Melbourne, which has somehow appropriated for itself the reputation of being the first Australian city of ‘thought’, has become the last major city in this country to host a large-scale writer’s week. Well, we now have one and it’s called the Melbourne Writers’ Festival, and it is currently being staged.

The Festival’s major attractions have been concentrated into a three-day read-in and talk-in. from October 3rd–5th, at the grand old theatrical premises of The Athenaeum in Collins Street. It’s a wonderful spot, complete with an old-style library (one with books) and the modest splendour of an earlier time, which somehow suits the aura of an event such as a writers’ festival.

How it came about that Melbourne was the last capital to stage a writers’ week is a myth lost in the veils of time, as we writers refer to badly documented historical areas. Certainly, when the Spoleto Festival began to crystallise as an event, the notion of a writers’ event began to take shape.

Initially, the idea was to approach a couple of noted overseas writers to appear as guests of Spoleto. I guess that before this idea of a writer’s festival was probably booted around by various groups; I know that within the Melbourne City Council there hid also been ideas floated, as they say in Yes, Minister land, about a festival along the lines of Writers’ Week at the Adelaide Festival of Arts. Cliff Smythe, the Writer in the Community for the Council, had written a letter to John Pinder, Chairman of the MCC Cultural Advisory Board, about the ways in which the MCC could assist with the idea of a writer’s week.

We all had a conference when it was realised that many groups were now thinking along the same lines: Mark Rubbo convened an initial meeting, at the Victorian Ministry for the Arts, of such interested people as Mary Lord from the National Book Council, Helen Garner from the Literature Board, Jennifer Ellison from the Ministry for the Arts, literary agent Caroline Lurie, Scripsi editors Peter Craven and Michael Heyward; and Spoleto management.

That meeting realised that if the Festival was, to occur, Spoleto time would be the only appropriate moment this year. A committee was formed, an official sub-committee of the Victorian Branch of the National Book Council, with Mark Rubbo as chairperson. We realised that what we were terribly short of, as regards a writers’ festival was

- Money

- Writers

- A venue

- Everything Else

Time was running out, as they say in the best and the worst novels. Quickly we prepared a budget, secured the Athenaeum Theatre complex as a venue, began compiling lists of writers local and overseas, and applied for funds to the Literature Board the MCC, and the Victorian Ministry for the Arts. The bad news was that it was May, towards the end of the fiscal year, and everybody was out of money; also, it was May, and we had to get money for, and agreement from, overseas guests in time for them to arrive by late September. The good news was that everyone was keen to see Melbourne have a writers’ festival.

The Premier’s Literary Awards were being held in the month of Spoleto, and it was obvious that the awards should be a central part of the festivities. A problem appeared when it was discovered that our festival, if timed around the Premier’s Awards would be in direct competition with the Warana Writers’ Week in Brisbane. We debated all sorts of things, like intersatellite hook-ups with Brisbane (well, l debated that). So we agreed to put it off for a week, into mid-Spoleto … when it just so happened that the VFL grand final was on, and we all knew of so many writers who would be unable to tear themselves away from the fortunes of the football as it was hurled about the MCG on that one day in September that we had to move the festival on another week, if the Premier’s Awards people would agree to delaying. And they did.

Now it was down to the talent. We drew up lists of Victorian, interstate, and overseas writers; from this copious grab bag we constructed a form of short list on which various compromises were reached, influenced by such constraints as finance; the number of people on the committee who had either (a) heard of, (b) liked or (c) would tolerate the writer’s work and the accessibility of the writer’s work – that is to say, not too accessible, for that would constitute cheap penny thrillers and light romance (the sort of thing I write); and not too avantgarde, because no-one would like it or understand it (the sort of thing I write). The people we finally chose are, we think, representative of writing in Australia now. The overseas guests are English poet Christopher Logue and New York poet John Ashbery.

