- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

If the role of myth is to elaborate an unbearable truth so frequently and variously that its burden is made bearable, it is no wonder that the story of Orpheus and Eurydice exists in a multitude of retellings and a plethora of different versions on canvas, screen, stage and disc. Most of these remain faithful to its romantic-tragic paradigm: boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy does not get her back. Consumers of this myth of inexhaustible mystery willingly relive, time and time again, the magnetic pull of fathomless love and the black hole of inconsolable loss.

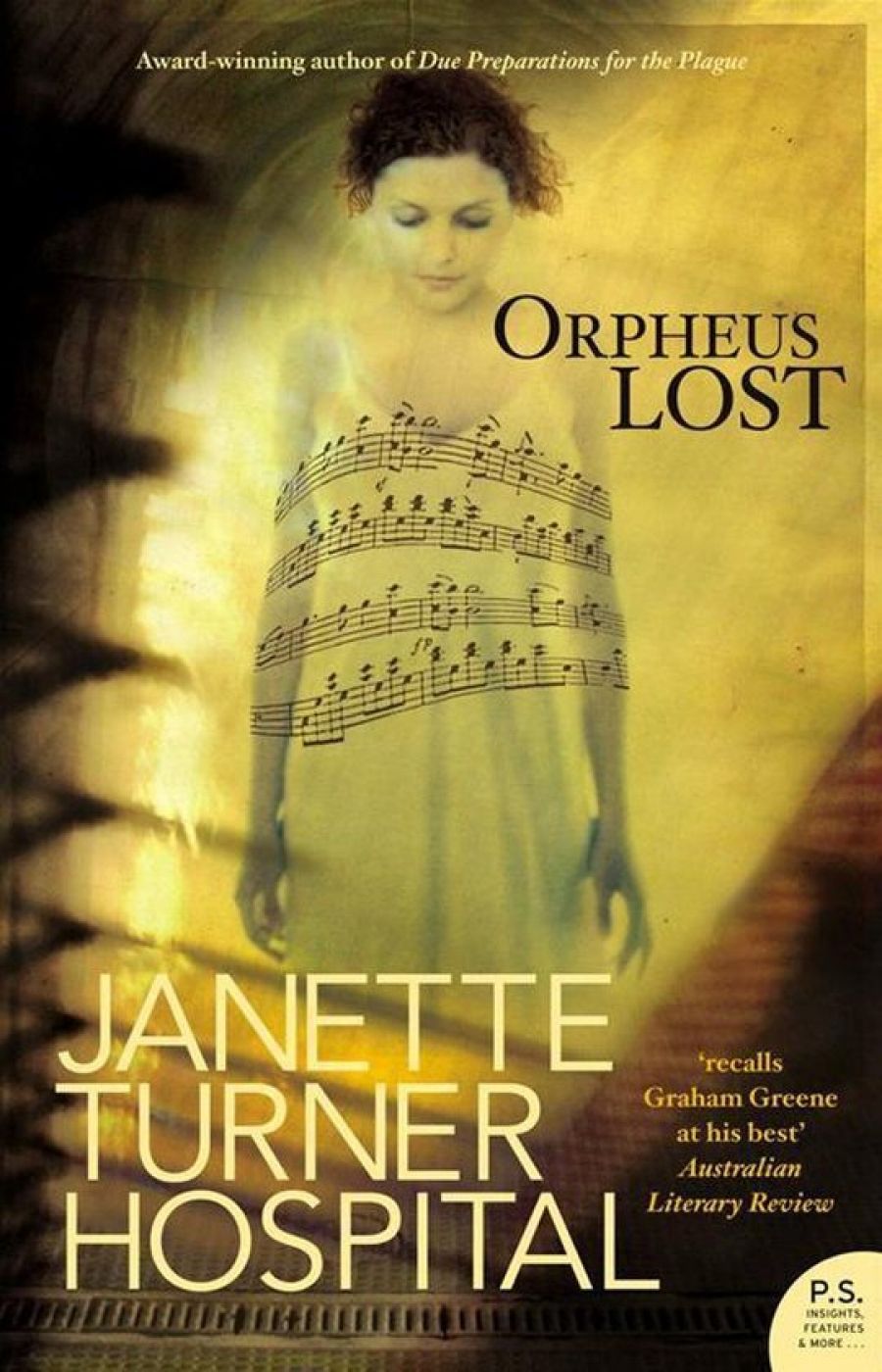

- Book 1 Title: Orpheus Lost

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $32.99 pb, 350 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/6by5bq

A brilliant example of how easily and wonderfully this model translates to other times and places is Marcel Camus’ classic Brazilian-French-Italian film Orfeo Negro, Black Orpheus, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1959, and Academy and Golden Globe awards for Best Foreign Film. Heartbreakingly sad yet exuberantly vibrant, it is a fabulously colourful version, set amidst the spectacular scenery of Rio de Janeiro during Carnaval; the action is constantly accompanied by the drumming and dancing of the samba schools, and haunted by the most beautiful song I know (‘Manhã de Carnaval’ – Morning of Carnaval). The understated context is the poverty of the favella-dwellers, who live for this yearly outpouring of festival and make-believe: the government giving them little bread, they throw themselves into self-made circuses. Yet Eurydice, a naïve girl from the country who loses herself in the crowd in the vain hope of eluding a male predator (the Aristaeus – Orpheus’s rival – of the New World), cannot escape death, the not infrequent fate of many innocents who come to volatile Rio.

