- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Extraordinary ascensions

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the 1960s she was deemed an Irish Jezebel. After the publication of her début novel, The Country Girls (1960), the local postmistress told her father that a fitting punishment would be for her to be kicked naked through the town.

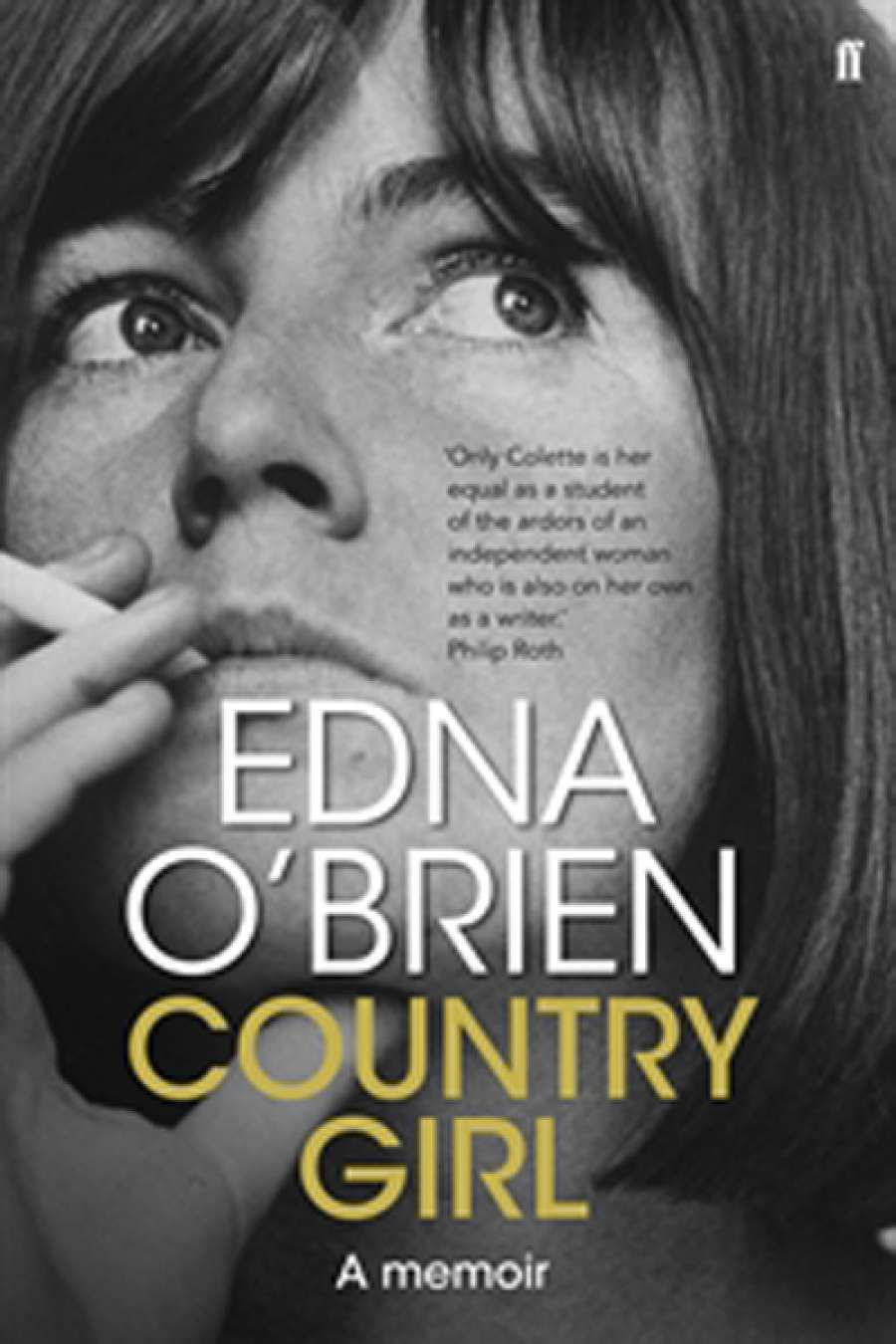

- Book 1 Title: Country Girl

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Faber and Faber, $35 hb, 339 pp, 9780571269433

- Book 2 Title: The Love Object

- Book 2 Subtitle: Collected Stories of Edna O’Brien

- Book 2 Biblio: Faber and Faber, $39.99 hb, 560 pp, 9780571270286

They present a welcome opportunity, then, these two new books from O’Brien’s new publisher, Faber and Faber – a chance for fresh discovery, for rereading Edna O’Brien. Literary fashion is cruel: when I went looking for O’Brien’s backlist in a bustling public library, The Country Girls had gone missing, and the last recorded borrowing date in O’Brien’s other works was a doleful 1988. I recalled a recent ABC interview in which Margaret Drabble remarked that being a woman writer was harder now than it had been in the 1960s and 1970s: harder to carve out a readership, harder to secure publishers’ ongoing attention, and harder to sustain a reputation.

