- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Selected Writing

- Review Article: Yes

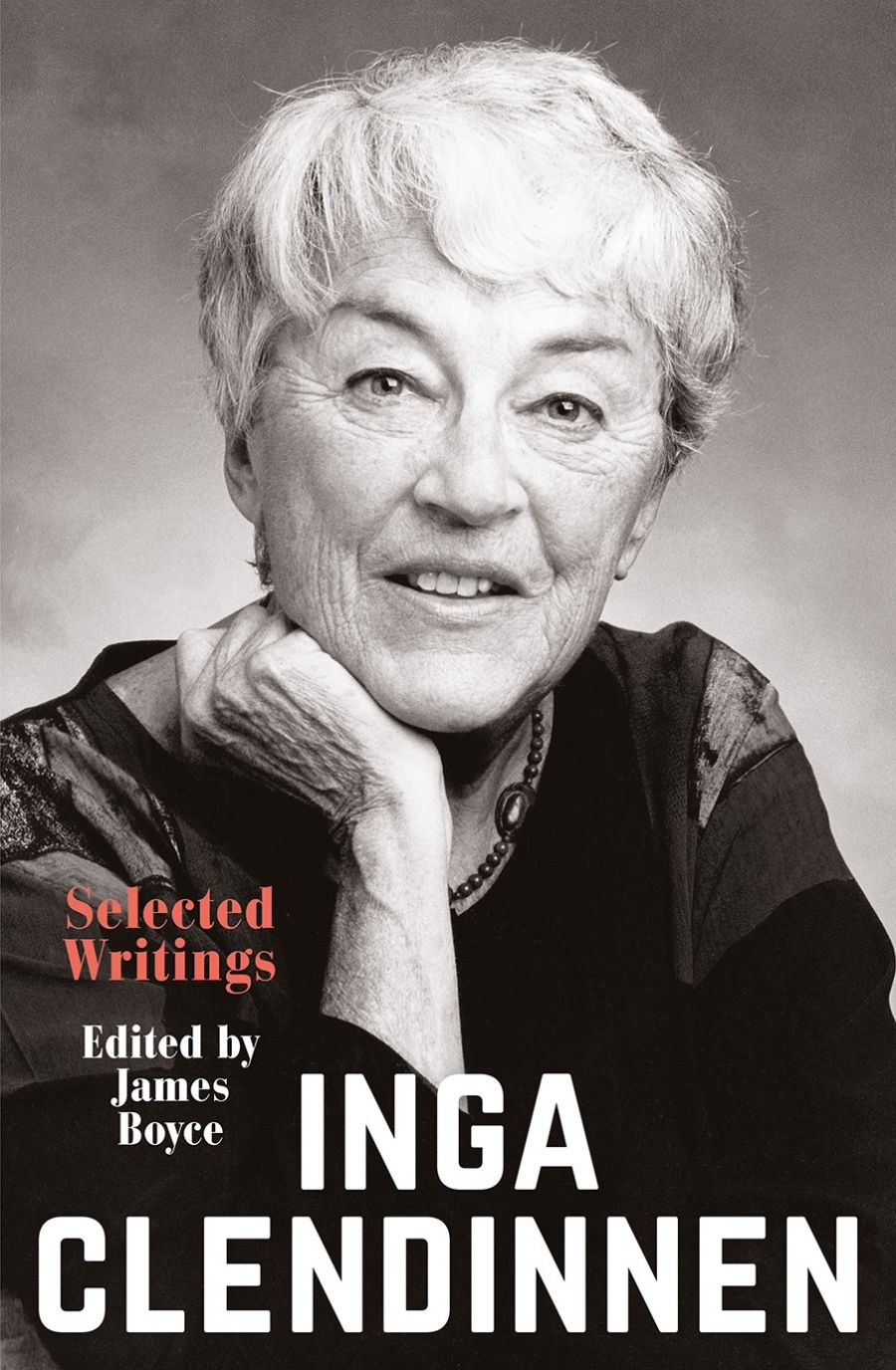

- Article Title: A pen on fire

- Article Subtitle: The enduring appeal of Inga Clendinnen

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It is wonderful to immerse oneself for days in the precise, elegant, passionate words of historian Inga Clendinnen (1934–2016), as this welcome collection of her writings enables one to do. Clendinnen’s distinctive voice comes through: warm, confidential, witty, and driven by a fierce intelligence. All her major writings are here – essays, articles, lectures, memoirs, and extracts from her books – deftly selected by James Boyce, a historian thirty years younger than Clendinnen and himself a highly original thinker and writer. As Boyce observes in his perceptive introduction, ‘Clendinnen’s subject was nothing less than human consciousness.’

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Inga Clendinnen

- Book 1 Subtitle: Selected writing

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $32.99 pb, 400 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/gbRqKg

Clendinnen constantly reminded her readers that the point of history – indeed any humanistic scholarship – is to expand and strengthen our moral imagination so that we may transcend our own identity, time, and place, and understand the experience of others. Through this process, she argued, history is conducive to civic virtue. Clendinnen took up this theme – ‘the practical usefulness of good history both morally and politically’ – in her 1999 Boyer Lectures, with which this collection begins. In 1999 she stated, ‘while I am a historian and an Australian, I am not an Australian historian’. But that was already changing, for illness had catapulted Clendinnen into ‘curing her ignorance’ of home. This book helps chart her remarkable career from devoted teacher, academic, and renowned scholar of Mesoamerican history to memoirist, public intellectual, internationally acclaimed author, and, finally, distinguished historian of her own country.

