A book connecting Artificial Intelligence with storytelling around a Stone Age campfire certainly piqued my interest, especially given the stratospheric success of its author’s earlier works. Indeed, historian Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens (2011) was so successful that in 2019 he and his husband, Itzik Yahav, cofounded ‘Sapienship’, an initiative advocating on global challenges through focused conversations and global responsibility. In this spirit, Harari’s latest book, Nexus, focuses on the AI revolution. His Homo Deus (2015) also tackled this theme, but here Harari recapitulates ideas from both these earlier books and then develops them using an innovative framework that reviews history in terms of the impact of information networks. It is the relaying of information, says Harari, that connects Stone Age storytellers and AI.

With the development of each new information technology – from oral stories to clay tablets, from chalkboards to paper, from pamphlets to newspapers, the printing press to computers – humans have faced unexpected consequences and dilemmas. Harari aims to illustrate these dilemmas so that we, as a society, are better prepared to handle the AI revolution wisely.

Given the recent enquiry into the Robodebt scandal of 2018-19 – where flawed AI algorithms were marshalled in the hope of catching cheating welfare recipients – Australians are in no doubt about the dangers of using this technology unwisely. In Nexus, Harari gives examples such as the Iranian facial recognition surveillance system that automatically sends SMS warnings to women caught not wearing headscarves in private cars. The AI ‘sends its threatening messages within seconds’, Harari writes, ‘with no time for any human to review and authorize the procedure.’

His answer to digital overreach is to build institutions that ‘combine the powers of humans and computers to make sure that new algorithmic tools are safe and fair’. Nexus discusses many areas in need of regulation, including the now-infamous social media algorithms designed to view human users simply as ‘attention mines’. Having discussed the results of studies showing how social media has been used to undermine social cohesion in various countries, Harari writes: ‘The algorithms reduced the multifaceted range of human emotions – hate, love, outrage, joy, confusion – into a single catchall category: engagement … An hour of lies or hatred was ranked higher than ten minutes of truth or compassion …’

This is not new, but it is still startling. Then there is the Silicon Valley business model, which hacks our emotions to gain our attention and then takes our data in exchange for its services. Harari repeats a sobering story told by Kevin Kelly, founding editor of Wired, about his meeting with Google’s Larry Page at a 2002 party. Kelly asked Page why he was bothering to create a free search engine. Page replied that Google wasn’t interested in searches; rather, ‘We’re really making an AI.’ Two decades on, we are seeing just how problematic this use of our data has become: AI has not only beaten human chess and go champions; it can also synthesise information and present it so well it is hard to tell if what we are reading, hearing or seeing is ‘real’.

In cases such as Robodebt and surveillance systems, the fault is not only with the code writers but with politicians who seek to delegate human compassion and due diligence to an algorithm. Harari goes on to suggest even more frightening possible scenarios, now that AI is capable of making its own decisions. His examples of this capability include the unprecedented game strategy mysteriously created by the algorithm that defeated the world’s go champion, and GPT-4 lying its way around the ‘are you a robot?’ guardrail used by many websites. What will happen to humans, he asks, if we are left out of the loop completely?

To answer this question, the first two parts of the book offer a sweeping view of how information networks have shaped our societies. Oral stories could unite people into tribes with shared world views, but large-scale states were not possible until information could be disseminated quickly throughout a far-flung polity. The institutions that curate this information have differed between various societies, in the weighting given to information designed to find truth compared with that used to maintain social order, and consequently, in the degree to which errors – of fact or interpretation – are corrected. The key to democracy is, Harari writes, that we can hold conversations with each other, because we have institutions that limit the power of political and corporate leaders and enforce order, but which are self-correcting because citizens have access to information and the ability to vote. Science, too, is self-correcting, through experimental replication and peer review. Harari contrasts these with, for example, centralised information systems curated by totalitarian governments whose goal is keeping order at the expense of finding facts and admitting mistakes, or religious institutions that, viewing their holy book as infallible, are unwilling to modify harmful doctrinal injunctions.

Writing rigorous, popular non-fiction is challenging, though, for writers must be selective in choosing their material. Harari says he is focusing on the problems of AI because the advantages have been spruiked enough, especially by AI’s creators. Yet so have its flaws, and many of Nexus’s examples and speculations are already well known. Still, Harari’s historical perspective is fresh, and he is adept at selecting intriguing illustrative anecdotes (although sometimes he does cherry-pick to support his arguments).

Nexus’s historical framework is built on Harari’s assertion, first presented in Sapiens, that ideas such as freedom, money, and nationhood are ‘intersubjective’ – fictions that are useful for connecting us, but which are not objective facts. Here he claims that information, too, is more about connecting us than conveying facts. This offers a stimulating historical lens, albeit a necessarily simplified one. In discussing ancient Mesopotamian data collection, for instance, or the totalitarian Qin regime’s introduction of standardised coinage, weights, and measurements, Harari explores the creation of centralised bureaucracies rather than, say, mathematics. This, in turn, affects his approach to AI. For example, he often contrasts the ‘alien’ nature of AI with our biologically rooted imaginations, but he doesn’t explore the uncanny power of mathematics to take us beyond everyday imagination, nor does he use maths to make AI more understandable. But this is not his brief: a writer of popular history must choose a viewpoint. As Harari notes, human networks are more likely to cohere around an inter-subjective construct – a religious book or national constitution, say – than a factual equation.

