- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Pack the overnighter, put on the black dress – she wears it like a skin – kiss the kids, grab the wheel, don’t let go until back home. So Hetti Perkins begins ‘Home + Away’, the title of the first program of her recent television series, art + soul, and also the first chapter of the accompanying book.

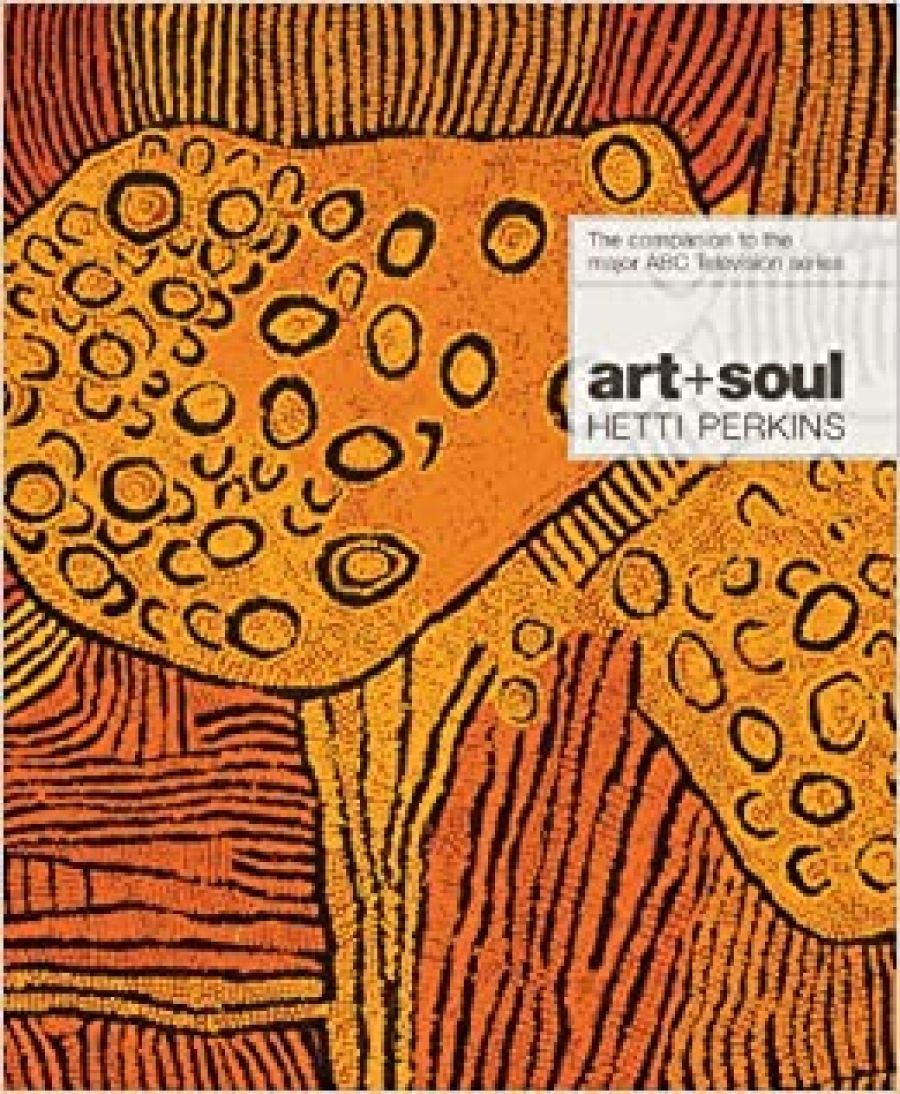

- Book 1 Title: art + soul

- Book 1 Subtitle: A journey into the world of Aboriginal art

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $89.99 hb, 305 pp

First stop is Mparntwe (Alice Springs), which is Hetti’s ancestral home. She has family buried in the same cemetery as Albert Namatjira. At journey’s end, we realise that Hetti has never been away but has taken us through the many rooms of her large home, her Aboriginal art world.