Janette Turner Hospital, author of the newest literary rendering, has used musical themes and monstrous characters before, notably in her second novel, The Tiger in the Tiger Pit (1983). She has also shown amazing prescience: Borderline, her 1985 novel, dealt with illegal immigrants, one of whom is left behind in the meat-truck that is transporting them. By 9/11 she had almost finished Due Preparations for the Plague (2003), which uncovered the layers of double-dealing and multiple aliases that are the natural furniture of a novel springing from hijackings (two), Middle Eastern terrorists and echoes of international events such as the Lockerbie and Entebbe disasters.

All of these themes are not only aired but reach a new crescendo in Orpheus Lost, although the myth is given a savage gender tweak. Fearless, intense Leela-May Magnolia Moore, an unlikely Eurydice from a town called Promised Land, South Carolina, is a specialist at Harvard in the mathematics of music; she is the one who finds, seduces, loses and is forced to seek her Orpheus, a musician of complicated provenance called Mishka Bartok (no relation to the composer). Mishka was born to a mother whose Hungarian Jewish parents migrated to Australia and built an incongruous house with turrets, minarets and gables in the heart of Queensland’s Daintree rainforest; the never talked-of father disappeared before his son’s birth. Mishka is predictably a misfit at primary school but happy at home, where the music that provides the spiritual sustenance of his mother and grandparents can be heard every night, thanks to the violin of Uncle Otto. It’s just that Uncle Otto plays in a room from which he literally never emerges and is thus never seen. There is a strong touch of magic realism about this family, which Mishka inherits and carries with him on a scholarship to Harvard, where Leela is a post-doctoral student. That the highly attuned Bartoks frequently listen to silent music is perfectly credible, but that they do so collectively, accompanied by critical discussion, must also be swallowed. One does, just as Leela accepts that Mishka genuinely hears music in their silent bedroom in Boston.

Necessary to various movements in the complex plot are long flashbacks to the childhoods and formative family relationships of both Leela and Mishka. One of Leela’s playmates while they were both growing up in Promised Land was Cobb Slaughter, the boy with whom she childishly mingled blood. But to Cobb’s bitter chagrin he discovers, by spying on her, that he is far from the only one she favours sexually. He thus has a lasting grudge to work out, not so much on Leela herself – other than by giving her a lesson in fear – but on anyone who seriously takes her fancy, like Mishka, in whom he discerns a vital weakness. Though outstandingly gifted, Mishka lacks one thing that the boy from Promised Land does not: Cobb’s father may come of brutal army stock and stink of corn whisky, but he is an adequate parent. Both Mishka’s vulnerability, and the hinge of the plot, stem from his obsession with the identity of the man who fathered him and then abandoned both mother and embryo.

It is not giving anything away to say that all three characters become embroiled in a series of terrorist acts, kidnappings, cat-and-mouse tactics, games of revenge and anguished searches which take them back to origins, even to Mishka’s rainforest. Australia, where Hospital was born (she has spent more time in Canada and the United States), becomes a vivid haven of Opera House ferries and blue quandong berries, of sun-bleached landscapes and brilliantly coloured parrots – another Promised Land, perhaps one where dreams could come true.

With this, her eighth novel (several of the earlier ones having won distinguished prizes), Hospital shows her dazzling skill at thriller writing. This is not a generic put-down. The myriad twists and turns of the compellingly logical plot, the psychological scaffolding which convincingly underpins behavioural veracity, the darts from one country, one generation, one kind of wildly different mind to another – all are handled with the ease of a master-planner who never falters for an instant. Nor do the pace and intensity let up. While the events might sometimes be described as hectic, and some of the later scenes as lurid, they are no more so than the contents of today’s newspapers.

Orpheus Lost will probably be read more for the plot than for the characterisation – only Cobb shows any internal development – while some readers may be irritated by the cultural baggage and the occasional lapse into over-the-top writing: Leela dials Australia and hears underground rivers, the ‘wash and shush of the Pacific’, ‘the Daintree in full cyclonic flood’. She can even ‘feel the overspill of the Daintree on her cheeks. She could feel floodwater rising ...’ All this in a phone booth in Harvard Square! But such passages are the author’s trademark; they heighten the dizzying effects of this consummate, nail-biting example of a myth retold for modern times, when interpersonal morality is the only sort there is, but can still be undermined.

Comments powered by CComment