- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Flower and the Word

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

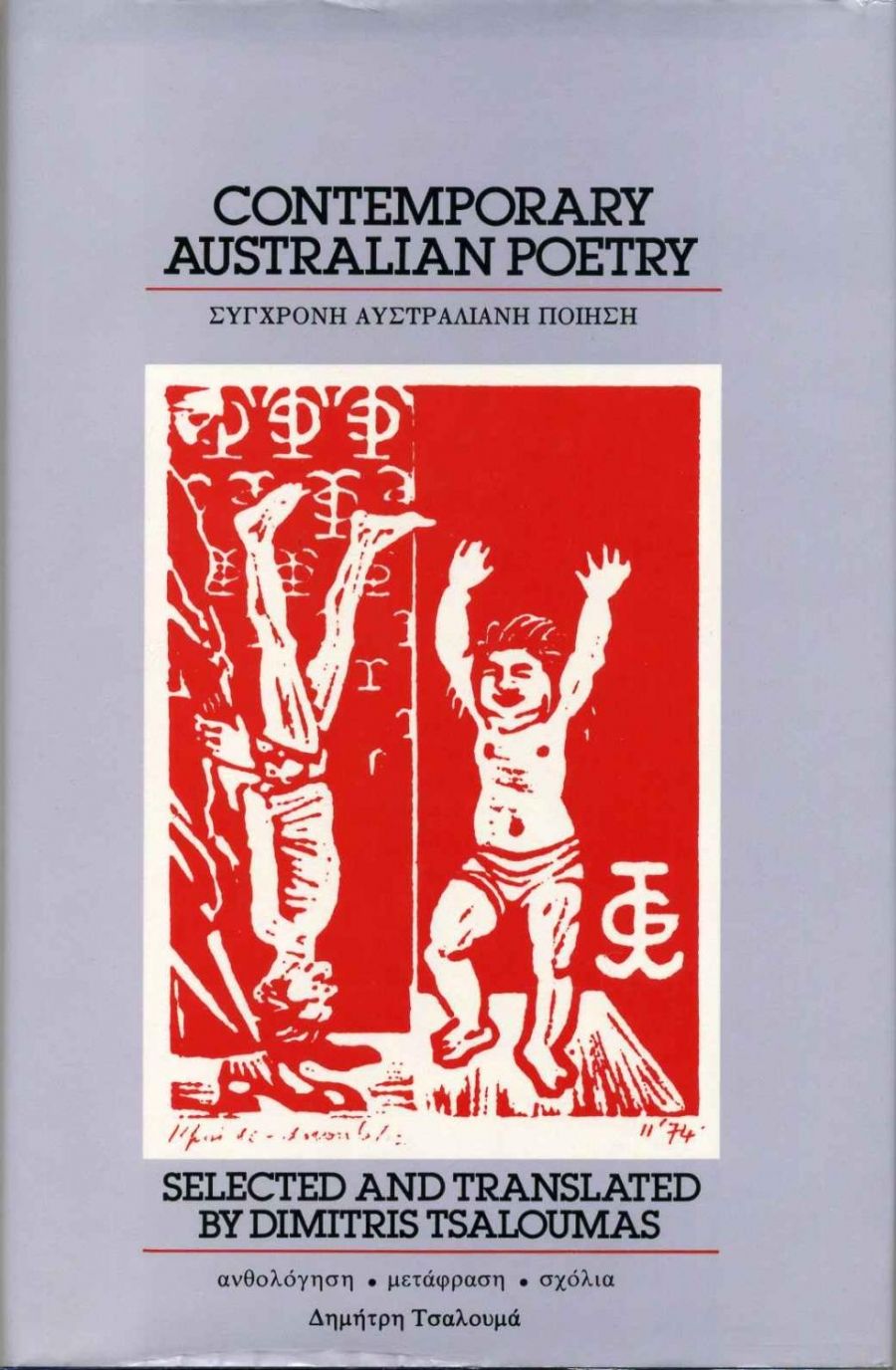

Generally, Dimitris Tsaloumas’s publications in Australia have been discussed in terms of translation, translation from Greek into English which made most reviewers long for an understanding of the original. Tsaloumas’s ‘otherness’, the difference in his poetry, has been connected with, on the one level, its bilingual presentation, its obvious physical difference. This difference is obvious again in this latest publication, the Queensland University Press’s anthology of Contemporary Australian Poetry. On first glance it too tells you that it is different; it has an excess, the Greek, for the Australian reader – not however, for the Greek. Ironically, for her this functions the other way around; the English is excess, it is strange marks on a page. Published in Greece by Nea Poreia Press in 1985, its aim was, in the words of its compiler, ‘to give some idea of the variety and wealth of the poetic production of this distant but very young and vigorous world of the antipodes’. The means through which it achieves this end are the familiar ones of translation.

