It is a hundred years since the publication of Howards End (one of only five novels by E.M. Forster to be published during his lifetime), and longer still, or so it seems, since Lytton Strachey, his fellow Apostle, entranced the Bloomsburys in the drawing room at 46 Gordon Square by daring to utter the word ‘semen’. Virginia Woolf dated modernity from that instant, such was its iconoclasm in Edwardian London.

Forster, born in 1879 – the same year as Vanessa Stephen, and two years before Virginia – was friendly with Bloomsbury but never fundamentally part of it. Leon Edel did not include him in his group biography, Bloomsbury: A House of Lions (1979), arguing that Forster’s life ‘did not become intertwined with the nine originals’. Michael Holroyd, in 1967 (coincidentally, the year when homosexuality was decriminalised in Britain), launched the Bloomsbury phenomenon with the first volume of his massive biography of Strachey. Victoria Glendinning, biographer of the tremulous and underestimated Leonard Woolf (2006), remarks that ‘The biography of Lytton made Bloomsbury sensational. It was a "hinge" publication, opening the way for the burgeoning Bloomsbury industry.’ It is a burgeon that has never drooped.

Quentin Bell’s respectful, elegant two-volume biography of his aunt, Virginia Woolf, appeared in 1972, soon followed by Nigel Nicolson’s Portrait of a Marriage (1973), an account of his bisexual parents’ risqué and rather likeable marriage. Frances Spalding, who visited Australia recently to deliver the Seymour Biography Lecture, contributed a biography of Vanessa Bell in 1983. Hermione Lee, in 1996, became just one of several biographers to offer a new reading of Virginia Woolf, Bloomsbury’s genius. Woolf’s own Diaries and Letters and inimitable Essays, published in countless volumes – and her husband’s excellent five-volume autobiography (1960–69) – told some readers more than they wanted to know about this voracious set.

E.M. Forster, in such company, would never shine. He was perhaps the least glamorous of major writers. Now, four decades after his death, with a new and rather testing biography of his own, his legacy seems to temper Bloomsbury – its self-absorption and exclusivity. Vis-à-vis those brilliant Elizabethan peacocks, Forster seems more modern, more democratic. His politics were instinctively libertarian. ‘Give a man power over other men,’ he wrote in a letter to Siegfried Sassoon in 1918, ‘and he deteriorates at once.’ ‘Only connect!’, Margaret Schlegel’s great (if misunderstood) ‘sermon’ in Howards End, may have become famous, but so too did one sentence in his essay ‘What I Believe’: ‘I hate the idea of causes, and if I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.’

Edward Morgan Forster’s childhood was privileged, but not always joyous. His father, an architect, died when he was two; his mother never remarried. He was predictably unhappy at school. When he was eight, his great-aunt Marianne Thornton (whom he would biographise in 1956, and who dubbed him The Important One) left him £8000 in trust, a large inheritance in 1887. It gave Forster security for the rest of his life, long before his books made him a second fortune.

Because of his languid posture, Forster always looks about five feet tall in photographs, but he reached six feet and had long, slender hands. He was shy, unfashionable, and thinly moustached. Strachey called him the ‘Taupe’, the French word for mole. He was amazingly naïve (‘not till I was 30 did I know exactly how male and female joined’). A respectable pianist, he was among the more musical writers and went on tackling Beethoven’s piano sonatas in old age. A serious Wagnerite, he attended many Ring Cycles as a young man. He collaborated with Britten and co-wrote the libretto for Billy Budd. He was better travelled than most of the Bloomsburys, more questing, venturing beyond Paris and Florence. He was a generous friend and, while never radical, a resolute supporter of liberal causes.

