- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Calibre Prize

- Custom Article Title: 2014 Calibre Prize (Winner): Unearthing the Past

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Christine Piper is the winner of the 2014 Calibre Prize for an Outstanding Essay, worth $5,000. In this powerful essay, she writes about Japanese biological weapons and wartime experiments on living human beings.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

On 7 July 1989 the air was thick with heat in the Toyama district of Tokyo. Tsuyu, the rainy season, had just ended, leaving the atmosphere dense. At the former government health building location, a large pit was being dug for the new National Hygiene and Disease Prevention Research Centre. The workers buzzed around the site, their foreheads glistening in the sun. The mechanical digger plunged deep into the earth, scraping against rock as it brought up a mound of dirt. Something pale shone through the soil. At first, it looked like pieces of ceramic. On closer inspection, the workers realised it was human bones.

Twenty-five years later, their identities are still unknown.

In a city famed for skyscrapers and neon lights, Toyama is a quiet pocket in an urban jungle. Situated in the heart of Tokyo, only thirty minutes by foot from the world’s busiest train station, Shinjuku, it is bordered by busy Meiji Road at one end and the prestigious Waseda University at the other. In between lies residential housing, several schools, a public library, a Buddhist temple, the National Centre for Global Health and Medicine, and acres of leafy parkland. Hundreds of years ago, a lavish garden built by a feudal lord occupied the area. Now, at least a dozen public housing monoliths crowd the edges of the park.

Like most of metropolitan Japan, Toyama is full of contradictions. It is a place where the indigent and the upper middle class live side by side. In this suburb, an ancient Shinto shrine dedicated to gods of war is a short walk from the Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace, committed to exposing wartime violence and enabling justice for victims.

My first visit to Toyama was on 1 March 2013. The grass was tawny and the ground was thick with dry leaves, but I occasionally spied tiny green buds on the branches of trees. Mothers pushed prams through the park and up gently sloping alleys crowded with dwellings. Now and then, a door creaked or the murmur of a television sounded from within.

The idyllic snapshot of suburban life is worlds apart from Toyama’s former identity as a hub of military operations during the Asia–Pacific War. Seventy years ago, the neighbourhood was home to a mounted regiment, the Toyama Military Academy, and the Tokyo Army Medical College. The latter was a collection of buildings within a high-security, gated compound, where the Imperial Army’s medical élite, academics, and politicians gathered to share research and hold secret talks about Japan’s expansion into East Asia.

Few relics of that past remain. When Japan lost the war, the buildings were abandoned and many were eventually destroyed. The only structure still standing is a stone edifice that was once the meeting room of the Toyama Military Academy. It now forms the basement of the United Church of Christ.

‘Infected victims were vivisected to observe the progress of disease – sometimes without anaesthetic.’

The area’s unusual past might have stayed relatively obscure but for the accidental unearthing of the bones in 1989. News of the discovery of at least thirty-five human skulls prompted speculation. Some wondered if they were the victims of unsolved murders, while others thought they were the casualties of wartime raids or the 1923 Great Kanto earthquake. Kanagawa University history professor Keiichi Tsuneishi was one of the first to suggest ties to Japan’s covert biological warfare program during World War II. Tsuneishi, whose earliest work on the subject was published in 1981, knew of a special department known as the Epidemic Prevention Research Laboratory located within the Army Medical College. He was quick to draw links to Unit 731, the secret unit of the Army Medical College that developed biological weapons and experimented on living humans, starting in 1932 in the Japanese colony of Manchuria, and later in Guangzhou, Beijing, and Singapore. The unit conducted tests on bubonic plague, anthrax, cholera, typhus, smallpox, botulism, and poison gas. Infected victims were vivisected to observe the progress of disease – sometimes without anaesthetic. Test subjects were referred to as maruta, or ‘logs’, originally as a joke because the Unit 731 compound was disguised as a lumber mill, then the term persisted. Victims were political dissidents, common criminals, and sometimes poor farmers. They included the elderly, infants, and pregnant women.

About three thousand people were directly killed in the experiments at the Unit 731 compound alone. Japanese forces also deposited wheat, rice, and cotton riddled with disease-infected fleas near communities, and released typhoid and cholera into village wells. The total death toll resulting from the spread of disease is estimated to be between 250,000 and 300,000.

As the daughter of a Japanese immigrant, I have long been drawn to stories about Japan. In some ways, unravelling the mystery of the bones is my attempt to decipher a culture that is at once both familiar and unknown to me. Although I have lived in Japan several times since my childhood, I have always remained an outsider. Confronting the silences of Japan is a way of piecing together my cultural heritage. So I went to Japan to meet the unofficial guardians of the bones, concerned citizens who have no direct connection to the remains, but who have taken it upon themselves to see that justice is served.

