- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Rushed behind

- Article Subtitle: A deflated football novel

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In The Season, Helen Garner describes a photograph of Australian Football League player Charlie Curnow celebrating a goal: ‘It’s Homeric: all the ugly brutality of a raging Achilles, but also this strange and splendid beauty.’ There is a mythic image in Australian culture of the AFL player doing battle on the football oval with the strength of Hercules or the wit of Odysseus. Brandon Jack’s Pissants, his first novel, is an inversion of this mythopoeia; it is an exposé of football culture, the false pluralism of Australian masculinity, and a deranged form of identity that runs through ‘the club’. It shows the average life of a footballer at the fringes of a team list. Jack, having played for the AFL’s Sydney Swans from 2013 to 2017, has firsthand experience of the (in)famous ‘Bloods Culture’ – one built on a mantra of self-sacrifice, discipline, and unity – and this experience shows throughout the novel.

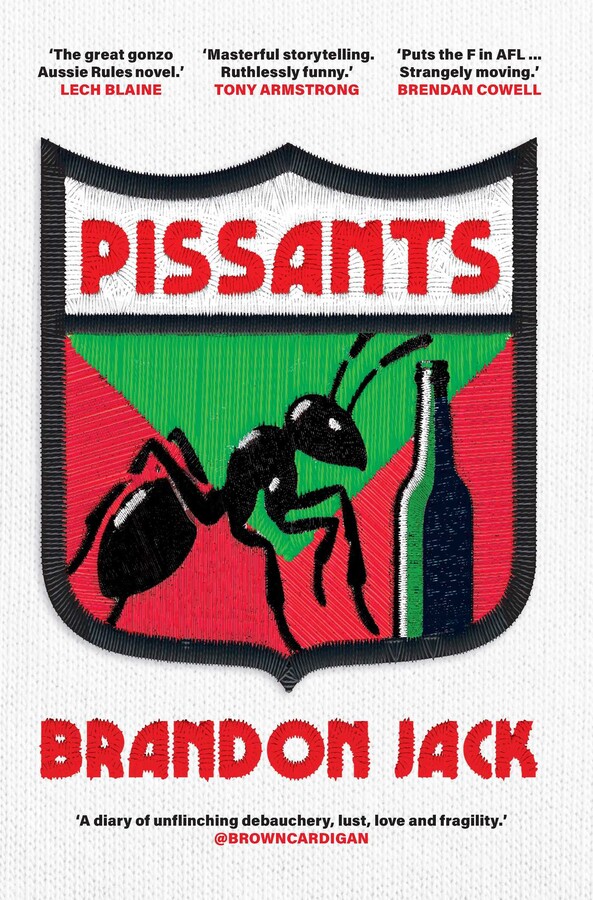

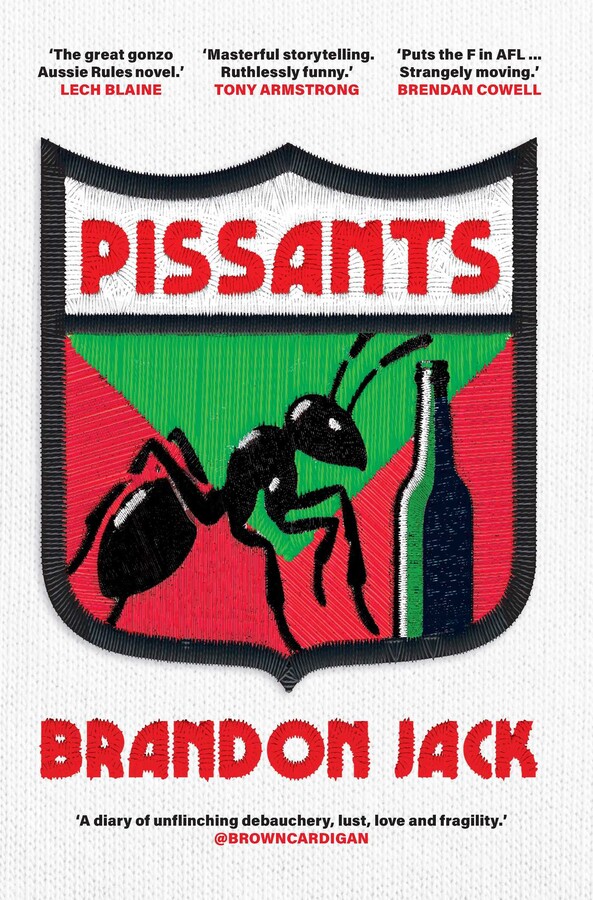

- Book 1 Title: Pissants

- Book 1 Biblio: Summit Books, $34.99 pb, 336 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781761633072/pissants--brandon-jack--2025--9781761633072#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Pissants profiles an unidentified football club. Lending to the exposé style of the novel, the name of the football club is always redacted. The reader is introduced to a smorgasbord of characters through a series of vignettes, a structure not dissimilar to the pluralistic survey of the denizens of a pub in David Ireland’s The Glass Canoe (1976). The second chapter of Pissants, ‘Nicknames’, is dedicated to cataloguing the club’s players and how they received their nicknames. These are ‘canonical stories’; the naming acts as an initiation into the club predicated on a metaphorical stripping of identity, a submission to the looming monument of ‘the club’.

There is Fangs, Stick, Mud, Gatesy, Pringles, Rimma, and many more. Although ‘Rimma’ is an intrinsically homophobic nickname, it does not make the list of ‘Nicknames That Cannot Be Ignored’, which includes ‘Shootsy’, given because its subject looks like a school shooter and ‘C.O.D.’, or ‘Cock of Death’, after that player engaged in a sexual act that caused, as a coroner described it, ‘Fatality Arising from Latex Allergy-Induce Anaphylaxis’.

This is dark and provocative content, often jarringly told through irreverent side stories. Jack includes distracting text boxes that act more like gossip columns than narrative points. One story leads to another as we follow the insular world of these reprehensible boys; they bully one another, degrade everyone and everything, all the while abusing illicit substances. A Facebook event section details (in true frat fashion) the rules of a pub golf tournament, the ‘Pissant Open’, and defines a ‘pissant’ as a guy ‘who thinks he’s the smartest prick in the room and can’t keep his mouth shut’. Throughout, we are given indulgent, repetitious details at the cost of narrative coherence. A boring, nihilistic character, Elliot – who speaks in infuriatingly declarative sentences – admits, ‘It’s all the same shit.’