Forster, normally equable and modest (he reminded Christopher Isherwood of a Zen master), possessed a royal temper. There are interesting references in his notebooks to a series of hysterical ‘attacks’ when he was thwarted. Wendy Moffat, his new biographer, ignores these, but P.N. Furbank, her distinguished predecessor, is typically alert to them and quotes Forster: ‘Attacks take the form of sudden yelps, contortions, pretence fainting-fits, and the hitting of part of my body that don’t hurt against objects in the room that aren’t valuable …’

Forster’s relations with his mother, Lily – stout, gouty, rheumatic – were fond but claustrophobic, with resentments on both sides. He lived with her until her death in 1945. Once, when he cracked a vase, he was frightened to tell her and appalled by his ‘cowardice’. At the age of fifty-six he closed one letter, ‘Will now have some cocoa or an orange (not sure which!) and then go to bedy-by.’ Long after Lily’s death (which he genuinely mourned), he diagnosed some of their difficulties:

Now I am older I understand her depression better … I considered her much too much in a niggling way, and did not become the authoritative male who might have quietened her and cheered her up. When I look at the beauty of her face, even when old, I see that something different should have been done. We were a classic case.

Cambridge, in a sense, saved him. He relished his years at King’s College. In 1901 he was elected to its secret intellectual coterie, the Apostles. Other members included Maynard Keynes, Leonard Woolf, Roger Fry, Bertrand Russell, and their great influence, G.E. Moore. After a year’s travel in Italy with his mother – which provided the themes for two of his first three novels – he published his first short story in 1904. That year he confided: ‘I’m going to be a minority, if not a solitary, and I’d best make copy out of my position.’ His first three novels followed quickly: Where Angels Fear to Tread (1905), The Longest Journey (1907), and A Room with a View (1908). Wendy Moffat is quite uninterested in the intricacies of publishing history. Her Forster achieves prominence and critical renown in a kind of blur; the books seem to be published of their own accord. Furbank is much more thorough. Even Frank Kermode, in his short, late book, Concerning E.M. Forster (2009), fills the gap with an account of the early books’ warm reception.

With the publication of Howards End in 1910, Forster’s sales and reputation soared. For some, it is a more successful novel than the widely fancied A Passage to India (1924), with its mystical flights and editorial lacunae. Late in life, Forster himself described Howards End as ‘my best novel and approaching a good novel’. The story of the half-German Schlegel siblings and their vicissitudes is Hardy-like in its fatalism and wilful melodrama (Forster was an admirer of Hardy). The second half of the novel, with its successive hammer blows, is inspired. The most political of Forster’s works, it deals with power and ownership, and the fragility of both: ‘the inner darkness in high places that comes with a commercial age.’ All three Schlegel siblings – Margaret, Helen, and Tibby – possess a kind of quirky vividness and individuality that is missing in the strangely unrealised characterisations of A Passage to India, the last novel to be published in Forster’s lifetime. Tibby, the younger brother – witty, frigid, indifferent – is one of Forster’s most acute creations.

In 1912, wealthier than ever and a literary celebrity, Forster sailed for India, mainly to visit Syed Ross Masood, a tantalising young man from Delhi whom he had tutored in England. Masood – ten years younger than Forster – was the scion of an influential Anglicised Muslim family which had moved between the two countries. Moffat, laying it on, describes Masood as ‘profoundly handsome, in a matinée idol exotic sort of way’. Masood liked to tease Forster, psychologically and physically. Easily bored, he would turn Forster upside down and tickle him. The effect on Forster, after years of cautious affection, was one of growing frustration. Yet he never forgot Masood: ‘There was never anyone like him and there never will be anyone like him.’

En route to India, Forster had an encounter that may have been more influential than his biographers have realised. Kenneth Searight, a declared pederast with what Moffat describes as a ‘Byronic sensibility’, was an officer in the Indian army. On the P&O liner he showed Forster his manuscript titled Paidikion (the book of boyhood), a florid, 600-page catalogue (sometimes in autobiographical verse) of his myriad and versatile encounters with Indian boys. Forster was fascinated by this sexual paean, and by its forthright author. One evening the officers danced under the stars, ‘Searight commandeering Morgan into a foxtrot’, as Moffat notes. They never saw each other again. (Searight, in retirement, went on to construct a universal language called Sona, which still has its champions.)