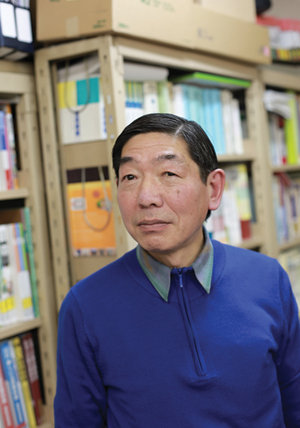

Yasushi Torii (photograph by Christine Piper)

Yasushi Torii (photograph by Christine Piper)

As I approached the north exit of JR Okubo station, two greying men waited for me. Yasushi Torii and Shigeo Nasu have dedicated much of the past two decades to exposing Japan’s wartime atrocities and assisting war victims. Torii, a high school biology teacher in his mid fifties, first heard about the unearthed bones while volunteering for a care organisation for disabled people in Shinjuku. One of his colleagues, Noboru Watanabe, told him that human remains dug up near his apartment in Toyama were presumed to be linked to Japan’s biological warfare program. In 1991, Watanabe joined a group of concerned citizens on a trip to China to learn more about the program. They met families of Unit 731 victims and attended an exhibition about the unit. He returned the following year, and Torii went with him. ‘Back then, I didn’t really know anything about the bones, I just followed,’ Torii said. ‘That was actually my very first overseas trip. Of course, after listening to the voices of the local people, I was shocked. From then on, I decided to be actively involved.’ Torii is now the president of the Association Demanding Investigation Into the Human Remains Found at the Former Army Medical College Site, a citizens’ group founded by his friend Watanabe and several others. ‘The group’s primary aim is to return the bones to their families, or if the family can’t be determined, at least back to their home country.’ Since 1996 the association has been conducting annual walking tours for the public to visit sites related to Japan’s secret wartime past. The walk usually takes place in early April, while the cherry blossoms are in full bloom, but Torii and Nasu agreed to guide me during my short trip to Tokyo on the cusp of winter and spring.

Nasu is a member of the Centre for Victims of Biological Warfare, an organisation campaigning for recognition, an apology, and compensation from the Japanese government. The group also aims to educate people and bring to light other details of Japan’s bio-logical warfare program, such as the use of poison gas. Now retired, Nasu was working as a security guard at a hospital when he heard about the families of Unit 731 victims’ compensation claim at the Tokyo district court. ‘Since I worked the night shift, I had plenty of time during the day, so I decided to support them,’ Nasu said. ‘Once you know only a little about this war, you’re forced to want to get involved to do something about it.’

A mild wind blew as Torii, Nasu, and I set off from Okubo station. Our final destination was the National Hygiene and Disease Prevention Research Centre in Toyama, where the bones currently rest inside a granite monument. Torii quickly took the lead, charging ahead to point out places of interest. Nasu kept to the back of our small group, often wandering off to inspect this or that. On the main street of Okubo, home to bustling Korea Town, signs advertising Korean barbecue and massage parlours flashed thinly in the morning light. We stopped in front of an ordinary-looking Japanese funeral parlour.The window displayed three wooden altars with double doors open to reveal Buddha figurines inside. My grandfather had an altar just like these in his home on the outskirts of Tokyo.

Torii gestured to the funeral parlour. ‘This is the place where people who die in Shinjuku ward who can’t be identified are kept. In 1989, after the bones were found, they were stored in the basement here until March 2002, when they were interred inside the monument.’

The story of the bones is a long one. Even now, twenty-five years after they were discovered, it is still unresolved. The reasons are complex: the accumulation of a number of court cases and appeals, combined with ordinary bureaucratic delays and an extraordinary lack of institutional cooperation. After the bones were discovered, the police investigated the remains and found they belonged to men and women who had died at least twenty years earlier, and that there was no evidence of violent crime. They concluded that even if the deceased had been victims of crime, they had been buried for more than fifteen years, so the statute of limitations had passed. The police dropped the case and public interest waned. The Ministry of Health and Welfare, on whose property the remains were found, agitated for a cremation, as is the custom in Japan. With that, the inconvenient discovery would have been finally dispatched. Yet the Shinjuku ward local government refused to drop the matter, repeatedly requesting the ministry launch a full investigation. Each time they were refused. ‘We have no obligation to investigate just because we own the land,’ said ministry official Nobuhisa Inoue. In a rare act of defiance, the then-mayor of Shinjuku, Katsutada Yamamoto, launched an independent investigation using local government funds. He approached world-renowned physical anthropologist Hajime Sakura, director of human research at the National Science Museum.

‘Professor Sakura was really interested in doing it, but the head of the museum denied, saying it was out of the scope of the museum. But I’m not sure it was the real reason,’ Torii explained, hinting that other forces were at work. On the advice of the Human Remains association, Shinjuku ward next approached specialists at Jikei University School of Medicine in Tokyo and St Marianna University School of Medicine in Kanagawa. ‘In both those cases, the individuals were willing to do it, but the universities denied.’

It seemed whichever way they turned, they were met with silence.