The committee then spent hours and hours proposing particular writers for particular topics, and Kate Ahearne from the National Book Council spent hours and hours confirming the matter with writers around Australia. And the Writers’ Festival program was the result. As well as the highlight of the Premier’s Literary Awards dinner, at which the winners will be announced the program includes readings at Mietta’s, in trams, and at the Athenaeum; a Writers’ Festival of Films at the State Film Centre; the launchings of new books by Elizabeth Jolley and Janine Burke; and panel discussions including ‘Why I Write What I Write’, ‘Political Perspectives’, and ‘What’s the Point of Critics?’ Apart from those already mentioned, writers taking part in these events include Helen Gamer, Frank Moorhouse, Angelo Loukakis, Jim Davidson, Don Watson, Christopher Koch, Georgia Savage, Peter Mathers, Kevin Hart, and many others.

And yes, we got our money. The Literature Board allocated $6,000, the Victorian Ministry for the Arts $9,000 (and for our sins we were so desperate for funds we petitioned Race Matthews, the minister, directly for assistance) and the Melbourne City Council gave us a grant of $6,350. The Spoleto Festival, with which we have a kind of non-Orwellian Big Brother relationship, allocated about $10,000, to cover the costs of freighting the two OS poets and accommodating them in pleasant Melbourne surrounds. The Melbourne Writers’ Festival had also decided to seek assistance from Australian printers, publishers and booksellers, and we sent a sort of begging letter asking for help. The response was big; with replies and cheques amounting to several thousand dollars. The thoughtful groups who donated money to the Festival are Angus and Robertson, Hill of Content, Greenhouse Publications, Heinemann Australia, Melbourne University Press, Pan Books, Macmillan, Readings Bookshops, Schwartz Publishing, Anne O’Donovan Pty Ltd, D.W. Thorpe, McPhee Gribble, The Five Mile Press, Gordon and Gotch, Penguin Books Australia, J.M. Dent, Robert Anderson and Associates, Ian Templeman, Methuen, University of Queensland Press, Oxford University Press, Transworld (Corgi-Bantam) and Griffin Press. This great contribution has made it possible for the Festival to be properly organised, for the writers and their readers.