Furbank and Moffat both mention this shipboard meeting, but may have overlooked Searight’s profound influence on the novelist. Ronald Hyam, the Cambridge historian, writes about Searight in an absorbing chapter entitled ‘Greek Love in British India’, which appears in his new book, Understanding the British Empire (2010). Hyam argues that homosexual behaviour by British men in India was much more prevalent, much more varied, much more audacious, than previous historians have suggested, and that the risks involved in interracial homosexuality were minimal. One contemporary of Searight’s suggested in his own memoir that ‘pricks were as plentiful as lollipops – if you knew where to look’

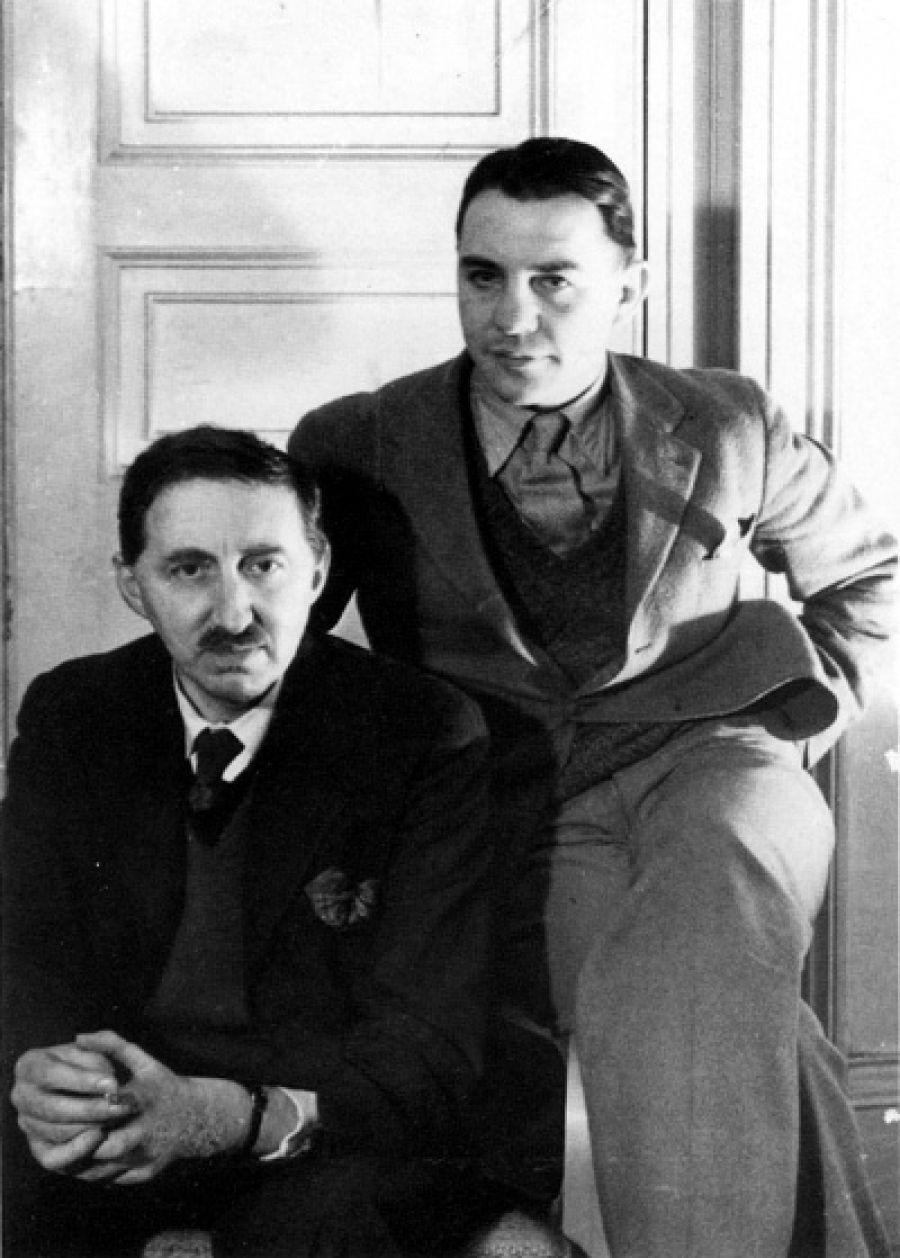

Morgan, age three, and his mother, 1882

Morgan, age three, and his mother, 1882

Hyam goes on to suggest that Searight’s creative influence on Forster may have been considerable: ‘Forster was certainly shaken up by their encounter, and began writing more definitely about homosexual themes.’ We know that Forster suspended work on A Passage to India and began writing Maurice, his only homosexual novel. Forster himself stated that the donnée occurred when George Merrill – boyfriend of the famous socialist and homosexual activist Edward Carpenter – made a pass at him, touching a creative spring ‘just above the buttocks’: ‘It was as much psychological as physical. It seemed to go straight through the small of my back into my ideas, without involving my thoughts.’

The history of that short novel (dedicated ‘to a happier year’) is well known. Forster went on revising it for decades, determined to give the tale a happy ending, not the usual suicidal or murderous one. But he refused to publish it while he was alive. To his great confidante Florence Barger he wrote: ‘it is unpublishable until my death and England’s.’ Among homosexual friends the manuscript circulated widely but furtively; it was a kind of rite of passage for new acquaintances. When the young Christopher Isherwood admired it in 1932, Forster kissed him on the cheek. Another friend, urging Forster to publish it, cited the example of André Gide, author of L’Immoraliste (1902). Forster rejoined, ‘But Gide hasn’t got a mother.’ Even after Lily’s death, Forster was not willing to run the risk of hurting his friends. When Isherwood urged him to relent he said, ‘I am ashamed at shirking publication but the objections are formidable.’ Privately he wondered, ‘Publishable? But worth it?’

