- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘I don’t hold a hose, mate’

- Article Subtitle: The luck and swagger of Scott Morrison

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Flash back to that election night in May 2019, when Australians, depending on their party affiliation, were either overjoyed or appalled at the Coalition’s return despite the opinion polls. That evening, Scott Morrison – a man little known to Australians until assuming the prime ministership just nine months before after an ugly leadership coup – summed up Coalition sentiment and his own Christian faith: ‘I have always believed in miracles,’ Morrison said, before asking, rhetorically, ‘How good is Australia?’

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Prime Minister Scott Morrison in meeting in Canberra on September 2020 (Nareshkumar Shaganti/Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Prime Minister Scott Morrison in meeting in Canberra on September 2020 (Nareshkumar Shaganti/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

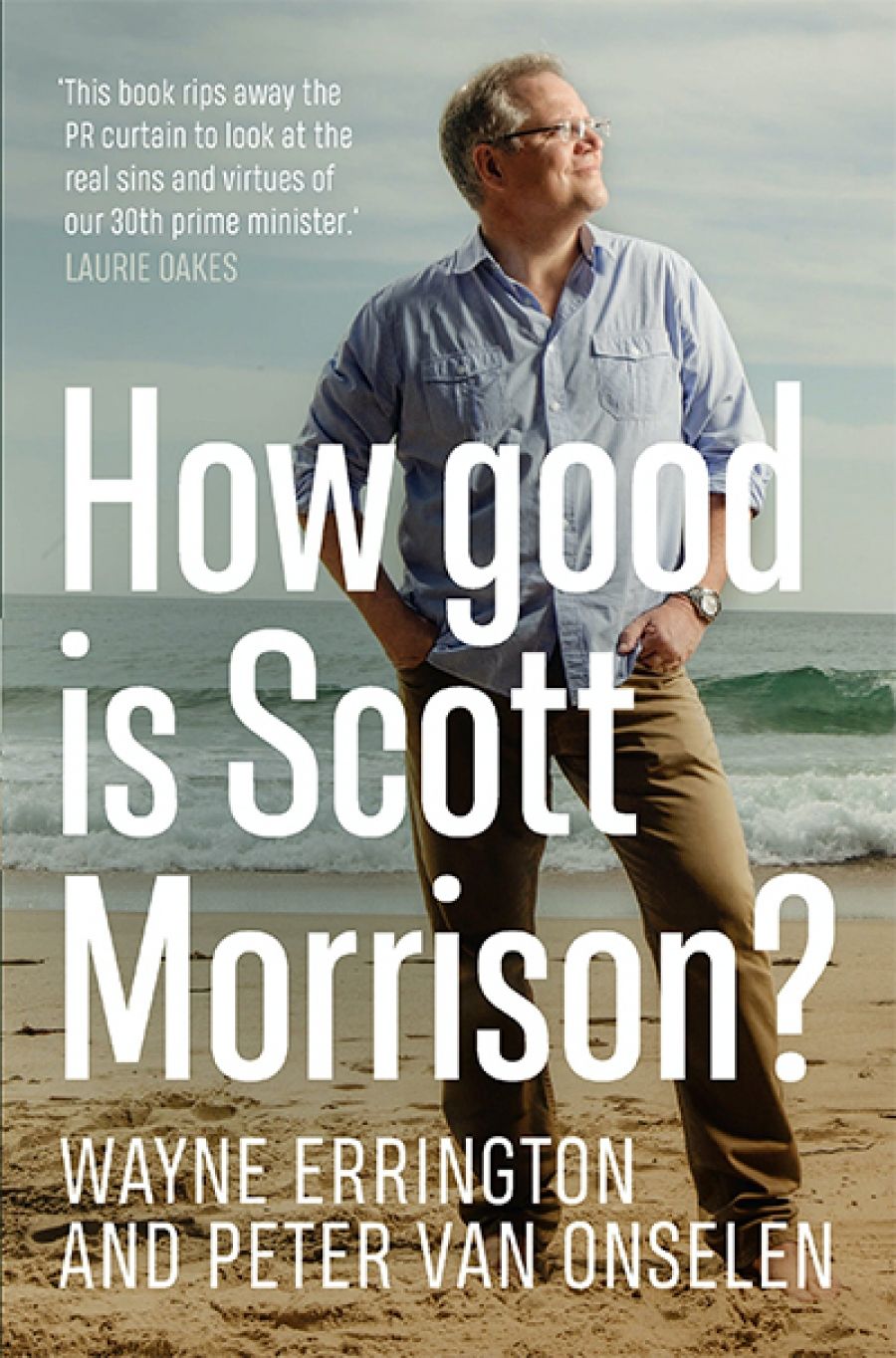

- Book 1 Title: How Good Is Scott Morrison?

