- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The art of Nick Cave

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Lecturing in Vienna in 1999, Nick Cave outlined his theory on the nature of the love song. ‘Within the fabric of the Love Song … one must sense an acknowledgement of its capacity for suffering.’ Unless pain and longing simmer beneath the surface of the music, it isn’t a love song at all. What Lorca referred to as ‘duende’ and Cave himself calls ‘an inexplicable sadness’ at the heart of the love song is evidenced in even the most cursory sampling of his oeuvre. From the despairing lilt of ‘Where Do We Go Now but Nowhere’ to the apocalyptic cheer of ‘Straight to You’, the darkness and desperation of love are constants in his work.

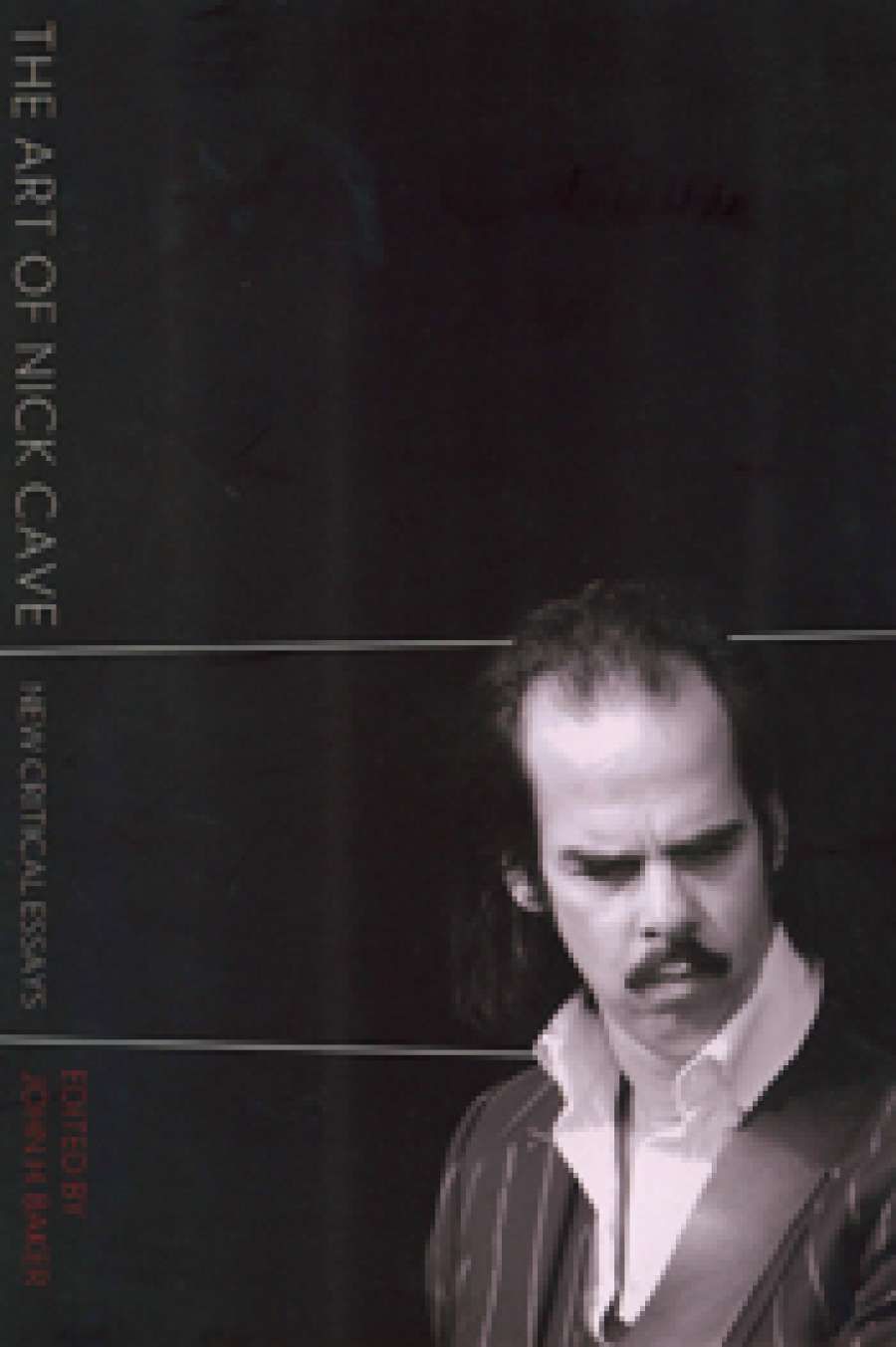

- Book 1 Title: THE ART OF NICK CAVE

- Book 1 Subtitle: NEW CRITICAL ESSAYS

- Book 1 Biblio: Intellect (Footprint), $59.95 pb, 288 pp, 9781841506272

The Art of Nick Cave, a collection of critical essays edited by John H. Baker, addresses the entirety of Cave’s career, including his two novels, his screenplays, and his compositions for film and theatre. It is an ambitious undertaking, considering the three decades of output involved, and would have benefited from a tighter focus. As with much collated material, it is an uneven and piecemeal assembly.