Throughout his life, Forster railed in private about the bigotry and stupidity of British attitudes towards homosexuality. ‘When I am 85 how annoyed I am with Society for wasting my time by making homosexuality criminal. The subterfuges, the self-consciousness that might have been avoided.’ He blamed his fictional blockage of five decades on this institutionalised homophobia. ‘I should have been a more famous writer if I had written or published more, but sex has prevented the latter.’ After belatedly finishing A Passage to India in 1923, he told Sassoon in a letter: ‘I shall never write another novel after it – my patience with ordinary [for which we can read heterosexual] people has given out.’While Moffat is only interested in this sexual impasse, Furbank speculates about two other possible constraints: first, that Forster was ‘of the type defined by Freud as "Those wrecked by success": that he was one of those who, on realizing their dearest wishes, are afflicted and inhibited by superstitious fears – the fears in his case taking the form of a conviction of sterility’; second, the starker possibility that he only ever had one novel to write.

Maurice, which was finally published in 1971, is widely regarded as one of the slightest novels ever written by a major author. The brief chapters certainly unbalance the book, and Forster’s class consciousness has never been more plangent. As in all of his work, some passages are cringe-making: ‘He loved men and always had. He longed to embrace them and to mingle his being with theirs’; and ‘If Maurice made love it was Clive who preserved it, and caused its rivers to water the garden.’ They remind us of Lionel Trilling’s sense of Forster’s limitations. Trilling, his first major critic; spoke of Forster’s ‘refusal to be great’. Yet the plot in Maurice is not without interest, and stolid, snobbish Maurice Hall (‘an outlaw in disguise’) ultimately makes personal choices that would have shocked Forster’s earlier characters. Moffat calls it his only ‘truly honest’ novel (whatever that means), while David Leavitt, in the current Penguin edition, makes a case for its being deemed ‘wise, ferocious and beautiful’.

