Mark McKenna’s analysis of Manning Clark’s Kristallnacht episode (The Monthly, March 2007) – in which he shows that Clark was not in Bonn on Kristallnacht, that he arrived a couple of weeks later, but that in ensuing years he appropriated his fiancée Dymphna’s experience and account and made it his own without any attribution – may be further illuminated, given another dimension, if we look more closely not at Clark, who, as McKenna shows, wasn’t there, but at Dymphna, who was.

Manning Clark and the beautiful and brilliant Hilma Dymphna Lodewyckx (it rhymes with ‘motor bikes’, as she would amiably tutor anyone struggling with the plethora of consonants) would have seen each other at their first undergraduate lecture at Melbourne University – Latin 1. They did not meet then or in any subsequent Latin 1 class because the standard was so low – designed to help non-language students meet the language requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts – that neither felt the need to return. But they came across each other later, and their friendship flowered as they discovered mutual interests and passions.

Dymphna, born on 18 December 1916, was the daughter of Associate Professor Augustin Lodewyckx, who taught Germanic languages at Melbourne University, and Anna Sophia (née Hansen). She had one brother, six years older, and she became something of an only child when her brother began to lead a more independent existence (Dymphna once remarked that he suddenly became interested in her when she began to attract a coterie of girlfriends). She was the darling of her proud parents, and her extraordinary intellectual promise, her physical beauty and her attractive, powerful personality led them to expect great things of her. These she duly delivered, matriculating at fifteen from Presbyterian Ladies College and spending some time at school in Germany before entering Melbourne University to study languages.

Augustin Lodewyckx, a Belgian, was an unreconstructed Europhile who could find little of value in Australia, let alone in Melbourne, where the prevailing sports mania especially annoyed him. Andrew Clark, in a memoir of his mother, describes the European atmosphere and appearance of the Lodewyckx household in the leafy Melbourne suburb of Mont Albert:

situated on an acre of land … [it] was a European oasis. The orchard, vegetable and flower gardens were demarcated by carefully stacked Flemish-style woodpiles. Outside the back door was a row of clogs. It was also a haven for the study of languages. Dymphna Clark spoke Dutch at home, and was flawless in German …

Lodewyckx’s rejection of all things Australian, which included Australia’s Anglophilia and unqualified support for British imperial policy, was neither merely quirkish nor nostalgic; on the contrary, his diatribes on these subjects were often extremely energetic, if despairing.

In 1933 Lodewyckx’s European gaze took him in a slightly odd direction and into print. In an article entitled ‘Hitler’s Early Career – The Lessons of History’, which appeared in the Melbourne Argus of February 4, Lodewyckx gives an account of Hitler’s rise to power and of some of the convictions which underwrote and impelled that rise.

Beginning with a note on the influence of Hitler’s history teacher in Linz, Lodewyckx goes on to describe Hitler’s attitude to Marxism, which Hitler regarded as ‘a pestilence which ought to be stamped out as soon as possible’. What Hitler disliked most in Marxian socialism, Lodewyckx says, ‘was its internationalism – the teaching that the nation was just an invention of the capitalist and that morality, religion, law, education were mere instruments in the hands of capitalism for the exploitation of the toiling masses …’ Lodewyckx says that ‘Hitler’s conception of true socialism in combination with nationalism – national socialism’, arose from his perception of the critical weakness of the ‘so-called bourgeois parties’. Hitler judged these to be ‘incapable of counteracting the terrorism of social democracy. To counteract this terrorism in factory, in workshop, or in meeting hall, there was only one way – another strong organisation which would appeal to the masses and oppose terrorism.’

Lodewyckx explains that Hitler ‘believes in war as the only means of true human progress. All history is nothing but struggle and warfare to him. If pacifists succeeded in doing away with war, there could be nothing left worth striving for, he thinks.’ Influenced by Gottfried Feder (an anti-Semitic economist who would become the economic theoretician of the Nazi party), Hitler developed views on, as Lodewyckx puts it, ‘the hold of international finance on all industry’. In this connection, Hitler accuses ‘the Jews … of having deliberately and cunningly sapped the life blood of the German nation’. Hitler, as ‘a powerful popular orator’, could influence his followers, and Lodewyckx details his rise to the leadership of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party in 1919, his failed ‘March on Berlin’ in unsuccessful emulation of Mussolini’s ‘March on Rome’, his subsequent determination to use political means and institutions to ‘enlist the young manhood and young womanhood of the country’, the emergence of the name ‘Nazi’ and the party’s development into a powerful force in the Reichstag.

Lodewyckx’s article was, of course, very topical. Events in Germany were preoccupying the press and the government. In the Argus in the same week as the appearance of Lodewyckx’s piece, reports note that Hitler had banned socialist and communist papers, that the Nazis had disrupted the speeches of Socialists in the Reichstag, and that they had branded Herr Loebe, the Socialist Leader, a ‘Jewish pig, scoundrel, swine’, then shouted him down until the sitting had to be suspended. Herr Loebe had triggered this attack by referring to Hitler as ‘a Slovak with bloody fingers’.