The loose disparity of the canon itself may be the reason why the essays fail to make a convincing whole. The screenplay for The Proposition (2005) and Cave’s performance in Ghosts… of the Civil Dead (1988), not to mention the compositions for the theatre, aren’t really germane to the music, despite admirable efforts by some of the academics to suggest otherwise. Even the more relevant analysis of the novels – thematic cousins to the music as they are – fail to shed much light.

‘Unless pain and longing simmer beneath the surface of the music, it isn’t a love song at all.’

The essay by Karoline Gritzner on the theatrical compositions is no more than a prosaic descriptor, and Paul Lumsden’s piece on the pedagogical benefit of Cave’s lyrics in his university classroom also seems a needless addition. Much better are the essays that deal with the lyrics, providing as they do a kind of accidental intertextuality, layering analyses on top of each other. And divorced from the music, Cave’s words do carry a certain poetic heft. His fondness for religious iconography is infamous, as is his predilection for violent and scatological imagery, but what shines through these essays is a mind genuinely grappling with the twin entices of the sacred and the profane. Cave may some-times refer to God ironically, but his wrestle with theology is utterly sincere. He is rather like film-maker Paul Cox in this regard: willing to face issues of spirituality with disarming honesty when most Australian artists simply don’t.

It does, however, result in a lot of whores and serpents and nails and blood. Cave himself acknowledges an adolescent fascination with Old Testament tropes, finding the concept of a ‘whacked-out God tormenting a wretched humanity’ oddly comforting following the sudden death of his father. It clearly informed the majority of The Birthday Party’s song-writing and much of the early work of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds.

Cave didn’t exactly turn away from biblical references around the time of The Boatman’s Call (1997). He merely shifted his focus to the New Testament and the redemptive promise of the Christ figure, though, as is mentioned in John H. Baker’s own contribution to the collection, ‘There is a Kingdom: Nick Cave, Christian Artist?’, Cave’s ‘new fascination with Christ was not conventionally Christian’. Christ seems representative of the creative act itself, and the irony at play in a song like ‘Into My Arms’ – where the narrator opens with the line ‘I don’t believe in an interventionist God’, but spends each chorus crooning ‘Into my arms, O Lord’– indicates that Cave’s attitude to religion is ambivalent at best.

Some essays locate Cave in the Gothic tradition, in particular Isabella van Elferen in her contribution ‘Nick Cave and Gothic: Ghost Stories, Fucked Organs, Spectral Liturgy’. A convincing portrait of influence is sketched here, one that is capable of embracing Yeats and Milton as casually as it does Freddy Krueger and Robert Mitchum. Considering the proliferation of crows, cowboys, and ammunition in Cave’s back catalogue, and the spectral excess on display in an album like Murder Ballads (1996), it isn’t such a stretch to trace a line back through film noir and horror to Faulkner and Poe.

But these literary influences, while astute and compelling, are not much help when we turn to the actual music. Only two of the essays deal more than casually with Cave’s music, and only one with true vigour. David Pattie’s ‘A Beautiful, Evil Thing: The Music of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ troubles itself with the dichotomy of music and noise in Cave’s work. He identifies Blixa Bargeld and Warren Ellis, not surprisingly, as the twin forces at work on Cave’s idiosyncratic sound. The dissonance, atonality, and disharmony that these two musicians produce sit alongside the often lush melodies, creating in one instance ‘what can only be described as the sound of the Bad Seeds being thrown down a flight of stairs’.

This is excellent, and a fine example of genuine ekphrasis breaking through the sometimes tedious academese that mars many of these otherwise thoughtful essays. Cave’s father was an English teacher, and Cave himself admits to a dread of becoming a dry literary figure. One only need play the songs as accompaniment to these essays – to hear the unmistakably plaintive echo of ‘duende’ in them – to know that there is little chance of that.

Comments powered by CComment