Forster’s travels continued during the Great War. In late 1915 he sailed to Alexandria as a Red Cross volunteer; he was the Searcher in the Wounded and Missing Department. By the sea at Montazah, among the naked bathers, he sensed a world of sexual opportunity and celebration. ‘Why not more of this? Why not? What would it injure? Why not a world like this?’ he wrote to his great friend Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson. One evening he returned and finally, at the age of thirty-seven, had sex with a man.

He also met Constantine Cavafy, whose incomparable poetry he would devotedly introduce to the rest of the world. Cavafy – fifty-four, vain, fastidious, living above a male brothel in a flat without electricity – worked fitfully as a clerk in the Third Circle of Irrigation. He was at home every evening between five and seven, and through him Forster was introduced to a very different kind of homosexual milieu. How far he had travelled from King’s College and Garsington. Forster would always regard this meeting as one of the great boons of his life.One evening he boarded a tram and bought a ticket from an insouciant young Egyptian with good English. Mohammed el Adl was approximately seventeen, proud, charming, ambitious. Their furtive, passionate affair only ended with Forster’s return to England. Terminally ill with consumption, Mohammed wrote to Forster: ‘My compliments to mother. My love to you … Do not forget your ever friend.’ And he didn’t. Forster always preserved the ticket stub from their first meeting.In 1921 Forster revisited India to work as the secretary to the Maharajah of Dewas State Senior. No homosexual himself, the Maharajah tolerated his secretary’s private life, with one condition: that it did not involve sexual passivity. For perhaps the only time in his life, Forster sodomised the available boy and was surprised by his own sadistic potential:

I resumed sexual intercourse with him, but it was now mixed with the desire to inflict pain … it was bad for me, and new in me … I wasn’t trying to punish him – I knew his silly little soul was incurable. I just felt he was a slave, without rights, and I a despot whom no one could call to account.

At which point Wendy Moffat primly rallies: ‘With a clinical eye Morgan watched his own complicity in the privileges of race and caste.’

In 1922 Forster returned to England via Port Said, where Mohammed el Adl was dying. Soon after, Virginia Woolf met him on the street in London and was shocked by his dismal, lovesick appearance. With ‘her usual fine asperity’ (Edel’s phrase) she noted in her diary, ‘The middle age of buggers is not to be contemplated without horror.’ Woolf confessed to being ‘flustered’ by Forster, and went on sketching him in diaries and letters. Acid and frigid as ever, she wrote to Vanessa: ‘he is limp and damp and milder than the breath of cow.’ Again, Edel strikes the right note: ‘The art of verbal murder runs deep in England.’

Odd though it seems, Forster was considerably bolder than Woolf ever dared to be. She just didn’t know about it, because Forster never trusted her enough to confide in her. ‘One waited for her to snap,’ he once said.

Not that Woolf ever underestimated the author of those five bestselling novels. When Forster told the members of the Memoir Club how fond he was of them, Woolf confided to her diary that she almost wept. They craved each other’s approbation and never quite got enough. Hurts both minor and major occurred over the decades. They barely avoided a serious quarrel in 1927 when Woolf, reviewing Aspects of the Novel (1927), said, ‘We want to make Mr Forster stand and deliver … We feel that something has failed us.’ Forster’s tribute, when Woolf committed suicide in 1941, was surprisingly measured. Striking here is the Bloomsburys’ willingness to review one another, though they were intimate friends and colleagues. This preparedness to judge each other, by no means always glowingly, is not a feature of contemporary literary cultures, where a certain coyness often prevails.