Lodewyckx returns to his discussion in the Argus of 11 March 1933, under the heading ‘Hitler’s Political Ideals – The Doom of Parliament’, and begins with a statement addressing his title. ‘The political ideals of Hitler,’ he says, ‘may all be traced back to one great principle – the essential difference of all human beings. Not only is one race superior to other races, he holds, but every individual is different from every other individual. Some are born leaders, others are born to obey. It is absurd, therefore, to give all citizens of a state equal rights. Hence democracy and parliamentary government are bound to fail.’

Lodewyckx goes on to cite what he sees as ‘one of the most amusing chapters’ of Mein Kampf, which details the life of a ‘typical “Representative of the People” who racks his brain before every general election to find some new slogan with which to hide the emptiness of his futile verbosity, and to hoodwink the stupid masses, and whose only serious concern is the keeping of his seat and his parliamentary indemnity’.

Lodewyckx points out that, for Hitler, ‘the most peculiar feature of the whole system … is majority rule. All questions are resolved by a majority vote, which is the vote of a number of people who mostly do not understand the question they are voting upon. The worst of it all is that none of them feels personally responsible or can be held responsible for his vote …’

‘Hitler,’ Lodewyckx says cryptically, ‘soon changed all this.’

This opening to the second article represents an important change of tone and style in comparison with the first. In the latter, the account of Hitler’s early ideas and the events associated with his rise to power is given without real comment – though some is perhaps implied – and, as it were, at a distance. It would be difficult not to feel that Lodewyckx has a certain admiration for the rampaging career and the impatient iconoclast he is describing. Although Lodewyckx rarely quotes Hitler verbatim, there is a real problem about identifying just whose voice is being heard at times. Still, the successive paragraphs of objective facts and chronology of events, and, towards the end, citation of numbers of supporters, and so on, help maintain a sense of restraint which, even if more apparent than real, is strong enough and palpable enough for the author to point to if anyone decided to attack the tone of his narrative.

The opening manoeuvres of the second article, however, are very different. Although Lodewyckx again uses the device of occasionally interpolating a cautionary ‘he [i.e. Hitler] holds’ or ‘Hitler thinks’, he is more caught up in what he obviously finds a persuasive, even exciting case. The vocabulary is approving, endorsing, and the tone at least energetic but verging on the exultant: ‘bound to fail’, ‘futile verbosity’, ‘stupid masses’. Even if some of these characteristics have strayed into Lodewyckx’s prose from Mein Kampf, they are still being given a good run with no suggestion of their being thought excessive or menacing.

Successive sections of this essay are deployed with the same scarcely suppressed gusto. ‘The principle which once made the Prussian army the most wonderful instrument in the hands of the German nation,’ Lodewyckx notes, ‘will be the foundation of the whole political organization – the absolute authority of every leader over his subordinates combined with responsibility to the chief above’, an organising principle which, incidentally – though Lodewckyx could not possibly have known this – would become the basis of the Eichmann defence.

Under the Hitlerian reorganisation, Lodewyckx assures his readers, ‘[c]orporations such as those we now call Parliaments will continue to exist but their members will have the right only to advise’; and ‘if doubts are raised of the practical possibility of carrying out such a plan, Hitler reminds us that the Parliamentary principle of democratic majority rule has not dominated mankind from the beginning. On the contrary, it has prevailed only during short periods of decay in States or Nations.’ That sentence, ‘Hitler reminds us’, is an important departure from the at least superficial distancing of the first article. Now it’s Hitler and us, not him and them.

Concluding his anatomy of the reorganised state, Lodewyckx sums up: ‘In other words, Hitler and his party will take control of the Government and administration in all its branches in the same way as Mussolini and the Fascist party took control in Italy …’

On other important ‘political issues of a more practical nature’, Lodewyckx explains that ‘Hitler intends to stamp out, root and branch, Marxist socialism, replacing its international ideal by his own National Socialist ideal, which must fill the masses with all the vehemence of extremism. He also undertakes to free Germany from another sinister power – that of international Jewish finance.’ Again, the general enthusiasm of the narrating voice is scarcely hidden, and the endorsement of the concept of the ‘sinister power’ of Jewry is unmitigated by tone or word. Rather chillingly, Lodewyckx’s comment on the problem of removing Jewish financial influence is: ‘How this is to be achieved, however, is not made plain’, though he presumably had little idea of how Hitler would achieve it.