Despite constituting only three per cent of the population, today Aboriginal voices are being heard everywhere. Whatever their differences, they generally echo a shared cultural perspective. It can seem a narrow perspective, since their many stories are nearly always about things Aboriginal. However, this restricted horizon is not confining. Like the TARDIS, the Aboriginal world is much bigger inside than it seems from the outside. Their stories are not xenophobic or narcissistic, but reflect a world view seen from the inside, as if the world is in the body rather than the body in the world. If this world view is necessarily highly subjective and often autobiographical, it is not egocentric or self-indulgent, but a lens through which the world is known. A typical example is Charlie Perkins’s A Bastard Like Me (1975). art + soul is another. Hetti might never let us forget that she is Charlie’s daughter, but she stakes her own ground. No white experts are wheeled in to set us straight. This is Hetti’s world.

While this approach makes for good television, as her presence can carry the emotive content of the story, it is less suited to the silent disembodied space of the book. art + soul, a well-written, large-format, and beautifully illustrated production, has additional interesting information, but it is an adjunct to the television series, rather than an autonomous text. How, then, does Hetti stack up as a performer?

She does not have the sartorial panache of Robert Hughes, nor his forensic wit or way with words, but she does share his appetite for metaphor and cliché and the ability to lend their sometimes dubious content an unquestionable certitude through the singular presence of person. Hetti’s person gains its authority from her Aboriginality, which she constantly foregrounds as a proud, heroic, and archetypal Australian identity. In this respect, art + soul is a land claim. Hetti’s second magic ingredient is her warm hospitality. She has Betty Churcher’s relaxed charm, rather than Hughes’s nervy belligerence.

art + soul will be criticised for being too personal and uncritical. It does not have the razor-edged sardonic wit of John Mundine or Marcia Langton. However, such expectation misses its achievement. The easy rapport between Hetti and her subjects produces a sort of phenomenological rather than disembodied bird’s-eye view of art history that is the conventional space of critical inquiry. This affect is particularly powerful in the television series, which makes Hetti’s black iconic silhouette into an unfailing lucky charm that unlocks the Aboriginal art world. On the cover of the book, it Mona Lisa-like holds our attention. By the end of the television series, it has become a familiar talisman – so familiar that, like a good parent, and indeed like her father, Hetti can get away with lecturing us on some home truths about the ‘settlement’ of her place.

Hetti’s gift for telling stories is the lifeblood of art + soul. Traditional story-tellers make themselves an implicit part of the narrative but also make us, the listeners, feel we are there as well. It is the secret to Hetti’s hospitality: she makes us feel part of the story. It is not always a pretty or profound story, but it is true and is told from the heart. The title, art + soul, delivers.Many stories are told, and Hetti is always milking her friends for more. The book features twenty interviews with artists, each a story with its own charm. Here, art seems a very everyday thing, even when the stories inexplicably shift into a mythic dimension. The old artists in far-off places must be descendants of Homer or Moses, as they speak in the austere Old Testament manner affected by Ancestral Beings. Their stories are like a Poussin painting: every action and thing has pared-down heroic qualities, a freedom, unfamiliar to us, carved from the grip of fate. Perhaps this is where Charlie Perkins got his gift for the aphoristic homily, which Hetti never quite matches.

Hetti’s greatest achievement as a storyteller is to seamlessly weave very different art-school practices – Pintupi, Gija, Yolngu, Tiwi, Kuninjku, and an equal variety of urban traditions – into one overarching story. The glue is politics. Art and politics are usually ill-matched bedfellows. Hetti makes their marriage seem quite easy because her focus is not art that is about politics but her own motivations, in which politics is the horizon of her being, shaping its every thought and move. For her, the Aboriginal contemporary art movement is essentially a political enterprise.

I loved every minute of the television series and book, even when I groaned at some of the clichés. I groaned the loudest when Hetti said that Albert Namatjira was ‘lost between worlds’. Why do such tired assimilationist clichés still have currency? If Namatjira was lost between worlds, he is the only artist in art + soul who didn’t know his way. It seems to me that Namatjira was never lost between worlds, but was done over by the politics of one of them.

At the journey’s end, three weeks and thousands of kilometres later, Hetti walks back in the door with the kids surging towards her for hugs and kisses. Another clichéd moment, but art + soul was always going to have a happy ending, for it is, at heart, about family. This is why names have from beginning to end been very important. Places are invariably given their Aboriginal (not European) names, as if great swathes of the continent are a different country. People are also carefully named. They are generally introduced on a first-name basis, sometimes by their skin name. It is a matter of etiquette. art + soul is, at a deep level, a lesson in manners, in how to relate properly to others. To get the full soul experience, I recommend watching the television series and reading the book in tandem, with friends and family at home.

Comments powered by CComment