Forster’s other great – rivalry is the only word for it – was with D.H. Lawrence, whose early novels he especially admired. They met in 1915; Forster visited the Lawrences in Sussex soon after. (Furbank deals with this at length; Moffat only in passing.) The three-day visit began well, but Lawrence was soon at his most denunciatory and imperceptive, goading Forster to change his way of living. To Bertrand Russell, Lawrence wrote: ‘he sucks his dummy – you know, those child’s comforters – long after his age … Why can’t he take a woman and fight clear to his own basic, primal being.’ Bitter letters followed, and the unlikely friendship waned, though not their mutual regard. Cryptically, Lawrence wrote to Forster: ‘To me you are the last English-man. And I am the one after that.’ When Lawrence died in 1930, Forster, irate at the obituarists’ meanness and derision, published his own tribute to ‘the greatest imaginative novelist of his generation’. T.S. Eliot, typically dry and captious, disputed this in print, occasioning one of Forster’s finest rejoinders:

Mr Eliot duly entangles me in his web. He asks what exactly I mean by ‘greatest’, ‘imaginative’ and ‘novelist’ and I cannot say. Worse still, I cannot even say what ‘exactly’ means – only that there are occasions when I would rather be a fly than a spider, and the death of D.H. Lawrence is one of these.

(‘Here,’ Frank Kermode remarks, ‘is an occasion for Forster’s audience to stand and applaud.’)

As the fiction dropped away (his short stories, often written for his own titillation, remained unpublished during his lifetime), criticism became more important in Forster’s life. In 1927 he delivered the Clark Lectures at Trinity College, which were published as Aspects of the Novel. F.R. Leavis sat through all eight lectures and was ‘astonished at the intellectual nullity that characterised them’. Even Kermode, a lifelong admirer, admits that Forster had his blind spots: chiefly Ford Madox Ford and James Joyce, and V.S. Naipaul and Graham Greene in later years. Kermode is troubled by Forster’s ‘long guerrilla action’ against Henry James. Forster was unremitting in his attacks on James’s purist sense of fiction’s responsibilities. ‘There is no such thing as the art of fiction,’ Forster declared. He insisted on the novelist’s right to omniscience (even stooping to ‘dear reader’ on occasion). James’s insistence on a single point of view bored, or possibly tested, him. Lamely, he even suggested that there was ‘no savour in any dish of Henry James … Maimed creatures can alone breathe in his pages.’ (Moffat is an all too willing acolyte; in a risible lapse, she accuses James of lacking a sense of humour.)

Forster’s difficulty with Henry James may have begun at their first meeting, in 1908. The younger novelist visited James in Rye. The Master, aged sixty-eight, mistook him for G.E. Moore, his fellow Apostle, and Forster was too polite to correct him. It was an awkwardness that Forster clearly never forgot.

In his essays and his many broadcasts for the BBC (some of which have been preserved in The BBC Talks of E.M. Forster 1929–1960: A Selected Edition, 2008), Forster was a lucid guide, if not always an exhilarating one. He spoke up for what he believed, and defended a particular ideal of critical exchange. The following passage, from his essay on T.S. Eliot, would be pilloried today, and its author accused of élitism:

Mr Eliot does not write for the lazy, the stupid, or the gross. Literature is to him a serious affair, and criticism not less serious than creation, though severely to be distinguished from it. A reader who cannot rise to his level, and who opens a book as he would open a cigarette case, cannot expect to get very far.

After his adventures in Egypt and India, Forster became sexually active and rather more daring than we had realised. He was conscious of the perils, the risk of entrapment, and came close to being blackmailed and exposed a few times. His preference was for working-class men: policemen, pugilists, former prisoners. He wrote in his diary, ‘I want to love a young man of the lower classes, and be loved by him and even hurt by him. That is my ticket …’

This led him in 1930 to a personable policeman named Bob Buckingham, who was twenty-five years his junior. Their long affair, however unconventional, was tender and emphatic, though Buckingham equivocated about its profundity after Forster’s death. He was undoubtedly the great love of Forster’s life. The writer endured Buckingham’s bisexuality and acted as witness when he married May Hockey in 1932, the year of Forster’s major prostate surgery. Their ménage à trois was known to all their friends. Forster spent all his weekends with the Buckinghams. He adored their son, Robert Morgan (known as ‘Robin’), to whom he stood godfather. Always generous with friends and lovers, Forster supported the Buckinghams (one gift in the 1960s amounted to £10,000, a small fortune then). Especially intriguing was Forster’s growing fondness for May, whom he called ‘Darling’ in one letter. Alan Bennett could do something fascinating with an eccentric bond like that.