Lodewyckx then turns to what Hitler sees as the urgent questions for Germany to confront and answer: ‘Bread to eat and then freedom’, Lodewyckx says, are Hitler’s first priorities. And by freedom, Lodewyckx says, ‘Hitler means above all freedom from the shackles of the Treaty of Versailles, the right to arm and to organise her own defence and security as she thinks fit’. After detailing Hitler’s ideas on future alliances, against, in particular, the continental hegemony of France which Hitler regards as, in Lodewyckx’s words, ‘a permanent menace to Germany [and one which] must be broken at all costs’, Lodewyckx ends by quoting Hitler’s statement of Germany’s political testament:

No other great power than Germany is to be tolerated on the Continent. Every attempt to form a second military power along the German borders, even in the shape of a state that might one day be organised as a military power, must be looked upon as an attack on Germany. You have the right, nay the duty, to prevent the coming into being of such a state by all means including force of arms. And when such a state exists it must be crushed. The foundation of the strength of our people must be sought not in the colonies but in the soil of the European homeland. Do not consider the Reich secure as long as she is not able to endow every one of her sons, for centuries to come, with his own plot of land. Never forget that the most sacred right on this earth is the right to own the land which one wishes to cultivate oneself, and the most sacred sacrifice [is] the blood shed for its soil.

Lodewyckx remarks, by way of conclusion, with considerable prescience but no comment either way and no hint that the scenario he sketches must contain the seeds of a huge catastrophe: ‘This testament assumes an enormous expansion of Germany, by force of arms if necessary, toward the East, at the expense of Poland, Russia and other nations.’

It might be thought that the Lodewyckx name had stamped itself sufficiently on discussions about and conflicting views of ‘the new Chancellor of Germany’, but on 13 May 1933 ‘Life in Munich – A Visitor’s Impression’, by Mrs A. Lodewyckx, appeared in the Argus. ‘With the new Italy as a background,’ Mrs Lodewyckx says, there was a natural curiosity ‘to ascertain what had happened in Bavaria on and since March 13.’ It is not clear what exactly Mrs Lodewyckx is referring to here. The Reichstag had been burned on the night of 27 February 1933, after which Hitler suspended basic freedoms and orchestrated a campaign of fear and violence. In that atmosphere, elections held on March 5 gave the Nazis 43.9 per cent of the vote.

The two significant developments on the date she mentions, March 13, were, first, that Hitler appointed Joseph Goebbels Reich Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. Culture and communications came under the control of the Nazi Party: Goebbels constantly reiterated themes of ‘blood, race and glory’ with a violently anti-Semitic emphasis. Second, Cardinal Faulhaber addressed a conference of Bavarian Bishops, announcing that Pope Pius XI had praised the chancellor’s opposition to communism.

Of the general atmosphere Mrs Lodewyckx remarks: ‘People speak glibly of a revolution and a total change of government with a smile on their lips and a satisfied twinkle in their eyes, as if they themselves had not yet fathomed the full meaning of the word “revolution”. And, indeed, they may, for fewer signs of disturbance, anxiety or ill-will could not in the circumstances be met with anywhere.’ On the contrary, the Munich that greets her is a festive city ‘gaily beflagged … for on that day the old colours – black, white, red – together with the swastika banner, were for the first time authorized and recognised by the new government’. The cheering of people returning by train from Italy and the ski slopes of Brenner and Innsbruck, ‘knew no bounds’, she says, when they caught sight of ‘the new flag’. ‘Munich,’ she says, ‘still looks well-balanced and distinguished … the streets are a sheer pleasure to the pedestrian … flanked by buildings in which the general note of harmony is restful to eye and mind’ – a welcome contrast, she adds, ‘to the frenzied rush and crowding of Swanston or Flinders Street’.

Conscious perhaps that her portrait of Munich is somewhat idyllic, she addresses the problem posed by recent events and turbulence: ‘In the midst of such surroundings, is it possible,’ she asks, ‘to imagine such happenings as have been reported by the press during the last two weeks? … One hears tell, with dramatic finish, of atrocities said to have been perpetrated within the very walls of this exquisite city. One is duly thrilled and impressed but somewhat skeptical. The listener who, not satisfied with mere rumour, delves for the truth, perhaps finds at the end of his efforts a practical joke of a somewhat clumsy nature, played in a moment of ecstatic excitement by a band of young Hitlerites.’ Not everyone, she concedes, ‘is in sympathy with the new order of things, but all are agreed that it is worthwhile and perhaps even advisable to give Adolf Hitler a chance to prove his worth’. Previous governments, older and presumably wiser, have failed Germany, so, she suggests, ‘why not see what this younger man [Adolf Hitler], with his many excellent intentions, can accomplish’. She goes on to give an example of these ‘excellent intentions’:

Today, for example, a declaration was made throughout the realm that no German should purchase whatever it might be from a Jewish house; that Jewish children were to be excluded from State schools. Although many citizens of Munich found it hard, owing to their respect for the Jews in their midst, to obey such an order, they nevertheless acknowledged the necessity thereof and gave in with a bad grace. So far nothing untoward has happened. The shops closed their doors. Some of them had ‘Jew’ or ‘German’ written on their doors and that was that. The boycott lasts for today but should anti-German propaganda continue, it will be repeated.

