

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The potential for Australian literature to address the history of colonised people in this country and elsewhere is of great consequence. New perspectives not only rewrite history to include ‘herstory’, but also reconsider what we believe and broaden our view of ourselves as active contributors to our collective and individual past. A spate of recent books has attempted to do this: Anita Heiss’s Bila Yarrudhanggalangdhuray: River of Dreams (2021) and Geraldine Brooks’s Horse (2022) are two that come to mind.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Christopher Raja reviews ‘Sunbirds’ by Mirandi Riwoe

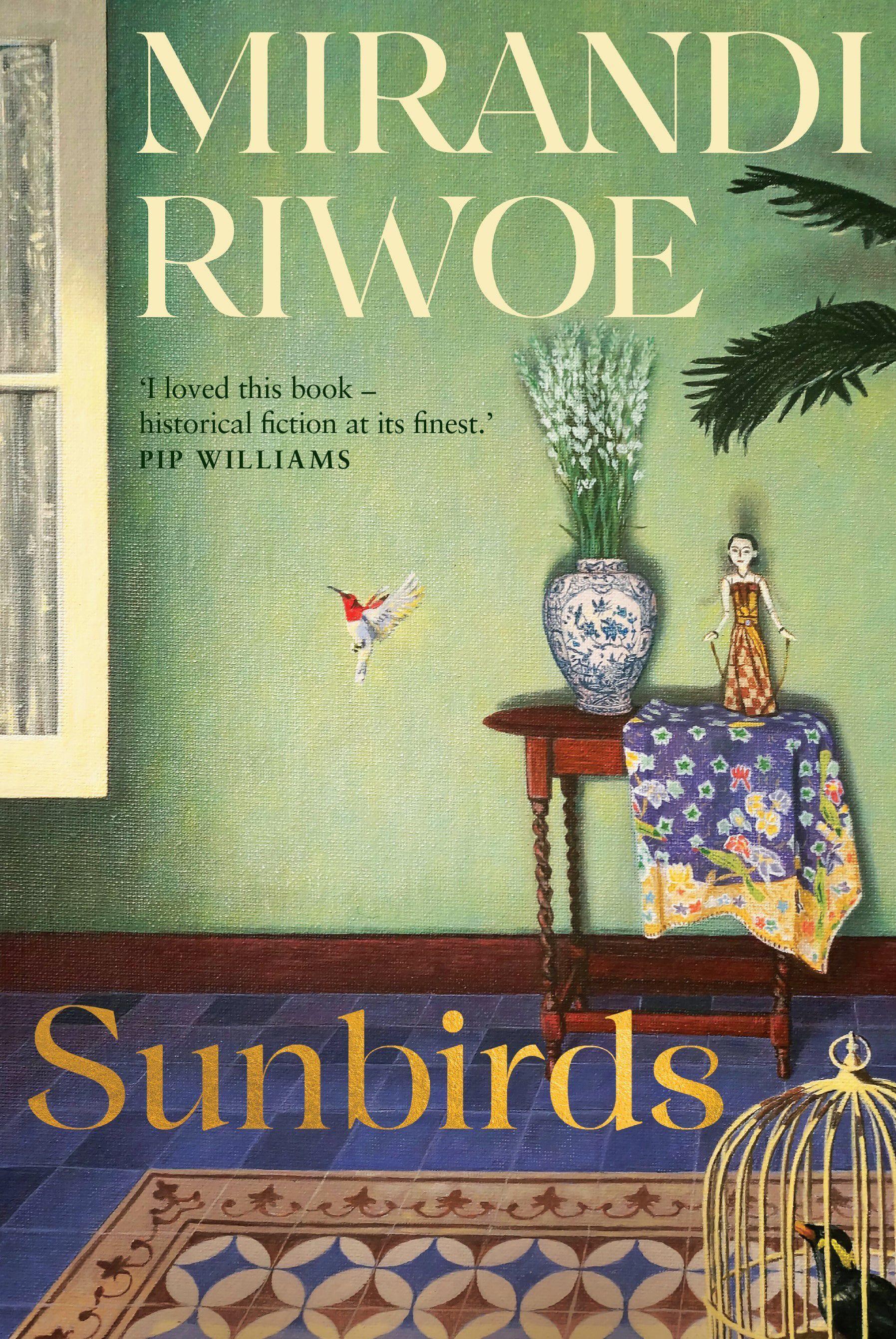

- Book 1 Title: Sunbirds

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $32.99 pb, 312 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Sunbirds begins with a breakneck prologue. We are on the Indian Ocean, on 3 March 1942. Mvr Huisman, Mevrouw van Oudijck, Eva, an unnamed infant, seven servicemen, two student pilots, and the pilot have been shot down by Japanese fighter planes. Languishing in Roebuck Bay, Mvr Huisman, ‘scans the bay, taking in the riddled, lopsided seaplanes, the burning crafts, the distant specks drifting on the water – bird, human or wreckage, she can’t be sure’. She thinks of Mattijs, unsure if he is piloting a flight out of Bandoeng or whether he will be waiting for her in Broome. They have had some sort of union. At death’s frightening door, young Mvr Huisman also thinks about a suitcase and the cook, Kokie, she was forced to leave behind.

The timeline shifts. In Chapter One, we are in Java. It is December 1941 and we meet Mattijs, a ‘diamond ring nestled in his coat pocket’. Riwoe deals with the love story in a surprising fashion (no spoilers). Mattijs is staying with the van Hoorns at their ‘famous’ tea plantation, Serehwangi, surrounded by firecrackers that singe the tips of ‘nut grass’, the scorched leaves of the kamari tree, the bushy tjamara trees. The writing is rich and sensuous. Riwoe is skilful at conveying scents and sounds –

‘a whiff of something like jasmine’, the ‘heavy scent of stale perfume, cigar smoke, hair oil’, the sound of a jazz band, the other guests who ‘have travelled for hours by car, carriage or horseback to attend their famous Sinterklaas party’. At times, her writing reminds me of W. Somerset Maugham and Michelle de Kretser.