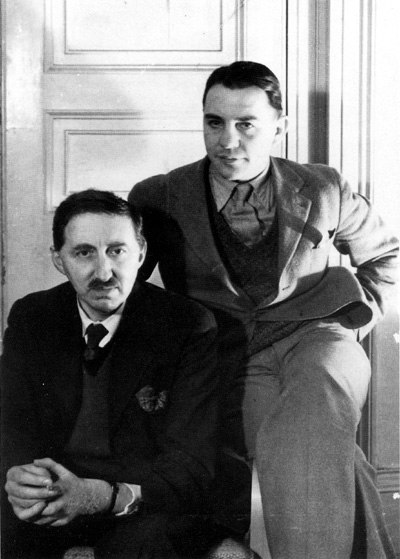

Morgan and Bob Buckingham, c.1934

Morgan and Bob Buckingham, c.1934

Forster’s frequent travels with Bob took them to the United States in 1949. During their extended stay they met the newly famous Dr Kinsey. Forster’s renown was by then immense. When he lectured on ‘Art for Art’s Sake’ in New York, the audience included William Faulkner, Thomas Mann, John Steinbeck, Christopher Isherwood and his old friend W.H. Auden, whom he had never judged for leaving England before the war.

That same year, Forster declined the knighthood that Clement Attlee offered him. Slyly preferring gongs that appeared after one’s surname, he accepted the Companion of Honour, which is in the monarch’s gift. He enjoyed meeting the queen and remarked that had she been a boy he would have fallen in love with her. For her part, the queen told him that it was a shame that he hadn’t published a book for so long. In 1969 she topped up his honours with the Order of Merit.

In old age, Forster’s reputation for sagacity and humanity was secure. Kermode – himself lauded and indefatigable until his recent death, aged ninety – is droll on the subject of Forster’s late popularity: ‘He lived to be old and still active, an achievement that almost always impresses the public.’ He donated money to the cause of homosexual law reform and met Wolfenden, author of the report that would lead, belatedly, to liberalisation. He testified on behalf of the author in the Lady Chatterley’s Lover case, though afterwards, ever alert to artistic vanity, he asked his friend J.R. Ackerly: ‘By the way, did D.H. Lawrence ever do anything for anybody?’

After his mother’s death, Forster spent his last twenty-five years living in King’s College. As a Fellow of the College, he was accessible, liked, and unpretentious. He cultivated students, especially the sons of farmers and miners. One of his protégés was P.N. Furbank, whom he ultimately appointed his official biographer, which disappointed his original choice, William Plomer. Furbank, drawing on his own notebooks, closes his biography with a brilliant portrait of the elderly Forster.

Forster, in old age, was almost shocked by his abiding libidinousness. In 1960 he wrote to Ackerly: ‘I am rather prone to senile lechery just now – want to touch the right person in the right place, to shake off bodily loneliness … Licentious scribblings help, and though they are probably fatuous I am never ashamed of them.’