A few days earlier, on a wet winter’s day, I met Kazuyuki Kawamura, a former Shinjuku ward assemblyman. As I walked to his workplace in Shinjuku, cold rain pelted down and touched my skin through my jacket. Kawamura greeted me with a smile. His office was lined with shelves stacked high with books, folders, and cardboard boxes. Desks laden with paper crowded the middle of the room.

Kazuyuki Kawamura (photograph by Christine Piper)

Kazuyuki Kawamura (photograph by Christine Piper)

While the foyers of commercial buildings in Japan are uniformly stark and clean, almost every office I have visited is a domain of disarray, seemingly at odds with the Japan of carefully controlled tea ceremonies and minimalist design. Homes reflect a similar divide: the sitting room, where guests are received, are ordered and aesthetically harmonious, while the rest of the house is often chaotic. The tidy exterior versus the cluttered interior points to the dichotomy at the heart of Japanese culture: the conflict between honne (personal feelings and desires) and tatemae (public façade).

As we sat down at the hodgepodge of desks, Kawamura described the tension in the ward office as officials deliberated over what to do about the ‘troublesome’ discovery. Although they believed the ministry should manage the site, the ministry’s refusal to conduct an investigation played on their conscience. The Shinjuku local government office eventually announced it would pursue an independent investigation, a decision that Kawamura described as ‘very courageous’.

Shinjuku ward’s first choice to analyse the remains, anthropologist Hajime Sakura, eventually agreed to the project, but only after his retirement from the National Science Museum. He carried out the research in the basement of the funeral parlour in Okubo, where the bones were stored. In April 1992 he reported his findings: in addition to the thirty-five easily recognisable skulls, there were 132 skull fragments, thirty spines, six chest bones, thirteen thigh bones, and seventeen neck bones from at least sixty-two, and possibly more than a hundred people. The remains were from Mongoloid men and women who had died ‘from several tens of, to one hundred years’ earlier. More than ten skulls had holes from bullets or drills, and cuts by ‘perhaps Japanese swords’ made after death. He also found evidence of experimental surgery or surgical practice, as most of the skulls bore scalpel or saw marks, but he could not prove a definitive link to Unit 731, as the bones did not show any particular signs of disease.

Following Sakura’s report, the Ministry of Health and Welfare agreed to launch an investigation to determine the origin of the bones. They began conducting interviews and questionnaires with former Army Medical College personnel. But then Shinjuku ward did an about-face, announcing its wish to cremate the bones. The new mayor, Takashi Onda, believed that as a definitive link to Unit 731 had not been found and since there was no one to claim the remains, they should be cremated according to law – a move that Kawamura opposed. ‘By cremating the bones, we would lose the evidence – that was what we feared most. At that point, I realised we needed some kind of movement.’ In 1997, he formed the Citizens for the Investigation of World War II Issues – a group that aims ‘to verify from a neutral point of view the victims of the war’.

‘Something pale shone through the soil. At first, it looked like pieces of ceramic.’

Like many of the people I interviewed in Japan, Kawamura has long been involved in grassroots politics. As a university student, he protested against the Japan–United States security treaty renewal in 1970, demanding the removal of American troops in Okinawa. He joined the socialist party and in 1979 was elected to Shinjuku local government, where he served for twenty years. Kawamura was born in 1952, a few years after his father returned from China, where he had fought during the war. ‘At the start of the war, my father was an English teacher at a girls’ school. He and the other teachers were summoned to the war zone in China. It was a form of conscription – they couldn’t refuse.’

I wondered whether his father’s military past impelled Kawamura to seek justice for war victims. But he told me the reverse actually occurred:

Because I became involved in these issues as a student, I decided to ask my father about his experience ... he talked to me about it. He didn’t even want to go to war, but he was forced to. During his training in China, he was ordered to use a bayonet to kill Chinese people [for practice].

I froze. I had read about Japanese soldiers practising bayonet technique on Chinese prisoners before, but hearing it in those terms – someone’s father, who had previously been an English teacher at a girls’ school – stopped me cold. I tried to imagine one of the teachers at my all-girls high school being sent to war and then having to spear a helpless prisoner. Mr Hartley, or diffident Mr Lacey. It was impossible to conceive.

Kawamura’s father was captured as a prisoner of war and forced to do hard labour at a coal mine in the former Soviet Union for three years after the end of the war. He died recently at the age of ninety-two, six months before the Japanese parliament finally enacted a bill to compensate former POWs interned in the Soviet Union. Kawamura continued speaking about his father, but I could not stop thinking about what it would be like to face another human being one moment, then drive a bayonet into his chest the next. I tried to steer Kawamura back to his prior revelation.

‘Did your father’s experience in China affect him deeply?’

Kawamura considered my question for a moment, his left eyelid drooping in concentration.

‘I don’t think he was that affected. He spoke about his stories quite calmly.’

