- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Capital ‘W’ writer

- Article Subtitle: A memoir in search of juste

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

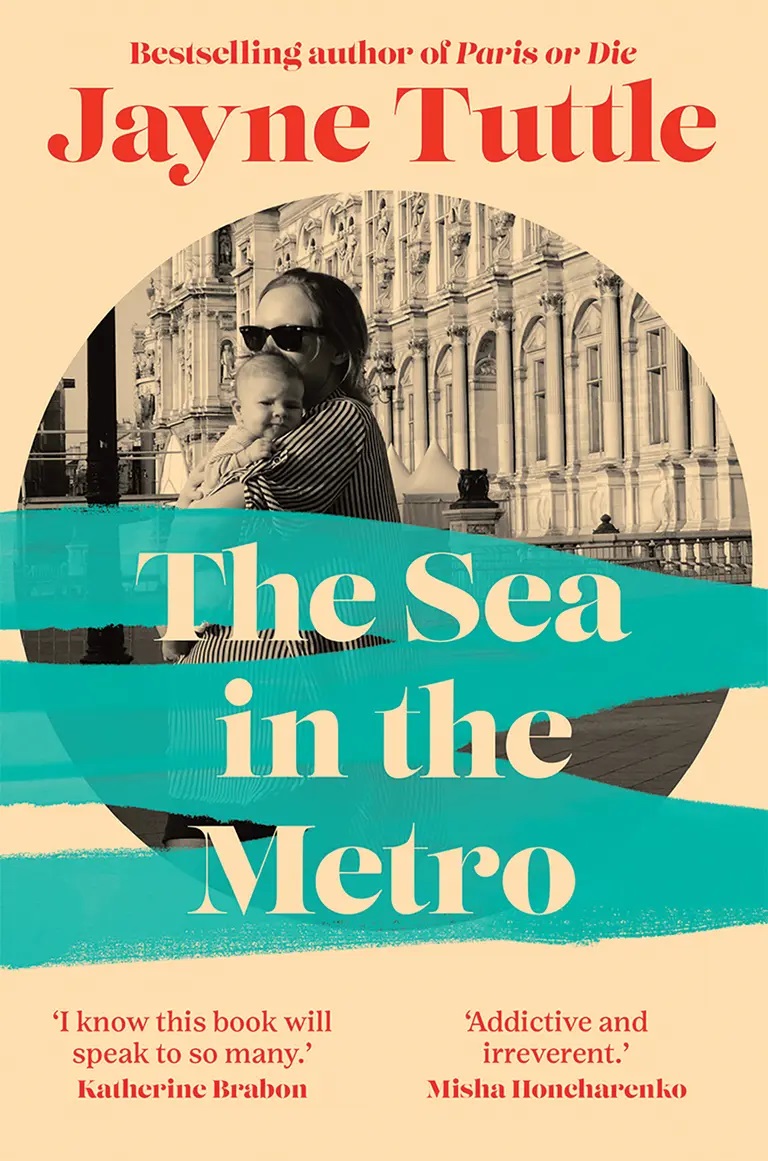

Jayne Tuttle’s The Sea in the Metro is the third book in a trilogy of memoirs about living, working, and becoming a mother in Paris. Like Paris or Die (2019) and My Sweet Guillotine (2022), Tuttle’s latest book applies a sharp scalpel to her own psyche while playing with genre. She explores the brutal realities of giving birth and raising a toddler in a foreign city, the seemingly impossible task of balancing motherhood with paid work, the joys and hardships of striving to be a capital ‘W’ writer while copywriting for cash, and what family might look like in brittle, Parisian culture. Tuttle also examines the complex ramifications of a near-death experience and a hospital birthing trauma on her ongoing physical and mental health – and intimate relationships.