Yet Jack does draw attention to the unique dialect of football clubs. Centre stage is the linguistic bouts of ‘Strine’, that violent, fluctuating vernacular found in the Division Twelve reserves or a rural RSL. Often these bouts rely on a field of insider knowledge; they are abundantly referential, filled with vulgarity and ‘piss-takes’. Shaggers begins a story like so: ‘It was a night out and he went back to theirs fuck-eyed and they got into a Matty Rowell.’

In a stream of consciousness vignette, we follow the drug-fuelled meanderings of Coach Mac at a club event: ‘Thanks, yeah, just going for a quick piss … Nah, nah, I’m ok … I don’t need a beer … thanks for asking though’. Jack’s preoccupation with language and its fragmentation reflects the novel’s disjointed narrative structure, contributing to a sense of meaninglessness. The phrases are superficial, performative uses of language that say little to nothing about the characters speaking them. While we have ten narrators, they often blur into one. Characters speaks as a football club rather than as individuals.

Perhaps it is Jack’s contention that these footballers have lost themselves and have lost meaning in their lives, but the uniformity and vulgarity of these characters make them difficult to empathise with. Because the novel’s only notable plot points are the abduction of a dachshund who subsequently dies in the pissants’ care and a tragic ending for Elliot, it risks becoming emotionally barren and nauseating in its repetition.

Pissants doesn’t have much to keep a reader engaged. The experimental parts of the novel – a story told through WhatsApp messages, a Facebook event, a bingo card – resemble gimmicks in the absence of a scaffolding narrative. Pissants is a deluge of misanthropic, meaningless venture. Sure, these are frail, broken men, but Jack doesn’t give us any reason to care about them. It’s all sound and fury.

There is also the problem of authorial intent here. Jack tries to situate the novel in a satirical, ‘piss-take’ milieu, but even the one foil character, Elliot, once removed from the club, still engages in the sexual objectification of women: ‘So, no sex then?’ he asks Emily after being told she won’t be in her room in the morning. Even as a foil he maintains the sad residues of larrikinism.

Is Pissants satire or is it indulgent? Does it contribute to the mythopoeia of the footballer by casting their homophobia and sexism as funny, or does it subvert it? Jack can’t make up his mind. Australians seem content to turn a blind eye to AFL players’ indiscretions, no matter how egregious they are, and continue to laud them as heroes. Pissants toes this line, in part revelling in toxic fraternity and at other times casting characters as tragic figures who inevitably fall. In 1961, Randolph Stow described Australia’s ‘democratic temperament, our love of sport, our depressing tolerance, and even worship, of the second-rate’. Pissants is a second-rate novel that doesn’t quite know what it wants to be.

Comments powered by CComment