Torii, Nasu, and I crossed Meiji Road and entered the outskirts of Toyama. A path bordered by a green hedge guided us towards the park. From somewhere to our right, the chatter of school children reached us on the wind. I felt a shift in the atmosphere as we left the concrete matrix of urban Tokyo behind.

We stopped at a dusty expanse bordered by low shrubs and trees. There was hardly a soul in sight.

‘See that tall tree?’ Torii pointed to a lone zelkova in the middle of the expanse. ‘That’s the probable former location of the Epidemic Prevention Research Laboratory.’

The Laboratory, located in the grounds of the Army Medical College, was Shiro Ishii’s Tokyo base and the hub of his biological warfare empire. Ishii established it in 1932 as a facility to develop biological weapons. Even within the highly secure Army Medical College, access to the laboratory was restricted. Ishii’s initial experiments went well, but he wasn’t sure whether they would work in the field, so he pursued human testing. Aware of the limitations of being based in Japan, Ishii looked to the new Japanese colony of Manchuria in northern China, and opened his first overseas base in Harbin in 1932. Historians such as Keiichi Tsuneishi believed the bodies of murdered test subjects were sent from China to the Tokyo laboratory for further analysis. But as Sakura’s analysis of the remains did not find a definitive link to Unit 731, and with no witnesses to confirm it, the connection remained conjecture.

Koeisha funeral parlour in Okubo, where the bones were kept for thirteen years (photographed by Christine Piper)

Koeisha funeral parlour in Okubo, where the bones were kept for thirteen years (photographed by Christine Piper)

In 2001, the Ministry of Health and Welfare finally released its report on the remains, almost ten years after it announced it would pursue an investigation. Based on interviews and questionnaires completed by 368 former personnel, the ministry determined the corpses were probably used by the college for educational purposes. The report raised the possibility that some of the bodies were transported from war zones, but did not offer a reason for this. In a win for the Human Remains association, the report recommended that the bones be preserved rather than cremated, but it concluded they were not connected to Unit 731 and there was no need to further investigate. On a rainy day on 27 March 2002, the remains were finally moved from the funeral parlour in Okubo and ceremoniously interred beneath a three-foot-high granite repository in the grounds of the National Hygiene and Disease Prevention Research Centre. ‘These are human remains, not just any object. It’s only appropriate to pay due respects,’ ministry official Makoto Haraguchi said. By interring the bones, he no doubt hoped to close a difficult chapter in the ministry’s history.

The controversy might have waned but for eighty-four-year-old Toyo Ishii (no relation to Shiro Ishii). Ishii was in her early twenties when she was employed at the Army Medical College as a nurse in the oral surgery department. Ishii broke decades of silence when she revealed that she was ordered to dispose of corpses, body parts, and bones in the final weeks of the war as American forces approached. ‘We took the samples out of the glass containers and dumped them into the hole,’ she wrote in a statement released in June 2006. ‘We were going to be in trouble, I was told, if American soldiers asked us about the specimens.’ Ishii said she was never involved in nor knew about experiments on humans, but often saw body parts in glass jars and bodies floating in pools of formalin in the hospital’s three morgues. She identified two other areas near the Army Medical College where she was instructed to dispose of the bodies.

Ishii’s testimony, more than anything else I had read about Unit 731, struck a chord. I was fascinated by the internal and external forces that conspire to keep someone silent. Ishii first began to talk about her war memories in 1998, when Shinjuku ward began gathering war crime testimonies. After she spoke about her employment at the College, members of the Human Remains association and the Minister for Health and Welfare arranged to meet her. ‘I don’t think Ishii originally intended to proactively testify. Even when meeting us, she showed trepidation,’ Torii said. Ishii regretted the hasty disposal of the remains and wanted some sort of monument created for them. She was happy after the monument was erected, and died in 2012.

Toyo Ishii was not the only one to testify. Several dozen Japanese have shared their stories about their involvement in Japan’s biological warfare program. As part of a travelling exhibition about Unit 731 that Torii and Nasu helped to stage in 1993, many former Unit 731 members publicly discussed their experience for the first time. Ken Yuasa spoke at several locations about his time as a young army doctor in China. ‘This is not easy for me to speak about, but it is something I must confess,’ he began, as quoted in Unit 731 Testimony by Hal Gold. ‘What I did was wrong. It is also true that it was forced on me by the government, but that does not reduce the size of my crime.’ Yuasa described the first time he vivisected a man, an old Chinese farmer. Despite his revulsion, he went through with it, saying he had always been the type of person to follow orders:

If you made a disagreeable face [at being ordered to do a vivisection], when you returned home you would be called a traitor or a turncoat. If it were just me alone, I could tolerate it; but the insulting looks would be cast on parents and siblings. Even if one despises an act, one must bear it ... That was my first crime. After that, it was easy. Eventually I dissected fourteen Chinese.