Clendinnen did not learn to read until she was eight, but she went on to become a famous reader. ‘Reading’ was her scholarly technique and appeared in the title of two of her most celebrated writings: Reading the Holocaust (1998) and ‘Reading Mr Robinson’ (about George Augustus Robinson, Chief Protector of the Aborigines for Port Phillip District, an essay first published in ABR in 1995). When Clendinnen finally got the knack of reading as a child, she couldn’t believe it was legal, so subversive did it seem. Reading set her free, and in every treasured book she found ‘a voice ready and eager to talk to me’. At university she ‘wallowed in the joys of promiscuous reading’. Her teaching style was to read intensively alongside her students, endlessly discussing insights. She never got over the wonder of reading: ‘this uncarnal, intense-to-incandescent yet always accessible intimacy has no parallel in the social world, and once enjoyed it is impossible to live without’.

She came to writing late, too. Her first published article appeared when she was forty-five, and then in the next thirty years wonderful books and essays flowed from a pen on fire. Her historical vision was thus born with full confidence and maturity. She found her writing voice from her experience of teaching, for she imagined her students as her audience and journeyed companionably with them into the past, reading the evidence together. For her, ‘the core narrative was always the process of inquiry’.

At the beginning of the 1990s, Clendinnen was hijacked by serious illness. As she lay in a noisy shared hospital ward waiting for a liver transplant, her writing became a desperate means of escape and survival, a kind of ‘private therapy’. From that traumatic transformation, she unfolded herself from a chrysalis into a new state of being. Strangely liberated by her illness and the blessed renewal of the transplant, Clendinnen wrote herself back into vigorous scholarship and citizenship. She delved inquisitively into her own life and the life of her country.

There are five sections in this collection: Encounters in Australia, Mesoamerican explorations, Facing Gorgon (the Holocaust), On History and Writing, and On Life (and illness). The collection begins by taking us into the heart of Clendinnen’s later Australian work and then backtracks to her earliest scholarship. If you chiefly know Clendinnen through her Boyer Lectures, her reflections on the Holocaust, or her explorations of Australian history, you will be entranced to hear her familiar voice introducing you to the Aztec and Mayan worlds of the sixteenth century.