During her long lifetime (she was born in 1930) O’Brien has been praised, patronised, excoriated, pigeonholed as a writer (‘novelettish’), and as a woman (‘skittish’, a ‘Mata Hari’). It hasn’t helped that she is beautiful (still), with an uncompromising presence and a commanding voice – every peaty syllable weighed and articulated. In a world where sexting has become a pernicious norm for teenagers, and priests are hauled before courts for molesting children, her books are unlikely now to be banned or even noticed for their sexual frankness. But as a writer she remains challenging, troubling, ruthlessly intelligent. She will never gather ‘Janeite’-style acolytes – her characters are too rebarbative – but, as these two new volumes attest, she continues to be stimulating, disconcerting, and immensely rewarding to read.

The stories selected in The Love Object represent her writing in the genre from 1968 to 2011. Chekhov has been her lodestar. The memoir (she was ‘reluctant’ to write it) is also a book of stories: ‘I tried to make each chapter, in a sense, as if t’were fiction, a story in itself.’ And so it is, a book of stories, life stories, conjured out of memory. O’Brien has long argued that writing comes through her, in a way. It is decidedly not the spiritualist’s automatic writing of Yeats’s wife, Georgie Hyde-Lees, but it is writing that has a hallmark of inevitability about it, even while so assiduously crafted.

‘ ... O’Brien has been praised, patronised, excoriated, pigeonholed as a writer (‘novelettish’), and as a woman (‘skittish’, a ‘Mata Hari’).’

‘It’s a very interesting thing about memory,’ she says in a television interview about Country Girl. ‘It is like a tap, or it’s like tapping a tree for rubber. Once you start tapping the old cells [she points at her brow], it comes, it comes. It’s like a whole influx of something that is stronger than memory. Of course it’s memory, but you’re back in it. You’re not writing it second hand.’ You can hear the performative grandeur of O’Brien in those words. It’s formidable, daunting, as is her lofty provocation about the visitations of memory: ‘Again, that accounts for a certain derangement: I do not call myself sane.’

This is the woman, the writer, who willingly took LSD with the Scots psychologist R.D. Laing (who afterwards charged her royally for the ‘consultation’), to immediate and devastating effect, but who nonetheless credits Laing with helping to shift her work to a deeper level. The memoir chapter ‘The Sleeve of Saskia’ gives the terrifying details and reveals O’Brien as a paradox: vulnerable yet given to danger, a woman who can’t swim and who, like her mother, is afraid of horses (and her father), yet who strikes out, again and again, into the ‘raw stuff’, which she also calls ‘the real stuff’.

Ireland gave her raw stuff in bucket-loads. A childhood of braided nature and ‘gnawing fear’, her father drunk, her loving Janus mother both nurturing and censuring. It also gave her a language (two, if you count Irish) of lyric texture, a culture of words, and enough trouble to freight her imagination for life. ‘It was borne in on me at that very young age that I came from a fierce people and that the wounds of history were very raw and vivid …’ (from the Memoir chapter ‘Visitors’).

Edna O’Brien

Edna O’Brien

(photograph by Joanne O’Brien)

You see her range and analytical intelligence in the chapter about her encounter with Gerry Adams and her visits to the North. For both she was castigated – by both sides, Catholic and Protestant. Her reactive anger is distinctive, a woman’s anger. About one lethal week in 1988 she writes: ‘It would need Dante, from down among the damned, to grasp the convolutions and repercussions of that week alone, cold murder, mad murders, hatred and revenge in all its sunken telluric depths. Poison and fear and funerals.’

About love and its aching fluctuations O’Brien is one of the master chroniclers. Her stories are almost exhausting in their evocation of passion, affection, jealousy, despair, and the toils of kinship. Read them slowly. Over time. And in the Memoir read beyond the sometimes hectic flourishes. The Edna O’Brien, friend of Jackie Kennedy and brief amour of Marlon Brando and Robert Mitchum, also knew the taste of bitter grounds and a writer’s ‘necessary’ isolation. Let her have her fond, as well as her bitter, memories.

It would be a taxonomic pedantry to divide the books. Characters recur in both; they shift and change names, but O’Brien is always writing to understand fundamentals. Her mother looms like a great Henry Moore sculpture, embracing, adamantine, but also a vulnerable woman with eyes of gentian blue.

‘A world made new by language.’ Heaney is right: O’Brien has that gift, an uncanny ability to give us back life with its sheen and with its abrasions. And from Joyce, she learned well where such lyrical precisions of noticing, the ‘lush descriptions of corpses and steers and pigs and kine, of sea and sea stones’, will lead: to ‘the extraordinary ascensions, in which worlds within worlds unfold’.

Comments powered by CComment