Toyo Ishii’s disclosure prompted the ministry to conduct an excavation in 2011, the specific intent being to find more buried human remains. But after a comprehensive dig that lasted months, no remains were found – only plaster casts and prosthetic limbs used by the adjacent hospital, eerily symbolic of the human body parts that activists hoped to find.

We emerged from the park into the open area surrounding Toyama Heights public housing apartments, where Torii’s friend and colleague Noboru Watanabe used to live. A warm southerly whipped between the buildings, stirring up debris. I blinked against the dirt, my feet heavy as we walked into the wind. Torii paused in front of me and pointed to the sky. ‘Haru ichiban.’ The first storm of spring.

The National Centre for Global Health and Medicine rose up to our left, a huge multi-storey complex. It was formerly the First Imperial Army Hospital during the war. Army Medical College personnel used to live just across the road, but little was evident of that past in the concrete high-rises and cement-rendered dwellings. The area was heavily bombed towards the end of the war, and the resulting firestorm destroyed most of the buildings and left at least 100,000 civilians dead.

We momentarily lost our way in the narrow alleys between houses and apartment blocks before finding our target: the site of Shiro Ishii’s former apartment. Although I knew the original building was no longer standing, I was disappointed to detect nothing sinister in the curved staircase and off-white bricks of the low-rise block.

‘The tidy exterior versus the cluttered interior points to the dichotomy at the heart of Japanese culture ... ’

Shiro Ishii, dubbed the Josef Mengele of Japan, was the mastermind of Japan’s biological warfare program. He was born in Chiba prefecture, about two hours from central Tokyo. His family, wealthy and influential, exercised a kind of feudal dominance over the locality. This would prove useful in later years, as Ishii hand-picked many staff for the Epidemic Prevention Research Laboratory and other units from the population in his home town, knowing they couldn’t refuse or speak against him owing to their allegiance to his family. From an early age, Ishii hoped to serve his country in the military. In 1920, less than a month after finishing his undergraduate medical degree, he joined the Imperial Army and became an ardent supporter of the ultra-nationalist faction.

Ishii was a gifted pupil with an extraordinary memory and almost superhuman energy. His real brilliance, however, was his political shrewdness. Sycophantic to his superiors and domineering to his subordinates, Ishii was adept at manipulating others for his own benefit.

In 1927, Ishii read a report that immediately piqued his interest. It concerned the 1925 Geneva Protocol banning the use of chemical warfare. If it was banned, he reasoned, it must be powerful, and so began his lifelong interest in biological warfare research. Ishii lobbied for the military to conduct research into germ warfare, but it wasn’t until 1930 that the army leaders and political atmosphere were receptive to his requests. That year, he became professor of immunology at the Tokyo Army Medical College and was promoted to a major within the army, thus beginning his rapid advancement through the ranks.

Shiro Ishii

Shiro Ishii

Ishii was regarded as both eccentric and brilliant. Although he had detractors, such as army Surgeon General Hiroshi Kambayashi, who labelled him an ‘ambitious boaster’, his opponents were in the minority. Amid the nationalist fervour of the new decade, Ishii was able to convince his superiors that biological warfare was the way of the future. In 1932, the dean of the Army Medical College, Chikahiko Koizumi, set aside funds and land to create a building for Ishii’s use. From there, Ishii expanded his biological warfare operation to Manchuria, and then to other parts of China and Singapore.

In the paper, ‘Japanese Pacifism: Problematic Memory’, Mikyoung Kim explores the conflicted nature of Japan’s postwar collective memory, entangled as it is with Japan’s multiple identities: Asia–Pacific aggressor, nuclear bombing victim, and postwar pacifist advocate. Referencing the ideas of psychologist Hayao Kawai and sociologist Takeshi Ishida, Kim cites the ‘empty centre’ at the core of Japanese mind and culture as the reason for the perceived Japanese moral ambiguity towards their wartime past:

The empty centre, asserts Ishida, embodies a situational logic for conflict avoidance, not necessarily conflict resolution. The end result is temporary pacification, not permanent reconciliation ... Because aesthetic principles take higher priority in the Japanese mind than moral aspirations … tensions aroused by the cultural dichotomies of tatemae-honne (front vs. honest inner feelings) and omote-ura (visible vs. hidden layers of self) are mitigated. In terms of Kawai and Ishida’s mental topography, this is because they are resolved [sic] of the vacuous centre which filters out moralistic sentiments. The Japanese are therefore inclined to perform situationally appropriate actions divorced from genuine feelings ... As the empty centre filters out the unpleasant engagements with one’s own sins, difficult memories make the past unusable.