- Book 1 Title: The Flower and the Word

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, 265 pp, $29.95 hb

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

This time, however, he is the translator and not the subject of translation. It was this task of the translator, according to the anthologist, that guided the choice of poems presented in this book. It was, and is, translation which guides the Greek reader in the reception of this book and shows her/him how to paint the Australian landscape.

Read in Greek, the poems have a similarity of tone and language that one finds surprising. It is the voice of Dimitris Tsaloumas that is continuously heard here; his sometimes colloquial, sometimes archaic and at times highly idiomatic language dominates the scene and, in the words of his ‘Exercise for Three Voices’, ‘opposing voices [are] stilled’. What is allowed to be heard of others here is only the brief biographical statements provided by the compiler and acting as sign posts which, rather than guiding you, leave you more perplexed as to who is saying what in these poems. Thus Tsaloumas’s task becomes not the telling of lives, but rather to use an image of Richard Tipping’s – the spelling out of the word ‘poet’:

… I was in the ANZ bank on Darling St opening an account for the Fellowship & the teller asked me: ‘occupation’, and I said ‘ah ... ah ... poet’ & he said, ‘how do you spell poet?’

Tsaloumas tells us: Slessor, Hope, Hart-Smith, Giles, McAuley, Elder, Blight, Campbell, Wright, Zwicky, Rodriguez, Buckley, Wallace-Crabbe, Hart, Mead and so on. All well-known names, all names that the Australian reader would associate with different moments in Australian poetry, but not the Greek. For her/him the illusion is created that they sound very much like Greek.

What about the other reader, however, the one who can read the other page only, the Australian reader? What does the anthology represent for her/him? Certainly, practically speaking, a different anthology of contemporary Australian poetry, one that has Greek or the Greek in it. Dimitris Tsaloumas is well known as a Greek poet living in Australia. He too gets mentioned in anthologies and histories of Australian literature as a writer of non-English speaking background. He is not representing this, however, in this anthology. He is representing ‘Australian’ poetry here, to Greeks and Australians, Australians who know the names of Slessor, Hope, Rodriguez, Wright, Taylor, Webb etc., as constituting different voices; thus the element of translation is out of it for her or him.

What makes this anthology different, then? It includes names that have traditionally been included in anthologies. One difference some might find is in the title: Contemporary Australian Poetry. The word ‘contemporary’ might figure in its cover, and the explanation might be given that the anthology is made up of poems ‘from writers whose work, or the most important part of their work, appeared after World War II and in particular from the 1960’s onwards’, but there is a timelessness in the themes to be found running through all the poems. The fact that no dates are given of each poem’s publication supplements the Greek reader’s feeling that this is one poet’s anthology, one poet’s flowering words (as anthology. is made up of anthos and logos, flower and word). The only time sequence that figures here is the consecutive order of each poet’s date of birth. The impression again is sustained that they are different voices, different times, different labels adopted by the poet at different times in his life. The names might be familiar as those of different poets appearing in different anthologies, thus giving the impression that this anthology is not presenting anything new; but here is where its difference lies in relation to the others. Tsaloumas chooses less anthologised poems of much anthologised poets. Thus the entry for Hope presents ‘The End of a Journey’; HartSmith is represented through ‘Aaron’s Rod’; McAuley through ‘Jesus’; Taylor through ‘The Cellar’; Tipping through ‘Against or for Beauty’; Blight through ‘Morgan’; Campbell through ‘Rock Pools’; Buckley through ‘Parents’; Wallace-Crabbe through ‘Introspection’ and the list goes on. Women are represented in poems by Barbara Giles, Judith Wright, Anne Elder, Rosemary Dobson, Gwen Harwood, Jennifer Strauss, Fay Zwicky, Margard Scott, Antigone Kefala, Judith Rodriguez and Jennifer Maiden, a small percentage in a book of fifty-seven poets. Poets who all together spell out the word ‘p.o.e.t.’. The poet Dimitris Tsaloumas and The Poet in general.

In general, this poet and his anthology do not aspire or claim to be definitive. The aim was not to present Australian poetry from its beginnings, but to begin presenting Australian poetry to the place of some of its people’s beginnings. As such it succeeds and fails at the same time. It succeeds in presenting names in a list to make up ‘Australia’, names that can be used as landmarks and as points of reference aiding in the entry into the symbolic (and symbols) of this foreign body, a body that most Greeks and GreekAustralians have no access to. It fails, however, to provide the differences in and variety of ‘Australians’ that make up this landscape . The surveying material that is used is well used and tried, the results are uniform. The task of the translator once again is proved treacherous.

This betrayal of the originals, however ‘is what makes this translation, this anthology, original. It is the site where the originals are rendered silent or, at best, only echoes in another’s voice, a voice which was series as other but which now has come into its own.

Not a bad beginning at reconstructing the face of ‘Australian’ poetry.

Comments powered by CComment