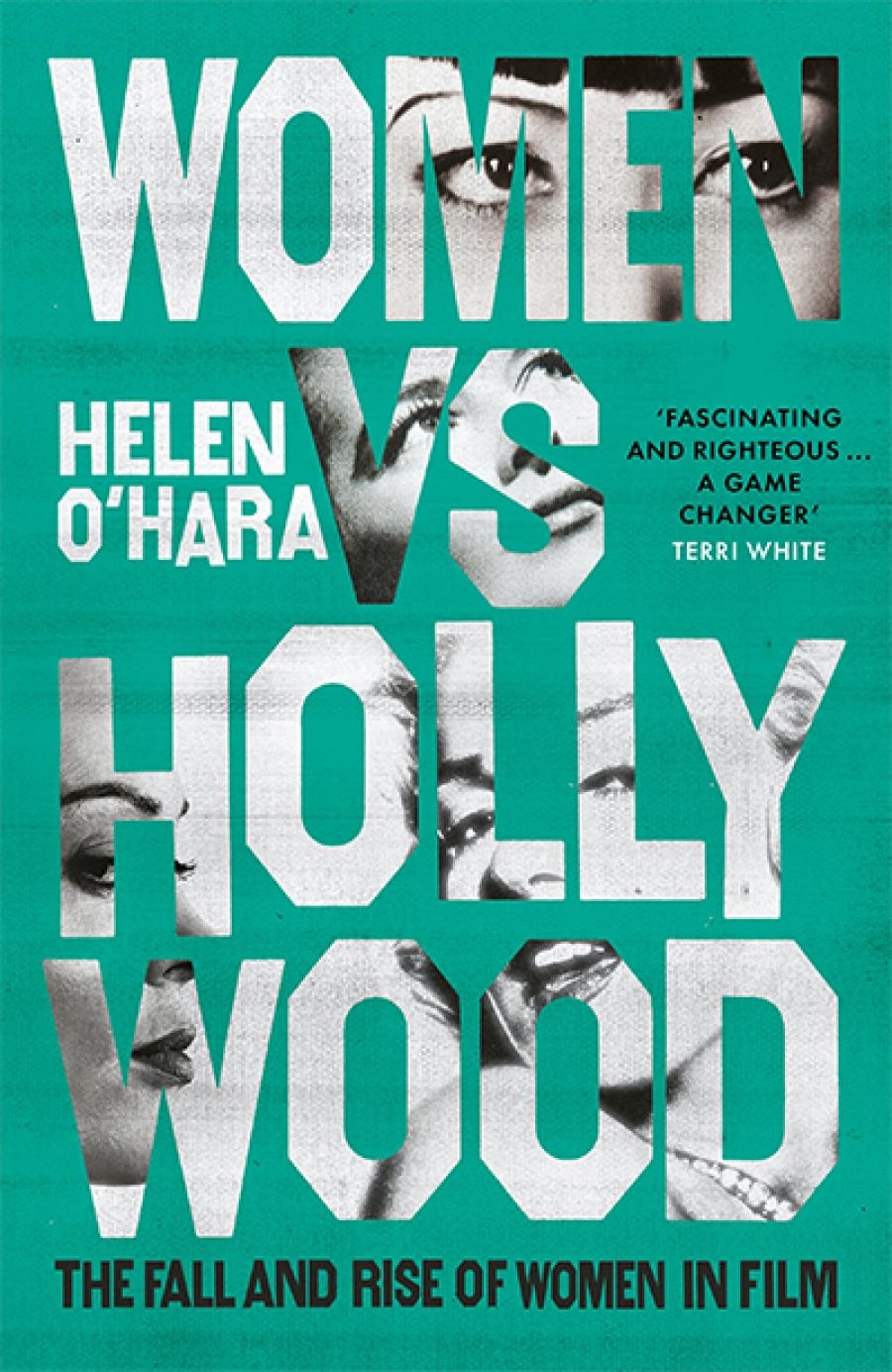

Unanimal, Counterfeit, Scurrilous by Mark Anthony Cayanan

Giramondo Publishing, $24 pb, 102 pp

Few books blur the line between beauty and ugliness more than Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice (1912). The novella follows the ageing writer Aschenbach, whose absurd over-refinement – born in part of repressed homosexuality – is dismantled by Tadzio, a beautiful boy he encounters on holiday in Venice. His obsession with Tadzio represents the displacement of mortality (Aschenbach will soon succumb to cholera) through a wilful surrender to decadence and decay.

Unanimal, Counterfeit, Scurrilous, a polyphonic suite of verse from Filipino poet Mark Anthony Cayanan, claims to ‘loosely [channel] the dynamic of desire and inhibition’ in Mann’s novella. In fact, it does something quite different. It is written in the ‘fourth person’, an ill-defined chorus of voices marked by tenuous fluidity of self. Protean identities – unfixed and ‘unfinishable’ – respond to and resist Aschenbach’s repression and rigidity, against a drastically different moral and political backdrop. The interior monologues alternate between two modes: prose poems written ‘as Aschenbach’ that border on literary criticism, and others adapting the book’s theme through a contemporary queer lens and with oblique reference to the current political situation in the Philippines.

Familiarity with Mann isn’t essential but will help readers to appreciate Cayanan’s insights. They are particularly astute on Aschenbach’s self-dramatising tendencies: ‘scenarios of unsanctioned passion are swaths of an inner life repurposed from bourgeois melodrama’. ‘There’s no knowing now,’ begins another poem; ‘knowing dignity’s no longer a reason to keep alive a life that precludes abandon’.

