- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Clancy of the overshare’

- Article Subtitle: Poetry as vibe, not polemic

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The title of Keri Glastonbury’s latest collection of poems, 51 Alterities, evokes the title of 81 Austerities (2012) by the English poet Sam Riviere. Glastonbury’s collection is, according to its author, ‘offered as a loose “antipodean” adaptation’ of 81 Austerities, a collection that was written ‘in response to the impact of austerity measures on the arts and as a provocation on poetry as a contemporary media in the internet age’. Post-internet poetry, taking on as it does the syntax and lexis of internet discourse (especially, but not wholly, that used in social media), has become a dominant style in contemporary Anglophone poetry. When 81 Austerities was reviewed by The Daily Telegraph the headline was ‘Poetry for the Facebook Age’. Such a caption now seems laughably dated, and perhaps a little naïve, suggesting something of the dangers of writing post-internet poetry. A decade is a long time in cyberspace.

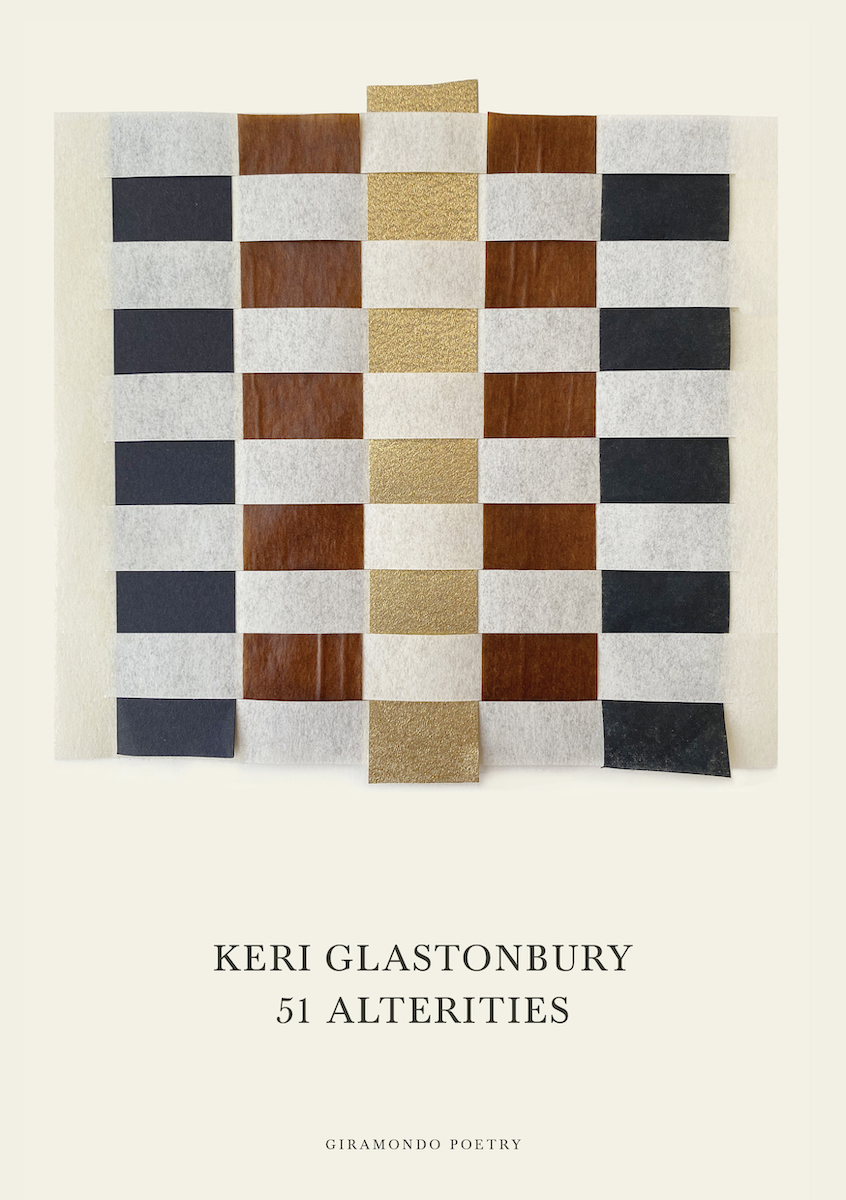

- Book 1 Title: 51 Alterities

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $27, 68 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781923106420/51-alterities--keri-glastonbury--2025--9781923106420#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Glastonbury’s ‘loose adaptation’ of Riviere’s style can be seen in the visual presentation of the poetry on the page. Each poem is shortish, free of punctuation, and usually contained in a single column. The most obviously appropriative moment in Glastonbury’s collection is the revision of Riviere’s ‘Loosely Spiritual American Poetry’, a catalogue poem that lists poetry styles which contrast with those suggested by the title ‘VS. motionless poetry of sociable professors’. Unlike Riviere’s poetry, Glastonbury’s poems are free of titles, which makes her ‘versus’ list a little more opaque, though it is full of her characteristic wit and energy, on display in lines such as ‘VS. poetry that J.K. Rowling would turf / VS. poetry that Louis C.K. would consider creepypasta’.

Anyone who has followed Rowling’s career over the last decade would get the ‘turf’ / ‘terf’ pun, but if, like me, you need to google ‘creepypasta’, a definition will be waiting for you. When it comes to the internet, the reading-writing economy is almost perfectly circular. The first readers of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922) – with its confusing storm of allusions, quotations, and references – had no app or website to refer to. Today, with all the knowledge at our fingertips, we perhaps require an even-greater allusive density in poetry. That is not to say, of course, that one needs to hunt down every apparent online reference in 51 Alterities and other collections like it. Just as Frank O’Hara – a mid-century poet of the New York School – advised, you can simply ‘go on your nerve’.