With its crackling prose – ‘a crackle of fireworks brings Mattijs back to the party’, ‘the newsreader’s voice crackle’– its cinematic set-up, and its vivid, evocative details, Sunbirds both irked and impressed me. It races forward. We meet various colourful characters, including Diah the housekeeper, her provocative, handsome, freedom fighter brother Sigit, and the seamstress, Ibu Rahma’s daughter, Endah (aka Fientje). The structure of the novel is then upended and we are introduced to a novelette, each section of which begins in the first person, from the point of view of tragic Fientje de Vries, the ‘mixed-blood’ Endah, who is found in a Chinese cemetery in Bandoeng; but then it reverts to the third person. This is where the novel begins to lose momentum.

At a quick pace and with a wealth of detail, Riwoe uses the imaginative elements of fiction to convey her rousing account of the lead-up to the Japanese invasion of the Dutch East Indies in 1941 as the van Horne family throw a Sinterklaas party at their tea plantation in Java. Then it hurtles forward to tell an epic story involving a dead prostitute who is given a voice, freedom fighters, and a plane crash, and jumps all the way to Sydney and back to Puncak, 1992.

This is an entertaining book, but writing historical fiction well is not easy. Writing dialogue that doesn’t sound clichéd or stilted is a challenge; at times Riwoe misses the mark, and the book reads more like a Hollywood movie script. ‘I don’t think we are going to make it, Mvr Huisman?’, Mvr van Oudijck yells as the seaplane dips, before the pilot pulls her right again (echoes of Harrison Ford). It’s hard getting the dialogue to ring true. Here’s another trite snippet: ‘I’ve heard the Japanese are locking up all the Europeans.’

Sunbirds, nonetheless, is inventive, and she engages with colonialism, class, sexism, migration, and their reverberations. Intriguing are her abiding themes: love, loyalty, violence against women, war and imperialism. She draws profitably on her own background. Her ‘Indo’ protagonist, Anna, wonders whether a female singer in Batavia has ‘Chinese blood, like her own’, although the singer’s skin is ‘milkier’.

Despite my misgivings about the structure, Sunbirds is a sweeping tale of thwarted love that I found moving in a way that reminded me of Love in the Time of Cholera. This novel will strike the right chord for many readers, especially those who like to indulge in bittersweet romance in their fiction.

Comments powered by CComment