Cayanan’s lexicon is unabashedly rococo, the syntax syncopated. The voices that emerge are uncanny, breathless, enfolded in an ironised, swirling grandeur characteristic of Mann, as in this almost parodic homage:

Tadzio, you’re the tired gold of sunset, of ardour and unused heat, of horses drowning in the sea. There’s tulle over the lampshade, tulle of the landscape, Tadzio. Mine, mine, the white word admonishes the world.

Cayanan counterbalances Aschenbach’s ‘queer tragedy’ with vignettes of modern travel and life on the Filipino streets. These prevent the book’s exploration of selfhood from becoming too insular or claustrophobic, and add a postcolonial layer to the commentary. Once Aschenbach’s demise has been charted, though, Cayanan breaks decisively into a confessional, autobiographical mode that risks working too far against Aschenbach’s agonised dissimulation. ‘I enable my self-absorption,’ the speaker writes. ‘I’m silly enough to think it makes me interesting.’

Some of the commentary can feel too glib: ‘Mann offloads his gay shame onto his characters’, for one. Even so, the final shift towards candour helps to resolve some tensions in Unanimal, Counterfeit, Scurrilous – not so much a ‘queer tragedy’ as a complex reworking of Death in Venice that leaves readers to ponder the new challenges and anxieties of modern queer life.

Errant Night by Jerzy Beaumont

Recent Work Press, $19.95 pb, 78 pp

Science fiction tropes have found their way into much poetry over the last ten years – from Tracy K. Smith’s Life on Mars (2011) to J.O. Morgan’s The Martian’s Regress (2020) – but none is quite as left field as Jerzy Beaumont’s Errant Night, a verse story that uses interstellar travel as a semi-allegory for grief.

In the midst of a Canberra winter, the speaker begins by declaring that ‘depression is [his] heart’s armour. Rusted shut,’ and follows this with the metaphor of constellations disappearing in the night sky. The speaker then takes off in his spaceship (‘built from schematics found on Reddit’) to find the missing stars. Flying over the capital, he collects ‘neon halos from street lights, fast food signs’, but these artificial stars are no substitute for the real thing. ‘I won’t be back,’ he writes, ‘until the night sky is flooded with light.’

It is a simple – almost pat – metaphor, but it is elaborated with the intricate world-building of a fantasy novel. With a sound dramatic hand, Beaumont describes his travails on Narcissau, a port city or ‘Cubist favela’ he finds after being made ‘homeless in space’.

The work’s reliance on sci-fi tropes can seem to obfuscate the realities of grief as much as illuminate them. Certainly, you are left with the feeling that Beaumont might have a lot more to say about his own experiences, but there are also moments when the truth breaks through the grand metaphor. ‘It has been fifty-four days since you died. I think about you a lot. Wonder how many stars count your absence at night. Some things can’t be fixed.’

At the end, the speaker admits: ‘I never did find the stars, but I don’t mind.’

Errant Night presents readers with narrative poetry that is both epic and fugue. Some of the set pieces are as muddled as the processes of grief itself, but Jerzy Beaumont does in fact find a few stars. ‘It is not the avoidance of pain that will save me,’ he writes, ‘but the dedication to repair.’ This is a poet recuperating and slowly emerging. We owe him our attention and patience.

I Said the Sea Was Folded: Love poems by Erik Jensen

Black Inc., $22.90 pb, 81 pp)

Meanwhile, I Said the Sea was Folded: Love poems – the début collection of Erik Jensen, co-founder of The Saturday Paper and editor-in-chief of Schwartz Media – is presented, like Cayanan’s work, as an exploration of queer experience.

It is easy to imagine how someone in love could write the sort of guileless sweet nothings in this book (the poems are addressed to Jensen’s partner Evelyn Ida Morris), but much harder to imagine how they could ever have been published.

Jensen’s verse is woefully slight. It aims for gnomic profundity but tumbles into the mundane or mawkish every time. To say these snippets are like refined Instagram poems would insult the Rupi Kaurs of the world, who look like the height of emotional sophistication alongside Jensen. Here is ‘Second time’ in its entirety:

My favourite line

Is when you said

You were dreading

More chicken soup.

Later you asked

If it was Wednesday

When you made it

And whether it was still

Okay to eat.

That is about as exciting as a shopping list. The poet seems to suffer from a journalist’s addiction to reportage. Such seismic personal events as making meatballs or ordering ‘milled beetroot / with a brick of cabbage’ at a restaurant are relayed with a plodding, dutiful accuracy. The result is dullness of the kind the poet himself tries to justify as a poetics of inarticulacy: ‘I don’t know if you read poetry,’ begins ‘Last Tuesday’; ‘I don’t know if I write it.’

Readers will know instantly. What is most striking is how few of these poems communicate anything meaningful about Ida Morris. The poem ‘Waiting’, which includes a lone note of poignancy (‘You say your childhood was purple feet / Made cold by the river’), is one of the few. Most of the others lose focus quickly, veering into ramblings such as that in ‘Glasses’:

This morning

You were smiling

And I wondered what

You could see

Without your glasses.

I just remembered

That last night

In my dreams

I wrestled an alligator.

No doubt this has some private significance, but the whole book is like this. It does not translate into anything of artistic value for the general reader.