Here you will find her brilliant description of the imperial city of Tenochtitlan as the Spaniards first saw it in 1519, a magnificent marvel, the greatest city in Mesoamerica and Europe, a prize to be secured for their king. In the longest piece in this collection – a 1991 article for the academic journal Representations on ‘Cortés and the Conquest of Mexico’ – Clendinnen offers a rich analysis of the ‘first great paradigm for European encounters with an organised native state’. She reveals the grip of racism and hubris on generations of written history and shows how historians have often been ‘the camp followers of the imperialists’. She then teases out the complexities of the protracted warfare between the Spanish and the Aztecs in an enthralling series of narratives. Clendinnen’s ethnographic eye, her ‘double vision’ of looking into and through the sources, and her humility in the face of mystery enable her to discover new layers of the past. She portrays the uneasy protocols of battle and sacrifice, the seemingly incomprehensible refusal of the Aztecs to accept defeat, and the startlingly different cultural conceptions of nature, animals, space, time, honour, and fate that became, as much as technology and disease, decisive in this momentous conflict. Finally, there was the awful irony that the ‘victors’, in winning the jewel of Tenochtitlan for their king, completely destroyed it.

Clendinnen’s reading of the ritualised, violent encounters between the Aztec leader Moctezuma and the Spanish conquistador Cortés is echoed in her later famous analysis of the spearing of Governor Phillip at Manly Cove on 7 September 1790, which is also reproduced in this collection. Such are the rewards of reading Clendinnen’s writings on the Maya and the Aztecs alongside her other work. There are also clear correspondences between her studies of the Aztec Empire’s confronting culture of human sacrifice and her reflections on the horrors of the Holocaust. Clendinnen constantly fought against the sickening of curiosity and imagination in the face of bureaucratic brutality and systematic murder. Empathy and intuition failed her as a means of accessing such past experiences. To find a way forward, she introduced the legend of the Gorgon.

A Gorgon was a terrible creature of ancient Greek mythology whose glance turned everything to stone. Perseus was able to slay the Gorgon Medusa by holding her reflection in his polished shield and cutting off her head. Clendinnen believed, ‘If we are to see the Gorgon sufficiently steadily to destroy it, we cannot afford to be blinded by reverence or abashed into silence or deflected into a search for reassuring myths.’ So the question she posed was this: what kind of steady, systematic scrutiny, what kind of moral intelligence, might enable us to hold this terrible thing in our contemplation? Her answer was the craft of history.

Has anyone celebrated the historical method so well? Through powerful storytelling, forensic analysis of episodes, and her lovable companionship in ‘the secret society of readers’, Clendinnen inducts us in the wonders of historical thinking. She reveres historians as ‘magicians’, and tutors our sense of awe at the ‘secular resurrections’ they can conjure. She invokes a past that is powerful and ever-present: ‘its hand is on our shoulder’.

Boyce reminds us that Clendinnen was a member of the celebrated ‘Melbourne Group’ of historians that came into being at La Trobe University in the 1970s and included Greg Dening, Donna Merwick, Rhys Isaac, June Philipp, and Tony Barta. They pioneered approaches to ethnographic history and took on the challenge of integrating anthropology and history by attending especially to cross-cultural encounters and episodes. In remembering Clendinnen, we honour also the work of these friends and colleagues and the inspiration they gave a generation of Australian historians.

The collection ends with Clendinnen’s later writings on illness and memory. In the netherworld of the hospital, Clendinnen’s researched pasts began to interlace with her own. The deities (‘monsters of caprice’) who held sway over the Aztecs of Mexico now seemed to have her in their grip. The gruesome Aztec theatre of excising a living, beating heart from the body of a warrior became weirdly inverted in her own experience of having a living organ from a dying body installed in hers. She wrote about this paradox in her memoir Tiger’s Eye (2000) and also in an article for the Australasian Journal of Psychotherapy, which, rather wonderfully, has been included in this collection. Clendinnen happily presented herself to the psychological profession as ‘a talking document’.

Clendinnen loved the way literacy connects ‘the living with the living, but also with the great company of the dead’. She cherished her friend Michel de Montaigne, who died more than four hundred years ago but who ‘is still alive to me’. She saw her art as achieving a kind of triumph over death, as denying the immutability of time. James Boyce’s selection has been made with such insight and sympathy that it produces what feels almost like a new book of Inga Clendinnen’s, a secular resurrection of its own.

Comments powered by CComment