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette, $34.99 pb, 329 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/BX5O3J

Wayne Errington and Peter van Onselen pose that same question, literally: how good is the man many believe to be the most image-driven prime minister in Australian history? Just what will be Morrison’s legacy? Their answer, threaded with jaw-dropping ‘insider’ detail across fourteen chapters, is an often harsh, even scathing, account of Morrison as a leader obsessed with style rather than substance, activity rather than achievement. We see evidence of ‘ScoMo’ as a manufactured entity produced from a cynical marketing recipe. Open a packet of ‘faux-masculine’ blokeyness, add a generous helping of ‘daggy dad’, mix in some family references, and top it off with curry cooking, pool playing, and beer drinking. Best served in rolled-up sleeves in regional Queensland.

The real Scott Morrison is far from the knockabout ‘ScoMo’ regional and blue-collar Australia came to love in 2019. Yet how does one sell a wealthy marketing executive who practises a religion shared by one per cent of Australians and lives in a wealthy Sydney suburb? It’s not easy. That’s why, the authors argue, Morrison remains ‘Scotty from marketing’, a man who has dedicated his professional and political life to image-making.

Critically, that argument does not subtract from Morrison’s admirable ambition and work ethic, which saw him climb the greasy Canberra pole in just eleven years (he was elected to parliament in 2007). Nor does it ignore the political antennae – often on point, too often not – that allow him to seduce a cynical electorate with an ‘ordinary Australian’ persona while wedging a hapless Labor opposition.

Book-length accounts of current political events and actors are now the norm. As a genre of long-form journalism, such ‘insider’ accounts are essential so that ‘outsider’ audiences, often lost in the fog of political ‘spin’, can make sense of their politics. But strictly journalistic accounts, without the buttress of theoretical context, suffer short shelf lives. Errington and van Onselen, authors of a number of books on Australian politics and leaders, have avoided this pitfall by offering up not just a forensic account of Morrison’s operational leadership as prime minister but, importantly, a remarkably accessible study of leadership, together with a useful discussion of an evolving Australian federalism reinvented by the forces of Covid-19. Who would have thought the states could exercise Commonwealth quarantine powers so effectively? The result is a first-rate book, written in breezy prose punctuated with the odd profanity, that unpacks Morrison’s place in Australian politics.

The authors’ key theme is that Morrison has scored too few prime ministerial runs when it mattered. Obsessed with the short-term superficialities of politics, Morrison risks becoming another Malcolm Fraser: a Liberal prime minister endowed with a mandate who sat on his hands and achieved little. It’s a difficult proposition to refute: ask anyone what Morrison has achieved in his three years as prime minister and she is likely to mention only winning an unwinnable election and managing the pandemic.

To be sure, capping Australia’s Covid infections at below 0.02 per cent of the global total was a remarkable feat, even if state premiers must share the credit. But prime ministers are only as good as their last election, and voters’ appreciation of crisis management evaporates quickly. Look no further than the 2010 federal election: little gratitude was extended to Labor despite Kevin Rudd’s generous stimulus packages – pilloried by the Liberals at the time – which saved Australia from recession during the Global Financial Crisis. As slow vaccination rollouts, long-term unemployment, and record debt and deficits hit home, the fact Australia did not become another United States or India will hardly be enough.

That’s why a key strength of this book is the attendant discussion of leadership theory. ‘Leadership matters,’ the authors argue – even in big-ticket policy elections like the GST in 1998 or Labor’s tax reforms in 2019. ‘You vote for me and you get me,’ Morrison crowed during the 2019 campaign. ‘You vote for Bill Shorten and you get Bill Shorten.’ Yes, leadership matters very much.

If success pivots on leadership, it might be tempting to cut Morrison some slack: the man was new to the job when the 2019 bushfires erupted, and those flames were barely extinguished by the time Covid reached Australia. But Errington and van Onselen argue that Morrison must assume at least some responsibility for the public-relations quagmire in which he so often finds himself.

