- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Hybrid genre

- Article Subtitle: Surveying war histories

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

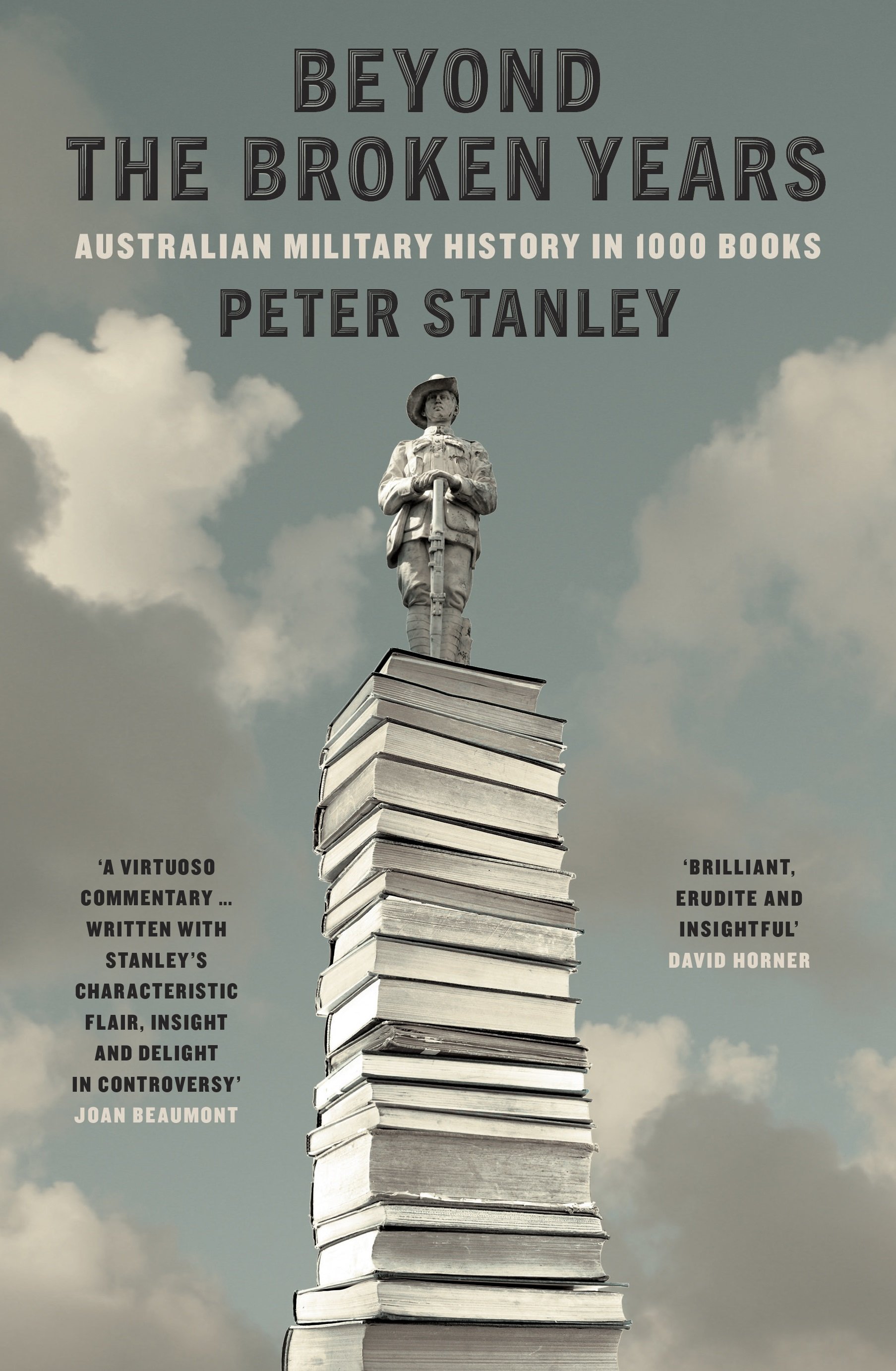

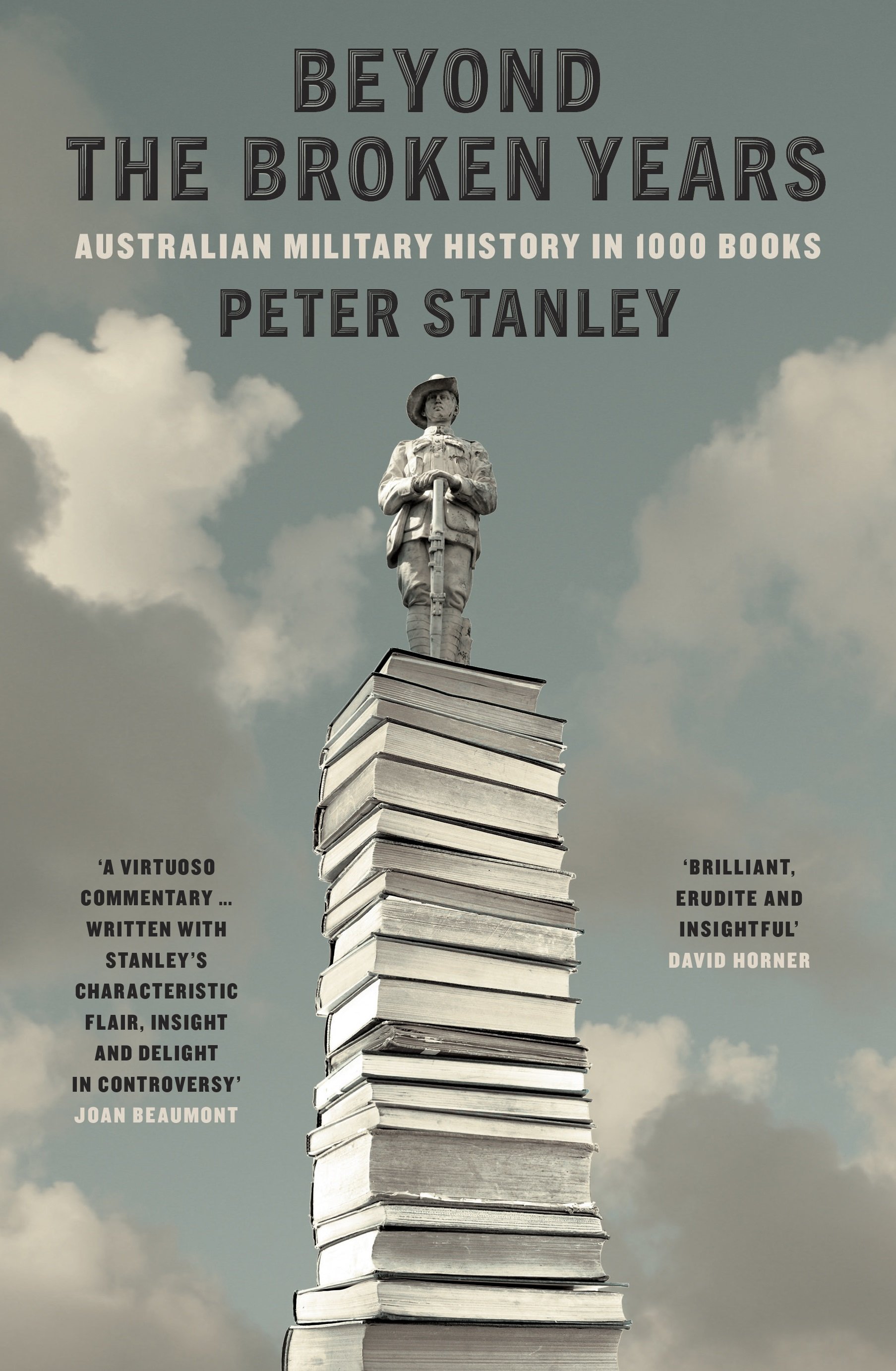

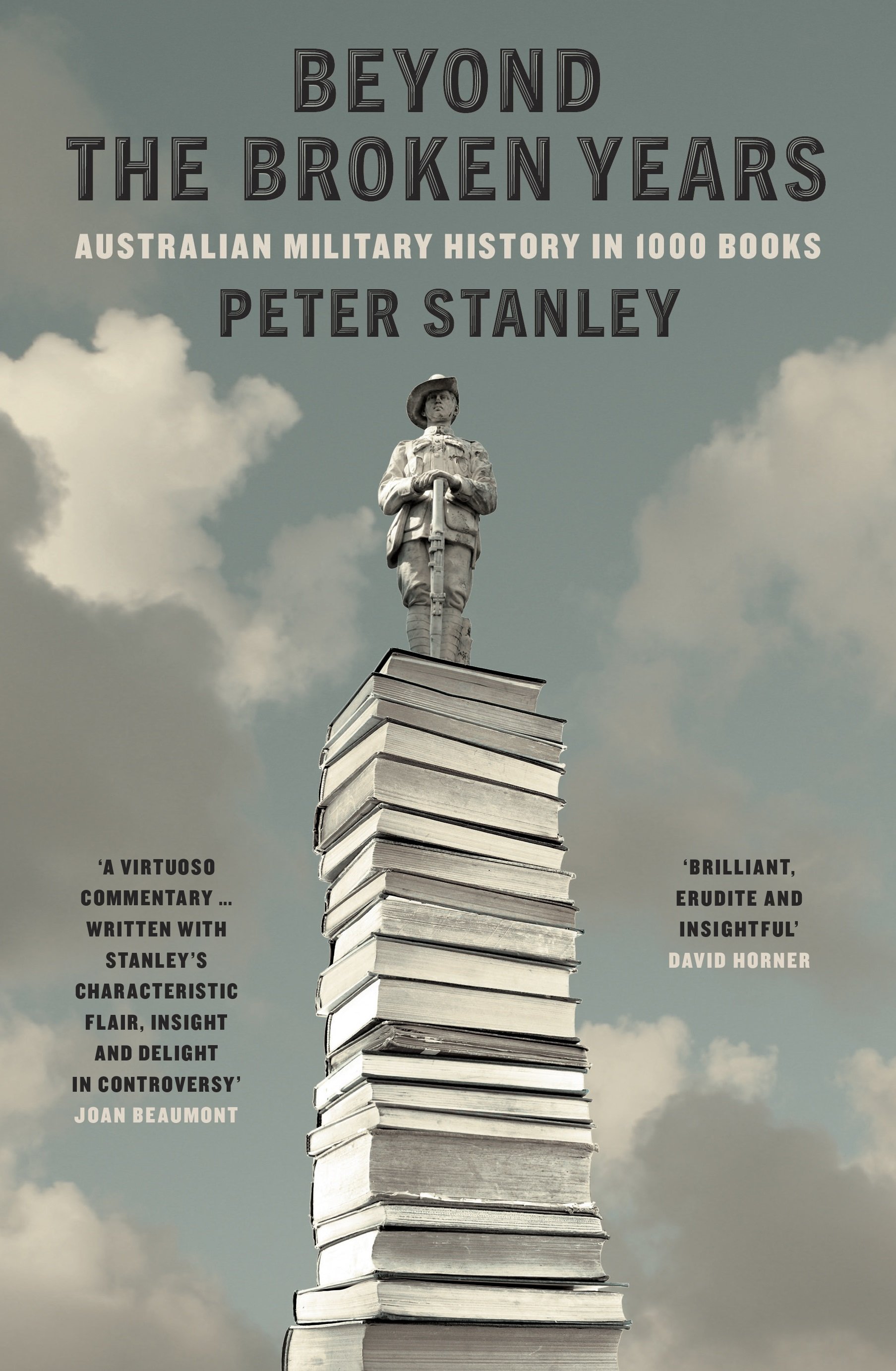

Resembling the memorials seen all over Australia, a slouch-hatted digger stands atop an obelisk, his hands resting on a service rifle. However, this obelisk is not made of granite or marble but a pile of books ascending skywards. The cover of Peter Stanley’s penetrating critique of Australian military history, Beyond the Broken Years, is a telling, if reductive, visual conceit, suggesting the instrumental role played by historians in placing the soldier on a pedestal.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Robin Gerster reviews ‘Beyond the Broken Years: Australian military history in 1000 books’ by Peter Stanley

- Book 1 Title: Beyond the Broken Years