- Book 1 Title: The Sea in the Metro

- Book 1 Biblio: Hardie Grant Books, $34.99 pb, 288 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781743797860/the-sea-in-the-metro--jayne-tuttle--2025--9781743797860#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

In a 2022 interview with Kate Holden in The Saturday Paper, Tuttle said that part of her is ‘driven by grief’, that she is motivated to write about things that are difficult: her mother’s death, her accident (she was nearly decapitated by a falling lift in a Parisian apartment building), and, now, pregnancy and childbirth, along with illness and trauma in the body. ‘[T]he intention’, she writes, ‘is to try to capture something; preserve it and hold it’. This has a literal meaning, too. In the book she goes into very early labour and is confined to bed for weeks, until the baby can be born safely.

Tuttle is not afraid of facing her darkest thoughts when it comes to mothering: she manages to say what many parents think but would never admit. The complexities of love, the hard realities and daily grind, are often shockingly illustrated. In one passage, Tuttle describes how she wanted to throw her daughter out the window of their apartment in a moment of frustration. These taboo thoughts are countered by the many moments of empathy and passionate observation.

The best of her writing makes manifest the power and subtlety of human contradictions. In a moment of deep ambivalence, she watches her three-year-old, who she calls ‘The Chunk’, head off in the dark on a scooter, the French school system whisking her away from 8.30 am to 4.30 pm. For Tuttle, this is hard to reconcile with the Australian childhood she experienced, as she looks at the dark circles under her daughter’s eyes in a school photograph. At school, The Chunk’s friend is not allowed to colour-in boots in just any colour: ‘Boots are brown, the teacher said. Colour them brown.’

In the Holden interview, Tuttle details her fascination with a Nan Goldin photograph of a lover masturbating, which offers a jolt of recognition and inspiration: ‘There was no delineation between herself and her work. Her work was her life.’ This sense emerges in the sheer force of Tuttle’s writing, her vivid memories, and the intimate, often ruthless, portrait we form of her: the reader feels like part of her family, sitting in the small apartment where her daughter sleeps in the walk-in wardrobe, watching her withdraw from her husband, seeing her scaffold a career of denial out of the pain and trauma she seems unable to access or cope with. Using a mastery of suspense, Tuttle structures chapters so that we begin to feel that we know more than ‘Jayne’ as we wait for the inevitable purge.

Tuttle puts ‘Jayne’ in inverted commas with her fingers when being interviewed by Linda Jaivin at the Roaring Stories Bookshop in 2022, distancing the character from herself, and it is clear that this memoir is playing with the boundaries of what non-fiction can be. In a guest post on Lee Kofman’s blog, ‘The Ecstatic Truth in Creative Nonfiction’, Tuttle says that she did not intend to write non-fiction: ‘I don’t know what it is. I don’t really want to know.’

In the memoir, she is constantly trying to find time to write ‘The Novel’, the creative act dangling over her head like the Sword of Damocles, as she writes copy for advertising clients. Her attempts at becoming what she refers to as a ‘Real Writer’ are beautifully observed, especially in the section where she places unedited notes from her writing journal, quick sketches of Paris, reminiscent of Helen Garner’s Collected Diaries, to show the raw materials she has shaped this book from; there is a wonderful sense of playfulness here.

Tuttle’s background as a performer and a writer for the theatre (she attended the École Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq in Paris and toured a stage version of her book Paris or Die in Australia and France) along with her successful copywriting career means that she is not afraid to experiment with genre and has a confident and confiding voice that immediately draws the reader in. In ‘The Ecstatic Truth’, she says that she is not so interested in factual accuracy with events and characters; she is searching for juste: ‘Juste is a word from my theatre school training; it is the feeling you get when something feels right, truthful, authentic – that spark of recognition that makes you laugh, or cry, or say “yes!”.’

It is a risk that pays off. Sea in the Metro vigorously captures the essence of Jayne and those family members and friends around her, while sparking a debate: How do you convey authenticity in memoir? The book’s evocative title gives some clues, exploring the duality of the similar sounding French terms la mère (the mother) and la mer (the sea), but also celebrating the central tenets of creativity, emotion and imagination, bodies and words that are constantly in motion. When life starts to get too intense, Tuttle’s dreams shift from an apartment on a Parisian impasse to ocean swimming in Australia. She now lives and runs a bookstore by the sea in Queenscliff. I’m looking forward to seeing where the next tide takes her.

Comments powered by CComment