Japan has repeatedly been accused of ‘historical amnesia’ in relation to its wartime aggression, due to the government’s reluctance to officially apologise to victims, and also because of several history textbook controversies from the 1950s to today, in which ministry-approved textbooks were censored or revised to downplay Japan’s aggression in Asia. Yet certain trends in the population run counter to this idea of wilful forgetting. Seiichi Morimura’s book about Unit 731, Akuma No Hoshoku (The Devil’s Gluttony, 1981), sold 1.5 million copies in Japan and catapulted Japan’s biological warfare program into mainstream consciousness. From July 1993 until December 1994, the Unit 731 exhibition organised by Torii, Nasu, and others, toured sixty-one locations in Japan and attracted more than 250,000 visitors. Their popularity indicates that Japanese people are not amnesic, but are in fact deeply engaged with their wartime past.

The postwar trend to diminish and conceal past atrocities, and the more recent movement to expose and learn more about Japan’s conflicted past reflect a schism within society. In Japan’s Contested War Memories (2007), media scholar Philip Seaton argues for a pluralistic view – one that highlights the diversity of contested war memories in Japan:

[T]he term ‘memory rifts’ symbolises the divisions deep beneath the surface ... [T]here is a rift between, on the one hand, liberal Japanese (‘progressives’, shinpoha), who see apology and atonement for the past as the best way to restore self-respect and international trust; and on the other hand conservatives, who see a positive version of history and commemoration of the sacrifice of the war generation as the best way to achieve national pride.

My second visit to Tokyo to research the human remains followed in May 2013, when the city was in the full thrust of spring. Vegetation crowded the parks in near-violent abundance. Children dawdled on their way home from school, woozy in the sun. The drab palette and brisk wind of two months previous had vanished. Tokyo was a different being; the city felt entirely new.

With my surroundings rinsed clean of winter’s torpor, I met Norio Minami, the lawyer engaged in the lawsuit to halt the cremation of the bones. His office was a short stroll from Shinjuku Gyoen, the manicured park with elaborate Japanese and European-style gardens that was once the domain of a feudal lord.

As the first human rights lawyer I had ever met, Minami was not what I expected. I had envisaged a gruff, sports jacket-wearing type, weary from the vicissitudes of life. With his thick, wavy hair and trim navy suit, Minami looked more like a classical composer. Throughout the two hours we spent talking, Minami was earnest and unfailingly polite.

Norio Minami (photographed by Christine Piper)

Norio Minami (photographed by Christine Piper)

As we sat inside a partitioned enclosure within his office, Minami explained that he had become involved in the case of the human remains because of his interest in the civilian activism movement. Through his contacts, a group of concerned citizens, headed by Keiichi Tsuneishi and whose members included Torii, approached him. Local governments in Japan are legally obliged to cremate unidentified bodies, and the group wanted to take legal action to prevent that outcome: ‘I knew from the beginning we wouldn’t win the case … But by raising the issue we thought we could get public attention and make people aware of the fact there were many human bones found that remain unidentified … and by that, stop the cremation.’

Minami, who is fifty-nine, contacted former Unit 731 members to gather evidence for the case. One of the people he approached was Mr Okada (not his real name), who had an administrative role within the Epidemic Prevention Research Laboratory. In the postwar years, Okada had become involved in the peace, democracy, and anti-nuclear movements, and so he initially co-operated with Minami. At the first few meetings, Okada talked about the unit’s experiments with bacteria and rats, but he didn’t say anything about human experimentation. It wasn’t until the third or fourth interview that Okada divulged that he had been involved in human experimentation in China:

He eventually revealed to me he killed people ... This was a fact he never disclosed to anyone else, not even his family members … his wife, kids – nobody … When I later asked for permission to include that part in his statement, he became vague, saying, ‘I don’t really remember ...’

Okada had agreed to testify in court, but on the day he was due to appear he said he wasn’t feeling well and couldn’t go. He eventually provided a written statement that made no mention of human experimentation. ‘I’m sure he really wanted to confess. It must have been a weight on his heart for a very long time … I’m sure he wanted to, but he could not. People were pushed into such a situation because the government did not admit what happened. That led me to be involved in the lawsuit to sue the government for not admitting the atrocities.’

I asked Minami whether he pitied the Unit 731 members because he felt they had no choice. He looked down, deep in thought. Strain showed in the folds of skin around his eyes. ‘That is a very difficult question,’ he said. ‘If I look at the situation from a third-person point of view, I think: there must have been other ways. But if I put myself in the shoes of the former members, if I were really there – I don’t know. There is a high possibility I would have committed the same things. I have interviewed many former Unit 731 members who told me they eventually became numb … I can’t say I would not turn into one of those people … Humans are weak. You never know what you might do.’

In the low hum of his office, filled with the murmur of voices, the whirr of the copier and the occasional trill of telephones, Minami reflected on the silences of the past – silences decreed by institutions and enacted by individuals. Through the judicial process, Minami hoped to foster relief by encouraging perpetrators to speak out. ‘I knew [the former Unit 731 members] were suffering … [T]hey were suffering because of their guilt and they couldn’t speak out. I wanted to release them, in a way.’