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australian military history in 1000 books

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $39.99 pb, 243 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781761170140/beyond-the-broken-years--peter-stanley--2024--9781761170140#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

The foundational work is C.E.W. Bean’s monumental Official Historyof Australia in the War of 1914-1918, especially the first two volumes, The Story of Anzac, published in 1921 and 1924. Described by Stanley as ‘a memorial’ to the ‘virtues and heroes’ of the Australian Imperial Force, Bean’s opus inspired and intimidated scholars for decades. The ‘second Big Bang in Australian military history’, by Stanley’s reckoning, and the one which prompted the title of his book, is Bill Gammage’s The Broken Years (1974). By bringing to light the stoical suffering and quiet heroism of a thousand World War I veterans, as revealed in a treasure trove of diaries and letters hitherto hidden away in the Australian War Memorial (AWM) in Canberra, Gammage refreshed a field of study that had become unfashionable during the Vietnam years. The Broken Years ‘invigorated a generation of scholars’ and helped create an enduring boom in military history.

Stanley is eminently qualified to write a survey of military history. He is staggeringly prolific, having so far written some thirty-five works in the genre. Beyond the Broken Years is a highly readable personal and professional history, in which Stanley engages with the contexts, cross-currents, and controversies of Australian military history. He relishes writing in the first person for a change, inserting himself into the narrative as both a practitioner and an outspoken participant in public debates over historical interpretation, in his roles as Principal Historian at the AWM, then at the National Museum and UNSW Canberra.