The ‘boycott’, of course, continued, spread and intensified, culminating a few years later in, among other outrages, Kristallnacht.

Rightly suspecting that she is wavering on to dangerous ground, Mrs Lodewyckx at this point resolves to leave ‘political matters alone, lest I burn my fingers’, and turns to the cultural joys of being in Munich. The essay ends with descriptions of lectures, tours, visits to art galleries, experimental farms, laboratories, libraries, during which they are constantly in the hands of and under instruction from ‘experts’.

Dymphna turned seventeen in the year these articles were written. In a household with such German orientations – language, literature, culture – and such European proclivities and preferences, it is reasonable to speculate that the content of the articles and the ideas sustaining them would have been exhaustively discussed around the dinner table and that Dymphna, who had already been to school in Germany, would have been very much a participant. We don’t of course know what she thought of them, though given the fine intelligence, range of reference and liberal intellectual attitudes of the grown woman, it may be that she had some youthful reservations. It is likewise unimaginable that she would not later have confided in Clark, as lovers do: some reference to the articles, among much else, would have been part of her preparation of Clark for the first meeting with her parents, especially the formidable Lodewyckx. At that meeting, Stephen Holt remarks (in A Short History of Manning Clark [1999]), ‘Clark found that he had nothing to say’; he was overwhelmed by Lodewyckx’s knowledgeable if heavily slanted tirade against most things Australian.

Whatever the nature of their confidences – the inclusions and omissions – it is clear that when Dymphna walked among the glass and wreckage of Kristallnacht she brought to that experience a background (or baggage, as they say) more complex than Clark brought to his eventual appropriation of it. ‘[I]t is possible,’ Mark McKenna speculates, ‘that one morning at Tasmania Circle, Dymphna climbed the ladder to Clark’s study, confronted him and said, “Manning, you weren’t there, you know you weren’t there. What do you think you’re doing?” Exactly why she chose to remain silent is an intriguing question. The most obvious answer is probably the right one: she was so loyal to him that she could never betray him.’ It probably is one of the right answers, although, like so much else about this gifted woman, her loyalty, though basically unswerving, was a profoundly complicated matter until they settled into the détente often engendered by old age. But it is not the only possible answer.