In 1995, Minami filed a compensation claim at the Tokyo District Court on behalf of families of Chinese victims of Unit 731 experimentation. Through his involvement in the case, Minami became close to several of the plaintiffs:

There is one woman whose husband was sent to Unit 731 for experimentation … When we visited the place where she was tortured by the Japanese military police, she insisted I stay at her house because, she said, ‘You’re my son.’There is another lady who was a victim of the Nanjing Massacre. When I interviewed her, her son came. During the interview, the son said something to his mother, and she started berating him. I asked the interpreter what they were talking about. Apparently the son said, ‘Since we need to buy medicine and other necessities, maybe you should ask him for some money.’ She rejected the idea immediately and told her son to get out of the room, which he did. These were the moments when I felt what I had been doing paid off. There were many moments when I wanted to quit. There were times I spent more money than I earned. But these encounters, these relationships and the feeling of connection has been invaluable … this comes from human relationships and the fact we believe in each other.

The court rejected the compensation claim in 2002, on the grounds that China had waived its rights to war reparations when it signed the 1972 Japan–China peace treaty, establishing diplomatic relations between the two countries. Despite the plaintiffs’ loss, they achieved one breakthrough: the court acknowledged the existence of Unit 731 and its ‘cruel and inhumane’ activities in China – the first time a court in Japan had done so. The legal team appealed the ruling, but the case was eventually rejected by the Supreme Court.

One of the reasons why Japan has hitherto failed to come to terms with its past is that many of the perpetrators of war crimes returned to positions of power. Minami said: ‘Germany was able to carry out objective war compensation, because none of the former Nazi members became a part of the régime after the war. Whereas in Japan, those responsible for wartime atrocities remained within the régime.’ An example of this continuation of power is the current conservative prime minister of Japan, Shinzo Abe, who is the grandson of Nobusuke Kishi, minister of commerce and industry from 1941 to 1945 and prime minister from 1957 to 1960. As a member of Japan’s war cabinet, Kishi oversaw the forced conscription of hundreds of thousands of Korean and Chinese labourers. He spent three years in prison as a suspected Class-A war criminal, but was never tried.

‘One of the reasons why Japan has hitherto failed to come to terms with its past is that many of the perpetrators of war crimes returned to positions of power.’

‘Another reason,’ Minami continued, ‘was Germany was surrounded by developed countries that demanded Germany’s responsibility for the war. Whereas Japan was surrounded by developing Asian countries, so the pressure was relatively low. Japan was a large economic power, so the other Asian countries thought they had to put up with Japan’s refusal to make amends for its past actions.’ Japan’s nuclear bomb victim identity further complicated matters, as international pressure on Japan to make amends for its wartime aggression was diminished due to the bomb’s devastating legacy.

Shiro Ishii and others connected to Japan’s biological warfare program escaped prosecution through a secret immunity deal with the United States. At the end of the war, with the Russians poised to invade Manchuria, Ishii instructed staff at the units to kill remaining prisoners, destroy all evidence of experimentation and dynamite the compounds. Plague-infested rats were released into local areas, causing an outbreak of the disease that eventually killed 30,000 people. Ishii returned to Japan, where he spent several years in hiding and even fabricated a story that he had been shot dead. Meanwhile, tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union were rising, with both nations eager to access data from Japan’s biological warfare research to use for their own military advantage. The United States brokered a deal first, agreeing to exempt the leaders from prosecution for war crimes in exchange for the data. Edwin Hill, the chief of US Army Chemical Corps at Fort Detrick in Maryland, reported that the information gained from Japan’s biological warfare program was ‘absolutely invaluable’, ‘could never have been obtained in the US because of scruples attached to experiments on humans’, and ‘was obtained fairly cheaply’ (as quoted in Factories of Death by Sheldon Harris [2002]). At the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal), only one reference to ‘poisonous serums’ used on Chinese civilians was made. It was swiftly dismissed due to lack of evidence. A year later, in late 1949, the Soviet Union held a separate tribunal, the Khabarovsk War Crimes Trials. All twelve accused Japanese military personnel were found guilty of manufacturing and using biological weapons, with sentences from two to twenty-five years at a Siberian labour camp. However, all were released back to Japan by 1956; the longest sentence served by anyone connected to Japan’s biological warfare research was seven years. Neither Shiro Ishii, nor the second commander of Unit 731, Masaji Kitano, nor Ishii’s deputy at the Epidemic Prevention Research Laboratory, Ryoichi Naito, were ever tried.

‘Humans are weak. You never know what you might do.’

In the decades following the war, former bacteriological warfare scientists became presidents of universities, deans of medical schools, and representatives of government agencies, many receiving public honours. ‘[O]nce freed of the danger of war crimes trials, alumni of the biological warfare units were able to assume leading roles in the postwar Japanese medical and scientific communities,’ writes Sheldon Harris in a chapter of Military Medical Ethics, Volume 2 (2002). Naito Ryoichi went on to found the Green Cross Corporation in 1950. It became one of Japan’s leading pharmaceutical companies, until it was rocked by scandal in 1998 when it was found guilty of selling HIV-infected blood, leading to at least 400 deaths.