One failing is obvious: Morrison’s transactional style, PR-dependent even by modern standards, is insufficient for great leadership. Of course, all political leaders engage in the politics of transaction – pandering for votes, negotiating with stakeholders, trading party preferences – but Morrison to date has given no hint of the transformational leadership characteristic of impressive leaders. There has been no inkling of a long-term vision for Australia, only short-term budget sweeteners to court enough voters to win the next election. Even the establishment of the National Cabinet – the one genuinely meaningful federalist reform likely to outlive the Morrison government – was ultimately transactional. Locked into the cabinet convention of confidentiality and public unity, state premiers are honour-bound not to undermine the prime minister. It’s clever politics but hardly nation-building.

Critically, the authors remind us that Morrison’s transactional politics mirror his own chameleon-like persona. When he first ran for Liberal pre-selection for the Sydney seat of Cook in 2007, Morrison emerged as the compromise candidate wedged between two factions. It would be a tactic repeated during the Liberals’ 2018 leadership spill, when Morrison was seen as a compromise between Peter Dutton on the hard right and Julie Bishop on the left. Entering the House of Representatives in 2007 under moderates Brendan Nelson and, later, Malcolm Turnbull, Morrison was ostensibly a moderate. Promoted by Prime Minister Tony Abbott to Minister for Immigration and Border Protection, Morrison became an abashed conservative.

Ultimately, the authors contend, Morrison is a pragmatist like his ideological godfather, John Howard. Morrison, like Howard, won’t die in an electoral ditch on principle. If an interventionist economic approach – JobKeeper payments, a Keynesian budget – is what separates victory from defeat, so be it. Perhaps that’s why neoliberals have become so thin on the ground inside the Coalition.

Even here, Errington and van Onselen demonstrate that Morrison is a better Liberal Party tactician (he was a director of the New South Wales branch) than traditional retail politicians like Howard. In short, Morrison had a plan to become prime minister, but not a plan once there. Nowhere was the man’s ill-preparedness for the depth of the job – the emotional intelligence required to be the nation’s leader – writ larger than in his mishandling of his first major test: the 2019–20 bushfires that claimed thirty-three lives and destroyed twenty-four million hectares. Holidaying in Hawaii, Morrison petulantly replied to calls for his early return with ‘I don’t hold a hose, mate’. His subsequent visit to burnt-out southern New South Wales looked contrived – just another PR stunt – especially when forcibly grabbing reluctant hands to shake. Yet Morrison has learnt from some (though not all) of those mistakes, and he has undoubtedly grown into the job during the pandemic.

Those events exposed another, darker side of Morrison: an easy willingness to avoid responsibility and to shift blame to others. Where is the contrition for the $1.2 billion Robodebt fiasco (designed under Morrison as Social Services minister), or the bungled water-buyback scheme? Where is the responsibility for the off-loading of the Ruby Princess, for his attacks on former Australia Post CEO Christine Holgate, for the ‘sports rorts’ saga, for the tolerance shown MPs Craig Kelly and Andrew Laming? Indeed, when cornered, Morrison eschews the mea culpa and instead doubles down. Criticism is just chatter from ‘inside the Canberra bubble’, he says. The fact that Morrison buys into that sort of cheap populism also blots his legacy, as does his relationship with Donald Trump and his failure to condemn the outgoing president for the January riots.

It’s this surliness, the authors argue, that sees Morrison go after perceived enemies. Consequently, funding cuts to the ABC, to the Australian National Audit Office, and to universities simply look petulant. Moreover, when Covid first appeared, Morrison reassured us we’re all in this together. Before long, Victoria was castigated for its second wave, with Queensland and Western Australia – all Labor states – condemned for border closures. The New South Wales response, however, was described as ‘gold standard’.

Wayne Errington and Peter van Onselen conclude that Morrison is still likely to win the next election. But had their book been scheduled for a couple of months later, enabling them to consider Brittany Higgins’s allegations, the Christian Porter saga, Holgate’s very public accusations, the behaviour of Craig Kelly and Andrew Laming, and, of course, what appears to be a bungled Covid vaccination process, their conclusion might have been very different.

Comments powered by CComment