Australian history is a ‘small world’, Stanley writes, one that is occasionally riven by internecine squabbles, ideological antagonisms, and institutional competitiveness. But the field is also a ‘fellowship’, and he pays tribute to his colleagues, even those he disagrees with – most of them, anyway. Stanley writes with plenty of needle, sharply criticising the parochialism that has infected Australian military writing, in particular of World War I. An ‘anti-British bias’ (a polite way of saying Pommy bashing) and the inclination to exaggerate the Australian endeavour are commonplace in accounts aimed at the commercial market; General John Monash is boosted as the commanding genius who ‘won the war’ on the Western Front, and Winston Churchill mocked as the blundering scapegoat for the failure of the Gallipoli campaign. Stanley’s impatience with ‘the virus of Anzackery’ reflects his leading participation in the ginger group ‘Honest History’, set up in anticipation of the welter of public commemoration that attended the 2015 centenary of the Gallipoli landings, and dedicated to countering the twisting of history to suit political ends.

C.E.W. Bean in the Western Front, 1916 (photograph by Herbret Frederick Baldwin via Wikimedia Commons)

C.E.W. Bean in the Western Front, 1916 (photograph by Herbret Frederick Baldwin via Wikimedia Commons)

Moving at a brisk, sometimes breakneck, speed, Stanley covers a broad historical terrain, and spurns sustained analysis. One theme, however, binds the discussion: ‘[t]he chasm between the more astringent academic approach and the bombastic nationalism of popular writers’. Stanley is disdainful of the so-called ‘’storians’, the term coined by the ubiquitous Peter FitzSimons, whose steady stream of bloated blockbusters, including Kokoda (2004), Tobruk (2006), and Gallipoli (2014), pursues a familiar nationalist itinerary. FitzSimons seeks to put the ‘story’ in war history, by writing it in the manner of a novelist and taking liberties with mere facts. That may be all right if you are Leo Tolstoy. FitzSimons is an obvious target of derision; that his brick-size books sell so well is a trickier issue to consider. But taking on the ‘surprisingly superficial’ research of Les Carlyon’s revered Gallipoli (2001) shows daring. For the reverberating influence of its sentimental reworking of the Gallipoli story as one of reconciliation and shared suffering between the Anzacs and the Turks – whose common enemy was ‘the arrogant and ineffectual British’ – Stanley audaciously calls Gallipoli ‘the most pernicious book in Australian military history’.

Stanley’s most acerbic comments are reserved for the former senior Liberal politician Brendan Nelson, Director of the AWM from late 2012 to 2019. Under Nelson’s highly defensive watch, Stanley writes, the institution became ‘the propaganda arm of the Defence Force’. Nelson’s ‘legacy’ has been the stupendously costly and protracted redevelopment of the Memorial complex, which has – for years – turned the site into a vast open-air version of the museum’s famous dioramas of the muddy chaos of the Western Front battlefields. (A recent visit on a dismally wet winter’s day confirmed this impression.) As a consequence, the scholarly research undertaken at the AWM’s Research Centre, formerly a valued and valuable Memorial function, has ground to a virtual halt.

Stanley is an exhaustively generous as well as selectively caustic observer. The field of Australian military history contains numerous skilled and perceptive scholars, who are given rightful recognition in this book. Stanley observes that the impact of war is experienced well beyond the battlefield, in familial suffering on the home front and in the shared trauma of returned veterans. Historians such as Joy Damousi and Michael McKernan have movingly documented its intimate and prolonged social and psychological effects, encapsulated in the title of McKernan’s This War Never Ends (2001).

On the murderous business of warfare itself, Stanley is similarly inclusive, registering the ‘intermittent but extensive series of small-scale frontier conflicts’ fought between First Nations peoples and settlers from 1788 until well into the twentieth century. Stubbornly ignored by the AWM for decades, the frontier wars caused the deaths of a number of Indigenous people that is ‘probably comparable to Australia’s deaths in the two world wars’. Stanley is rather less invested in the copiously commemorated Vietnam War, suggesting that its historical interpretation is compromised, or at least complicated, by the sheer volume of film and fiction it has generated.

Beyond the Broken Years is a salutary book aimed at stimulating reading and encouraging further work in a field sometimes viewed with suspicion. ‘Military historians are often regarded as approving of war,’ Stanley writes in one of the book’s many pungent footnotes. ‘I say that no one thinks oncologists approve of cancer.’

Although the FitzSimons factory keeps churning them out, the boom in war books has perhaps slightly abated. Has the genre been done to death? Well, no. Stanley concludes that now, in these edgy, perilous times, we need the human and political understandings that good military history can provide. And no doubt there will be more wars to come – as long as there is anyone left to write about them.

Comments powered by CComment