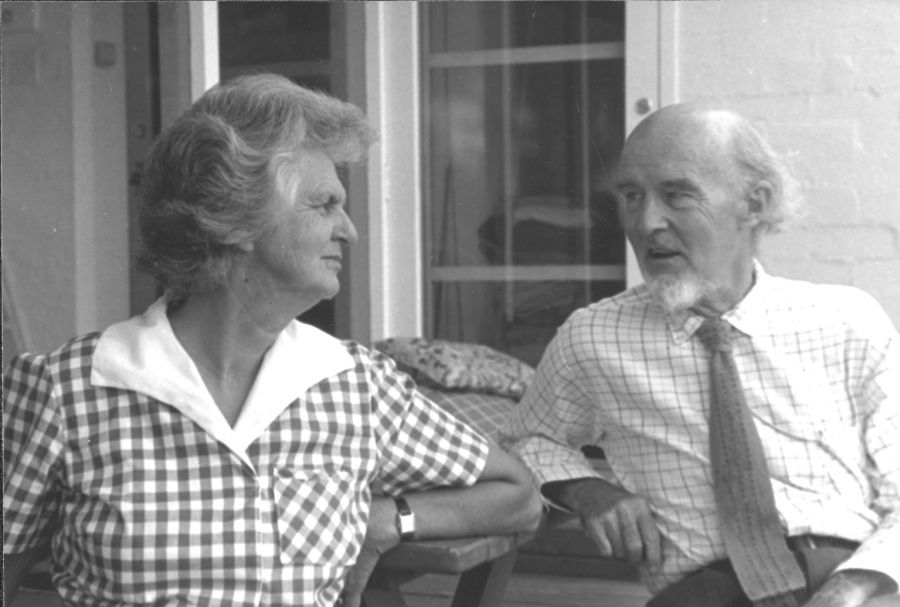

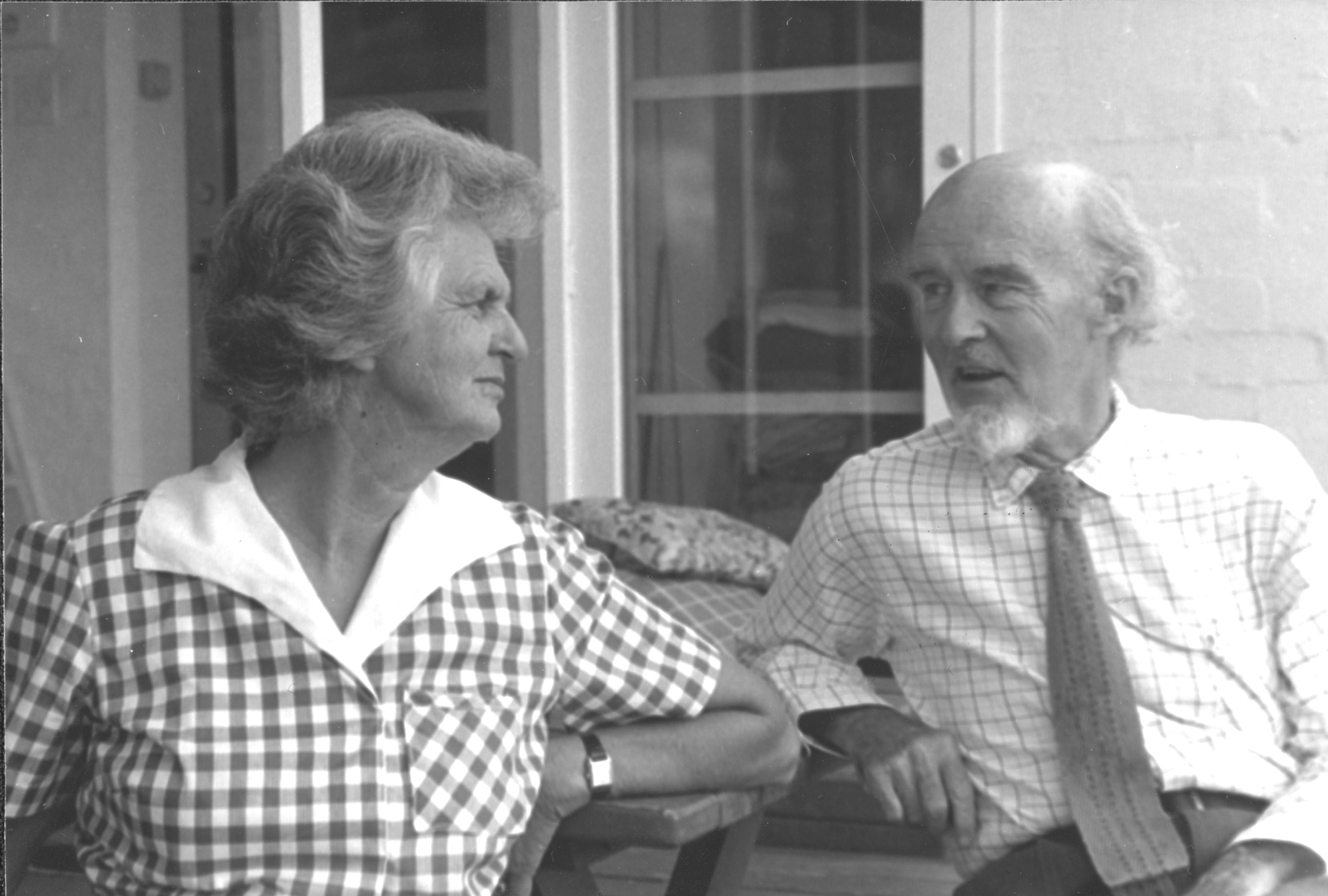

Dymphna and Manning Clark, 1984 (Alec Bolton/NLA)

Given what she knew of her parents’ stances and opinions that underwrote those articles, Kristallnacht would have posed a dialectical problem for her as far as discussing it with her parents was concerned. This is not to say that the Lodewyckxes would have approved of the events of that night, but it seems safe to say that, especially from their antipodean distance, they would have found a way of blunting the reality and significance of the occasion, since they had managed to do that with much that had gone on already in Hitler’s incumbency, much that was at least equivalent to, if not as overtly sensational as, Kristallnacht. Always close to her doting parents, Dymphna was unwilling to open a rift that would be potentially so divisive within the family. It doesn’t take much imagination to see that you could buy a fight in the Lodewyckx household on the Third Reich. So Dymphna told her story to Clark and he took it all in: neither of them was to know at the time that he would appropriate it, make it his own, and it was years before he publicly did, by which time Dymphna’s parents were dead (Augustin in 1964, Anna in 1967).

It does seem to be the case that the first public airing of the story of Clark’s Kristallnacht adventure appeared in 1978, and that the historian, Professor Rob Pascoe, revealed it in his National Times piece, ‘The History of Manning Clark’. As a colleague of Pascoe for seven years (1997–2003), I had many ‘Clark talks’ with him. That anecdote was one of our topics and one which Pascoe felt he had been the first to report.