Ishii’s activities after the war are unclear. Some historians believe he went to Maryland to advise the United States on bioweapons, while Ishii’s daughter Harumi maintains he stayed in Japan and opened a clinic, dedicating himself to the welfare of children. In any case, while most of his colleagues advanced their careers, Ishii withdrew from public life. He died at home of throat cancer in 1959. According to his daughter, he converted to Catholicism in his final years, which seemed to bring him peace.

In Minami’s office in Shinjuku, the room was quiet. It was past six o’clock in the middle of Golden Week holidays, and nearly all the other workers had gone home. Darkness was gathering outside. Almost two hours into our discussion, Minami was still carefully choosing his words, the same sincere expression on his face. If not for people such as Minami, agitating for change, the matter of the bones would have fallen into obscurity in Japan long ago. ‘In the case of Germany, it was more of a top-down decision. The government made a decision to compensate, and this was handed down to the people,’ he said. ‘But in Japan, this approach is difficult to achieve. You have to change the society – change the people – first, and then there will be a bottom-up movement that will eventually change the attitude of the government. But this will take time.’

The National Institute of Infectious Diseases sits atop a hill adjacent to Toyama Park. The bricks of the low-rise building are a pale cobalt blue – perhaps the architect’s attempt to give the building some cheer. Torii, Nasu, and I entered through the sliding glass doors and provided our details for the visitor register. After a few minutes, a guard appeared and started escorting us towards the monument for the bones. Torii, pausing in front of an alcove at the corner of the building that framed a network of pipes, said: ‘This is where the bones were found in 1989. In the basement, to be exact. That spot is currently used as the library, meaning the people researching in the library are doing that together with the bones.’ He spoke with a slight smile.

As we continued down the path, anticipation rose inside me. The monument to the unidentified bones was the highlight of the walk. Not only is it a memorial to the unidentified victims, it is also a symbol of Japan’s contested memory – a permanent and a temporary resting place, depending on whose view one takes. The members of the Human Remains association still hope to DNA-test the bones and send them to their village of origin, although very little progress has been made in the past decade. Before my visit to Japan, I had seen the monument in photos online, but I wanted to see it in person to pay my respects.

The monument to the bones erected by the ministry in 2002 (photographed by Christine Piper)

The monument to the bones erected by the ministry in 2002 (photographed by Christine Piper)

I looked up. Silver clouds shredded the sky. We walked a few more steps, turned a corner, and then I saw it. Beneath the branches of a cherry tree, the memorial sat, all sleek black lines and sharp corners, a symbol for clean, ordered Japan – the Japan of tea ceremonies and minimalist design. Although it was a suitably grand structure, the block of granite seemed to speak of the anonymity of the bones and of the cruelty of the régime that carried out the killings. A plaque affixed to one side read:

On this site stood the former Army Medical College until 1945. In July 1989, when Toyama Research Office was due to be constructed, human remains thought to be specimens belonging to the Army Medical School were excavated. This plaque is to offer our deepest condolences to the deceased.

Ministry of Health and Labour, March 2002

At the rear of the monument, cement steps descend to a metal door. Inside, the bones are stored in fourteen wooden boxes stacked on metal alloy shelves. I imagined them jumbled together, like the clutter of offices in Japan, so often hidden from public view. For years, the bones were stored in cardboard boxes at the funeral parlour, until one of the victims’ relatives visited Japan and demanded to know whether any progress had been made regarding them. ‘The answer she received was that the bones were moved from cardboard boxes into wooden boxes,’ Torii said.

Where we stood at the top of the hill, the wind was strangely absent. It was quiet, almost preternaturally so. Someone was playing tennis nearby. I heard the pop of a ball hit back and forth, a metronome to our solemnity. It brought to mind every case brought to court, the rejections and appeals, the constant back and forth – a game of perseverance, drawn out over years.

My mood was sombre as I tried to think of the people to whom the bones once belonged. But with the remains hidden inside the obelisk, I struggled to feel any true connection or to grasp the extent to which they had been wronged.

Two kanji characters are inscribed on the monument’s polished flank. ‘Seiwa’is how they are read. It is an invented word, chosen by someone within the ministry, combining two common characters for ‘quiet’ and ‘peace’. Although ‘quiet peace’ would be a fitting epitaph for most tombstones, in light of the unique situation of the remains, it seems a particularly cruel irony. Almost seventy years after the end of the war and twenty-five years since the discovery of the remains, the 233 human bones are still waiting, still silent.

The Calibre Prize for an Outstanding Essay was first presented in 2007 and has become Australia’s premier essay prize. Originally sponsored by Copyright Agency (through its Cultural Fund), Calibre is now funded by Australian Book Review. Here we gratefully acknowledge the generous support of ABR Patron Mr Colin Golvan SC.