In her psychosexual biography, Moffat makes eager use of entries from Forster’s diaries that have just been released. She thanks Furbank for sharing unpublished documents and audiotapes with her, but any comparison with Furbank is invidious, on many levels: stylistic, interpretative, scholarly. Moffat is merely conforming to the prevailing desire among publishers for social history and erotic biography. Not that she hasn’t been in good hands: in the acknowledgments she thanks the noted American publisher Jonathan Galassi for editing the manuscript ‘with the grace and patience of a Zen master’. Clearly a devotee, Moffat ends the book with a ringing endorsement of her subject: ‘So great and honest a writer and so humane a man.’ But the biography is prurient, slangy, and at times tendentious. Moffat’s relentless emphasis on the erotic reminds us of a passage in Daniel Mendelsohn’s recent review of Edmund White’s lamentable new memoir, City Boy:

a biography … that lost sight of the fact that sex and sexuality (or religion, or race) are, finally, part but not whole of our lives – there are other influences, other forces at work that help shape the creative mind, indeed any mind – risks devolving into pat chauvinism. (New York Review of Books, 30 September 2010)

But what of Forster himself, that sparing and intensely ambitious artist? What of those Edwardian novels of class, and ‘six-hundred-pounders’, and social estrangement? Re-examined in the light of the new biography and Frank Kermode’s superb, elegiac tribute, Forster becomes more complex, more curious. His flaws remain apparent – the mystical flights, the abrupt transitions, the wooden characters, the lazy indifference to anyone outside his social ken (principally, Leonard Bast in Howards End). Of all the major writers he is perhaps the least mellifluous. He never wrote anything as lyrical as To the Lighthouse or as original as The Waves, and he had none of the poetry that he rightly attributed to Lytton Strachey. Somewhere in Howards End he halts and writes: ‘A word on their origin’; later he ponders, ‘Why has not England a great mythology?’ It is impossible to imagine Faulkner or Woolf writing stuff like that. In A Passage to India the prose seems especially laboured and angular, almost like notes for a novel: ‘Although her hard schoolmistressy manner remained, she was no longer examining life, but being examined by it; she had become a real person.’

Somehow, though, his intense, brittle plots survive these imperfections. It was a particular kind of realism, never deceived by social veneers. As the narrator says in A Passage to India, ‘One can tip too much as well as too little, indeed the coin that buys the exact truth has not yet been minted.’ Forster’s characters are impressively weird, especially Adela Quested (almost as twisted as her name) and the bizarre Schlegels. Only Muriel Spark’s women were weirder. If some of his characters never quite chime, especially in A Passage to India, they collapse or torment themselves in renewably modern ways. Chief among these is Helen Schlegel, with her bass note of ‘panic and emptiness’. Then there is her sister, Margaret, who becomes extraordinary when she discovers that her fiancé betrayed his first wife (her benefactress) with a prostitute: ‘Only connect! That was the whole of her sermon. Only connect the prose and the passion …’

Forty years after his death at the age of ninety, and a century after his prime, E.M. Forster again intrigues and evades the reader. For Maynard Keynes, he was ‘the elusive colt of a dark horse’. Even Virginia Woolf said this of Forster in her 1922 diary: ‘I am impressed by his complete modesty … There is something too simple about him – for a writer, perhaps, mystic, silly, but with a child’s insight; oh yes, & something manly and definite.’

Forster may not loom at us like the Oscar Wilde of Richard Ellmann’s bravura peroration (‘a towering figure, laughing and weeping, with parables and paradoxes, so generous, so amusing, and so right’), but in a franker contemporary light Forster seems pertinent, more attuned than most to the toxins of repression, richly changed by life’s contingencies, and, yes, oddly dashing.

Books mentioned in this article:

Leon Edel, Bloomsbury: A House of Lions, Hogarth House, 1979

P.N. Furbank, E.M. Forster: A Life, Secker & Warburg, 1977

Ronald Hyam, Understanding the British Empire, OUP, 2010

Frank Kermode, Concerning E.M. Forster, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2009

Mary Lago, Linda K. Hughes, and Elizabeth Macleod Walls (eds), The BBC Talks of E.M. Forster 1929–1960: A Selected Edition, University of Missouri Press, 2008

Wendy Moffat, E.M. Forster: A New Life, Bloomsbury, 2010

Lionel Trilling, E.M. Forster: A Study, New Directions Books, 1943