Harari highlights the radical difference between these earlier networks and AI-driven ones, where the power lies with a handful of under-regulated corporations, and with algorithms that can make decisions in ways that no human yet understands. He doesn’t discuss technical breakthroughs in understanding AI or new proposals for guardrails; rather, he powerfully conjures the terrifying prospect of AI run amok. He leaves no room for doubt about the apocalyptic dangers.

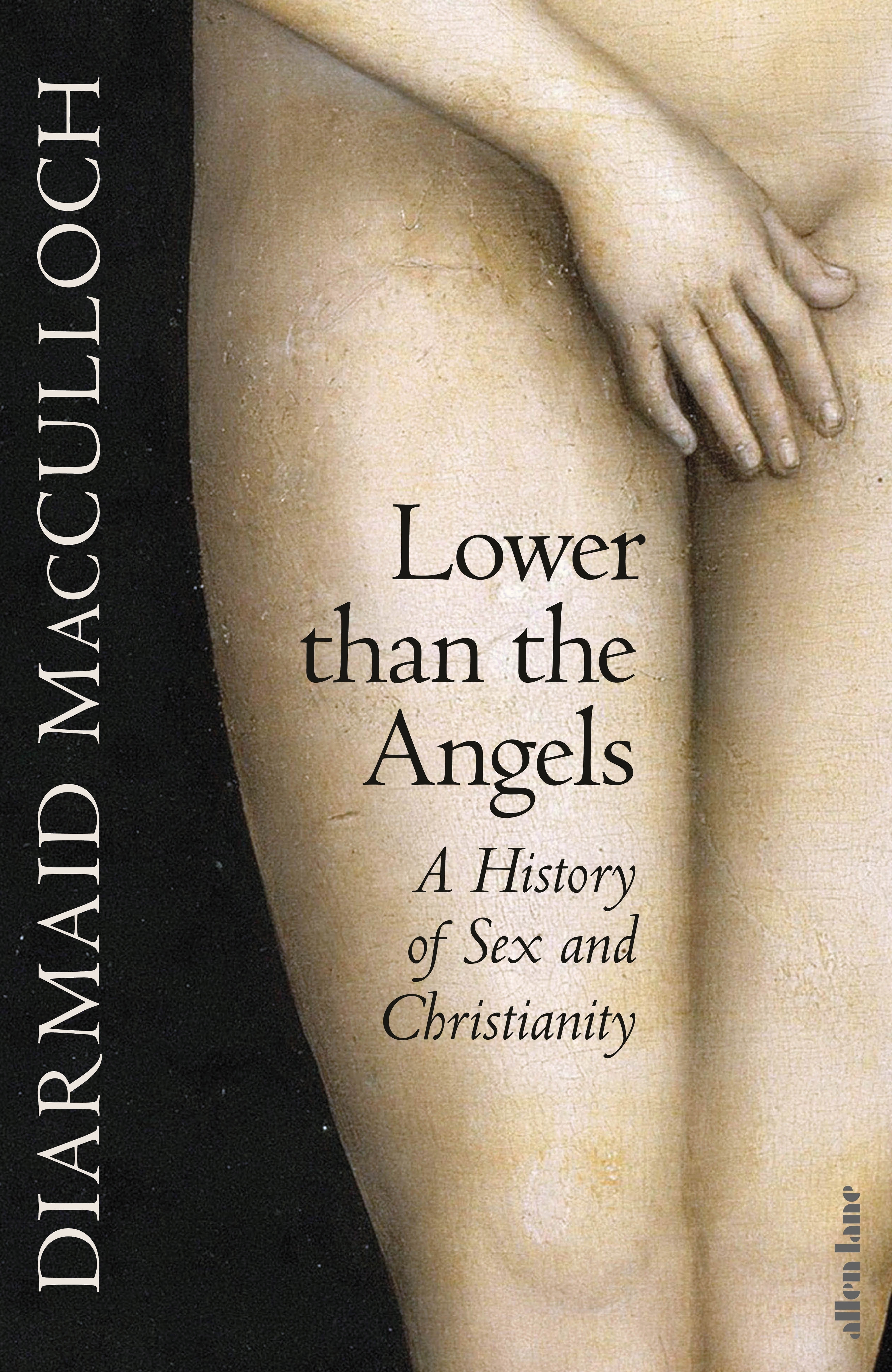

He does not link the problems of AI to neo-liberalism running amok; instead, he chooses fascinating historical comparisons, from misogynist curators of the Bible and print-fuelled witch-hunting outrage to ‘data colonialism’ and religious and digital mind-body splits – for Harari’s goal is to encourage readers to look more closely at what information networks can do besides simply conveying information. Then, he hopes, we can build a future in which AI’s alien intelligence helps rather than destroys us.

.jpg)