But that Clark would appropriate the Kristallnacht story is neither such a mystery nor so heinous as some have sought to establish. There are many persistent themes and preoccupations, not to say obsessions, in Clark’s early diaries: one of them is his desire to write, to be a writer. As well as the explicit diary entry, ‘I would like to be a writer – But how? My style is poor …’ and so on, there are others which in one way or another harp on the same theme, express the same sometimes desperate wish. He expresses disgust with one of his essays because ‘the ideas are quite sound but the powers of expression are too limited and quite often it is impossible to express my meaning’ (23 January 1939). As a remedy, he resolves to read exemplary prose: ‘This wave of laziness must cease – and the stimulus must return. My writing still lacks life, and the sentences lack connection, too much like entities in themselves … I must read more good English, the works of the great masters …’

He laments his ‘carelessness in choice of words’ and his ‘enigmatic expressions’; he resolves to seek a ‘more exact and lucid language’ (24 January 1939). References to his ‘inability to express [himself] adequately’ crop up regularly in the diaries of his Oxford days. After a failed day (26 September 1939) working on de Tocqueville – ‘9 lines, very poor in quality’ – he adds: ‘More determined than ever to be a writer, but still doubt my powers – I have wasted my life. What is my motive? I think men who write are types who cannot satisfy the craving for being noticed except by writing …’ At the end of the notebook containing the diary entries for 25 November 1938 to 5 May 1940, he farewells ‘this book – a record of failure …’ (28 April 1940). But in the new diary, begun immediately, he writes: ‘A new book of reflections – begun with the hope of doing something, of creating something. I would like to do two things, to write a [‘good’ crossed out] novel which would be a faithful reproduction of my own experience of life – with its extremes, the unutterable, unanswerable sadnesses, the delicious sensations compared with the hopelessness, the purposelessness of most people’s lives, and the guilt I have always felt but never repressed. One could compare the desire for harmony with our failure to sustain it – the uncompleted tasks. Then I want to write a biography of de Tocqueville …’ (4 May 1940). Three days later: ‘This month I must write something definite – I think it would be best to start on a small subject – say relations between England and Australia – or the reflections of an exile.’

After he and Dymphna returned to Australia, his diaries during his teaching stint at Geelong Grammar School are full of plans to write, to ‘write an article or a sketch – something individual’, or self-excoriations for being ‘too lazy’ to write, or innumerable projects like, ‘Why not write a number of sketches beginning with Louis Burke each one to end with an observation on human nature’, or reflections on ‘the gulf between the great ideas in my mind and the poverty of what I put down’, or speculations like ‘Perhaps I could create something if only I had the idea and the discipline … I must write two pages on a subject and not meander’, and so on.

In the claustrophobic atmosphere of England on the eve of war and the relative isolation of Corio after their return to Australia, Clark did not know, and would not have been much comforted if he had known, that his flounderings, his sense of burgeoning ideas that diminished as they approached the page, his conviction that great formulations and images somehow became impoverished when he expressed them, were all typical of the young would-be writer and only those who battled through that phase, continuing to fill pages with work that disgusted or depressed them with its banality, clumsiness or dissonance, would have the chance to write memorably.

It is easy for us, reading the diaries years later, to realise that the man who speaks of the unutterable sadnesses, the hopelessness of other people’s lives, the ‘small subject’ of Anglo– Australian relations and the ‘reflections of an exile’ was only in his relatively sheltered mid-twenties and had been away from Aus-tralia just one year. But he is not to be derided for this: only those who are deeply driven to write, who suffer agonies of desire to create in what seems a wilderness barren of ideas and subjects, can see themselves in this way without irony. Clark, like Henry Lawson, wanted above all to write – history certainly, but much else.

So he battled on: his days were consumed with ideas, stories, the work on de Tocqueville, sketches. Like all writers, he was on the lookout for material. His colleagues at Geelong Grammar School all came into his focus as possible characters or the bearers of interesting stories, intriguing conflicts, woes and hopes. He had long since had an ear for stories and for captivating events and people. Some of his later diary entries read as prose drafts which may come to nothing but provide at least the satisfaction of some craft, some creativity that takes off from the bare observation.

High mass at Brompton Oratory; then to Stepney and Wapping where convict hulks were once moored in heart of east end with faint uproar audible from the ‘great city’. Visible: the spires of the churches with that promise of mercy for those who confessed their faults, and divine love and forgiveness, in contrast with their own squalor, wretchedness, filth and the never-ending lapping of the waters against the walls of the Thames and the light of the ships which had come over the ocean then as they waited for their journey across the oceans of the world as well, possibly, as the oceans of life which might wash away their crimes and give them that time, that opportunity for the amendment of their lives … While sitting down, one is aware of the smell, that blend of human and animal excreta with water, that faint suggestion of fowl poop which must have been more pervading at the beginning of the nineteenth century. (9 August 1964)

Although this begins to run out of control, it is fascinating for its sense of the writer flexing his muscles, being borne up with his ideas and his observations, not knowing quite where he is being led.