The queer, energetic spirit of O’Hara’s oeuvre has haunted generations of poets, and while Glastonbury might not be O’Hara-esque per se, her poems offer some of the same aesthetic pleasures through their use of an ironic, often humorous tone that might be termed ‘camp’. Certainly, queer identity is thematised in 51 Alterities, often comically: ‘I wasn’t doing anything / but then went and ate a whole packet / of pride Oreos from Coles / and felt celebratory and sick’. Glastonbury’s poetry is also studded with a camp-like love of word play (‘Sydney post-departum’,‘asemic coal seams’) and comedic parody. The latter is most obviously seen in this surprising renovation of Banjo Paterson’s ‘The Man from Snowy River’:

I am not an especially good

trauma counsellor

despite my Myers-Briggs ‘J’

an inviolable divine Clancy of the overshare

‘for the word had passed around’

the cult of old regret

The reference to the Myers-Briggs ‘J’ personality (preferring closure over openness) is presumably ironic, given that 51 Alterities is so consistently concerned with ambiguity and polysemy.

J stands for ‘judging’, and there are clear moments of critique in the references to ‘broligarchy’, ‘the extreme cake / of presidential pardons’, and ‘a Christian college kid mouthing off / about gender in the quiet carriage’ (the last of these surely low-hanging fruit). The poem that starts with the line ‘L’Avventura is about ennui’ quite explicitly satirises the bourgeoise, but for the most part the critique in 51 Alterities is more a vibe than obvious polemic, with poetic playfulness generally having the upper hand. This is an observation, and not a complaint; Glastonbury is too subtle a poet to bore us with opinion. However experimental the work might be, Glastonbury’s poetics are rooted in fundamentals. In particular, she is attuned to the sonic condition of poetry, which is especially obvious in her attraction to half rhyme (‘Hawkesbury’ and ‘motorway’; ‘antics’ and ‘associates’; ‘tinny’ and ‘tannoy’). Glastonbury’s playfulness is directed at the historical avant-garde, as much as Elon Musk and co. I love, for instance, the reference to ‘a lost amphitheatre / for a trucked-in piano / playing a silent John Cage sonata’. (Has anyone ever ‘performed’ Cage’s 4’33’’ as the sole piece on the program?)

For all 51 Alterities plays with internet argot and culture, a sense of real place can be felt in many of the poems, such as the one that begins ‘on the back streets of Enmore / cars wedged like bared teeth / a Cold Chisel Saturday Night (do do do etc.)’, though, as the parenthesis here again shows, a sense of shared (or googled) cultural reference is expected. As in the work of, say, the late John Forbes, the mood in Glastonbury’s collection seems conspicuously antipodean, however transnational the poet’s imagination might be.

In the final section in this work on alterity (or radical difference), the transnational becomes transhuman; the poems are studded by italicised lines that have been generated, so we are told in the endnotes, ‘using fragments from GPT-4 prompting’. I take it as the point that the style of these lines is more or less continuous with Glastonbury’s own (or ‘own’). The reference to ‘another baby reindeer / covered in snowflakes’ is pretty clever. If you don’t get it, the internet is there to help you out.

Comments powered by CComment