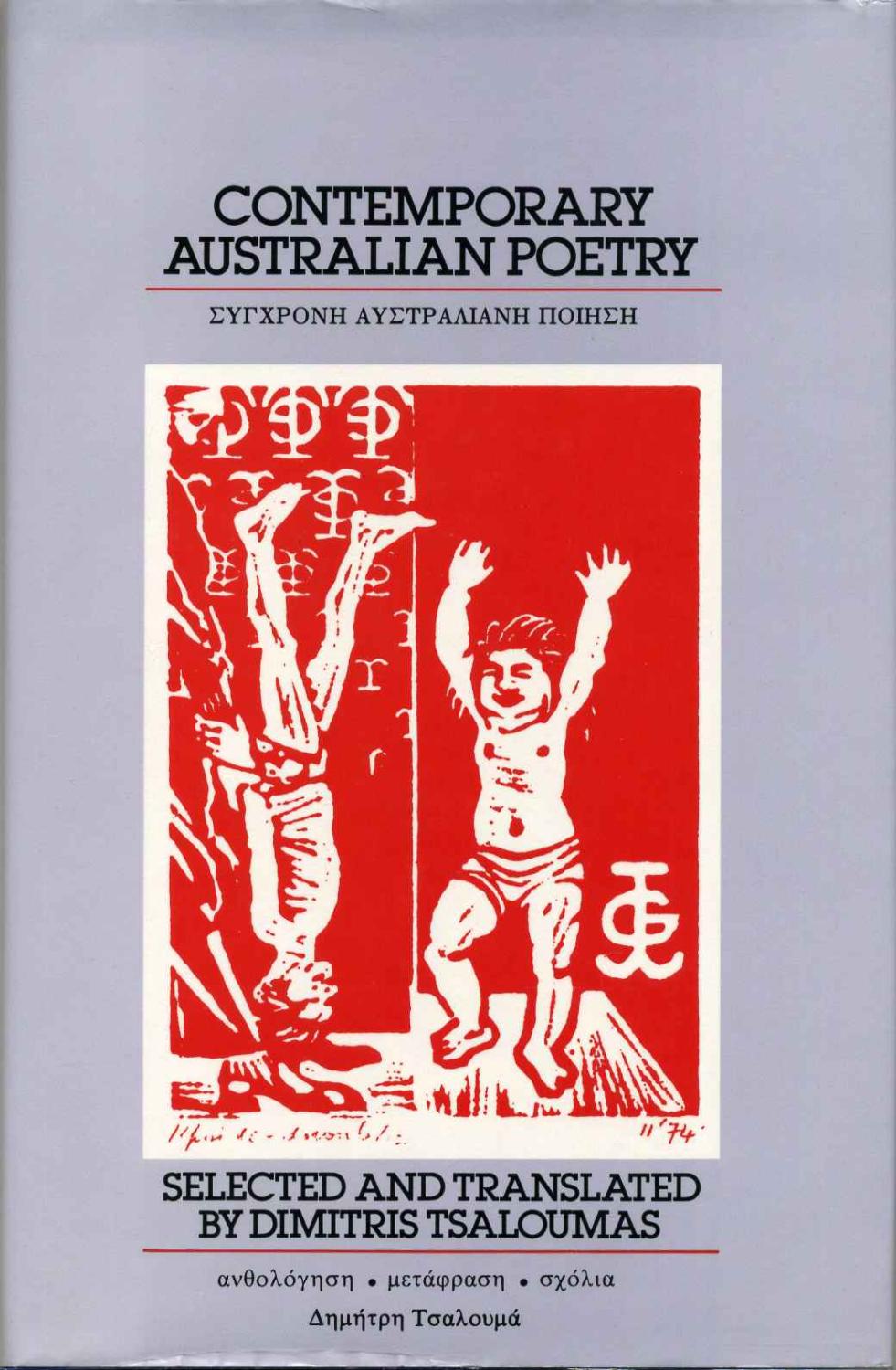

More help came from Piccolo Spoleto, the local multicultural arm of Spoleto, who gave us assistance – as did Australia Airlines (whom I still call TAA sometimes) who donated the airfares – to bring down from Sydney two writers not as Anglo-Celtic as most, Angelo Loukakis and Rosa Cappiello. This highlighted another dilemma. We wanted the festival, particularly since it was amidst the Spoleto Festival of Three Worlds, to be multi-cultural. Endlessly the committee ranted on to itself about multiculturalism and how to do it. We wanted it, but the committee and the writers themselves thought it inappropriate to have an ‘ethnic section’. Shouldn’t we just make sure we had a balance of various cultures and writing forms. rather than ‘ghettoise’ any of the writing’? We agreed to forget the heading and go with the concept; to have writing first, and background after.

Of course, the committee had to pay mind to the numbers of boy writers and girl writers being invited, and poets versus novelists, and scriptwriters versus prose writers and so on. But generally, you’ll find all the poets reading together, so some sacred boundaries are yet to be broken as we tear down the walls of difference around town.

What else to say? I have been employed as a co-ordinator, and in tandem with the Spoleto gang of Mark Worner, Rosie Hinde, Wendy Forster, and Kate Deling, along with the NBC’s Kate, Mary and Enid, and the great contribution of the volunteer committee already enumerated, we have managed to stumble to this point.

The work yet to come will be the festival itself; for it is the talent, the writing, which is what it’s all about. That, and that the people who come to taste the offerings have a good time. Some writers are giving up work time, some are coming from a long way away for not much pay.

This raises a good point. The committee, splendidly I thought, decided that all writers would be paid the same performance fee. Whether world-famous mega-novelist or unknown street poet, whether critic or writer of the TV soap, all would get $50 a spot – maybe more if the budget stretches. It’s not a lot, so you will appreciate the commitment these writers have to writing and readers. We made most of the readings free, to reward the reader for having bought the book, so to speak.

I could write about the content of the Festival, what the writers will read or talk about; but I feel they are eminently qualified to do that, better than I. And writers’ festivals happen so that the reader can attend firsthand, break through the word on the printed page, burst through that trompe of the eye, past my callow praise, and straight into the foyer of the Athenaeum itself, to put a face and voice to the words.