The Kristallnacht story looks like it was one of the first that Clark recognised as ‘material’, what Henry Lawson called ‘copy’, not necessarily at the time, but especially in those early years of agonising for a voice, a topic, a narrative trigger; with much else it sat, as is the way with the creative imagination, waiting its hour, and, when the time came, Clark took it over and made it a part of a different story.

Whether he should have done so is another matter, which can be duly considered. Suffice to say, for the moment, that writers do this all the time. Lawson’s arguably most famous story, ‘The Drover’s Wife’, recounts an experience of his mother, Louisa. She was a renowned raconteuse, and he heard her tell it often, with variations. She showed some resentment in later years when the story became so well known and loved. Likewise, ‘The Loaded Dog’ was a bush yarn that had been around for some time before Lawson got hold of it and it was claimed by many a storyteller. In both cases, Lawson appropriated the story and, with his touch of genius, made it his own.

But the time for Clark’s Kristallnacht revelations was governed by external as well as internal forces. If Dymphna wrote of her Kristallnacht experience to her parents – and it beggars belief that she would not have done so, in some form or another; for one thing, she would have had to assure them of her safety, for another she would know of their vigorous interest – it would have been impossible for Clark to claim it as his own while the Lodewyckxes were alive. This was not only for the obvious reason that it would have become an incredibly complicated yarn to spin to the Lodewyckxes, with Clark fabricating and Dymphna knowing he was, but also because Clark would have had a hostile audience. He did not get on with the Lodewyckxes. Like any loving and proud parents, Augustin and Anna were disappointed in Dymphna’s marrying someone whom they regarded as not at all ideal, and they were especially disenchanted that it had happened precipitately, as far as they could see, and overseas. They feared the marriage would mark the end of Dymphna’s brilliant scholarly career and prospects, which by and large it did, though Hitler didn’t help. Whatever other, probably inner, reasons explain why Clark did not make his takeover move on the Kristallnacht story until nearly forty years after he missed it by a couple of weeks, the complications inherent in his relationship with the Lodewyckxes were important constraints.

He would not have approved of the general tone of the Argus articles, whether they were recounted in summary to him by Dymphna or whether he eventually read them. And he recognised that the circumstances of their marriage were tendentious for Dymphna as well as her parents. A week before their wedding, he wrote:

[Dymphna’s] letter today was disappointing. It made me feel quite sad, almost bitter and angry. She is not really deeply attached: her youth is not over, and her affections are by no means canalized as yet. She is still restless, still anxious to snap at diversions which are meaningless. Her cosmopolitan tradition, her lack of certainty as to her loyalties may be the cause of this. I don’t think she has any deep attachment to Australia and I fear that these bursts of frivolity, acts of irresponsibility will remain with her for a while. I wonder whether she will ever settle down or will always long for the roaming, restless life, always chafing against domesticity and permanency. The handling of this problem will require infinite tact & patience from me. She must have diversity, change of scene, novelty of action. Heaven help me if my imagination should fail me, or if my ways of life should become more sedentary & less active! I do hope that her spirit will not interfere too much with my work.

And on the morning after the wedding of 31 January 1939, he wrote:

In the morning [Dymphna] seemed to be despondent again, and her fears for the future were always lurking in the back of her mind. She needs purpose, reassurance. Her plaintive protests against her present position, her fear of living the life of a parasite, which is sometimes tantamount to an obsession, will fade with her realization of her new future. Perhaps she is unwilling to make the final surrender, and is still hankering after her independence, her old isolation … In the afternoon I wrote a long letter to Mrs Lodewyckx setting out the reasons for our marriage.

Aside from the self-absorption of some of these observations, it is clear that Clark sees connections between what he regards as faults or problems in Dymphna and her parents’ attitudes and the nature of her upbringing. His relationship with his parents-in-law was always difficult, often acrimonious. On 16 February 1939 he notes: ‘This morning I received a very disturbing letter from Hope [Clark’s sister]. She told me of the marked disapproval with which my plans had been received in Melbourne. The mistrust & suspicion of those who had hitherto placed unqualified confidence in my integrity upset me …’ He complains that his actions, which included his marriage, and plans have been distorted ‘into the irresponsible acts of a profligate, intent on wrecking not only his own career but also that of his talented fiancée [sic], the innocent dupe of his immoral ambitions … The attitude of Mrs Lodewyckx is a keen disappointment to me. From her I did expect some understanding of my position, and the sympathy which she is capable of. But her reaction is, I fear, dominated by her pride in her daughter – the satisfaction of which she expects despite the dangers which she might have to endure. I think this is why she is so anxious for me to make no change in my plans …’

At another time he observes, ‘Mrs Lodewyckx still lacks faith in me: they all display a fiendish delight in trying to bring me [‘low’ crossed out] down off the pinnacle on which my mother sets me: to expose my faults, laugh at me (a laughter which is often a jeer), call me incompetent, selfish – anything. But they will never shake my mother’s faith. One day I shall reply – fully, but the time is not ripe.’

Perhaps the most depressing moment in Clark’s succession of agonised self-scrutinies about Anna Lodewyckx came with the news of her death: ‘At midnight on Monday 2 October [1967],’ he wrote in his diary at that time:

[M]y mother-in-law, Mrs Lodewyckx, died. I don’t believe anyone has hurt me as much as she did. She said earlier that my mother had spoiled me, that I was a sensual animal, that I only courted publicity … Yet, all those attacks were a long time ago. We started hating each other years ago and moved into a relationship as between the dead, where neither said a significant or meaningful word. So at the death I felt nothing, and did not weep, though in all other fields of life my tears flow all too freely. I wonder why we hurt each other as we did. I wonder why we were such swines to each other.

All things considered, then, it seems to me reasonable to propose that Kristallnacht, for Dymphna, for Clark, became the focal point of an intense and intricate complexity of personal forces, conflicts and anxieties so threaded through their own relationship, so ramified by Dymphna’s relationship with her parents, as to transcend even the strange phenomenon of Clark’s having appropriated it forty years on. No doubt, he shouldn’t have made it so exclusively his own, though, as I have said, writers do that. And in any case, after its various fugitive airings, Clark’s Kristallnacht story found its place finally not in a history but in autobiography – ‘a lying art’, as Clive James has observed.

Two interesting phenomena in particular are often remarked upon by writers as distinct from theorists of autobiography. One is the extraordinary amount of material, the torrent of recall, that seems somehow to be unleashed once you seriously commit yourself to cruising your past. And the other is the certainty, the utter assurance with which you regard some items in that torrent: you know you remember them, that’s how they were, beyond question. At one point in an autobiography that I published some years ago, A Fine and Private Place (2000), I described in great detail the colour, script and names that appeared on the side of the baker’s cart that used to deliver to our house in Havelock Street, St Kilda. One day, in idle conversation, but fortunately before I had submitted the manuscript, I detailed this memory to one of my innumerable aunts. I wasn’t checking; I knew I had it right and I was telling her for her interest and pleasure. But as soon as I was well embarked on the story, she interrupted me with what she said were the correct details, and the moment she did I knew I had been wrong. I’d conflated two occasions in my boyhood and nothing was clearer once she painted the real picture. The rock-solid nature of my previous assurance, however, was rather worrying.

Sometimes autobiography cheats the narrating and recalling consciousness in a different way. Recounting in the same book a harrowing, emergency trip to hospital in which I was attempting to keep up with the doctor who was driving my wife and seriously ill baby daughter at breakneck speed to the Children’s Hospital, I wondered about including in the narrative the appearance of a motorcycle policeman who, initially intent on booking the doctor, became his siren-blaring escort once the situation was quickly explained to him. The moment I had decided on this ‘fraudulent’ dramatic insertion into the reality (‘the lying art’), I realised it had actually happened and that, for various reasons – one of them possibly being that the baby died hours later – I had blotted it from my reconstruction of those events. Autobiography is not a lying art, necessarily, but by having the autobiographer always at its centre it creates a pressure on the narrator which is sometimes too much to bear and too subtle to be truly aware of, and the truth of fiction becomes as exciting as the cold and holy precision of accurate recall.

Dymphna might conceivably have protested in later years, as Louisa Lawson – the original drover’s wife – protested to Henry, but, for all the reasons deployed here, the matter slumbered for decades, by which time, as happens to everyone who tries to piece together his or her distant past, and especially as happens to autobiographers seeking to make a narrative, a drama, of those pieces, Clark was in Bonn on the morning after Kristallnacht. He remembered it clearly and with an unqualified passion.

For her part, quietly and without fuss, Dymphna twice adjusted the record: once in an interview with Deborah Hope for the Weekened Australian of 6–7 June 1998, which, reporting her account, reads, ‘Manning, a student at Oxford at the time, visited Dymphna in Bonn shortly after Kristallnacht’, and then in a Radio National broadcast on 7 and 11 June 1998, in which Dymphna, having recounted her own Kristallnacht experiences, says ‘Manning Clark soon visited me for the Christmas break’, clearly positioning the visit as later than the events she has just described.

Allowing for all that, it seems to me extravagant to assume that all his autobiographical accounts, and those many moments in the histories when the figure and the tones of Manning Clark ghost through the narrative, are compromised by the Kristallnacht episode, like an original sin. Perhaps on reflection – years of reflection – Clark seized upon that most archetypal, frightening and proleptic Nazi moment and made it central, as he claimed, to his psyche, because that was his answer to the Lodewyckxes and their Teutonic rage. He replied at last. The time was ripe.